Transcription

AustraliaCorporate Responsibility —A Guide for Australian Directors

“Corporations are not responsible for all the world’sproblems, nor do they have the resources to solvethem all. Each company can identify the particular setof societal problems that it is best equipped to helpresolve and from which it can gain the greatestcompetitive benefit. Addressing social issues bycreating shared value will lead to self-sustainingsolutions that do not depend on private or governmentsubsidies. When a well-run business applies its vastresources, expertise, and management talent toproblems that it understands and in which it has astake, it can have a greater impact on social good thanany other institution or philanthropic organisation.”Porter, M.E. and Kramer, M.R. “Strategy and Society: the link between competitiveadvantage and corporate social responsibility,”

Corporate Responsibility: A Guide for Australian DirectorsForewordThe purpose of this Guide is to explore the idea of corporate social responsibilityor, as it is now increasingly referred to, corporate responsibility (CR). Althoughwritten with company directors in mind it may also be helpful to senior managerswho are responsible for implementing Board decisions.Andrew Beatty is a coordinator ofBaker & McKenzie’s globalcorporate responsibility practice.Baker & McKenzie’s corporateresponsibility team advises clientsaround the world on current andemerging legal and policy trends.Andrew BeattyPartnerTel: 61 2 8922 5632andrew.beatty@bakernet.comA great deal has already been written about CR and the flow of opinion andinformation is still growing. In part, this is a motivation for the preparation ofthe Guide. As directors are already confronted by so much information on somany seemingly vital business topics, extreme or simplistic views can sometimesappear most compelling to the time poor.The other motivation for writing this Guide is an unashamedly subjective one.The authors feel that CR, at least as we define it, is not only now a permanentfeature of the corporate landscape, it has the potential to be a valuable competitivetool when properly used.A glossary of terms and acronyms begins the Guide.AcknowledgementsLed by Andrew Beatty, this Guide has been prepared by members of the Environmentand Environmental Markets team in Sydney, and, in particular, Evan Williams,Paul Curnow, Louisa Fitz-Gerald, Eric Knight, Karen Gould and Samantha Brand.The law is stated to be correct as at March 2007.Baker & McKenzieSydneyAustralia

DisclaimerBaker & McKenzie International is a Swiss Verein with member law firms around the world. In accordance with the common terminology used inprofessional service organisations, reference to a “partner” means a person who is a partner, or equivalent, insuch a law firm. Similarly, referenceto an “office” means an office of any such law firm.The information contained in this guide should not be relied on as legal or investment advice and should not be regarded as a substitute for detailed advicein individual cases. No responsibility for any loss occasioned to any person by acting or refraining from action as a result of material in this guide is acceptedby Baker & McKenzie.The law is stated as at March 2007, unless otherwise indicated. 2007 Baker & McKenzieAll rights reserved.

Corporate Responsibility: A Guide for Australian DirectorsContentsGlossary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .11.2.3.4.5.6.Introduction – CR What does it mean? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .51.1CSR or CR . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 51.2Our definition of CR in this Guide . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 51.3Approaches to CR. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 51.4The “business” approach . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6CR: Some Statistics . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .82.1Global Context . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 82.2Australian Context . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 92.3Socially Responsible Investment (SRI) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10Voluntary CR Initiatives . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .123.1Voluntary Reporting . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 123.2Voluntary Compliance . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 143.3Market and Industry Based Initiatives . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16CR: Legal Obligations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .214.1Traditional obligations of a CR nature . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 214.2Corporate Governance . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21CR: Key Issues . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .265.1Social . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 265.2Labour. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 305.3Environment . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 325.4Transparency . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 36CR: Is it for you? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .396.1The bottom line . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 396.2Risk management . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 406.3Employee recruitment and retention . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 406.4Beyond compliance . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 416.5Brand image and reputation. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 427.Conclusions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .438.Bibliography . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .449.Websites . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .47i

