Transcription

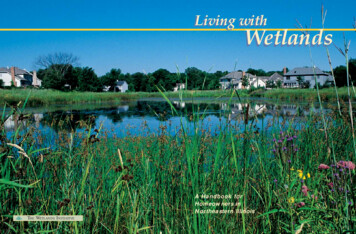

Living withwithLivingWetlandsA Handbook forHomeowners inNortheastern IllinoisThe Wetlands Initiative

1Living with WetlandsDear Homeowner:When you chose to live near a wetland, you included one of nature’smost unique creations in your backyard. You have a front row seat towatch these amazing ecosystems at work—purifying water, holdingfloodwaters, providing homes to all kinds of wildlife. The value and enjoyment of your home are enhanced when a wetland is nearby.This handbook is intended to help you understand the wetland inyour backyard so you can enjoy it more. Also, with understanding, wehope, will come an increased willingness to be a responsible steward of thisnatural area.A handbook for homeowners in Northeastern IllinoisWHAT’S INSIDE:Wetlands and youpage 2Defining a wetlandpage 4Great EgretSincerely,Albert E. PyottPresident, The Wetlands InitiativeGrass PinkTaking a closer lookpage 6Protecting wetlandspage 10Frog & DuckweedProduced byThe Wetlands InitiativeIn partnership withU.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Chicago Field OfficeU.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Chicago Districtwith funding from the Grand Victoria Foundationand Chicago WildernessRed-winged BlackbirdBeing a good neighborEggs & Nest of Red-winged BlackbirdManaging your wetlandText by Laura UrbanBook Design & Illustrations by Nancy WilliamsonTechnical AdviserWilliam J. Mitsch, Ph.D., The Ohio State Universitypage 12MuskratFinding help 1998 The Wetlands InitiativeÊPrinted on recycled paper with soy-based inkLesser Yellowlegspage 20page 16

32Wetlands andand youyouWetlandsWetlands are valuable to you and yourcommunity because they:Improve water quality.Wetlands can absorb and filter outpollutants and sediments in the water.Store floodwaters.Tall Meadow Rue &Baltimore CheckerspotWetlands are a sponge, slowing downthe force of flood and storm waters asthey travel downstream.Offer habitat for wildlife.Duck PotatoNew England Asterfor industry and medicine. Wetlandsare one of the most productive ecosystems on earth because they producemore living things per acre than otherecosystems.Provide valuable open space.Homeowners enjoy the scenic vistasand the increased privacy that comefrom living near wild areas. Propertyvalues usually are enhanced whenhomes are properly built near healthywetlands.Many migratory birds and otherwildlife found in Illinois depend onwetlands for survival.Create recreationalopportunities.Support biodiversity.Fishing, birdwatching, and hiking arejust a few of the activities people enjoyin wetland areas.The wide variety of living thingsmakes the health of our planet andour own lives possible by ensuringour food supply, regulating the atmosphere, and providing raw materialsSneeze WeedGreen HeronSwamp MilkweedCommon BurreedGreat EgretFor nearly 200 years these values were unappreciatedacross the country. The nation’s rich “swamp lands” wereviewed only as areas waiting for “improvement.” The city ofChicago was even built atop drained and filled wetlands! Mostnaturally-occurring wetlands in Illinois have been drained,filled, channelized (or otherwise converted) to farms, homes,and businesses. Today less than 10% of the wetlands present inIllinois in the early 1800s remain.The functional values of our remaining wetlands can bediminished when the ecosystem becomes unbalanced by toomuch sediment or pollution, or if the areas immediatelyadjacent to wetlands are not maintained with native plantspecies. Healthy wetlands need neighbors who are goodstewards and managers of these ecosystems.Sawtooth SunflowerFemale Red-winged Blackbird

