Transcription

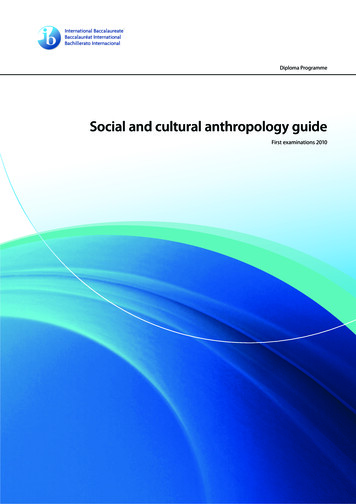

Diploma ProgrammeSocial and cultural anthropology guideFirst examinations 2010

Diploma ProgrammeSocial and cultural anthropology guideFirst examinations 2010

Diploma ProgrammeSocial and cultural anthropology guideFirst published February 2008Updated November 2010International BaccalaureatePeterson House, Malthouse Avenue, Cardiff GateCardiff, Wales GB CF23 8GLUnited KingdomPhone: 44 29 2054 7777Fax: 44 29 2054 7778Website: http://www.ibo.org International Baccalaureate Organization 2008The International Baccalaureate (IB) offers three high quality and challengingeducational programmes for a worldwide community of schools, aiming to createa better, more peaceful world.The IB is grateful for permission to reproduce and/or translate any copyrightmaterial used in this publication. Acknowledgments are included, whereappropriate, and, if notified, the IB will be pleased to rectify any errors or omissionsat the earliest opportunity.All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in aretrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the priorwritten permission of the IB, or as expressly permitted by law or by the IB’s ownrules and policy. See http://www.ibo.org/copyright.IB merchandise and publications can be purchased through the IB store athttp://store.ibo.org. General ordering queries should be directed to the sales andmarketing department in Cardiff.Phone: 44 29 2054 7746Fax: 44 29 2054 7779Email: sales@ibo.orgPrinted in the United Kingdom by Antony Rowe Ltd, Chippenham, Wiltshire3081

IB mission statementThe International Baccalaureate aims to develop inquiring, knowledgeable and caring young people who help tocreate a better and more peaceful world through intercultural understanding and respect.To this end the organization works with schools, governments and international organizations to developchallenging programmes of international education and rigorous assessment.These programmes encourage students across the world to become active, compassionate and lifelong learnerswho understand that other people, with their differences, can also be right.IB learner profileThe aim of all IB programmes is to develop internationally minded people who, recognizing their commonhumanity and shared guardianship of the planet, help to create a better and more peaceful world.IB learners strive to be:InquirersThey develop their natural curiosity. They acquire the skills necessary to conduct inquiryand research and show independence in learning. They actively enjoy learning and thislove of learning will be sustained throughout their lives.KnowledgeableThey explore concepts, ideas and issues that have local and global significance. In sodoing, they acquire in-depth knowledge and develop understanding across a broad andbalanced range of disciplines.ThinkersThey exercise initiative in applying thinking skills critically and creatively to recognizeand approach complex problems, and make reasoned, ethical decisions.CommunicatorsThey understand and express ideas and information confidently and creatively in morethan one language and in a variety of modes of communication. They work effectivelyand willingly in collaboration with others.PrincipledThey act with integrity and honesty, with a strong sense of fairness, justice and respectfor the dignity of the individual, groups and communities. They take responsibility fortheir own actions and the consequences that accompany them.Open-mindedThey understand and appreciate their own cultures and personal histories, and are opento the perspectives, values and traditions of other individuals and communities. They areaccustomed to seeking and evaluating a range of points of view, and are willing to growfrom the experience.CaringThey show empathy, compassion and respect towards the needs and feelings of others.They have a personal commitment to service, and act to make a positive difference to thelives of others and to the environment.Risk-takersThey approach unfamiliar situations and uncertainty with courage and forethought,and have the independence of spirit to explore new roles, ideas and strategies. They arebrave and articulate in defending their beliefs.BalancedThey understand the importance of intellectual, physical and emotional balance toachieve personal well-being for themselves and others.ReflectiveThey give thoughtful consideration to their own learning and experience. They are ableto assess and understand their strengths and limitations in order to support their learningand personal development. International Baccalaureate Organization 2007

