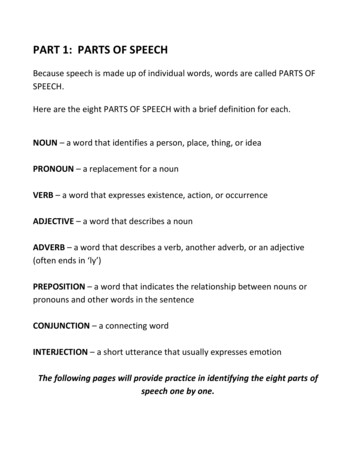

Transcription

This is “Your First Speech”, appendix 1 from the book Public Speaking: Practice and Ethics (index.html) (v. 1.0).This book is licensed under a Creative Commons by-nc-sa 3.0 ) license. See the license for more details, but that basically means you can share this book as long as youcredit the author (but see below), don't make money from it, and do make it available to everyone else under thesame terms.This content was accessible as of December 29, 2012, and it was downloaded then by Andy Schmitz(http://lardbucket.org) in an effort to preserve the availability of this book.Normally, the author and publisher would be credited here. However, the publisher has asked for the customaryCreative Commons attribution to the original publisher, authors, title, and book URI to be removed. Additionally,per the publisher's request, their name has been removed in some passages. More information is available on thisproject's attribution page utm source header).For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page(http://2012books.lardbucket.org/). You can browse or download additional books there.i

Chapter 19Your First SpeechLEARNING OBJECTIVES1. Understand the basic foundations of public speaking (speech purpose,topic selection, and audience analysis).2. Prepare a speech using appropriate research, solid organization, andsupporting evidence.3. Practice a speech using effective verbal and nonverbal deliverystrategies.4. Stand up and speak out! Thinkstock560

Chapter 19 Your First Speech19.1 The Public Speaking PyramidAncient Egyptians believed that the shape of a pyramid was very important andsacred because the triangular shape would help guide the deceased’s body towardthe stars into the afterlife. While this belief has long since disappeared, the idea of astructure guiding people in a specific direction toward greatness has remained.Figure 19.1 Public Speaking PyramidIn this brief appendix, we hope to start you on the path toward effective publicspeaking. To help us understand the basic process of public speaking, we havechosen to use a pyramid-based model of public speaking (). The rest of this chapteris going to briefly explain the basic public speaking process. We hope that thischapter will provide a simple overview of public speaking to help you develop yourfirst speech. Each of the concepts explored in this chapter is fully developedelsewhere in Stand Up, Speak Out, so don’t assume that this one chapter coverseverything you need to know.561

Chapter 19 Your First Speech19.2 Foundations of Public SpeakingEvery speech has to start somewhere, and one of the most common questions wehear from students in a public speaking course is, “Where do I start?” Well, yourpublic speaking teacher will definitely give you some specific guidelines for all thespeeches in your class, but all speeches start with the same basic foundation: speechpurpose, topic selection, and audience analysis.Speech PurposeThe very first question you’ll want to ask yourself is this: what is the basic purposeof the speech you’re about to give? As far back as the ancient Greeks, scholars ofpublic speaking have realized that there are three basic or general purposes peoplecan have for giving public speeches: to inform, to persuade, and to entertain.To InformThe first general purpose people can have for public speaking is to inform. When weuse the word “inform” in this context, we are specifically talking about giving otherpeople information that they do not currently possess. Maybe you’ve been asked totell the class about yourself or an important event in your life. For example, one ofour coauthors had a student who had been smuggled out of a totalitarian country asa small child with her family and fled to the United States, seeking asylum. Whenshe told the class about how this event changed her life, she wasn’t trying to makethe class do or believe anything, she was just informing the class about how thisevent changed her life.Another common type of informative speech is the “how-to” or demonstrationspeech. Maybe you’ll be asked to demonstrate something to the class. In this case,you’ll want to think about an interesting skill that you have that others don’tgenerally possess. Some demonstration speeches we’ve seen in the past haveincluded how to decorate a cake, how to swing a golf club, how to manipulate apuppet, and many other interesting and creative speeches.To PersuadeThe second general purpose that public speakers can have is to persuade. When youpersuade another person, you are attempting to get that person to change her orhis thought process or behavior. In the first case, you’re trying to get someone tochange her or his opinion or belief to what you, as the speaker, want that person tothink or believe after the speech. For example, maybe you belong to a specific562