45Defining aa wetlandwetlandDefiningAt its simplest definition, a wetland is an area between deep water and dry land. It may holdstanding water year-round or for only a few weeks in the rainy season; but regardless of howlong it is wet, to be called a wetland, it must be an area where the soil was formed by and plantshave adapted to water.Don’t be surprised if you don’t always recognize a wetland. Identifying some wetlands takesspecialized training in soil science, botany, and hydrology. Wetland delineation is the processecologists use to identify wetlands and determine their boundaries. While you may not be a wetland scientist, you can learn to recognize the common wetland types in northeastern Illinois.Skunk CabbageTypes of wetlands in IllinoisBlueFlag IrisForested wetland—Many of these wetlands are next to a river, where their waterlevel fluctuates with the river level. Otherforested wetlands are in poorly drained uplandareas. Both types typically only have standing water during partof the growing season. Silver or red maple, green and black ash,willow or alder trees abound in these wetlands. Forested wetlands provide habitat for wood ducks, woodpeckers, salamanders, and wildflowers such as jack-in-the-pulpit.Marsh—Marshes account for about 90 percent ofthe total wetlands in northeastern Illinois. Shallow ordeep marshes (with water depth of only a few inchesto a few feet) have year-round standing water androoted plants that emerge above water, called emergents, such as bulrush, cordgrass and cattails. Muskratsand frogs, as well as mallards, teal, and other birds—including many state threatened or endangered species—nest, breed, and feed here.Wetland mitigation projectsA wetland mitigation project is an area where scientists and engineers have createdor restored wetlands to lessen the impact of deliberate wetland loss elsewhere. Theseprojects often—though not always—are on land that historically had been a wetlandbefore the land had been drained for farming or other development.These projects have been mandated by Section 404 of the federal Clean WaterAct (see Protecting wetlands, page 10). This law requires that if a developer or anindividual is permitted to adversely impact a wetland, then they must mitigate orcompensate for that impact. For example,if a developer fills one acre of wetland forhis or her project, he or she typically willbe required to restore, enhance or createone or more acres of wetlands elsewhere—either on or off the property. This is anexpensive undertaking, costing developers 40,000 to 100,000 per acre in construction and planting costs, not including thecost of the land itself. Therefore, it is inthe best interest of all those involved to domitigation correctly.If the wetland near your home is partof a mitigation project, the U.S. ArmyCorps of Engineers will have required thatthe developer maintain and monitor thewetland for the first five years after construction. Ask your homebuilder whatregulations apply to your wetland or callthe Corps (see Finding help, page 20).Grass-of-ParnassusDetention basin or wetland?MarshMarigoldWet meadow —Wet meadows have saturated soil and little standing water. Sedgemeadows have saturated soil that supportssedges—a plant that is most recognizable in earlyspring by its lumpy tufts of grass-like shoots. Wet prairies are wetmeadows which are dominated by grasses and wildflowers. Wetmeadows are home to a variety of wildlife species, includingvoles, short-eared owls, sandhill cranes, and marsh hawks.Bog and fen—Bogs are known for theirwaterlogged peat and dense coverings ofsphagnum mosses which grow in a bog’sacidic environment. A fen develops in an alkaline area, where groundwater flows through calcium- or magnesium-rich glacial deposits and seeps out to the surface. Manyrare and interesting plants are found only in bogs or fens.A detention pond is a manmade basin designed to holdwater that used to be absorbed into the soil, but now runs offimpervious areas (e.g., your home, driveway, roads, andmowed lawns). Rainwater and snow melt accumulates in thebasin and then is slowly released to a nearby creek orstream. These basins may be surrounded by concrete andmowed grass, rather than by native vegetation. In the 1980s,some of these basins were considered wetlands by theCorps, and, therefore, were regulated by the Corps. Morerecent detention ponds usually are not regulated by theCorps. If you're in doubt about whether the detention basinin your area is regulated as a wetland, ask the Corps.In this sample wetlandmitigation site plan, openwater and emergent marshareas (bottom center) wereenlarged and enhanced tocompensate for the loss ofwetlands in another area.