ContentsIntroduction1Purpose of this document1The Diploma Programme2Nature of the subject4Aims6Assessment objectives7Assessment objectives in practice8Syllabus9Syllabus outline9Approaches to the teaching of social and cultural anthropology10Syllabus content12Assessment24Assessment in the Diploma Programme24Assessment outline—SL26Assessment outline—HL27External assessment28Internal assessment38Appendix49Glossary of command termsSocial and cultural anthropology guide49

IntroductionPurpose of this documentThis publication is intended to guide the planning, teaching and assessment of the subject in schools.Subject teachers are the primary audience, although it is expected that teachers will use the guide to informstudents and parents about the subject.This guide can be found on the subject page of the online curriculum centre (OCC) at http://occ.ibo.org, apassword-protected IB website designed to support IB teachers. It can also be purchased from the IB storeat http://store.ibo.org.Additional resourcesAdditional publications such as teacher support materials, subject reports, internal assessment guidanceand grade descriptors can also be found on the OCC. Specimen and past examination papers as well asmarkschemes can be purchased from the IB store.Teachers are encouraged to check the OCC for additional resources created or used by other teachers.Teachers can provide details of useful resources, for example: websites, books, videos, journals or teachingideas.First examinations 2010Social and cultural anthropology guide1

IntroductionThe Diploma ProgrammeThe Diploma Programme is a rigorous pre-university course of study designed for students in the 16 to 19age range. It is a broad-based two-year course that aims to encourage students to be knowledgeable andinquiring, but also caring and compassionate. There is a strong emphasis on encouraging students todevelop intercultural understanding, open-mindedness, and the attitudes necessary for them to respectand evaluate a range of points of view.The Diploma Programme hexagonThe course is presented as six academic areas enclosing a central core. It encourages the concurrentstudy of a broad range of academic areas. Students study: two modern languages (or a modern languageand a classical language); a humanities or social science subject; an experimental science; mathematics;one of the creative arts. It is this comprehensive range of subjects that makes the Diploma Programme ademanding course of study designed to prepare students effectively for university entrance. In each of theacademic areas students have flexibility in making their choices, which means they can choose subjectsthat particularly interest them and that they may wish to study further at university.group 1language A1group 2secondlanguagegroup 3individualsand societiesextended essaytheory of knowledgecreativity, action,servicegroup 4experimentalsciencesgroup 5mathematics andcomputer sciencegroup 6the arts2Social and cultural anthropology guide

The Diploma ProgrammeChoosing the right combinationStudents are required to choose one subject from each of the six academic areas, although they can choosea second subject from groups 1 to 5 instead of a group 6 subject. Normally, three subjects (and not morethan four) are taken at higher level (HL), and the others are taken at standard level (SL). The IB recommends240 teaching hours for HL subjects and 150 hours for SL. Subjects at HL are studied in greater depth andbreadth than at SL.At both levels, many skills are developed, especially those of critical thinking and analysis. At the end ofthe course, students’ abilities are measured by means of external assessment. Many subjects contain someelement of coursework assessed by teachers. The course is available for examinations in English, French andSpanish.The core of the hexagonAll Diploma Programme students participate in the three course requirements that make up the core ofthe hexagon. Reflection on all these activities is a principle that lies at the heart of the thinking behind theDiploma Programme.The theory of knowledge course encourages students to think about the nature of knowledge, to reflecton the process of learning in all the subjects they study as part of their Diploma Programme course, andto make connections across the academic areas. The extended essay, a substantial piece of writing of up to4,000 words, enables students to investigate a topic of special interest that they have chosen themselves.It also encourages them to develop the skills of independent research that will be expected at university.Creativity, action, service involves students in experiential learning through a range of artistic, sporting,physical and service activities.The IB mission statement and the IB learner profileThe Diploma Programme aims to develop in students the knowledge, skills and attitudes they will needto fulfill the aims of the IB, as expressed in the organization’s mission statement and the learner profile.Teaching and learning in the Diploma Programme represent the reality in daily practice of the organization’seducational philosophy.Social and cultural anthropology guide3