Corporate Responsibility: A Guide for Australian DirectorsGlossaryACCOUNTABILITY 1000AA1000. International standard for independently verifying the social and ethical accounting,auditing and reporting of companies developed by the UK-based Institute for Social and EthicalAccountability (ISEA).AS 8003-2003Australian Standard on “Corporate governance - Corporate social responsibility.ASX COUNCILRECOMMENDATIONSPrinciples and Recommendations issued by the ASX Corporate Governance Council outlining aframework for good corporate governance which applies to listed companies and trusts. Theyare not mandatory requirements to which companies must adhere but, under the ASX ListingRules, listed entities must report against the Recommendations annually under an “if not, whynot” reporting requirement.CAERCentre for Australian Ethical Research.CAMACCorporations and Markets Advisory Committee. This committee established under Part 9 of theAustralian Securities and Investment Commission Act 1989, advises the Australian Governmenton the operation and reform of corporations legislation, the efficiency of financial markets andthe regulation of companies generally.CARBON NEUTRALPhrase used to describe an activity that produces no net Greenhouse Gas emissions. Prominentcompanies including IAG, HSBC and BSkyB have adopted the goal of attaining carbon neutralstatus. A company can achieve carbon neutral status by reducing their overall emissions andpurchasing carbon offsets (e.g. carbon credits) or investing directly in activities that reduce theamount of CO2e in the atmosphere.CDP4The Carbon Disclosure Project is a program where institutional investors collectively sign a singleglobal request for disclosure of information on greenhouse gas emissions and climate change riskby the largest companies in the world. The first request was sent in 2002, resulting in thepublication of the CDP1 report in 2003. The CDP4 report was released 2006. The request forinformation to be compiled into CDP5 was sent to companies in February 2007.CLOSED LOOPSystem in which all wastes are recycled or re-used so that no new materials are needed toprovide a new generation of products.CO2eCarbon dioxide equivalent. There are a range of Greenhouse Gases that contribute to thegreenhouse effect and climate change. However, each contributes to different degrees (i.e. theyhave a different Global Warming Potential). For example one molecule of methane has the sameeffect as 21 molecules of carbon dioxide. For ease of calculation emissions of GHGs other thanCO2 are described in terms of the equivalent number of molecules of CO2 that they represent.CRCorporate Responsibility. Also sometimes referred to as Business Responsibility. See CSR andTBL.CRIAustralian Corporate Responsibility Index. Reporting initiative overseen by the St James EthicsCentre which allows companies to voluntarily assess their CR performance. The CRI is based ona program developed by the UK organisation “Business in the Community.”CSRCorporate Social Responsibility. In this Guide the term corporate responsibility (CR) has beenused to refer issues traditionally understood to be covered by the term corporate socialresponsibility. Typically CSR covers a range of corporate activities which extend beyondtraditional legal compliance requirements in the areas of social and labour policy,environmental protection, corporate governance and the like.DOW JONESSUSTAINABILITYINDEX (DJSI)Index designed to measure the corporate sustainability of companies. The leading 10% ofcompanies in terms of sustainability out of the biggest 2,500 companies on the Dow JonesGlobal Index, and the top 20% of the Dow Jones STOXX 600 are rated. I nvestment managers in14 countries hold licences to use the DJSI to assess and manage financial products.1