76Taking a closer lookYou’ll enjoy your neighboring wetlandmore if you understand its complexity andbeauty. Start by going on a nature walk andobserving it closely. Look for the following:WaterWood DuckDuckweedWhere does the water in your wetlandcome from? Does it flow out of the wetland? Where does it go? How does thewater level vary with the season andthe year?Look for the sources of waterto your wetland and where thewater exits. If there are culverts or outlet pipes, makesure they aren’t blocked withsediment or debris. Notice howthe water level will fluctuate with theseasons and the rainfall. This is natural—infact, beneficial—because the fluctuationregenerates vegetation, recycles nutrients,and reduces algae growth.If you live in an area where homeshave been flooded, try to determine why.The numberson a county soilmap indicatedifferent soiltypes, includinghydric soils. Ingeneral, hydricsoils have watertables that arecloser to thesurface thanother soils.Blue-green algaeWhat's thatgreen stuff?Don't confuse algae withthe tiny, floating plant familycalled duckweed—lesser duckweed and its cousin, watermeal. The round or ovalleaves of these plants are lessthan one-quarter inch longand can be mistaken for algalblooms. Filamentous algae willappear as greenish, stringyslime. Duckweed is an important food for waterfowl.DuckweedPond with algae matsWater from a healthy wetland canappear various colors, depending on theweather and the biological activity in thewater. Water will often appear to be stainedbrown like tea, although when scooped upin a glass, the water will look clear. Thebrown hue is perfectly natural and comesfrom tannic acids that are released asorganic matter (e.g., leaves, stems, andorganisms) decomposes in the wetland.Water that appears a muddy, chocolatebrown, however, is not natural. This coloris caused by too much silt and sedimentwashing into the wetland. Muddy-waterwetlands can’t support a complete foodweb because plants and small organismswill become smothered under accumulatedsediment, and sight-feeding fish will starvein the murky water.In early summer, the water may appeargreen—it may even look as if its beenstreaked with radiator coolant. This iscaused by growth of planktonic algae,Are culverts clogged? Has stormwaterrunoff increased as roads, parking lots, andother impervious areas have expandedaround the wetland?Every wetland is part of a largerwatershed, the land area that water flowsacross or under on its way to the lowestpoint, that is, a stream, river, lake, or wetland. By knowing where your wetland issituated in the watershed, you’ll betterunderstand how you and your neighborsaffect water quality and flooding downstream. Take a look around your neighborhood to determine where the rain goeswhen it falls. If it drains into a storm sewer,see if you can find where it re-emerges.(Your county stormwater managementcommission or department of environmentwill be able to help you with this.) Doeswater from your wetland eventually flow toa river or a lake?If your wetland has standing water,notice its quality. What color is the water?Is the water turbid or dirty? How muchalgae is present?Closeup of algaesmall organisms suspended in open water.In mid- and late-summer, the water mayappear black. This occurs when the waterlevel is low and the algae and plant production is highest, thus, there is very little oxygen in the water.If you see algae, try to assess howmuch is present. Some algae growth is anatural phenomenon and essential to building the food web. Too much algae willcause other aquatic plant life to suffocate,leaving only the mosquitoes to flourish.Think of algae as a warning flag: If thewater surface of a wetland is covered withit, the natural balance of nutrients in thewater has been upset, most likely due toexcess fertilizer washing into the wetland.Septic field leachate, stormwater runoff andanimal excrement also can increase nutrients in a wetland (see Being a good neighbor,pages 12-13).Why is my backyard(or basement) wet?While some residents who live near wetlandsmay believe that wetlands cause flooding, the opposite is actually true. Wetlands act as a sponge,absorbing rainwater and runoff. The soil can actuallyhold water, preventing it from racing downstream.Wetlands, however, form at low points in thelandscape and water will collect there. Wetlandsalso may indicate that the water table, the level ofwater in the ground, is close to the surface. Thus, ifpeople build basements, backyards, or roads in awetland or below the water table of a wetland,flooding will occur.Before you buy or remodel a home, you canlearn about the topography, soils, wetlands,and the water table on the property by askingyour local Natural Resources ConservationService office or county Soil and WaterConservation District (see Finding help, page20) for a Soil Survey Report of your area.