Chapter 19 Your First Speechreligious group that doesn’t always get the greatest press. In your speech, you couldtry to tell your classmates where that negative press is coming from and all thegood that your religious sect does in the world. The goal of this speech isn’t toconvert people, it’s just to get people to think about your group in a more positivefashion or change their thought process.The second type of persuasive speech, the more common of the two, is to getsomeone to change her or his behavior. In this case, your goal at the end of thespeech is to see your audience members actually do something. When we want anaudience to do something at the end of the speech, we call this a “call to action”because we are actually asking our audience members to act on what we’ve saidduring the speech. For example, maybe you’re an advocate for open-source (or free)software packages. So you give a speech persuading your classmates to switch fromMicrosoft Office to OpenOffice (http://www.openoffice.org). In your speech, youcould show how the cost of Microsoft Office is constantly rising and that OpenOfficeoffers the exact same functionality for free. In this case, the goal of your speech isto have your classmates stop using Microsoft Office and start using OpenOffice—youwant them to act.To EntertainThe third general purpose people can have for public speaking is to entertain. Somespeeches are specifically designed to be more lighthearted and entertaining foraudience members. Quite often these speeches fall into the category of “afterdinner speeches,” or speeches that contain a serious message but are delivered in alively, amusing manner that will keep people alert after they’ve finished eating abig meal. For this reason, most speeches that fall into the “to entertain” categoryare either informative or persuasive, but we categorize them separately because ofreliance on humor. Effective speeches in this category are often seen as theintersection of public speaking and stand-up comedy. The speeches themselvesmust follow all the guidelines of effective public speaking, but the speeches must beable to captivate an audience through interesting and funny anecdotes and stories.Some common entertaining speech topics include everything from crazy e-mailspeople have written to trying to understand our funny family members.Not all entertaining speeches include large doses of humor. Some of the mostmemorable speakers in the professional speaking world fall into the entertainingcategory because of their amazing and heart-wrenching stories. The more seriousspeakers in this category are individuals who have experienced great loss orovercome enormous hurdles to succeed in life and who share their stories in acompelling style of speaking. Audience members find these speakers “entertaining”because the speakers’ stories captivate and inspire. In the professional world ofspeaking, the most commonly sought after form of speaker is the one who19.2 Foundations of Public Speaking563

Chapter 19 Your First Speechentertains an audience while having a serious message but delivering that messagein a humorous or entertaining manner.Topic SelectionOnce you have a general purpose for speaking (to inform, to persuade, or toentertain), you can start to develop the overarching topic for your speech. Clearly,some possible speech topics will not be appropriate for a given general purpose. Forexample, if you’ve been asked to give an informative speech, decrying the ills ofsocial policy in the United States would not be an appropriate topic because it’sinnately persuasive.In a public speaking class, your teacher will generally give you some parameters foryour speech. Some common parameters or constraints seen in public speakingclasses are general purpose and time limit. You may be asked to give a two- tothree-minute informative speech. In this case, you know that whatever you chooseto talk about should give your listeners information they do not already possess,but it also needs to be a topic that can be covered in just two to three minutes.While two to three minutes may seem like a long time to fill with information, thoseminutes will quickly disappear when you are in front of your audience. There aremany informative topics that would not be appropriate because you couldn’tpossibly cover them adequately in a short speech. For example, you couldn’t tell ushow to properly maintain a car engine in two to three minutes (even if you spokereally, really fast). You could, on the other hand, explain the purpose of acarburetor.In addition to thinking about the constraints of the speaking situation, you shouldalso make sure that your topic is appropriate—both for you as the speaker and foryour audience. One of the biggest mistakes novice public speakers make is pickingtheir favorite hobby as a speech topic. You may love your collection of beat-up golfballs scavenged from the nearby public golf course, but your audience is probablynot going to find your golf ball collection interesting. For this reason, whenselecting possible topics, we always recommend finding a topic that has crossoverappeal for both yourself and your audience. To do this, when you are considering agiven topic, think about who is in your audience and ask yourself if your audiencewould find this topic useful and interesting.Audience AnalysisTo find out whether an audience will find a speech useful and interesting, we gothrough a process called audience analysis. Just as the title implies, the goal of19.2 Foundations of Public Speaking564

