Transcription

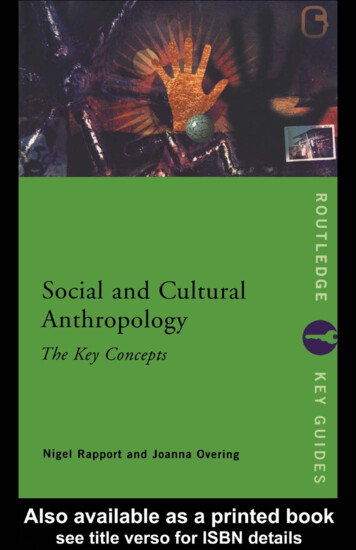

SOCIAL AND CULTURALANTHROPOLOGYThe Key ConceptsSocial and Cultural Anthropology: The Key Concepts is the ideal guide to thisdiscipline, defining and discussing its central terms with clarity andauthority. Among the concepts explored are: Cybernetics Ecriture Feminine Gossip Human Rights Alterity Stereotypes Kinship Thick Description ViolenceEach entry is accompanied by specific cross-referencing and there is anextensive index and bibliography. Providing both historical commentaryand future-oriented debate Social and Cultural Anthropology: The KeyConcepts is a superb reference resource for anyone studying or teachinganthropology.Nigel Rapport is Professor of Anthropological and PhilosophicalStudies at the University of St Andrews and the author of numerousbooks on anthropology, including Transcendent Individual: Essays Toward aLiterary and Liberal Anthropology (1997) and, with Anthony P.Cohen,Questions of Consciousness (1995), both published by Routledge. JoannaOvering is Professor and Chair of Social Anthropology, also at theUniversity of St Andrews. She is the author of many publications onAmazonia and on anthropological theory. She was editor of the volumeReason and Morality (Routledge, 1985).

ROUTLEDGE KEY GUIDESAncient History: Key Themes and ApproachesNeville MorleyEastern Philosophy: Key ReadingsOliver LeamanFifty Contemporary Choreographersedited by Martha BremserFifty Eastern ThinkersDiané Collinson, Kathryn Plant and Robert WilkinsonFifty Key Contemporary ThinkersJohn LechteFifty Key Thinkers in International RelationsMartin GriffithsFifty Major EconomistsSteven PressmanFifty Major PhilosophersDiané CollinsonKey Concepts in Communication and Cultural Studies (second edition)Tim O’Sullivan, John Hartley, Danny Saunders, Martin Montgomeryand John FiskeKey Concepts in Cultural Theoryedited by Andrew Edgar and Peter SedgwickKey Concepts in Eastern PhilosophyOliver LeamanKey Concepts in Language and LinguisticsR.L.TraskKey Concepts in the Philosophy of EducationChristopher Winch and John GingellKey Concepts in Popular MusicRoy ShukerKey Concepts in Post-Colonial StudiesBill Ashcroft, Gareth Griffiths and Helen TiffinCinema Studies: The Key Concepts (2nd edition)Susan HaywardSocial and Cultural Anthropology: The Key ConceptsNigel Rapport and Joanna Overing

SOCIAL ANDCULTURALANTHROPOLOGYThe Key ConceptsNigel Rapport and Joanna OveringLondon and New York

First published 2000 by Routledge11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EESimultaneously published in the USA and Canadaby Routledge29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor and Francis GroupThis edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2003. 2000 Nigel Rapport and Joanna OveringAll rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted orreproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical,or other means, now known or hereafter invented, includingphotocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrievalsystem, without permission in writing from the publishers.British Library Cataloguing in Publication DataA catalogue record for this book is available from the British LibraryLibrary of Congress Cataloging in Publication Datahas been applied forISBN 0-203-45113-9 Master e-book ISBNISBN 0-203-75937-0 (Adobe eReader Format)ISBN 0-415-18155-0 (hbk)ISBN 0-415-18156-9 (pbk)