89VegetationHow many different types of plants do yousee in the wetland and surrounding area? Arethere a few species that cover the whole area?How do the plants change as you get fartheraway or closer to the water?To a society accustomed to manicuredlawns and tidy rows of flowers, wetland vegetation can look unkempt and weedy. Unlike shortturf grasses that we plant for lawns, however,wetland plants are perfectly suited for their environment. The tall grasses, reeds, and rushes havedeep, strong roots that hold the soil and absorbnutrients out of the wetland. Their bushy topsare homes to many species of birdsand insects who are vital to the1ecosystem’s food web, including the damselfliesand dragonflies who eat mosquitoes.Look for different vegetation communities,groups of plants that grow together due to similar soil and water conditions. Buy or borrow aguidebook specific for wetland plants and learnto identify what you see. Attend nature walkssponsored by forest preserve districts, naturecenters, park districts, or conservation groups.SoilHow does the soil change color and textureas you get closer to the water level? Does thissoil look different than the soil in your yard?Soil in wetlands, called hydric soil, is shapedby the presence of water during the growing season. The soil generally has a deep, dark surfacelayer followed by a grayer subsoil layer that mayhave reddish splotches. Rich organic areas willhave deposits of peat or muck—black, highlydecomposed plants. For further informationabout soil around your home, contact your Soiland Water Conservation District office (seeFinding Help, page 20).in local wetlands, including the yellow-headedblackbird, pied-billed grebe, great egret, andblack-crowned night heron.Various water and soil conditions in and around awetland affect what species live and grow there. Thisillustration is roughly arranged from plants thatfavor drier conditions (starting left) to plants thatneed standing water (right). See if you can find these speciesaround your wetland. 1. Big Bluestem 2. Yellow Coneflower3. Blue Vervain 4. Prairie Dock 5. Spotted Joe Pye Weed6. Switch Grass 7. Monarch Butterfly 8. Wild Bergamot9. Common Sneeze Weed 10. Nannyberry Bush 11. Red OsierDogwood 12. Common Boneset 13. Sawtooth Sunflower14. Green Darner Dragonfly 15. Bristly Sedge 16. BroadleafArrowhead (Duck Potato) 17. Blue Flag Iris 18a. Common WaterPlantain (with bloom) 18b. Common Water Plantain 19. SoraRail 20. River Bulrush 21. Sweet Flag 22. White Water Lily23. Cattail 24. Water Boatman 25. Leopard Frog 26. WoodDuck 27. Soft-Stem Bulrush 28. Water Smartweed29. Common Burreed 30. Peachleaf WillowWildlifeWhat animals do you see, particularly inearly morning or early evening? Do you seetracks, droppings, nests, or holes? How manydifferent types of bird songs or frog calls canyou hear? Can you find small animals such asfrogs, butterflies, dragonflies, or salamanders?Wetlands are home to many diverse species,from large to small, from airborne to aquatic.Observing wildlife in its own habitat can be oneof the most enjoyable aspects of living near awetland. Attend a birdwatching group’s localwalk to learn the names and sounds of commonbirds. Several rare and unusual birds are 191718b2429

1011Protecting wetlandsFor more than a century, we havedrained, filled, dredged, dammed, andaltered our nation’s wetlands with theencouragement and support of the federalgovernment. In the past 25 years, however,we have begun to recognize that these landsare invaluable resources to landowners, thecommunity, and the entire nation. Todaywetlands are protected by legislation, ordinances, easements, and deed restrictions.Federal LawThe Blandings turtle,once common innortheastern Illinois,has been eliminatedthroughout much of itsrange by habitat loss.Section 404 of the Clean Water Actrequires that anyone obtain a permit beforeplacing dredged or fill material in anywaters of the United States. Most wetlandsare considered waters of the United States;stormwater detention basins typically arenot, and, therefore, may not be regulatedby the Corps.Activities such as filling, grading,mechanized land clearing, excavating, orinstalling rock riprap or seawalls all are regulated by the Corps. Individuals mustapply for a permit from theCorps before doing theseactivities. Copies of the permitapplication must be forwardedto the Illinois Department ofNatural Resources and the Illinois EPA,and should be sent to the U.S. Fish andWildlife Service (see Finding help, page 20).The law also requires that developersor individuals avoid or minimize theimpacts to wetlands when building homesor businesses. If they can’t avoid impactingthe wetland areas on their property, theCorps may allow them to mitigate for thedamage to wetlands by restoring previouslyconverted wetlands, enhancing degradedwetlands, or creating new wetlands. This iscalled wetland mitigation.Ask your homebuilder if the wetlandsin your area were subject to mitigation orpreservation action by the Corps. If so, thedeveloper or the homeowners’ associationmay still be obligated to manage or maintain the wetland. Check your homeowner’sassociation agreement, covenant or easement documents. Call the RegulatoryBranch of the Corps if you have questions(see Finding help, page 20).State LawThere are no state laws specifically regulating wetlands; however, if constructionprojects occur in wetlands in a floodplainor in areas adjacent to a public water body(e.g., the Chain O’Lakes or the Fox River),they will be regulated. Small wetlands inresidential areas are not regulated by thestate. Contact the Illinois Department ofNatural Resources, Office of WaterResources, for further information (seeFinding help, page 20).Local/County OrdinancesSome municipalities or county governments have their own ordinances restrictingwhat activities are allowed in and around awetland. In 1988 the Northeastern IllinoisPlanning Commission developed a modelwetland protection ordinance which somelocal officials have adopted. Check withyour municipal or county zoning officeabout what restrictions, permits, or bufferzones apply in your area.Conservation EasementsSome wetlands may be protected by aconservation easement. This is an agreement between the landowner and a thirdparty (such as a homeowners’ association,park district, forest preserve district, or conservation organization) granting certainrights concerning the use of a piece ofproperty without transferring ownership ofthat land. The developer may have createdthe easement at the time of development torestrict how the property is used.If your property is adjacent to a wetland in a newer subdivision, 30 to 50 feetor more of your lot may be under a conservation easement. If so, you are not allowedto build fences, swing sets, or sheds on thatportion of your lot. Planting trees, mowing, dumping, or fertilizing also may bebanned. The easement may require that abuffer of native vegetation be maintainedaround the wetland.Ask your homeowners’ association,builder, or local conservation organizationif the wetlands near your home areprotected—or could be protected—by aconservation easement. If your land isalready under an easement, make sure youunderstand how the easement restricts youractivity. (See Finding help, page 21, fornon-profit organizations that can help youwith establishing conservation easements.)Deed RestrictionsA deed restriction is similar to a conservation easement in that it restricts whatactivities the landowner can do on his orher land or the land owned by the homeowner’s association. A clause in the property deed places restrictions on the use ofthat land.In the past decade, the U.S. ArmyCorps of Engineers has required deedrestrictions on homes that border a wetlandproject permitted by its office. Morerecently, deed restrictions are placed on“out lots” or common areas that includethe wetland. These areas are then held bythe homeowners’ association.Deed restrictions also can be mandatedby city or county governments. Check yourproperty title or ask your homebuilderwhat restrictions are on your property.Conservation easementsand deed restrictions aredesigned to give a wetland the natural vegetated zone that it needsto stay healthy. The 2550 feet around yourwetland may be undersuch a restriction. Checkwith your developer orread your property deed.