Chapter 19 Your First Speechaudience analysis is to literally analyze who is in your audience. The following aresome common questions to ask yourself: Who are my audience members?What characteristics do my audience members have?What opinions and beliefs do they have?What do they already know?What would they be interested in knowing more about?What do they need?These are some basic questions to ask yourself. Let’s look at each of them quickly.Who Are My Audience Members?The first question asks you to think generally about the people who will be in youraudience. For example, are the people sitting in your audience forced to be there ordo they have a choice? Are the people in your audience there to specifically learnabout your topic, or could your topic be one of a few that are being spoken about onthat day?What Characteristics Do My Audience Members Have?The second question you want to ask yourself relates to the demographic makeup ofyour audience members. What is the general age of your audience? Do they possessany specific cultural attributes (e.g., ethnicity, race, or sexual orientation)? Is thegroup made up of older or younger people? Is the group made up of females, males,or a fairly equal balance of both? The basic goal of this question is to make sure thatwe are sensitive to all the different people within our audience. As ethical speakers,we want to make sure that we do not offend people by insensitive topic selection.For example, don’t assume that a group of college students are all politically liberal,that a group of women are all interested in cooking, or that a group of elderlypeople all have grandchildren. At the same time, don’t assume that all topic choiceswill be equally effective for all audiences.What Opinions and Beliefs Do They Have?In addition to knowing the basic makeup of your audience, you’ll also want to havea general idea of what opinions they hold and beliefs they have. While speakers areoften placed in the situation where their audience disagrees with the speaker’smessage, it is in your best interest to avoid this if possible. For example, if you’regoing to be speaking in front of a predominantly Jewish audience, speaking aboutthe virtues of family Christmas celebrations is not the best topic.19.2 Foundations of Public Speaking565

Chapter 19 Your First SpeechWhat Do They Already Know?The fourth question to ask yourself involves the current state of knowledge for youraudience members. A common mistake that even some professional speakers makeis to either underestimate or overestimate their audience’s knowledge. When weunderestimate an audience’s knowledge, we bore them by providing basicinformation that they already know. When we overestimate an audience’sknowledge, the audience members don’t know what we’re talking about becausethey don’t possess the fundamental information needed to understand theadvanced information.What Would They Be Interested in Knowing More About?As previously mentioned, speakers need to think about their audiences and whattheir audiences may find interesting. An easy way of determining this is to askpotential audience members, “Hey, what do you think about collecting golf balls?”If you receive blank stares and skeptical looks, then you’ll realize that this topicmay not be appropriate for your intended audience. If by chance people respond toyour question by asking you to tell them more about your golf ball collection, thenyou’ll know that your topic is potentially interesting for them.What Do They Need?The final question to ask yourself about your audience involves asking yourselfabout your audience’s needs. When you determine specific needs your audiencemay have, you conduct a needs assessment. A needs assessment helps you todetermine what information will benefit your audience in a real way. Maybe youraudience needs to hear an informative speech on effective e-mail writing in theworkplace, or they need to be persuaded to use hand sanitizing gel to prevent thespread of the flu virus during the winter. In both cases, you are seeing that there isa real need that your speech can help fill.19.2 Foundations of Public Speaking566