CONTENTSAbout the bookList of conceptsviixiKEY CONCEPTS1BibliographyIndex409445v

ABOUT THE BOOKThis is a book of some sixty essays each of which deals with animportant term in the toolbox of contemporary anthropological studies.The aim is to provide a concise repository of explanatory statementscover ing a number of the major concepts that professionalanthropologists might use.‘Explanation’ here includes argumentation concerning the diversityof ways in which anthropologists have understood the key concepts oftheir discipline and the way these have changed over time and might beexpected to change in future. The volume is both overview and polemic,intended as a study guide as well as a research tool for original writing.The ‘cultural anthropological’ tradition originating in North Americaand the ‘social anthropological’ tradition of Europe are combined in thebook, reflecting the growing similarity of what is taught in universitycourses around the world.Key Concepts would write anthropology into a changing environmentof academic disciplines—their changing interrelations, methodologiesand epistemologies—in the light of the current (‘post-modern’,‘reflexive’) blurring of generic divisions and challenge to establishedverities. The volume draws on a range of disciplinary sources (includingphilosophy, psychology, sociology, cultural studies, literary criticism andlinguistics), so situating anthropology within a broadly conceived notionof the humanities.***A book of key anthropological concepts is something of a departure.There are a number of introductions to anthropology (Social Anthropology(Leach 1982), Other Cultures (Beattie 1964)), also dictionaries (TheDictionary of Anthropology (Barfield 1997), Macmillan Dictionary ofAnthropology (Seymour-Smith 1986)), encyclopaedias (Encyclopedia ofvii

ABOUT THE BOOKSocial and Cultural Anthropology (Barnard and Spencer 1996), Encyclopediaof Cultural Anthropology (Levinson and Ember 1996)), and a companion(Ingold 1994a); but there have not been many attempts to distil‘anthropological wisdom’, theoretical, methodological, analytical andethnographic, by way of key concepts.Of the two most comparable volumes, Robert Winthrop’s Dictionaryof Concepts in Cultural Anthropology (1991), and South African Keywordsedited by Emile Boonzaier and John Sharp (1988), Winthrop’s ratherparticular emphasis on ‘cultural anthropology’ as the description andinterpretation of ‘culturally patterned thought and behavior’ (1991:ix)means that there are few overlaps—‘community’, ‘interpretation’,‘network’, ‘urbanism’, ‘world-view’,—between the eighty concepts hehighlights and those selected here. Boonzaier and Sharp, meanwhile,analyse thirteen key words which they take to be instrumental in theconstruction, representation, objectification and interpretation of SouthAfrican apartheid, both by anthropologists and by politicians. While lessethnographically focused than Boonzaier and Sharp’s volume, thepresent book attempts likewise to look askance at the ‘culture andsociety’ of anthropology as an academic discipline and relate itsconceptual tools to wider philosophical and folk discourses.It echoes Boonzaier and Sharp too in claiming kinship with, anddrawing inspiration from, an original project of the Marxian critic andtheorist of culture, Raymond Williams. In 1976, Williams produced abook of Keywords in which he attempted to isolate certain significantlandmarks in Western social and cultural discourse. The approach hadbeen made famous in Germany, since the Second World War, under thetitle, Begriffsgeschichte, or ‘conceptual history’; shifts and discontinuities inconceptual for mation, it was argued, were an index of widersociocultural change as well as being instrumental in the shaping of suchchange. Through an assemblage of ‘keywords’, Williams explained(1983a:15), he sought to delineate and detail a complex and broadlandscape of the Western imagination. Here were 131 words, hesuggested, which forced themselves on his attention because of theirgeneral sociocultural import: their indicativeness of certain abidingvalues or forms of thought, and their connection to certain fundamentalactivities.The key concepts signalled in this book are to be regarded in acomparable way: they are discursive nodes from which a broader,interconnected landscape of anthropological work and understandingshould become apparent. The dictionary defines ‘concepts’ as ‘thingsformed through the power of the mind’, also ‘general notions, fancies,thoughts and plans’ (Chambers 1966). More technically, one might wish toviii

