Transcription

Literature Circle Guide:The Cayby Susan Van ZileSCHOLASTICPROFESSIONALBOOKSNew York Toronto London Auckland Sydney Mexico City New Delhi Hong Kong Buenos AiresLiterature Circle Guide: The Cay Scholastic Teaching Resources

Scholastic Inc. grants teachers permission to photocopy the reproducibles from this book for classroom use. Noother part of this publication may be reproduced in whole or in part, or stored in a retrieval system, or transmittedin any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without permissionof the publisher. For information regarding permission, write to Scholastic Professional Books, 557 Broadway,New York, NY 10012-3999.Guide written by Susan Van ZileEdited by Sarah GlasscockCover design by Niloufar SafaviehInterior design by Grafica, Inc.Interior illustrations by Mona MarkCredits: Cover: Jacket cover for THE CAY by Theodore Taylor. Used by permission of HarperCollins Publishers.Copyright 2002 by Scholastic Inc. All rights reserved.ISBN 0-439-35535-4Printed in the U.S.A.1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 104008 07 06 05 04 03 02Literature Circle Guide: The Cay Scholastic Teaching Resources

ContentsTo the Teacher. 4Using the Literature Circle Guides in Your Classroom . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5Setting Up Literature Response Journals . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7The Good Discussion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8About The Cay . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9About the Author: Theodore Taylor . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9Enrichment Readings: World War II, Coral Reefs, Curaçao . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .10Literature Response Journal Reproducible: Before Reading the Book . . . . . . . . . . . .13Group Discussion Reproducible: Before Reading the Book . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .14Literature Response Journal Reproducible: Chapters 1-2 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .15Group Discussion Reproducible: Chapters 1-2 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .16Literature Response Journal Reproducible: Chapters 3-4 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .17Group Discussion Reproducible: Chapters 3-4 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .18Literature Response Journal Reproducible: Chapters 5-7 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .19Group Discussion Reproducible: Chapters 5-7 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .20Literature Response Journal Reproducible: Chapters 8-9 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .21Group Discussion Reproducible: Chapters 8-9 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .22Literature Response Journal Reproducible: Chapters 10-11 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .23Group Discussion Reproducible: Chapters 10-11 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .24Literature Response Journal Reproducible: Chapters 12-14 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .25Group Discussion Reproducible: Chapters 12-14 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .26Literature Response Journal Reproducible: Chapters 15-16 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .27Group Discussion Reproducible: Chapters 15-16 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .28Literature Response Journal Reproducible: Chapters 17-19 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .29Group Discussion Reproducible: Chapters 17-19 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .30Reproducible: After Reading . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .31Reproducible: Individual Projects . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .32Reproducible: Group Projects . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .32Literature Discussion Evaluation Sheet . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .333Literature Circle Guide: The Cay Scholastic Teaching Resources

To the TeacherAs a teacher, you naturally want to instill in yourstudents the habits of confident, critical, independent, and lifelong readers. You hope that evenwhen students are not in school they will seek outbooks on their own, think about and questionwhat they are reading, and share those ideas withfriends. An excellent way to further this goal is byusing literature circles in your classroom.A Allow three or four weeks for students to readeach book. Each of Scholastic’s LiteratureCircle Guides has the same number of sectionsas well as enrichment activities and projects.Even if students are reading different books inthe Literature Circle Guide series, they can bescheduled to finish at the same time.A Create a daily routine so students can focusIn a literature circle, students select a book toread as a group. They think and write about it ontheir own in a literature response journal and thendiscuss it together. Both journals and discussionsenable students to respond to a book and developtheir insights into it. They also learn to identifythemes and issues, analyze vocabulary, recognizewriting techniques, and share ideas with eachother—all of which are necessary to meet stateand national standards.on journal writing and discussions.A Decide whether students will be reading booksin class or for homework. If students do alltheir reading for homework, then allot classtime for sharing journals and discussions. Youcan also alternate silent reading and writingdays in the classroom with discussion groups.This guide provides the support materials forusing literature circles with The Cay by TheodoreTaylor. The reading strategies, discussionquestions, projects, and enrichment readings willalso support a whole class reading of this text orcan be given to enhance the experience of anindividual student reading the book as part of areading workshop.Read More AboutLiterature CirclesGetting the Most from Literature Groupsby Penny Strube (Scholastic ProfessionalBooks, 1996)Literature Circles by Harvey Daniels(Stenhouse Publishers, 1994)Literature CirclesA literature circle consists of several students(usually three to five) who agree to read a booktogether and share their observations, questions,and interpretations. Groups may be organizedby reading level or choice of book. Often thesegroups read more than one book together since,as students become more comfortable talkingwith one another, their observations andinsights deepen.When planning to use literature circles in yourclassroom, it can be helpful to do the following:A Recommend four or five books from whichstudents can choose. These books might begrouped by theme, genre, or author.4Literature Circle Guide: The Cay Scholastic Teaching Resources