Chapter 19 Your First Speech19.3 Speech PreparationOnce you’ve finished putting in place the foundational building blocks of theeffective public speaking pyramid, it’s time to start building the second tier. Thesecond tier of the pyramid is focused on the part of the preparation of your speech.At this point, speakers really get to delve into the creation of the speech itself. Thislevel of the pyramid contains three major building blocks: research, organization,and support.ResearchIf you want to give a successful and effective speech,you’re going to need to research your topic. Even if youare considered an expert on the topic, you’re going toneed do some research to organize your thoughts forthe speech. Research is the process of investigating arange of sources to determine relevant facts, theories,examples, quotations, and arguments. The goal ofresearch is to help you, as the speaker, to become veryfamiliar with a specific topic area. ThinkstockWe recommend that you start your research by conducting a general review of yourtopic. You may find an article in a popular-press magazine like Vogue, SportsIllustrated, Ebony, or The Advocate. You could also consult newspapers or newswebsites for information. The goal at this step is to find general information thatcan help point you in the right direction. When we read a range of general sources,we’ll start to see names of commonly cited people across articles. Often, the peoplewho are cited across a range of articles are the “thought leaders” on a specific topic,or the people who are advocating and advancing how people think about a topic.Once you’ve identified who these thought leaders are, we can start searching forwhat they’ve written and said directly. At this level, we’re going from looking atsources that provide a general overview to sources that are more specific andspecialized. You’ll often find that these sources are academic journals and books.One of the biggest mistakes novice public speakers can make, though, is to spend somuch time reading and finding sources that they don’t spend enough time on thenext stage of speech preparation. We recommend that you set a time limit for howlong you will spend researching so that you can be sure to leave enough time to567

Chapter 19 Your First Speechfinish preparing your speech. You can have the greatest research on earth, but ifyou don’t organize it well, that research won’t result in a successful speech.OrganizationThe next step in speech preparation is determining the basic structure of yourspeech. Effective speeches all contain a basic structure: introduction, body, andconclusion.IntroductionThe introduction is where you set up the main idea of your speech and get youraudience members interested. An effective introduction section of a speech shouldfirst capture your audience’s attention. The attention getter might be an interestingquotation from one of your sources or a story that leads into the topic of yourspeech. The goal is to pique your audience’s interest and make them anticipatehearing what else you have to say.In addition to capturing your audience’s attention, the introduction should alsocontain the basic idea or thesis of your speech. If this component is missing, youraudience is likely to become confused, and chances are that some of them will “tuneout” and stop paying attention. The clearer and more direct you can be with thestatement of your thesis, the easier it will be for your audience members tounderstand your speech.BodyThe bulk of your speech occurs in what we call “the body” of the speech. The bodyof the speech is generally segmented into a series of main points that a speakerwants to make. For a speech that is less than ten minutes long, we generallyrecommend no more than two or three main points. We recommend this becausewhen a speaker only has two or three main points, the likelihood that an audiencemember will recall those points at the conclusion of the speech increases. If you arelike most people, you have sat through speeches in which the speaker rambled onwithout having any clear organization. When speakers lack clear organization withtwo or three main points, the audience gets lost just trying to figure out what thespeaker is talking about in the first place.To help you think about your body section of your speech, ask yourself thisquestion, “If I could only say three sentences, what would those sentences be?”When you are able to clearly determine what the three most important sentencesare, you’ve figured out what the three main points of your speech should also be.19.3 Speech Preparation568

Chapter 19 Your First SpeechOnce you have your two or three main topic areas, you then need to spend timedeveloping those areas into segments that work individually but are even moremeaningful when combined together. The result will form the body of your speech.ConclusionAfter you’ve finished talking about the two or three main points in your speech, it’stime to conclude the speech. At the beginning of the speech’s conclusion, youshould start by clearly restating the basic idea of your speech (thesis). We restatethe thesis at this point to put everything back into perspective and show how thethree main points were used to help us understand the original thesis.For persuasive speeches, we also use the conclusion of the speech to make a directcall for people change their thought processes or behaviors (call to action). We savethis until the very end to make sure the audience knows exactly what we, thespeaker, want them to do now that we’re concluding the speech.For informative speeches, you may want to refer back to the device you used to gainyour audience’s attention at the beginning of the speech. When we conclude backwhere we started, we show the audience how everything is connected within ourspeech.Now that we’ve walked through the basic organization of a speech, here’s a simpleway to outline the speech:1. Introduction1. Attention getter2. Thesis statement2. Body of speech1. Main point 12. Main point 23. Main point 33. Conclusion1. Restate thesis statement2. Conclusionary device 1. Call to action 2. Refer back to attention getter19.3 Speech Preparation569