Baker & McKenzieECOLOGICALFOOTPRINTA measure of a individual or organisation’s impact on the environment, an ecological footprint is arepresentation of the total quantity of resources that are used directly and indirectly as a resultof the organisation’s activities. The original means of representing an ecological footprint wasby quantifying the area of land required to support resource use.EIAEthical Investment Association Australasia.EQUATOR PRINCIPLESA framework for banks to manage the environmental and social issues of projects for which theyare giving project financing. Signatories to the Principles agree not to loan money to a projectwith a total capital cost of US 10 million unless the sponsors of the project comply withrequirements to undertake environmental and social assessments and, in some cases, todevelop management plans for the environmental and social impacts of the project.ESD1.the precautionary principle – if there are threats of serious or irreversible environmentaldamage, lack of full scientific certainty should not be used as a reason for postponingmeasures to prevent environmental degradation;2.inter-generational equity – the present generation should ensure that the health, diversityand productivity of the environment are maintained or enhanced for the benefit of futuregenerations;3.conservation of biological diversity and ecological integrity;4.improved valuation, pricing and incentive mechanisms – environmental factors should beincluded in the valuation of assets and services.ESGEnvironmental, Social and Governance factors. Phrase used alternatively with CR in somearenas.FOREIGN CORRUPTPRACTICES ACTUS law that outlaws the bribery of foreign public officials by US citizens or corporations. TheForeign Corrupt Practices Act was the first law of its kind, preceding the OECD Anti-BriberyConvention by 20 years. In 1998 the Act was amended to conform with the Anti-BriberyConvention.FTSE4GOODIndex developed by FTSE Group to measure the performance of companies that meet globallyrecognised corporate responsibility standards: used to guide Socially Responsible Investment.G250Global Fortune Top 250 companies. Classification used in the KPMG International Survey ofCorporate Responsibility Reporting to mean the top 250 companies on the Fortune Global 500list. The Global 500 list is compiled by ranking corporations according to reported revenues.GREENHOUSE GAS orGHGGHG. Gas that contributes to the Greenhouse Effect by preventing the escape of radiant heatfrom the Earth’s atmosphere. Greenhouse Gases include carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4),nitrous oxide (NO3), ozone, water vapour and chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs).GREENHOUSECHALLENGE PLUSAustralian Government Initiative aimed at promoting industry-government partnerships. GreenhouseChallenge Plus combines the Greenhouse Challenge (which was established in 1995), GreenhouseFriendly and Generator Efficiency Standards. Companies that sign up enter into a contract with theGovernment outlining each parties’ obligations. The scheme is designed to encourage companies toreport and reduce their greenhouse gas emissions.GRIGlobal Reporting Initiative. Organisation that produces non-financial reporting guidelines forcompanies.IFCInternational Finance Corporation. The private sector arm of the World Bank which aims topromote sustainable private sector investment in developing countries.2

Corporate Responsibility: A Guide for Australian DirectorsIGOInter-Governmental Organisation (or multilateral agencies). Any body that is structured aroundcooperation or negotiation between national governments. Examples are the UN, the World Bankand the OECD.ILOInternational Labor Organisation.ISEAInstitute for Social and Ethical Accountability.ISO 26000Guideline on Social Responsibility being developed by the International Standards Organisation,which is expected to be released in 2008.JANTZI SOCIAL INDEXSocially screened, market capitalisation-weighted share index consisting of 60 Canadiancompanies that pass a set of broadly based environmental, social, and governance ratingcriteria. The aim of the index is to provide a benchmark against which investment managers cancompare the performance of their SRI funds. The Index was established in partnership with theDJSI.JSE SRI INDEXJohannesburg Securities Exchange Sustainable Responsible Investment Index. An indexdesigned to measure and identify the level of compliance by companies with therecommendations in the King Report.KING REPORTThe King Committee on Corporate Governance (South Africa) produced a report in 1994 whichwas updated and re-released in 2002. The 2002 report is considered by many to set thebenchmark for best practice in corporate governance and has been used as a model for CRlegislation in other jurisdictions.KYOTO PROTOCOLAn international agreement that requires developed countries to reduce their GHG emissions byan average of 5.2% below 1990 levels by 2008-2012. It was adopted by all Parties to theUNFCCC in Kyoto, Japan, in December 1997. Despite the US and Australia not yet ratifying thetreaty, it entered into force in February 2005.MNEMultinational Enterprise. A corporation that has production facilities in, or that delivers servicesin, at least two countries.MULTILATERALAGENCIESSee IGO.NATIONAL PACKAGINGCOVENANT or NPCA voluntary agreement between all levels of government in Australia and companies ororganisations that sign it aimed at increasing the proportion of packaging that is recycled andreducing the volume of packaging waste ending up in landfill. Brand owners that elect not tosign the NPC may be subject to state legislation which implements the National EnvironmentProtection Measure on Used Packaging Materials (NEPM).NGONon-Governmental Organisation, e.g. Greenpeace.OECD GUIDELINESFOR MNESVoluntary, non-binding guidelines released by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation andDevelopment for MNEs.PJCParliamentary Joint Committee on Corporations and Financial Services.REPUTEX SRISRI Index that ranks a selected companies from the S&P/ASX 300 Index.SAMSustainability Asset Management Australia.SMESmall to Medium Sized Enterprises.SRISocially Responsible Investment (also known as Sustainable Responsible Investment).SUSTAINABILITYThe ability to meet the needs of the present generation without compromising the ability offuture generations to meet their own needs.TBLTriple Bottom Line. Concept of reporting, decision-making or risk assessment taking into accountsocial, economic and environmental impacts rather than just the traditional economic bottomline.3