IntroductionNature of the subjectSocial and cultural anthropology is the comparative study of culture and human societies. Anthropologistsseek an understanding of humankind in all its diversity. This understanding is reached through the studyof societies and cultures and the exploration of the general principles of social and cultural life. Socialand cultural anthropology places special emphasis on comparative perspectives that challenge culturalassumptions. Many anthropologists explore problems and issues associated with the complexity of modernsocieties in local, regional and global contexts.Although social and cultural anthropology shares much of its theory with other social sciences, it is distinctin a number of ways. These distinctions include a tradition of participant observation, and an in-depthempirical study of social groups. Topics of anthropological inquiry include social change, kinship, symbolism,exchange, belief systems, ethnicity and power relations. Social and cultural anthropology examines urbanas well as rural society and modern nation states. Anthropology contributes to an understanding ofcontemporary issues such as war and conflict, the environment, poverty, injustice, inequality, and humanand cultural rights. The study of anthropology offers critical insight into the continuities as well as thedynamics of social change and the development of societies, and challenges cultural assumptions.The IB social and cultural anthropology course offers an opportunity for students to become acquaintedwith anthropological perspectives and ways of thinking, and to develop critical, reflexive knowledge. Socialand cultural anthropology contributes a distinctive approach to intercultural awareness and understanding,which embodies the essence of an IB education. Anthropology fosters the development of citizens whoare globally aware and ethically sensitive. The social and cultural anthropology course for both SL and HLstudents is designed to introduce the principles, practices and materials of the discipline.Distinction between SL and HLSL students are expected to demonstrate understanding of anthropological concepts, apply them toethnographic data, and produce sound analysis and anthropological insight into cultural behaviour. HLstudents study an additional part of the syllabus, theoretical perspectives in anthropology. HL students areexpected to incorporate a theoretical framework in their responses to paper 1 (questions 2 and 3), paper 2and paper 3 questions.HL students conduct and report a field study, whereas SL students conduct, report and critique anobservation.Prior learningNo prior study of social and cultural anthropology is expected. No particular background in terms of specificsubjects studied for national or international qualifications is expected or required of students. The specificskills required by the social and cultural anthropology course are developed during the course.4Social and cultural anthropology guide

Nature of the subjectLinks to the Middle Years ProgrammeThe concepts of Middle Years Programme (MYP) humanities can provide a useful foundation for studentswho go on to study Diploma Programme social and cultural anthropology. An understanding, developedthrough the MYP humanities course, of the concepts of time, place and space, change, systems andglobal awareness is developed further within the social and cultural anthropology course. Analytical andinvestigative skills developed in the MYP humanities course are augmented and expanded through thesocial and cultural anthropology course.Social and cultural anthropology and theory ofknowledgeGroup 3 subjects study individuals and societies. More commonly, these subjects are collectively knownas the human sciences or social sciences. In essence, group 3 subjects explore the interactions betweenhumans and their environment in time, space and place.As with other areas of knowledge, there are a variety of ways of gaining knowledge in group 3 subjects.Archival evidence, data collection, experimentation and observation, inductive and deductive reasoning,for example, can all be used to help explain patterns of behaviour and lead to knowledge claims. Studentsin group 3 subjects are required to evaluate these knowledge claims by exploring knowledge issues such asvalidity, reliability, credibility, certainty, and individual as well as cultural perspectives.The relationship between group 3 subjects and theory of knowledge is of crucial importance andfundamental to the Diploma Programme. Having followed a course of study in group 3, students should beable to reflect critically on the various ways of knowing and on the methods used in human sciences, and inso doing become “inquiring, knowledgeable and caring young people” (IB mission statement).Some of the questions that could be considered during the course are outlined below. Are the findings of the natural sciences as reliable as those of the human sciences? Can particular knowledge be used to make generalizations across time and space? To what extent can anthropology engage the public in questioning common assumptions about theworld? How do we reconcile our knowledge that we can never be objective with the assumptions of somedisciplines that objectivity is taken for granted? To what extent does society empower expert knowledge? Who validates knowledge? What is the role of power in the production of knowledge? What is the relationship between technology and the production of knowledge? Do cultural differences limit mutual understanding? Is there any necessary relationship between understanding and moral endorsement?Social and cultural anthropology guide5