Chapter 19 Your First SpeechSupportYou may think that once you’ve developed your basic outline of the speech, thehard part is over, but you’re not done yet. An outline of your speech is like the steelframe of a building under construction. If the frame isn’t structurally sound, thebuilding will collapse, but no one really wants to live in an open steel structure. Forthis reason, once you’ve finished creating the basic structure of your speech, it’stime to start putting the rest of the speech together, or build walls, floors, andceilings to create a completed building.For each of the two or three main points you’ve picked in your speech, you need tonow determine how you are going to elaborate on those areas and make them fullyunderstandable. To help us make completed main points, we rely on a range ofsupporting materials that we discovered during the research phase. Supportingmaterials help us define, describe, explain, and illustrate the main points weselected when deciding on the speech’s organization. For example, often there arenew terms that need to be defined in order for the audience to understand the bulkof our speech. You could use one of the sources you found during the research stageto define the term in question. Maybe another source will then help to illustratethat concept. In essence, at this level we’re using the research to support thedifferent sections of our speech and make them more understandable for ouraudiences.Every main point that you have in your speech should have support. Forinformative speeches, you need to provide expert testimony for why something istrue or false. For example, if you’re giving a speech on harmfulness of volcanic gas,you need to have evidence from noted researchers explaining how volcanic gas isharmful. For persuasive speeches, the quality of our support becomes even moreimportant as we try to create arguments for why audience members should changetheir thought processes or behaviors. At this level, we use our supporting materialsas evidence in favor of the arguments we are making. If you’re giving a speech onwhy people should chew gum after meals, you need to have expert testimony (fromdentists or the American Dental Association) explaining the benefits of chewinggum. In persuasive speeches, the quality of your sources becomes very important.Clearly the American Dental Association is more respected than Joe Bob who livesdown the street from me. When people listen to evidence presented during aspeech, Joe Bob won’t be very persuasive, but the American Dental Association willlend more credibility to your argument.19.3 Speech Preparation570

Chapter 19 Your First Speech19.4 Speech PracticeOnce you’ve finished creating the physical structure ofthe speech, including all the sources you will use tosupport your main points, it’s time to work ondelivering your speech. The old maxim that “practicemakes perfect” is as valid as ever in this case. We arenot downplaying the importance of speech preparationat all. However, you could have the best speech outlinein the world with the most amazing support, but if yourdelivery is bad, all your hard work will be lost on youraudience members. In this section, we’re going tobriefly talk about the two fundamental aspects relatedto practicing your speech: verbal and nonverbaldelivery. ThinkstockVerbal DeliveryVerbal delivery is the way we actually deliver the words within the speech. Youmay, or may not, have noticed that up to this point in this chapter we have not usedthe phrases “writing your speech” or “speech writing.” One of the biggest mistakesnew public speakers make is writing out their entire speech and then trying to readthe speech back to an audience. You may wonder to yourself, “Well, doesn’t thepresident of the United States read his speeches?” And you’re right; the presidentgenerally does read his speeches. But he also had years of speaking experienceunder his belt before he learned to use a TelePrompTer.While reading a speech can be appropriate in some circumstances, in publicspeaking courses, the goal is usually to engage in what is called extemporaneousspeaking. Extemporaneous speaking involves speaking in a natural, conversationaltone and relying on notes rather than a prepared script. People who need to readspeeches typically do so for one of two reasons: (1) the content of their speech is sospecific and filled with technical terminology that misspeaking could causeproblems, or (2) the slightest misspoken word could be held against the speakerpolitically or legally. Most of us will not be in either one of those two speakingcontexts, so having the stuffiness and formalness of a written speech isn’t necessaryand can actually be detrimental.So how does one develop an extemporaneous speaking style? Practice! You’vealready created your outline, now you have to become comfortable speaking from aset of notes. If you put too much information on your notes, you’ll spend more time571