ABOUT THE BOOKidentify by ‘concepts’ the specific things that human beings think about,the meaning(s) of those things at particular moments, and the relationsbetween those things and various other things in a classificatory array (cf.McInnis 1991:vii). Each concept-entry in this book sets out to define anaspect of anthropological thought, therefore, to describe something of therange of a concepts meaning-in-use, and to offer pointers towards otherentries with which the concept can be seen to connect.Raymond Williams’s espying of a landscape of Western socioculturaldiscourse was an inevitably partial exercise; also, partisan, subjective,programmatic and open-ended. At the same time as it claimed to espy italso created a landscape; seeking to compass a vocabulary it succeeded,above all, in generating further discussion. The enterprise of Keywords wasto provide an argument more than an encyclopaedic lexicon. This bookwould offer no more and no less than that. It is imbued with theperspective of its authors; it is the landscape of anthropology as they seeand interpret it. Indeed, the authors would argue that the notion of anacademic discipline (as with any other institution) whose workings anduse are intrinsically perspectival, contingent, subjective and situationalmatters, and in that sense anti-disciplinary, is in itself an inherently‘anthropological’ notion.***The key concepts adumbrated by this book figure as some sixty essays, asmentioned. These range in length from approximately 500 words to5000, as the significance of the concepts varies and as they give on todiscussions of variable complexity. The concepts also cover a range oftypes: ontological (‘Agent and Agency’, ‘Consciousness’, ‘Gender’),epistemological (‘Cyber netics’, ‘Kinship’, ‘World-View’),methodological (‘Culture’, ‘Methodological Individualism and Holism’,‘Literariness’), theoretical (‘Community’, ‘The Unhomely’, ‘Urbanism’),and ethnographic (‘Home and Homelessness’, ‘Myth’, ‘Tourism’).The essay format is intended to give sufficient space for the history ofusage of the concept to be addressed and the argumentation surroundingit, also the way that conceptual meanings change over time andaccording to author and context. Besides the labelled concept-entries,however, there is a detailed Index to this book which can be used toinquire more immediately of precise features in the discipline’sdiscursive landscape. Finally, there is an extensive Bibliography of sourceswhich directs the reader to further, specialized readings.***ix

ABOUT THE BOOKAmid the diversity and range of the volume, its partiality and openendedness, it is intended that its dual authorship will tend towards aconsistency of ethos and continuity of voice in the whole—at the least,towards a consistency and continuity of narrative tension.A number of other voices have nonetheless ably assisted the authorsin composing their text. For their support and advice the authors wouldlike very much to thank Anthony Cohen, Andrew Dawson, Alan Passes,Marnio Teixeira-Pinto and Jonathan Skinner; Elizabeth Munro andNapier Russell; also their editors at Routledge, Roger Thorp and HywelEvans, and copy editor Michael Fitch.NJR and JOSt Andrews 1999x

LIST OF CONCEPTSAgent and ionCodeCognitionCommon onCultureCyberneticsDialogics and AnalogicsDiscourseEcriture FeminineEthnomethodologyForm and ContentGenderGossipHome and HomelessnessHuman nInterpretationIronyKinshipxi

LIST OF CONCEPTSLiminalityLiterarinessMethodological EclecticismMethodological Individualism and HolismMoments of dernismQualitative and Quantitative MethodologiesReadingThe Rural IdyllScienceSituation and ContextSocietyStereotypesThick DescriptionTourismTransactionThe -ViewWritingxii

AGENT AND AGENCYAGENT AND AGENCYThe concepts of agent and agency, perhaps related most closely to that ofpower, are usually deployed in debates over the relationship betweenindividuals and social structure. They also pertain, however, to the natureof individual consciousness, its ability to constitute and reconstitute itself,and, ultimately, the extent of its freedom from exterior determination.Agency and structureAgents act, and agency is the capability, the power, to be the source andoriginator of acts; agents are the subjects of action. Weber suggested thatacts be distinguished from mere (animal) behaviour on the basis of actsbeing seen to entail a number of features of human rationality:consciousness, reflection, intention, purpose and meaning. He felt thatsocial science should be an interpretive study of the meanings of humanaction and the choices behind them. G.H.Mead sought to clarify theWeberian notion of meaning, and its social-scientific understanding(Verstehung), by differentiating acts into: impulses, definitions of situations,and consummations.On a Durkheimian view, however, what was crucial for anappreciation of human action were the conditions under which, andmeans by which, it took place; also the norms in terms of whichchoices between acts were guided. Over and against action, therefore,were certain structures which implied constraint, even coercion, andwhich existed and endured over and above the actions of particularindividuals, lending to individuals’ acts a certain social and culturalregularity. What social science should study, therefore, was how suchformal structures were created and how precisely they determinedindividual behaviour. To the extent that ‘agency’ existed, in short, itwas a quality which derived from, and resided in, certain collectiverepresentations: in the social fact of a conscience collective; only in theirpre-socialized, animal nature (a pathological state within a sociocultural milieu) were individuals able to initiate action which was notpredetermined in this way.Much of the literature on agency since the time of Weber andDurkheim has sought to resolve these differences, and explore the limitson individual capacities to act independently of structural constraints.Despite attempts at compromise, moreover, the division does not provean easy one to overcome. Either, in more individualistic or liberal vein,one argues that structures are an abstraction which individuals createandwhich cannot be said to determine, willy-nilly, the action of their1