1213Being a good neighborThe common yellowthroat is an abundantwetland warbler easilyrecognized by hisblack “mask” and“witchitywitchity”song.When you live near a wetland, youlive near an important natural resource.You have the opportunity—indeed, theresponsibility—to be a steward of thatresource. Start by being a good neighborto the wetland. Practice the following environmentally-sensitive activities to decreasethe amount of nutrients, pollutants, andsediment that enter the wetland.Establish adjacent stripsof native vegetation.One of the most important ways youcan care for a wetland is to give it space. Awetland that is crowded by pavement,mowed grass, or adjacent development maybecome overloaded with nutrients (e.g.,phosphorus, nitrogen) from fertilizer andwith sediment carried by storm runoff. Awetland without native vegetation aroundit also will lose much of its habitat valueto wildlife.Feeding your lawn or your wetland?Many homeowners fertilize their lawn several times a seasonwith “combination” fertilizers (containing nitrogen, phosphorus andpotassium) whether the soil is hungry or not. Your soil may not needall three nutrients, and, by dumping the product on your lawn, it willwash into the wetland, feeding only the algae.If your lawn or garden beds look unhealthy, start with otherremedies before you fertilize. First, aerate your soil with arototiller or a shovel so that roots can penetrate into the compacted clay. Then, conduct a soil test using a kit ( 15- 20)available at your local nursery to measure the nutrients andpH level. Apply fertilizer based on what your soil reallyneeds. When you are finally ready to fertilize, listen to theweather report first. Avoid applying fertilizer before a heavyrain, which will wash the nutrients away before they areabsorbed by the soil.To protect a wetland from adjacent humanactivity, a vegetative strip of native plants—not mowed grass—should be maintainedaround the wetland. This strip is simply anupland area that is maintained with nativevegetation. A conservation easement ordeed restriction may be in effect on yourlot to provide for this strip. If not, you asthe landowner adjacent to the wetland maychoose to voluntarily leave this area innative plantings.The primary benefit that a vegetativestrip provides is its ability to filter outnutrients and pollutants before they reachthe wetland. The deep, dense roots ofnative plants take up nutrients deposited inthe soil from local runoff. Native uplandvegetation slows the speed of the surfacewater reaching the wetland, thus, reducingerosion. The tall grasses of these areas alsoprovide habitat and links to other habitatsin the area (either other wetlands or nearbyupland areas).For a list of recommended species toplant in these areas, request a free copy ofShoreline Buffer Strips from the Northeastern Illinois Planning Commission (seeFinding Help, p. 23). Once vegetative stripsare established (within 1–3 years), theyrequire little maintenance. Occasionalmowing or burning may be necessary tocontrol weeds and maintain native plantdiversity. Only mow after midsummer, soas not to disrupt any wildlife nests.Fertilizers should not be used in these areas.Use chemicals sparingly.Whatever chemicals you use in youryard can wash into a wetland, eitherdirectly or via a nearby storm sewer. Becareful how and when you use lawn fertilizer, pesticides, car cleansers, road salt,and motor oil.Without a vegetativestrip of native plants,road and yard chemicalsmay wash directly intoan adjacent wetland.Filter strips trap chemicalsand slow stormwaterthat rushes off asaturated lawn.