IntroductionAimsGroup 3 aimsThe aims of all subjects in group 3, individuals and societies are to:1.encourage the systematic and critical study of: human experience and behaviour; physical, economicand social environments; and the history and development of social and cultural institutions2.develop in the student the capacity to identify, to analyse critically and to evaluate theories, conceptsand arguments about the nature and activities of the individual and society3.enable the student to collect, describe and analyse data used in studies of society, to test hypotheses,and to interpret complex data and source material4.promote the appreciation of the way in which learning is relevant to both the culture in which thestudent lives, and the culture of other societies5.develop an awareness in the student that human attitudes and opinions are widely diverse and that astudy of society requires an appreciation of such diversity6.enable the student to recognize that the content and methodologies of the subjects in group 3 arecontestable and that their study requires the toleration of uncertainty.Social and cultural anthropology aimsThe aims of the social and cultural anthropology course at SL and HL are to enable students to:7.explore principles of social and cultural life and characteristics of societies and cultures8.develop an awareness of historical, scientific and social contexts within which social and culturalanthropology has developed9.develop in the student a capacity to recognize preconceptions and assumptions of their own socialand cultural environments10.develop an awareness of relationships between local, regional and global processes and issues.6Social and cultural anthropology guide

IntroductionAssessment objectivesHaving followed the social and cultural anthropology course at SL or at HL, students will be expected todemonstrate the following.1.Knowledge and understandingFor example:2.–demonstrate knowledge and understanding of key terms and ideas/concepts in anthropology–demonstrate knowledge and understanding of a range of appropriately identified ethnographicmaterials–demonstrate knowledge and understanding of specified themes in social and culturalorganization–demonstrate knowledge and understanding of patterns and processes of change in society andculture–at HL only, demonstrate knowledge and understanding of theoretical perspectives inanthropology and theory related to these theoretical perspectives.Application and interpretationFor example:3.–recognize key anthropological concepts in unfamiliar anthropological materials–recognize and analyse the viewpoint of the anthropologist/position of the observer inanthropological materials–use ethnographic examples and anthropological concepts to formulate an argument–analyse anthropological materials in terms of methodological, reflexive and ethical issuesinvolved in anthropological research–at HL only, use anthropological theory or theoretical perspectives to formulate an argument.Synthesis and evaluationFor example:4.–compare and contrast characteristics of specific societies and cultures–demonstrate anthropological insight and imagination–at HL only, recognize theoretical perspectives or theories in anthropological materials and usethese to evaluate the materials.Selection and use of a variety of skills appropriate to social and cultural anthropologyFor example:–identify an appropriate context, anthropological issue or question for investigation–select and use techniques and skills, appropriate to a specific anthropological research questionor issue, to gather, present, analyse and interpret ethnographic data.Social and cultural anthropology guide7

IntroductionAssessment objectives in practiceObjectivesPaper 1Paper 2Paper 3Knowledge andunderstanding30%30%20% (HL)Application andinterpretation30%40%40% (HL)3.Synthesis and evaluation40%30%40% (HL)4.Selection and use of avariety of skills appropriateto social and 25% (SL)20% (HL)50% (SL)35% (HL)15% (HL)50%40%25% (SL)30% (HL)10%Social and cultural anthropology guide