AGENT AND AGENCYmakers. Or else, in more collectivist and communitarian vein, one arguesthat structures are in fact sui generis and determine the very nature ofindividual consciousness and character: so that individuals’ ‘acts’ aremerely the manifestation of an institutional reality, and a set of structuralrelations.Numerous claims to compromise have been put forward,nonetheless, most famously by Parsons (the theory of social action andpattern variables, e.g. 1977), by Berger and Luckmann (the theory ofthe social construction of reality, 1966), by Giddens (structurationtheory, 1984), and by Bourdieu (the theory of practice and the habitus,1977). In each case, however, the theorist can be seen to end byprivileging one or other of the above options; the compromise is hardto sustain. Hence, a division between social structure and individualagency is collapsed in favour of either a liberal or a communitarianworld-view—and more usually (certainly regarding the aboveclaimants) the latter (cf. Rapport 1990).For example, for Bourdieu, to escape from vulgarly mechanisticmodels of socio-cultural determinism is not to deny the objectivityof prior conditions and means of action and so reduce acts’ meaningand or ig in to the conscious intentions and deliberations ofindividuals. What is called for is a more subtle approach toconsciousness where, in place of a simple binary distinction betweenthe conscious and the unconscious, one recognizes a continuum. Onealso recognizes that the greater part of human experience liesbetween the two poles, and may be called ‘the domain of habit’: mostconsciousness is ‘habitual’. It is here that socialization and earlylearning put down their deepest roots; it is here that culture becomesencoded on the individual body, and the body becomes a mnemonicdevice for the communication and expression of cultural codes (ofdress and gender; of propr iety and nor malcy; of control anddomination). Competency in social interaction is also to be found inthe habitual domain between the two poles: individuals act properlyby not thinking about it. In short, the wide provenance of habit inhuman behaviour is a conduit for the potency of processes ofexterior determination and institutionalization. Objective socialstructures produce the ‘habitus’: a system of durable, transposabledispositions which function as the generative basis of structured,objectively unified, social practices. Such dispositions and practicesmay together be glossed as ‘culture’, an acquired system of habitualbehaviour which generates (determines) individuals’ schemes ofaction. In short, social structures produce culture which, in turn,generates practices which, finally, reproduce social structures.2

AGENT AND AGENCYIn this way, the ‘compromise’ which Bourdieu provides ends upbeing a structurally causal model based on reified abstractions andmaterialist determinations. While claiming to transcend the dualismbetween structure and agency Bourdieu remains firmly rooted in acommunitarian objectivism. While claiming to reject deterministic logicwhich eschews individual action, what there is of the latter (theintentionless convention of regulated improvisation) is merely a mediumand expression of social-structural replication; what (habitual)subjectivity is allowed for in Bourdieu‘s portrayal is heavilyoverdetermined by social process. Agency is reduced to a seeminglypassive power of reacting (habitually) to social-structural prerequisites (cf.Jenkins 1992).Creativity and imaginationWhat social science often effects when faced with irresolvableopposition is a change in the terms of the debate. Thus, fresh purchase isgained on the relationship between social structure and individualagency when ‘creativity’ is introduced: the creativity of an individualagent in relation to the structures of a socio-cultural milieu.Extrapolating from processes of fission and fusion (of‘schismogenesis’) among the New Guinean Iatmul, Bateson concludedthat each human individual should be conceived of as an ‘energy source’(1972:126). For here was something fuelled by its own processes(metabolic, cognitive and other) rather than by external stimuli, andwhich was capable of, and prone to, engagement in its own acts.Furthermore, this energy then imposed itself on the world, energizingcertain events, causing certain relations and giving rise to an interactionbetween things organic and inorganic, which were then perceived to be‘orderly’ or ‘disorderly’.Human individuals were active participants in the world, in short.Indeed, inasmuch as their energy determined the nature of certainrelations and objects in the world, individuals could be said to becreators of worlds. For what could be understood by ‘order’ or ‘disorder’were certain relationships between certain objects which individualscame to see as normal and normative or as abnormal and pathological;here were some from an infinite number of possible permutations ofobjects and relations in the world, whose classification and evaluationwere dependent on the eye of the perceiver. But there was nothingnecessary, objective or absolute about either designation; ‘disorder’ and‘order’ were statements as construed by individual, purposive, perceivingentities and determined by individuals’ states of mind. Between these3