Chapter 19 Your First Speechreading your notes and less time connecting with your audience. Notes should helpyou remember specific quotations, sources, and details, but they shouldn’t containthe entire manuscript of your speech. Learning how to work with your notes andphrase your speech in a comfortable manner takes practice. It’s important to realizethat practice does not consist of running through your speech silently in your mind.Instead, you need to stand up and rehearse delivering your speech out loud. To getused to speaking in front of people and to get constructive feedback, and werecommend that you ask a few friends to serve as your practice audience.Nonverbal DeliveryIn addition to thinking about how we are going to deliver the content of the speech,we also need to think about how we’re going to nonverbally deliver our speech.While there are many aspects of nonverbal delivery we could discuss here, we’regoing to focus on only three of them: eye contact, gestures, and movement.Eye ContactOne of the most important nonverbal behaviors we can exhibit while speaking inpublic is gaining and maintaining eye contact. When we look at audience membersdirectly, it helps them to focus their attention and listen more intently to what youare saying. On the flip side, when a speaker fails to look at audience members, it’seasy for the audience to become distracted and stop listening. When practicing yourspeech, think about the moments in the speech when it will be most comfortable foryou to look at people in your audience. If you have a long quotation, you’ll probablyneed to read that quotation. However, when you then explain how that quotationrelates to your speech, that’s a great point to look up from your notes and looksomeone straight in the eye and talk to them directly. When you’re engaging in eyecontact, just tell yourself that you’re talking to that person specifically.GesturesA second major area of nonverbal communication for new public speakers involvesgesturing. Gesturing is the physical manipulation of arms and hands to addemphasis to a speech. Gestures should be meaningful while speaking. You want toavoid being at either of the extremes: too much or too little. If you gesture toomuch, you may look like you’re flailing your arms around for no purpose, which canbecome very distracting for an audience. At the same time, if you don’t gesture atall, you’ll look stiff and disengaged. One of our friends once watched a professor(who was obviously used to speaking from behind a lectern) give a short speechwhile standing on a stage nervously gripping the hems of his suit coat with bothhands. Knowing how to use your hands effectively will enhance your delivery andincrease the impact of your message.19.4 Speech Practice572

Chapter 19 Your First SpeechIf you’re a new speaker, we cannot recommend highly enough the necessity ofseeing how you look while practicing your speech, either by videotaping yourself orby practicing in front of a full-length mirror. People are often apprehensive aboutwatching video tapes of themselves speaking, but the best way to really see how youlook while speaking is—well, literally to see how you look while speaking. Think ofit this way: If you have a distracting mannerism that you weren’t conscious of,wouldn’t you rather become aware of it before your speech so that you can practicemaking an effort to change that behavior?MovementThe last major aspect of nonverbal communication we want to discuss here relatesto how we move while speaking. As with gesturing, new speakers tend to go to oneof two extremes while speaking: no movement or too much movement. On the oneend of the spectrum, you have speakers who stand perfectly still and do not move atall. These speakers may also find comfort standing behind a lectern, which limitstheir ability to move in a comfortable manner. At the other end of the spectrum arespeakers who never stop moving. Some even start to pace back and forth whilespeaking. One of our coauthors had a student who walked in a circle around thelectern while speaking, making the audience sligh

Figure 19.1 Public Speaking Pyramid. In this brief appendix, we hope to start you on the path toward effective public speaking. To help us understand the basic process of public speaking, we have chosen to use a pyramid-based model of public speaking (). The rest of this chapter is going to briefly ex