Baker & McKenzieTRANSPARENCYINTERNATIONALInternational NGO that works to eliminate corporate corruption.UN UNIVERSALDECLARATION ONHUMAN RIGHTSStatement of human rights recognised by General Assembly of the United Nations in1948. Rights recognised in the Declaration include the right of equal treatment ofhuman beings, the right to a fair trial, the right of freedom of expression and the rightsto freedom from slavery and torture.UNEPUnited Nations Environment Programme. Arm of the United Nations responsible for theUN-administered environmental initiatives.UNFCCCUnited Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change.UN GLOBAL COMPACTInitiative of the United Nations that facilitates a network of UN agencies, governments,business, labour, and non-government organisations to encourage companies to adopta set of principles of corporate citizenship.UN PRIUnited Nations Principles for Responsible Investment. Voluntary, aspirational principlesto guide large institutional investors (in particular pension and superannuation funds)and asset managers towards corporate social and environmental responsibility.Established by UN Global Compact and the United Nations Environment ProgrammeFinance Initiative.WORLD BANKSAFEGUARDSEnvironmental and social safeguard policies designed to prevent and mitigate undueharm to people and their environment during the development process. The policiesare used as a guide by World Bank staff in the identification, preparation, andimplementation of programs and projects.4

Corporate Responsibility: A Guide for Australian DirectorsSummary There is a continuing debateover both the definition of, andthe terminology that should beused to describe, corporateresponsibility. We set out our definition ofcorporate responsibility for thepurposes of this Guide. The Australian Corporationsand Markets AdvisoryCommittee (CAMAC) hasidentified five approachesto corporate responsibility: 1.Introduction – CR What doesit mean?1.1 CSR or CRPractitioners of, and commentators on, CSR tend nowadays to talk of “corporateresponsibility” (or ”business responsibility”) rather than corporate social responsibility.We have adopted this shorter phrase in the knowledge that it too may soon becomeunfashionable, much like the phrase Triple Bottom Line.1.2 Our definition of CR in this GuideFor the purposes of this Guide, we define CR as:a voluntary and public act by a company intended to address the economic, socialand/or environmental impacts of its current or likely future business activities forthe benefit of its shareholders and those affected by its business operations.-business-compliance-philanthropicOur definition necessarily excludes:-social primacy-social obligation mere compliance with applicable laws and in particular laws regulating safety,health, environment, labour standards or corrupt practices;Australian regulators currentlyendorse the business approachto corporate responsibilitywhich involves little, if any,government intervention orany mandatory requirementsfor stand alone CR activity orreporting. actions taken solely for the benefit of persons unaffected by a company’s currentor likely future business operations; and corporate philanthropy or charitable giving.Whilst it is argued that charitable donations (or sponsorships of sporting or culturalevents) are ultimately undertaken for the benefit of shareholders (by reason ofimproving the donor’s image and therefore attractiveness to investors or others),our view is that these types of activities tend to equate more easily with marketing.Our preferred definition (which is a relatively narrow one) is focused on thoseactivities most likely to be accepted as part of corporate conduct which remainslargely unregulated1 and therefore still productive of competitive differentiation.Although our definition excludes some activities which others label as “CR,” thisGuide is intended to survey the field, and so does consider activities which wewould not include in our definition.1.3 Approaches to CRThere are a great many definitions of CR, some contradictory to others. A usefulsummary of the competing definitions of CR is provided in the report of theCorporations and Markets Advisory Committee (CAMAC), The Social Responsibilityof Corporations, released on 12 December 20062. As part of a comprehensivesurvey of the current issues surrounding CR around the world, and in Australia,the Committee identified five approaches to CR: The “business” approach: it is in the direct interests of companies to engagein CR practices, because it will assist in managing risk (both financial and nonfinancial) and create a suite of benefits for the company.1We recognise that there are an increasing number of legal or semi-legal requirements on certaintypes of companies to report on CR activities – e.g., listing requirements, accounting policies andsome corporations laws. The regulation of CR is examined in Chapter 4.2Available at /PDFFinal Reports 2006/ file/CSR Report.pdf. For a summary and analysis of the CAMAC report with respect to CR seeBeatty, A. and Williams, E., “CSR and corporate governance: the reviews continue,” Keeping goodcompanies 59(2) (March 2007), 74-79.5