AGENT AND AGENCYlatter there was great diversity, however, both at any one time andplaceand between times and places. What was random or chaotic for oneperceiver may be orderly and informational for another, which in turngave rise to the disputational, conflictual and ever-changing nature ofsocial relations and cultural arrangements.Bateson’s commentary was widely appreciated, taken on, for instance,by psychiatrist R.D.Laing, and his definition of a person as ‘an origin ofactions’, and ‘a centre of orientation of the objective universe’ (1968:20).Strong echoes of Bateson also occur in Edmund Leach‘s alluding to theimaginative operations of the individual human mind and its ‘poeticism’:its untrammelled and unpredictable and non-rule-bound nature(1976a:5). ‘You are your creativity’, Leach could conclude (1976b).It is useful also to broaden the focus and remark upon theconvergences between Bateson‘s ethnographic conclusions andExistentialism’s philosophic ones. As Sartre famously put it, ‘beingprecedes essence’: each human being makes himself what he is,creating, and recreating continually, himself and his world. Of course,individuals are born into certain socio-cultural situations, into certainhistorical conditions, but they are responsible for the sense they(continue to) make out of them: the meaning they grant them, the waythey evaluate and act towards them. Indeed, individuals are for ever inthe process of remaking their meanings, senses, evaluations and actions;they negate the essence of their own creations and create again. Theymight seem to be surrounded by the ‘actual facts’ of an objectivehistorico-socio-cultural present, but they can nonetheless transcend thelatters’ brutishness, and hence surpass a mere being-in-the-midst-ofthings by attaining the continuous possibility of imagined meanings.Between the (structurally) given and what this becomes in anindividual life there is a perennial (and unique) interplay; individualexperience cannot be reduced to objective determinants (cf. Kearney1988:225–41).Imagination is the key in this depiction: the key resource inconsciousness, the key to human being. Imagination is an activity inwhich human individuals are always engaged; and it is through theirimagination that individuals create and recreate the essence of theirbeing, making themselves what they were, are and will become. As Sartreput it, imagination has a ‘surpassing and nullifying power’ which enablesindividuals to escape being ‘swallowed up in the existent’; it frees themfrom given reality, and allows them to be other than how they mightseem to be made (1972:273). Because of imagination, human life has anemergent quality, characterized by a going-beyond: going-beyond agiven situation, a set of circumstances, a status quo, going-beyond the4

AGENT AND AGENCYconditions that produced it. Because of imagination,the human world ispossessed of an intrinsically dynamic order which individuals, possessedof self-consciousness, are continually in the process of forming anddesigning. Because they can imagine, human beings are transcendentallyfree; imagination grants individuals that margin of freedom outsideconformity which ‘gives life its savor and its endless possibilities foradvance’ (Riesman 1954:38).Imagination issues forth into the world in the form of an ideally‘gratuitous’ act, gratuitous inasmuch as it is seemingly uncalled for interms of existent reality: unjustifiable, ‘without reason, ground or proof(Chambers Dictionary). For here is an act which surpasses rather thanmerely conserves the givenness in which it arises, which transcends theapparent realities of convention, which seems to resist the traditionalconstraints by which life is being lived. The gratuitous act appears tocome from nowhere and pertain to nothing, something more or lessmeaningless in terms of the sense-making procedures which arecurrently instituted and legitimated; what is gratuitous is beyond debtand guilt, beyond good and evil.Finally, then, it is the gratuitousness of the creative act of humanimagination which makes it inherently conflictual; for, between theimagination and what is currently and conventionally lived there will bea constant tension. The indeterminacy of the relationship betweenindividual experience and objective forms of life—the dialecticalirreducibility of conventional socio-cultural conceptualizations on theone side and conscious individual imaginings on the other—means thatthe becoming of new meanings will always outstrip the present being ofsocio-cultural conditions. For, while what is currently lived is itself theissue of past imaginative acts of world-creation, and dependent oncontinuing individual practice for its continuing institutionality,inevitably, present imaginative acts will be moving to new possiblefutures; in the process of creating a new world, existing worlds areinexorably appropriated, reshaped and reformed. Or, to turn this around,the continuity of the conventional is an achievement and a consciousdecision (not a mindless conformity) which must be continually workedfor—consensually agreed upon or else forcibly imposed.Anthropology and creativityThe essence of being human, Leach argued, is to resent the dominationof others and the dominion of present structures (1977:19–20). Hence,all human beings are ‘criminals by instinct’, predisposed to set theircreativity against cur rent system, intent on defying and5