SyllabusSyllabus outlineSpecific teaching times are not allocated to each part of the syllabus. Teachers are expected to divide theirtime across the syllabus as appropriate.Syllabus componentTeaching hoursSLHL150240Part 1: What is anthropology?1.1Core terms and ideas in anthropology1.2The construction and use of ethnographic accounts1.3Methods and data collectionPart 2: Social and cultural organization2.1Individuals, groups and society2.2Societies and cultures in contact2.3Kinship as an organizing principle2.4Political organization2.5Economic organization and the environment2.6Systems of knowledge2.7Belief systems and practices2.8Moral systemsPart 3: Observation and critique exercise (SL only)Part 4: Theoretical perspectives in anthropology (HL only)Part 5: Fieldwork (HL only)Total teaching hoursSocial and cultural anthropology guide9

SyllabusApproaches to the teaching of social and culturalanthropologyA carefully designed scheme of work will explore the relationships between topics for study and themes.Each ethnography chosen for study will cover multiple themes and topics. Social and cultural anthropologyemphasizes the interdependence of social, economic and political institutions and processes, and theirdynamic interrelations to beliefs, values and practices. While society and culture are structured, they arealso the site of conflict, challenge, and change.Teachers are encouraged to discuss and compare their views on ethnography on the OCC.Examples of possible approachesThe following two examples are intended to be suggestions for approaching these relationships. Examplesof topics and theories for study appear in bold.Example 1The study of migration as a socially embedded complex process can be approached as a topic for studyin theme 2.3 (kinship as an organizing principle), addressing the ongoing changes in gender relationsand in family and household. For example, migration may alter gender relations if women enter into themonetary sphere by working in factories. This would change their position within the economy and be linkedto economic restructuring within the household. These transformations can be examined in the context ofthe transnational system and division of labour, as listed in theme 2.5 (economic organization and theenvironment). In addition, issues related to social and group identity, listed in theme 2.1 (individuals,groups and society), may also be explored. With reference to social and group identity, processes of culturalrevitalization, sometimes linked to colonialism and post-colonialism, may also be covered, as listed intheme 2.2 (societies and cultures in contact).Students at HL will also explore ethnography on a theoretical level. An ethnographic account may addressthe issue of migration from both agency-centred and structure-centred perspectives. For example, theethnographer may draw on feminist theories that discuss women as important actors in shaping theirposition in the economic arena. Conversely, the ethnographer may also look at how national economicrestructuring forces individuals to migrate, taking a structure-centred perspective. The example of astructure-centred perspective may also link to theories that integrate world systems and politicaleconomy. In understanding these processes and relating them to theory, the ethnographer would normallytake a diachronic perspective.Example 2The study of social movements, listed in theme 2.1 (individuals, groups and society), can be approachedthrough studying the convergence of environmental and indigenous movements. For example, therestoration of a particular ecological system may provoke indigenous movements while at the same timestimulating discussion of environmental issues among local communities. The construction of social andgroup identity can be linked to theme 2.6 (systems of knowledge) and their relations with the environment.These perceptions raise issues of morality and notions of justice, as listed in theme 2.8 (moral systems), asin questions of environmental justice among segments of the population. These ways of organizing and10Social and cultural anthropology guide

Approaches to the teaching of social and cultural anthropologycomprehending social and natural environments may connect with issues of conflict and resistance,particularly the social organization of space and place in theme 2.4 (political organization). For instance,local governments may reallocate land according to the needs of developers rather than those of indigenouspeoples. This might create conflict between indigenous peoples and local authorities and also evoke variousforms of resistance. Furthermore, development policies and the role of applied anthropology can beexplored in relation to these themes, as listed in theme 2.5 (economic organization and the environment).Students at HL may understand an account of social movements as being written from a conflictcentred perspective, as the ethnographer may choose to emphasize the competing interests of variousgroups. Furthermore, the ethnographer may take a structure-centred perspective that would emphasizeinstitutional factors in the allocation of land resources. Teachers may highlight the materialist perspective ofthe ethnographer who emphasizes land tenure and economic change as key to understanding the dynamicsof the given society. In this context the materialist perspective may be drawn out with political economyand environmental anthropology. Additionally, the ethnographer may draw from symbolic theory toshow how differing world views contribute to the development and changing nature of movements.Social and cultural anthropology guide11

