Transcription

Manual Therapy, Therapeutic Exercise,and HipTracTM for Patients with HipOsteoarthritis: A Case SeriesJohn M. Medeiros, PT, PhD1Tony Rocklin, PT, DPT, COMT2Pacific University, School of Physical Therapy, Hillsboro, ORTherapeutic Associates Physical Therapy, Portland, OR12ABSTRACTStudyDesign: Case series. Background:Manual, long-axis hip traction has been usedfor centuries to treat pain and dysfunctionassociated with hip osteoarthritis (OA). Thepurpose of this case series is to describe arehabilitation program that was used to treattwo patients with hip OA using the HipTractraction device in addition to manual therapyand therapeutic exercise. Case Description:Two patients were treated with manual therapy, therapeutic exercise, and administeredthe HipTrac device. The manual therapyand therapeutic exercise programs targetedimpairments each patient presented with ateach treatment session. The HipTrac, appliedin the clinic and in each patient’s home, wasused for mobilizing the joint capsule and toprovide pain relief. Outcomes: The primaryoutcome measures were the CareConnectionsFunctional Index (CCFI), the Visual AnalogPain Scale (VAS), range of motion (ROM),manual muscle tests, performance of functional single leg squats and single leg deadlifts. Improvements in all outcome measureswere observed for both patients. Discussion:Clinically meaningful improvements in selfreported function and pain were describedby both patients two years posttreatment.Both patients reported that they had greatlybenefited from combining the techniquesand procedures used. The use of the HipTracalong with traditional physical therapy procedures may relieve pain and improve function in patients with hip disorders.Key Words: mechanical traction, stiffness,gluteal muscle weaknessINTRODUCTIONFor decades, the first and most widelyused manual therapy technique for hip jointpain has been long-axis hip traction. Brackettstated in 1890, “the value of traction in thetreatment of the acute condition of hip disease has abundant evidence, both in its reliefof the symptoms and in its influence on thecourse of the disease.” Brackett credited Bradford and Conant for describing the positionof traction, that is, when the hip is flexed andabducted. Brackett concluded that in “ordinary cases” when continual traction is used,distraction occurs and “this may happeneven after disease has existed for some time.”Brackett also noted that continual tractionis beneficial for alleviating pain and for preventing the mechanical sequelae associatedwith excessive muscular irritability.1Many manual therapy techniques, including joint mobilization and manipulation,are important in the treatment of hip jointpathology. There is strong evidence in thecurrent literature that shows the benefit ofjoint mobilization, including long-axis traction, in improving range of motion (ROM)and functional index scores while decreasing pain. There has been much discussionabout how joint mobilization might affecthip joint pathology including (1) restoringpositional faults and accessory movements,2(2) stretching the joint capsule thus restoringnormal arthrokinematics, (3) inducing paininhibition and improving motor control,3(4) changing the descending pain inhibitorysystem and/or central pain processing mechanisms,4,5 (5) stimulating joint mechanoreceptors thus inhibiting nociceptive stimuli,6(6) altering inflammatory mediators,7 or (7)reducing fear avoidance with movement andexercise.8Long-axis traction is one of the techniques that can provide immediate pain reliefwhile also working to improve general mobility in the treatment of hip joint pathology.Based on recent clinical findings obtainedwith manual therapy and the potential needfor prolonged and continual traction asstated by Brackett, can we improve patientcare in the treatment of hip joint pathologyby combining these two concepts in the shortand long term?The purpose of this case series is todescribe a rehabilitation program thatincluded using long-axis hip traction usingthe HipTrac (MedRock Inc., Portland,OR) for two patients with hip osteoarthritis(OA). In addition to using the HipTrac, thepatients participated in an individually-dosedand impairment-specific manual therapy andtherapeutic exercise program. The HipTrac is123249 Guts Jan.indd 12a home medical device that the patient