Using the Literature CircleGuides in Your ClassroomIf everyone in class is reading the same book,you may present the reading strategy as a minilesson to the entire class. For literature circles,however, the group of students can read over anddiscuss the strategy together at the start of classand then experiment with the strategy as theyread silently for the rest of the period. You maywant to allow time at the end of class so thegroup can talk about what they noticed as theyread. As an alternative, the literature circle canreview the reading strategy for the next sectionafter they have completed their discussion. Thatnight, students can try out the reading strategyas they read on their own so they will be readyfor the next day’s literature circle discussion.Each guide contains the following sections:A background information about the authorand bookA enrichment readings relevant to the bookA Literature Response Journal reproduciblesA Group Discussion reproduciblesA Individual and group projectsA Literature Discussion Evaluation SheetBackground Information andEnrichment Readings Literature Response Journal TopicsA literature response journal allows a reader to“converse” with a book. Students write questions,point out things they notice about the story, recallpersonal experiences, and make connections toother texts in their journals. In other words, theyare using writing to explore what they think aboutthe book. See page 7 for tips on how to helpstudents set up their literature response journals.The background information about the author andthe book and the enrichment readings are designedto offer information that will enhance students’understanding of the book. You may choose toassign and discuss these sections before, during,or after the reading of the book. Because eachenrichment concludes with questions that invitestudents to connect it to the book, you can use thissection to inspire them to think and record theirthoughts in the literature response journal.1. The questions for the literature responsejournals have no right or wrong answers butare designed to help students look beneath thesurface of the plot and develop a richerconnection to the story and its characters.Literature Response JournalReproducibles2. Students can write in their literature responsejournals as soon as they have finished a readingassignment. Again, you may choose to havestudents do this for homework or make timeduring class.Although these reproducibles are designed forindividual students, they should also be used tostimulate and support discussions in literaturecircles. Each page begins with a readingstrategy and follows with several journal topics.At the bottom of the page, students select atype of response (prediction, question,observation, or connection) for free-choicewriting in their response journals.3. The literature response journals are an excellenttool for students to use in their literature circles.They can highlight ideas and thoughts in theirjournals that they want to share with the group.4. When you evaluate students’ journals,consider whether they have completed all theassignments and have responded in depth andthoughtfully. You may want to check each dayto make sure students are keeping up with theassignments. You can read and respond to thejournals at a halfway point (after five entries)and again at the end. Some teachers suggestthat students pick out their five best entriesfor a grade. Reading StrategiesSince the goal of the literature circle is to empowerlifelong readers, a different reading strategy isintroduced in each section. Not only does thereading strategy allow students to understand thisparticular book better, it also instills a habit ofmind that will continue to be useful when theyread other books. A question from the LiteratureResponse Journal and the Group Discussion pagesis always tied to the reading strategy.5Literature Circle Guide: The Cay Scholastic Teaching Resources