AGENT AND AGENCYreinterpretingcustom. Indeed, it is the rule-breaking of ‘inspiredindividuals’ which leads to new social formations and on which culturalvitality depends. Nevertheless, the hostility of creativity to systems as are,means that its exponents are likely to be initially categorized andlabelled as criminal or insane—even if their ultimate victoriousoverturning of those systems’ conservative morality precipitates theirredefining as heroic, prophetic or divine.Narrowing the discussion of the existential imagination to morestrictly anthropological work once more, Leach’s is a good place to start.That of Victor Turner provides another (1974,1982a). Abstracting fromthe ritual practices undertaken in the liminal period of Ndembu rites ofpassage, Turner could understand the entire symbolic creation of humanworlds as turning on the relation between the formal fixities of socialstructure and the fluid creativity of liminoidal ‘communitas’. Drawing onSartre’s dialectic between ‘freedom and inertia’ (as Leach drew onCamus’s ‘essential rebellion’), Turner theorized that society could beregarded as a process in which the two ‘antagonistic principles’, the‘primordial modalities’, of structure and creativity could be seeninteracting, alternating, in different fashions and proportions in differentplaces and times. Creativity appeared dangerous—anarchic, anomic,polluting—to those in positions of authority, administration orarbitration within existing structures, and so prescriptions andprohibitions attempted precisely to demarcate proper and possiblebehavioural expressions. But, notwithstanding, ideologies of otherness (aswell as spontaneous manifestations of otherness) would erupt from theinterstices between structures and usher in opposed and originalbehavioural proprieties for living outside society (ritually if notnormatively) or else refashioning in its image society as such.Or again, in his Someone, No One. An Essay on Individuality (1979),Kenelm Burridge formulated a theoretical model similarly based on aprocessual relationship between social structure and individual creativity.If ‘persons’ were understood to be products of material (socio-historicocultural) conditions, and lived within the potential of given concepts—feeding on and fattened by them, killing for and being killed by them—so individuals existed in spite of such concepts and conditions, seekingthe disorderly and the new and refusing to surrender to things as theywere or as traditional intellectualizations and bureaucratizations wishedthem to be. For to ‘become’ an individual was to abandon selfrealization through the fulfilment of normative social relations, and toconcentrate one’s individual intuitions, perceptions and behaviourinstead on the dialectical relationship ‘between what is and what mightbe’ (1979:76).6

AGENT AND AGENCYMoreover, ‘individuality’ might be how one identified the practiceof moving to the status of being individual, Burridge expounded,something of which each ‘organism’ was capable. What individualitydid, in effect, was to transform the person, a social someone, into asocial no-one—an ‘eccentric’ at least. However, if others were willingto accept for themselves—as new intellectualizations, a new morality—the conceptual creations of the ‘eccentric’ individual, then the movefrom someone to no-one culminated in their becoming a new socialsomeone, a new ‘person’. That is, persons were the endpoint of ‘heroic’individuals, individuals who had persuaded (or been mimicked by)others into also realizing new social conditions, rules, statuses, roles; forhere, individuality dissolved into a new social identity. Indeed,Burridge concluded, the cycle of: ‘someone’ to ‘no-one’ to ‘someone’,was inevitable, and individuality a ‘thematic fact of culture’ (1979:116).Here was the universal instrument of the moral variation, thedisruption, the renewal and the innovation which were essential tohuman survival, whether for hunters-and-gatherers, pastoralists,subsistence agriculturalists, peasants, village people, townsfolk or citydwellers. Different material conditions may eventuate in situationswhich variously allowed, encouraged or inhibited moves to theindividual and moments of creative apperception, but over and abovethis, individuals’ creativity meant that they continually created theconditions and situations which afforded them their opportunity.In sum, there were ever individuals who were determined to be‘singletons’: to interact with others and with established rationalizationsin non-predefined ways, to escape from the burden of given culturalprescriptions and discriminations, and so usher in the unstructured andas yet unknown. Whether courtesy of (Aborigine) Men of High Degree,(Cuna) shamans,

books on anthropology, including Transcendent Individual: Essays Toward a Literary and Liberal Anthropology (1997) and, with Anthony P.Cohen, Questions of Consciousness (1995), both published by Routledge. Joanna Overing is Professor and Chair of Social Anthropology, also at the University