canuse independently to perform long-axis hiptraction that replicates the manual techniqueperformed in the clinic. It can be applied insupine in any degree of rotation and abduction as well as 4 levels of flexion (0 , 10 , 20 ,and 30 ). The HipTrac can also be used insidelying for traction in any degree of extension. The hip joint requires approximately400 N to achieve distraction5 and the HipTrac is able to produce forces well over 1000N. In this case series, the HipTrac was usedonly for supine long axis-traction in varyingpositions between close-packed and loosepacked hip positions. This is the first paperevaluating a multi-modal treatment approachto hip OA that allows the patient to receivelong periods of hip traction at home as wellas in the clinic.REVIEW OF THE LITERATUREWithin the last decade several authorshave investigated the effects of manualtherapy, including long-axis hip traction, asa component of the rehabilitation programfor patients with hip OA. In a single-blind,randomized clinical trial of 109 patientswith OA of the hip, Hoeksma et al9 reportedstatistically significant improvements inhip function (Harris Hip Score10) and pain(Visual Analog Scale [VAS]) in a group thatreceived manual therapy (which includedmanual traction of the hip) versus a groupthat received exercise alone.MacDonald et al11 described the outcomes from a series of 7 patients with hipOA who were treated with manual therapy(including long-axis hip traction) and exercise. All patients exhibited reductions in pain(numeric pain rating scale), increases in passive hip ROM, and improvements in function (Harris Hip Score10).Vaarbakken and Ljunggren12 comparedthe effectiveness of manual hip tractionthat was progressed to 800 N in 10 patients(experimental group) to a group (n 9) whoreceived exercises, soft tissue techniques, andself-stretch procedures. Six out of the 10subjects in the experimental group showedsuperior clinical posttreatment effects on theOrthopaedic Practice Vol. 29;1:1712/29/16 12:34 PM

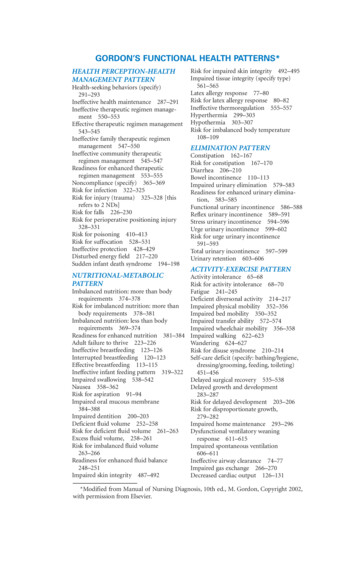

Hip Disability and Osteoarthritis Score13whereas none of the 9 subjects in the control group showed as comparable improvement on the same outcome measure. Theresults suggest that higher known forceswith manual hip traction are more effectivein reducing self-rated hip disability after 12weeks of treatment than the application ofunknown manual traction forces provided bythe clinician.Wright et al14 retrospectively analyzedthe data from 70 subjects who had participated in a randomized controlled trial. Fortyseven subjects were assigned to an exerciseand manual therapy group (which includedmanual hip traction) and 23 subjects wereassigned to a control group who receivedroutine care offered by their general practitioner. Significant differences in the regressioncoefficients for the Global Rating of ChangeScale15 and the pain scale from the WesternOntario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC)16 were found forthe exercise/manual therapy group versus thecontrol group.Using the WOMAC as the primary outcome measure, Abbott et al17 allocated 206adults with hip (n 93) or knee (n 113) OA tothe following groups: usual care only (n 51),usual care plus manual therapy (n 54), usualcare plus exercise therapy (n 51), and usualcare plus combined exercise therapy andmanual therapy (n 50). For the patients withno joint replacement surgery during the trial(n 162), the authors reported statisticallysignificant improvement in WOMAC scoresfor all 3 interventions; that is, manual physical therapy versus usual care, exercise therapyversus usual care, and the combined therapiesversus usual care. The manual therapy groupshowed the greatest reductions in WOMACscores of all groups overall and these reductions were still present one year later.Using a randomized participant and assessor-blinded protocol trial with a 12-weekintervention period, Bennell et al18 comparedmanual therapy, home exercises, education, and advice in 49 patients to a group ofpatients (n 53) who received a sham treatment intervention. All participants met thehip OA classification criteria of pain andradiographic changes set by the AmericanCollege of Rheumatology.19 The inclusion,criteria were as follows: 50 years of age orolder, pain in the hip or groin for more than3 months, a VAS score of 