4. It can be helpful to have a facilitator for eachdiscussion. The facilitator can keep students frominterrupting each other, help the conversation getback on track when it digresses, and encourageshyer members to contribute. At the end of eachdiscussion, the facilitator can summarize everyone’scontributions and suggest areas for improvement.Group Discussion ReproduciblesThese reproducibles are designed for use inliterature circles. Each page begins with a seriesof discussion questions for the group toconsider. A mini-lesson on an aspect of thewriter’s craft follows the discussion questions.See page 8 for tips on how to model gooddiscussions for students.5. Designate other roles for group members. Forinstance, a recorder can take notes and/or listquestions for further discussion. A summarizercan open each literature circle meeting bysummarizing the chapter(s) the group has justread. Encourage students to rotate these roles, aswell as that of the facilitator. Literature Discussion Questions: In aliterature discussion, students experience a bookfrom different points of view. Each reader bringsher or his own unique observations, questions,and associations to the text. When studentsshare their different reading experiences, theyoften come to a wider and deeper understandingthan they would have reached on their own. The Writer’s Craft: This section encouragesstudents to look at the writer’s most importanttool—words. It points out new vocabulary,writing techniques, and uses of language. One ortwo questions invite students to think moredeeply about the book and writing in general.These questions can either become part of theliterature circle discussion or be written about instudents’ journals.The discussion is not an exercise in finding theright answers nor is it a debate. Its goal is toexplore the many possible meanings of a book.Be sure to allow enough time for theseconversations to move beyond easy answers—try to schedule 25–35 minutes for each one. Inaddition, there are important guidelines toensure that everyone’s voice is heard.Literature DiscussionEvaluation Sheet1. Let students know that participation in theliterature discussion is an important part of theirgrade. You may choose to watch one discussionand grade it. (You can use the LiteratureDiscussion Evaluation Sheet on page 33.)Both you and your students will benefit fromcompleting these evaluation sheets. You can usethem to assess students’ performance, and asmentioned earlier, students can evaluate their ownindividual performances, as well as their group’sperformance. The Literature Discussion EvaluationSheet appears on page 33.2. Encourage students to evaluate their ownperformance in discussions using the LiteratureDiscussion Evaluation Sheet. They can assessnot only their own level of involvement but alsohow the group itself has functioned.3. Help students learn how to talk to oneanother effectively. After a discussion, help themprocess what worked and what didn’t. Videotapediscussions if possible, and then evaluate themtogether. Let one literature circle watch anotherand provide feedback to it.6Literature Circle Guide: The Cay Scholastic Teaching Resources

Setting Up LiteratureResponse Journalscertain words, phrases, or passages in a book.Others note the style of an author’s writing orthe voice in which the story is told. A studentjust starting to read The Cay might writethe following:Although some students may already keepliterature response journals, others may notknow how to begin. To discourage students frommerely writing elaborate plot summaries and toencourage them to use their journals in ameaningful way, help them focus their responsesaround the following elements: predictions,observations, questions, and connections. Havestudents take time after each assigned section tothink about and record their responses in theirjournals. Sample responses appear below.I notice Phillip feels “excited” about thewar, “not frightened.” I wonder if that’swhy he disobeys his mother and goes toFort Amsterdam with Henrik van Boven.But, after the army officer tells Phillip hecould be killed by a torpedo, Phillip isfrightened. Then he seems to view the waras real, not as an adventure. Questions: Point out that good readers don’t Predictions: Before students read the book,necessarily understand everything they read. Toclarify their uncertainty, they ask questions.Encourage students to identify passages thatconfuse or trouble them, and emphasize thatthey shouldn’t take anything for granted. Sharethe following student example:have them study the cover and the jacket copy.Ask if anyone has read any other books byTheodore Taylor. To begin their literatureresponse journals, tell students to jot down theirimpressions about the book. As they read,students will continue to make predictions aboutwhat a character might do or how the plot mightturn. After finishing the book, students can reassess their initial predictions. Good readersunderstand that they must constantly activateprior knowledge before, during, and after theyread. They adjust their expectations andpredictions: a story that is completely predictableis not likely to capture anyone’s interest. Astudent about to read The Cay might predictthe following:What will happen to Phillip? Why does hismother want to take him back to Virginia?Doesn’t she realize their ship could beblown up? If she wants to protect Phillip,why won’t she fly to Virginia? Will Curaçaobe bombed? Connections: Remind students that onestory often leads to another. When one friendtells a story, the other friend is often inspired totell one, too. The same thing happens whensomeone reads a book. A character reminds thereader of a relative, or a situation is similar tosomething that happened to him or her.Sometimes a book makes a reader recall otherbooks or movies. These connections can behelpful in revealing some of the deeper meaningsor patterns of a book. The following is anexample of a student connection:Looking at the book jacket makes mewonder how the blind white boy Phillip willget along with the old black man. I thinkthe two will have problems because I seethe words black vs. white. It will take a lotof courage and determination to survive onthe island. Observations: This activity takes placeI keep thinking about Phillip’s sadness as heleaves Curaçao. I felt the same way whenmy family moved. His reaction makes methink things will get worse for him beforethey get better. That’s what happened to me.immediately after reading begins. In a literatureresponse journal, the reader recalls freshimpressions about the characters, setting, andevents. Most readers mention details that standout for them even if they’re not sure what theirimportance is. For example, a reader might listphrases that describe how a character looks orthe feeling a setting evokes. Many readers note7Literature Circle Guide: The Cay Scholastic Teaching Resources