1415Don’t dump on(or in) your wetland.A wetland is not a compost pilefor your grass clippings, a depository for manure or pet droppings,or a convenient place to leave junk,debris, or unused chemicals.Treat your wetland as youwould your own garden and don’tsuffocate it with a pile of grassclippings. Heaps of grass clippings in your wetland will forman oxygen-starved mass thatwill not decay, but will cause afoul smell and will upset thebalance within the wetland ecosystem. Contact yourcounty’s University of IllinoisCooperative Extension Service forinformation on how to properlycompost your yard waste (seeFinding help, page 20).Animal waste in or near a wetland will reduce its water quality, aswill unused chemicals. If you havematerials that you think might behazardous or toxic to plants orwildlife, contact the Illinois EPA oryour municipality and ask about ahousehold hazardous waste collection day in your area.Keep pets outof wild areas.Your lovable and tame house cat canbecome an effective predator when left to runloose around a wetland. Cats can catch mice,voles, and nesting or feeding birds. Dogs alsocan wreak havoc for small animals and nestingbirds. Leash your dog or provide a fenced areafor him or her so he or she cannot harass thevery wildlife you are trying to protect.Maintain yourseptic system.Bull FrogIf your home has a septic system, you maybe tempted to assume all is working well unlessyou see (or smell) otherwise. But if you waituntil there’s an obvious problem, your systemmay contaminate your well water and yournearby wetland in the meantime. Incompletelytreated septic system waste may be slowly send-Slider TurtlesYellow-headed BlackbirdScreech OwlSharing your land with wildlifeYou can do more than protect the wildlife that shares your land; you can conserveand improve its habitat. The Illinois Department of Natural Resources has biologistsand literature available, through the “Acres for Wildlife” landowner assistance program, to help you. IDNR staff can suggest helpful plantings or how to construct artificial nest structures and brush piles for animals to use. Staff also may be available foran educational program to your homeowner’s group (see Finding help, page 20).Mayfly on LadyslipperA septic field that is placed too close toa wetland or is improperly maintainedmay damage the water quality of anearby wetland.ing phosphorus-rich effluent to your wetland,adding to the algae and cattail build-up.Start by inspecting your tank every year todetermine the sludge level. Hire a contractor topump the tank when the sludge exceeds onethird of the tank volume (to leave room in thetank for solids to settle out before the sewageliquid enters the soil absorption field).Check to see that your system has sufficiently dry soil in the absorption field. Fieldsthat are too near the water table or are inpoorly-drained soils will cause untreated wastewater to flow to the surface or seep to thegroundwater and into your wetland.Even a properly designed, constructed, andmaintained system only lasts about 20 years(depending on the usage). After that time, thecapacity of the soil to renovate the wastewateris reduced. Older systems may need upgradingor replacement. For further information, contact your county health department. (For available video, see Finding help, page 23.)

1617Managing youryour wetlandwetlandManagingToday ecologists know that just as gardens need tending, urban natural areas suchas wetlands, prairies, and forests also needspecialized care or management. Althoughwetlands functioned successfully for centurieswithout human help, they also existed without human disturbance. In urbanized area,today’s wetlands are no longer connected toprairies where animal migrations, freely flowing water, and periodic wildfires once sustained and naturally “managed” these ecosystems. Therefore, if these remaining wetlandsare going to be—or become—ecologicallyhealthy, they need human help.That help includes planting native plants(or sowing seeds), removing unwanted invasive plants, performing prescribed burning,and monitoring the plants and animals toassess their ecological health. These tasks areusually done by professional ecologists. Somework, however, could be done by trained volunteers (see Finding help, pages 21-22 fornon-profit organizations that offer training).Because of the largescale of managementPurple beauty or menace?work, most activitiesare initiated and paidfor by a homeowners’Purple loosestrife (Lythrum saligroup, not an individcaria) is a pretty, spiky flower thatblooms from early July to earlyual landowner.September. Its role in a wetland,however, is far from delightful.Because each plant produces over100,000 to 1 million seeds eachyear, it grows rapidly, uncheckedby disease or insects, and chokesout native plants. This

wetlands for survival. Support biodiversity. The wide variety of living things makes the health of our planet and our own lives possible by ensuring our food supply, regulating the atmos-phere, and providing raw materials for industry and medicine. Wetlands are one of the