40 or higher on a100 mm scale and at least moderate difficultywith activities of daily living. Major exclusion criteria included participation in physical therapy/chiropractic treatment in the pastOrthopaedic Practice Vol. 29;1:173249 Guts Jan.indd 136 months, prescribed exercises for the hipor lumbar spine in the past 6 months, current participation in a daily walking programfor 30 minutes, or current participation in aregular structured exercise routine more thanonce weekly. The primary outcome measureswere the VAS and the WOMAC. After 10treatment sessions over 12 weeks, the investigators reported no significant differencebetween the treatment group and the shamtreatment intervention. Based on the resultsof their study, the investigators concludedthat “there is limited evidence supporting useof physical therapy for hip osteoarthritis.”CASE DESCRIPTION ANDOUTCOMESEach patient was informed that his physical therapy chart notes could be used in apublication or presentation. Each patientwas informed that his identity would not bedisclosed in a publication or presentation andfictitious names would be used.Patient OneJill is a 50-year-old female with a diagnosis of moderate right hip OA by herorthopaedic surgeon and supported by radiographic evidence. Her symptoms began 6.5months ago and she describes her pain assharp, dull, aching, throbbing, and constantin the groin and buttock regions. Her painis aggravated by sitting, rising from sitting,walking, ascending/descending stairs, andcrossing her legs. It is relieved by stretching,rest, and medication. She has been given therecommendation for total hip replacementat any time when she can no longer subjectively tolerate her pain and dysfunction. Jill’sCareConnections Functional Index (CCFI)score prior to receiving physical therapywas 52%. A change greater than 11 pointshas been reported as representing the minimal clinically important difference (MCID)for the lower extremity.20 Jill takes over-thecounter nonsteroidal anti-inflammatorymedications as needed. Jill rates her pain as 3out of 10 on the Visual Analog Pain Scale. AnMCID of 1.37 cm has been determined forthe 10 cm VAS.21 Jill’s ROM on intake anddischarge appears in Table 1.Jill had the following positive signs onthe right: Trendelenburg gait, flexion abduction external rotation (FABER) test, and acapsular pattern of restriction (defined hereas loss of closed-pack position, FABERs, andflexion/internal rotation quadrant). She hasincreased hip pain with compression anddecreased pain with traction. Jill’s manualmuscle test for sidelying hip abduction was4-/5 on the right and 4 /5 on the left. Jillcould not perform a functional single legsquat with gluteal emphasis or a single legdead lift without loss of balance, pelvic drop,or pain. The following goals and expectedoutcomes by time of discharge for her were asfollows: independence and compliance withher home exercise program, pain rated as 1out of 10 or less on the VAS, an increase inhip ROM (flexion to at least 110 , extensionto at least 15 , internal rotation to at least10 , and external rotation to at least 50 ), towalk safely and independently all distances,and to perform all normal work tasks without limitations.Jill received 17 physical therapy sessionsover a span of 6 months with therapy provided 2 times per week for 4 weeks, thenonce per week for 6 weeks, then one time permonth for 2 months, and finally 1 dischargevisit 2 months later. Manual therapy in theclinic was focused on improving hip jointmobility and decreasing pain. Techniques aredescribed in Appendix A. Home and clinictherapeutic exercise programs focused onincreasing lower extremity and lumbopelvicmobility, neuromuscular control, biomechanics, strength, flexibility and stabilization (Appendix B). The HipTrac was usedat home, after the eighth clinic visit, and tobe used between visits and after discharge forpain-control and to augment the hip mobility gains that she achieved with her clinicaltreatments (Appendix C – protocol).Jill’s CCIF increased from 52% (intakescore) to 86% (discharge score); this metthe MCID of 11 points. Jill’s VAS decreasedfrom 3 (intake score) to 0.4 (discharge score);this met the MCID criteria of 1.37 cm. Jillalso reported that her global rate of changewas 5/7 at discharge. Between intake anddischarge from physical therapy, Jill’s