The Good Discussionwith a discussion so students can try out whatthey learned from the first one.In a good literature discussion, students arealways learning from one another. They listen toone another and respond to what their peershave to say. They share their ideas, questions,and observations. Everyone feels comfortableabout talking, and no one interrupts or putsdown what anyone else says. Students leave agood literature discussion with a newunderstanding of the book—and sometimes withnew questions about it. They almost always feelmore engaged by what they have read. Assessing Discussions: The following tips Modeling a Good Discussion: In this era of3. The group should look at the LiteratureDiscussion Evaluation Sheet and assess theirperformance as a whole. Were most of thebehaviors helpful? Were any behaviorsunhelpful? How could the group improve?will help students monitor how well their groupis functioning:1. One person should keep track of all behaviorsby each group member, both helpful andunhelpful, during the discussion.2. At the end of the discussion, each individualshould think about how he or she did. Howmany helpful and unhelpful checks did he orshe receive?combative and confessional TV talk shows,students often don’t have any idea of what itmeans to talk productively and creativelytogether. You can help them have a better idea ofwhat a good literature discussion is if you letthem experience one. Select a thought-provokingshort story or poem for students to read, andthen choose a small group to model a discussionof the work for the class.In good discussions, you will often hearstudents say the following:Explain to participating students that theobjective of the discussion is to explore the textthoroughly and learn from one another.Emphasize that it takes time to learn how tohave a good discussion, and that the firstdiscussion may not achieve everything they hopeit will. Duplicate a copy of the LiteratureDiscussion Evaluation Sheet for each student.Go over the helpful and unhelpful contributionsshown on it. Instruct students to fill out the sheetas they watch the model discussion. Then havethe group of students hold its discussion whilethe rest of the class observes. Try not to interruptor control the discussion and remind the studentaudience not to participate. It’s okay if thediscussion falters, as this is a learning experience.“I was wondering if anyone knew . . .”“I see what you are saying. That reminds me ofsomething that happened earlier in the book.”“What do you think?”“Did anyone notice on page 57 that . . .”“I disagree with you because . . .”“I agree with you because . . .”“This reminds me so much of when . . .”“Do you think this could mean . . .”“I’m not sure I understand what you’re saying.Could you explain it a little more to me?”Allow 15–20 minutes for the discussion. Whenit is finished, ask each student in the group toreflect out loud about what worked and whatdidn’t. Then have the students who observedshare their impressions. What kinds ofcomments were helpful? How could the grouphave talked to each other more productively?You may want to let another group experiment“That reminds me of what you weresaying yesterday about . . .”“I just don’t understand this.”“I love the part that says . . .”“Here, let me read this paragraph. It’s anexample of what I’m talking about.”8Literature Circle Guide: The Cay Scholastic Teaching Resources