Baker & McKenzie The “compliance” approach: legal compliance, which may be simply meetinga company’s obligations as strictly interpreted, or going further and attemptingto comply with the “spirit” of the law as well. The “philanthropic” approach: companies make financial and non-financial donationsto the community in ways beyond their core business activities, because suchgiving will provide some benefit to the company (such as improved staff morale,recruitment advantages, improved reputation in the marketplace and so on) andto the communities in which they may operate (or hope to operate) or otherwiseaffect. Such philanthropy may include, for example, charitable donations, corporatesponsorship of the arts, donations to benevolent foundations, staff volunteeringtime to participate in community projects or workplace giving programs. The “social primacy” approach: corporate decision-making should incorporateethical standards that go beyond both the letter and the spirit of the law, evenwhere this does not result in any particular corporate benefit. For example,a company may choose not to do business with a company that has breachedhuman rights standards abroad, even where this would mean foregoing asignificant business opportunity. The “social obligation” approach: corporations have a responsibility to act forthe benefit of the community because they have access to significant and valuableresources that, on one hand, have the potential to make a significant contributionto public welfare and, on the other, if not used wisely may deprive others ofaccess to these resources where they may have some legal or moral claim orentitlement to them.1.4 The “business” approachIn its 2006 report, CAMAC concluded: The interests of shareholders should not be subordinated to other “stakeholders”but, “awareness of relevant environmental and social considerations is part of anystrategy to promote the continuing well-being of the company and to maximiseshareholder value over the longer term.”3 In short, CAMAC endorsed the“business” approach as the model of CR that should guide corporations andregulators in Australia. The relevance of particular social and environmental matters will vary, dependingon the nature of a company’s business.4 While directors may choose to do more to address certain social or environmentalissues they see as relevant to their business, companies do not “bear some formof obligation to tackle wider problems facing society, regardless of the relevanceof those problems to their own business.” The “philanthropic” approach to CR – where companies pursue CR and sustainabilityissues above and beyond their primary business activity – has no real place inCR practices when it is used to justify an unhealthy level of discretion affordedto directors in spending shareholders’ funds. CR is not an add-on: it is a central concern to how a company runs its affairs.However this does not mean that companies should disregard business objectivesin pursuit of solutions to environmental and social problems.3CAMAC, The Social Responsibility of Corporations (December 2006), at 78.4Ibid.6