SyllabusSyllabus contentPart 1: What is anthropology? (SL and HL)All students of social and cultural anthropology should be familiar with the set of core terms, the methodsused by anthropologists and issues associated with the construction of ethnographic accounts. The teachingof part 1 should be integrated with the study of ethnography throughout the entire course. Part 1 will helpstudents to better understand part 2. Students should have an understanding of how the terms, methodsand different approaches to the construction of ethnographic accounts are connected with the historicalcontext of the discipline.1.1 Core terms and ideas in anthropologyWhile reading anthropological material, students will encounter core terms and ideas. These terms andideas are used to describe and analyse individuals and groups in their social contexts. Students should betaught that these terms have theoretical and historical contexts. The meanings of these terms change overtime, and new terms and ideas are constantly emerging. The following list of core terms and ideas is notexhaustive. They should not be presented and studied as isolated entities.AgencyAgency is the capacity of human beings to act in meaningful ways that affect their own lives and those ofothers. Agency may be constrained by class, gender, religion and other social and cultural factors. This termimplies that individuals have the capacity to create, change and influence events.CommunityCommunity is one of the oldest concepts used in anthropological studies. Traditionally, it referred to ageographically bounded group of people in face-to-face contact, with a shared system of beliefs andnorms operating as a socially functioning whole. Communities existed within a common social structureand government. More recently, communities have also been defined as interest groups accessed throughspace, as in “Internet communities” or “communities of taste”. With the advent of globalism and globalstudies that often question the stability of territories, space and place, community is now a highly contestedconcept.ComparativeAnthropologists strive to capture the diversity of social action and its predictability by focusing on the wayin which particular aspects of society and culture are organized similarly and differently across groups.While social action is frequently innovative, there are limits to its diversity, and patterns identified in onegroup resemble patterns identified in another.Cultural relativismFor anthropologists, cultural relativism is a methodological principle that emphasizes the importance ofsearching for meaning within the local context. Non-anthropologists often interpret cultural relativism asa moral doctrine, which asserts that the practices of one society cannot be judged according to the moralprecepts and evaluative criteria of another society. In its extreme form, this version of cultural relativism canlead to a non-analytical position that is contrary to the critical commitments of the discipline.12Social and cultural anthropology guide

Syllabus contentFor anthropologists, cultural relativism attempts to recognize and address the problem of ethnocentrism.Ethnocentrism is the tendency to evaluate the practices of others in terms of one’s own criteria. Generally,ethnocentrism has the effect of giving greater worth to the social or cultural context of the evaluator thanto the context being evaluated, and hinders understanding across social boundaries.CultureCulture refers to organized systems of symbols, ideas, explanations, beliefs and material production thathumans create and manipulate in the course of their daily lives. Culture includes the customs by whichhumans organize their physical world and maintain their social structure. While many anthropologistshave thought of culture simply as shared systems of experiences and meanings, more recent formulationsof the concept recognize that culture may be the subject of disagreement and conflict within and amongsocieties.Human awareness of culture may be only partly conscious, and humans learn to manipulate culturalcategories throughout their lives. It is this ability to manipulate and transform culture that distinguisheshumans from other animals.EthnographicAnthropology places considerable emphasis on its empirical foundation based on a direct engagementwith particular people and their social and cultural context. Ethnographic materials are usually gatheredthrough participant observation.Ethnographically grounded anthropology can be contrasted with 19th century “armchair” anthropologyconducted by scholars with no first-hand acquaintance with the societies they analysed, and with “commonsense” or journalistic accounts of a particular soc

4 Social and cultural anthropology guide Social and cultural anthropology is the comparative study of culture and human societies. Anthropologists seek an understanding of humankind in all its diversity. This understanding is reached through the study of societies and cultures and the exploration of the gener