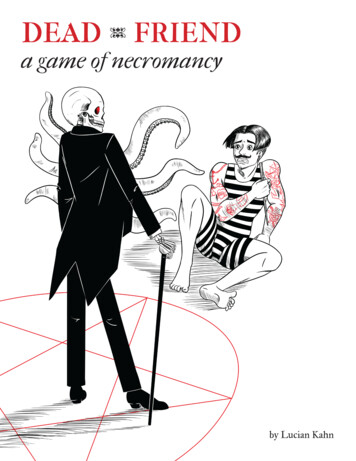

About The CayAdventure and real-life writing remainimportant parts of Theodore Taylor’s life andbooks. While on a tour of duty with the navalreserve during the Korean War, the author wasstationed in the Caribbean, where he providedhurricane relief to small islands. Here Taylor“sponged up the background and atmosphere”that led to The Cay.The Cay is a powerful book about survival andprejudice. While the novel keeps readers on theedges of their seats, it also raises questions aboutracism. Phillip, the young white boy in the story,mistreats Timothy, the black man with whom heis stranded on the island.Although Phillip’s racist attitudes changeduring the novel, critics view the author’smessage very differently. Some believe the bookattacks racism while others think it promotesracism because of the way Theodore Taylorportrays Timothy. Taylor says, “The Cay is notracist . . . and the character of Timothy . . . is‘heroic’ and not a stereotype.”The story idea for The Cay actually camefrom Taylor’s World War II research. He readan account about a small boy who was lost atsea after a German U-boat sank his ship. Phillip,The Cay’s main character, resembles one ofthe author’s childhood friends. Taylor recalls,“We had fun together but I remembered, lateron, his absolute hatred of black people. Man,woman, or child. Tragically, his mother taughthim that hatred.”Like his characters, many of Taylor’s storiesare drawn from real-life adventures he hasexperienced through various careers. He hasbeen a merchant marine, naval officer, sportswriter, boxer, screenwriter, and a producer anddirector of documentary films. Taylor says, “Ifind it hard to write about what I have not seenor, in some way, experienced. So I am alwaysready, anxious, and willing—at the sound of ajet engine turning on or the blast of a ship’swhistle—to go.”About the Author:Theodore TaylorGrowing up to be a writer was not one ofTheodore Taylor's childhood dreams. In fact,he stumbled into it. At the age of thirteen,Taylor received his first professional writingassignment, which was to write a highschool sports column for the local newspaper.Taylor remarks, “Never had I thought aboutwriting of any sort. And, to my knowledge, Ihad no talent for it. But I was certainly willing togamble that I could put a story together.”Other Books byTheodore TaylorThe Maldonado MiracleSince then Taylor has written more than fiftyfiction and nonfiction books for both childrenand adults. His love for the type of adventurefound in The Cay began when he was a child.He enjoyed roaming and exploring fields, muddycreeks, and salt marshes. For Taylor, booksbecame “an ‘extension’ of pretend adventures.”Often he would take as many as five adventurebooks home from the library.The Trouble with TuckWalking Up a RainbowSniperTuck TriumphantThe WeirdoTimothy of the CayBattle in the Arctic SeasA Shepherd Watches, a Shepherd Sings9Literature Circle Guide: The Cay Scholastic Teaching Resources

Enrichment: World War IIIn 1942, German U-boats began torpedoingtankers and boats in the Caribbean and along theeast coat of the United States at a horrifying rate.Between January and March, 216 ships, mostlyoil tankers, were sunk. By the end of sixmonths, 397 ships carrying over two milliontons of war materials had been sunk, and over5,000 people had died. In contrast, the Germansonly lost seven U-boats and 320 men. At thispoint, Germany was clearly winning the battle ofthe Atlantic.Today who would believe that the calm bluewaters of the Caribbean once exploded with gunfire and torpedoes? Yet during World War II, theCaribbean Sea, the setting for the Cay, was oneof the most important battlegrounds in the war.World War II began in September of 1939.Germany under Adolph Hitler’s rule, invadedPoland. When Germany wouldn’t pull its troopsout of Poland, England and France declared war.Other countries such as Canada, Australia, andIndia joined England and France in the war.These countries became known as the Allies.Italy and Japan sided with Germany; thesecountries were called the Axis powers. After theJapanese bombed United States military bases inHawaii, the United States entered the war on theside of the Allies.To fight back, the United States began using aconvoy system. Instead of sailing alone, groupsof cargo ships traveled together and were escorted by war ships. The convoys were successful,and shipyards in the U.S. increased their production of war ships.In addition to convoys, other strategies wereemployed to fight the U-boats. Radar and anunderwater detection device known as sonarwere used to find U-boats. From the skies, longrange aircraft began bombing the U-boats whenthey surfaced. Because of these massive efforts,the Allies successfully sank more boats thanGermany could produce. At last, the fiery battlesin the Caribbean and Atlantic subsided, andAllied ships could safely sail to their destinations.To survive during World War II, Englandneeded food and war materials from NorthAmerica. Curaçao, the Caribbean island in TheCay, produced gasoline and oil essential to thewar effort; large tankers transported theseproducts from the island across the AtlanticOcean to England. The greatest threat to theships sailing the Atlantic were Germansubmarines called Unterseeboote or U-boats.Phillip’s bone-chilling words at the beginning ofThe Cay accurately show how dangerous theseboats were.What kind of an impact do the GermanU-boats have on Phillip’s life? How doesWorld War II affect Phillip and his family?What happens to the S.S. Empire Tern?Like silent, hungry sharks that swim in thedarkness of the sea, the German submarinesarrived in the middle of the night.10Literature Circle Guide: The Cay Scholastic Teaching Resources