Corporate Responsibility: A Guide for Australian DirectorsThe Parliamentary Joint Committee (PJC) on Corporations and Financial Services5and the ASX Corporate Governance Council6 also endorse the “business” approachto CR and recognise the need for corporate regulation to provide flexibility tobusinesses so as not to stifle business activity. In Australia, therefore, CR is understoodby regulators to be something that should be accommodated within business goalsand that it should not undermine the rights of shareholders or the importance ofshareholder interests in corporate decision making.5Parliamentary Joint Committee on Corporations and Financial Services, Corporate SocialResponsibility: Managing risk and creating value (June 2006).Available at s ctte/corporate responsibility/report/6ASX Corporate Governance Council, Review of the Principles of Good Corporate Governance and BestPractice Recommendations: Explanatory Paper and Consultation Paper (November 2006). Available athttp://www.asx.com.au/supervision/pdf/asxgc explanatory paper consultation paper 021106.pdf7

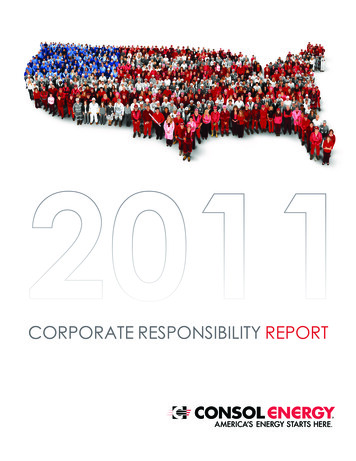

Baker & McKenzie2.CR: Some Statistics2.1 Global ContextMost CR activities tend to be conducted or at least subsequently reported on in public.CR (or non-financial) reporting is the clearest sign of CR. CR reporting is becomingincreasingly common among the world’s largest companies and, increasingly, amongstpublic sector businesses7. Statistics on the extent of reporting amongst the world’slargest companies have been compiled by a number of organisations and internationalmanagement firms.The KPMG International Survey of Corporate Social Responsibility Reporting 2005(KPMG Survey8) made the following findings: 52% of the Global Fortune Top 250 companies (G250) issued stand-aloneCR publications in 2005. This was up from 45% of companies in 2002. 64% of the G250 provided sustainability reporting either in stand-aloneCR publications or within their annual financial reports in 2005. In 2005 almost 70% of the G250 reports covered social, environmental andeconomic criteria compared with 2002 where the content mainly coveredenvironmental, health and safety criteria.The KPMG Survey also identified the participation in CR reporting from theG250 according to industry sectors.The strongest participants were: Chemicals and Synthetics: 100% Electronics and computers: 91% Utilities: 92% Oil & gas: 80% Automotive: 85%In contrast, the weakest participants included: Trade and retail: 31% Communication: 47%The strongest growth in reporting performance between 2003 and 2005 was in thefinance, securities and insurance sectors where reporting increased 138% to 57% ofcompanies providing stand-alone reports in 2005.7In addition, many Governments (including the Australian Commonwealth, State and Territorygovernments) produce State of the Environment (SoE) reports as part of a UNEP program forglobal environmental assessment.These reports assess a range of environmental indicators andare compiled at global, regional, national and sub-national levels. For more information see:http://www.grida.no/soe/8The report was produced in conjunction with the University of Amsterdam. It is available athttp://www.kpmg.nl/Docs/Corporate Site/Publicaties/International Survey Corporate Responsibility 2005.pdf8Summary CR reporting activity is on therise globally and in Australia. There is some variation in theuptake of CR reporting acrossdifferent industries in Australia. The rise in Socially (or Sustainable)Responsible Investment (SRI) isevidence of a desire amongstinvestors for companies toconsider CR issues. Many shareholders are nownot just interested in makingmoney but want to know howthat money is made.

Corporate Responsibility: A Guide for Australian DirectorsCorporate responsibility (CR) reporting by sector, Global 250 (2002, e 200573%2002Oil & gas 200580%58%2002Trade & retail 200531%26%200292%Utilities 200558%2002100%Pharmaceuticals 200596%200247%Communication & media 2005200220027024%2002Electronics & computers 2005Chemicals & synthetics 20056057%Finance, securities & insurance 200541%100%100%Number and percentage of companies withCR reports (separate and published as partof annual reports)Total number of companies in the sec

recognised corporate responsibility standards: used to guide Socially Responsible Investment. G250 Global Fortune Top 250 companies. Classification used in the KPMG International Survey of