Enrichment: Coral ReefsMysterious, magical creatures inhabit the coralreef, which pulsates with life. Colorful clownfishhide inside the finger-like tentacles of theanemone. Plump-bodied butterfly fish weave inand out of brain and organ pipe coral while ahungry barracuda hovers nearby. As a bluewrasse approaches the barracuda, the predatoropens its mouth. Strangely, the barracuda doesnot devour the wrasse. Instead the wrasse cleansthe barracuda’s teeth just like a dental hygienist!Imagine an underwater fairyland ablaze withbrightly colored, strange-looking animals andplants that look like giant brains, thick fingers,and boulders. Welcome to the majestic world ofthe coral reef where life and action abound.Coral reefs cover over seventy million squaremiles of the ocean! They are the largeststructures ever built by animals, and the oldestreefs began growing over twenty-five millionyears ago. A haven for thousands of organisms,this ecosystem is one of the most diverseon Earth.Equally as magnificent and strange are thecorals, which are either hard or soft. Hard corals,the reef builders, are easy to picture becausetheir shapes resemble their names—elkhorn,leaf, star, brain, flower, doughnut, mountain, andlettuce corals.A tiny animal called a coral or a coral polypbuilds coral reefs. This minute, simple organismhas a jelly-like body that is enclosed in a tubethat opens at one end. Around its mouth aretentacles that the animal uses to gatherplankton, its food. These polyps extract calciumcarbonate from seawater and use it to form hardlimestone skeletons. When the polyp dies, itleaves behind this stony skeleton, which joinsmillions of other casings to form the coral reef.In contrast to hard corals, soft corals often looklike plants or quill pens. Soft corals include organpipe coral, umbrella coral, sea fans, and seapansies. Abundant on all reefs but particularly inthe Caribbean, the colorful red, violet, lavender,yellow, and ebony corals brilliantly shimmer likean artist’s palette floating in the sea.What is the relationship between the coral reef,the cay, and Devil’s Mouth? How does the coralreef on the east side of the island differ from theone on the north side? What kinds of reefanimals endanger Phillip?Coral reefs are located in a broad belt on bothsides of the equator. Ideal conditions for growthinclude clear, shallow, sunlit waters andtemperatures in the seventies. The Great BarrierReef, which is located off the coast of Australia,is the world’s largest reef. It is 500 feet high and1,260 miles long!11Literature Circle Guide: The Cay Scholastic Teaching Resources

Enrichment: CuraçaoCuraçao, a Caribbean island located offthe coast of Venezuela, is one of twogroups of islands known as theNetherlands Antilles group. Frequently,it is referred to as one of the ABCislands, along with its sister islandsAruba and Bonaire. The other group ofislands includes Saba, St. Eustatius, andSt. Martin.Spanish explorer Alonso de Ojedalanded on Curaçao’s coast in 1499 anddisco

Using the Literature Circle Guides in Your Classroom Each guide contains the following sections: A background information about the author and book A enrichment readings relevant to the book A Literature Response Journal reproducibles A Group Discussion reproducibles A Individual and group projects A Literatu