ROMretest scores for her right hip increased by 30 for flexion, 11 for extension, 7 for abduction, 18 for internal rotation, and 27 forexternal rotation (Table 1).When Jill was discharged, she reportedthat she rarely needed to take over-the-counter medications and was much more activenow, participating in yoga twice per week inaddition to her weekly home exercise program developed during treatment. Jill’s hipabduction manual muscle test at dischargewas 4 /5 on the right as compared to 4-/5 atintake. In addition, Jill was able to performfunctional single leg squats with glutealemphasis and single leg dead lifts withoutloss of balance, pelvic drop, or pain greatthan 1/10 (2 sets of 10 of each) at discharge.Jill reported that she felt that she had greatly1312/29/16 12:34 PM

Table 1. Jill’s Hip Range of Motion Over 17 Visits in a 6-month PeriodIntakeHip ROM on (prone, knee extended)9152025Abduction (supine)28403545Internal rotation (90 flexion)0191830External Rotation (90 flexion)35656273Flexion (supine knee flexed)benefitted from home manual therapy usingthe HipTrac as well as her home exerciseprogram. She verbalized understanding thather OA will progress and that consistenthome manual therapy and exercise may continue to help her have less pain, increasedmobility, and increased functionality. Shereports her new goal is to more comfortablydelay her surgery as long as possible. As ofcompletion of this case series two years later,she has yet to have surgery and reports thatshe continues to maintain her higher levelof function, reduced pain, and a more activelifestyle.Patient TwoTravis is a very active 40-year-old malewith a diagnosis of moderate left hip OA andleft femoral acetabular impingement (FAI)by his orthopaedic surgeon and supported byradiographic evidence. He reports his symptoms began two years before with a gradualonset, which he noticed while running. Hischief complaint is a dull and constant ache inthe left groin, thigh, and buttocks. Walking,stairs, and recreational sports such as running,skiing, cycling, hiking, and surfing aggravateTravis’ symptoms; he reports that nothingrelieves his symptoms. He has been given therecommendation for total hip replacement.Travis’ CCIF score on intake was 80%. Achange of greater than or equal to 11 pointshas been reported as representing the MCIDfor the lower extremity.20 Travis takes overthe-counter nonsteroidal anti-inflammatorymedications as needed. Travis rates his painas 3.7 on the VAS. An MCID of 1.37 cm orgreater has been determined for the 10 cmVAS.21 Travis’ ROM on intake and dischargeappears in Table 2.At intake Travis had a positive leftTrendelenburg gait, positive FABER test,and significant capsular restrictions. Hehad increased pain with compression anddecreased pain with traction. His hip abduc-tion muscle strength was 4/5 on the left and4 /5 on the right. Travis could not performa functional single leg squat with glutealemphasis or a single leg dead lift without lossof balance, pelvic drop, or pain.Expected goals and outcomes for Traviswere as follows: home exercise programindependence, pain rated as 1/10 or less onthe VAS, improved hip ROM (flexion to atleast 110 and internal rotation at 90 of hipflexion to at least 10 ), and participation inmost of his recreational/sports activities withdecreased symptoms less than 1/10.Travis received 15 physical therapy visitsover a 5.5 month period with therapy provided 2x per week for 4 weeks, then 1x perweek for 4 weeks, followed by 3 visits overthe next 4 months. Manual therapy in theclinic focused on improving hip joint mobility and decreasing pain through a varietyof techniques (Appendix A). Home andclinic therapeutic exercise programs focusedon increasing lower extremity and lumbopelvic mobility, neuromuscular control,biomechanics, strength, flexibility, and stabilization (Appendix B). HipTrac was initiated at home, after the fourth visit, to beused between visits and after discharge forpain control and to supplement, reinforce,and further improve the hip mobility gainsthat he achieved with his clinical treatment(Appendix C – protocol).Travis’ CCFI score increased from 80%(intake) to 94% (discharge); this met theMCID of 11 points. Travis’ VAS decreasedfrom 3.7 (intake score) to 1 (discharge score);this met the MCID criteria of 1.37 cm. Hisperceived global rate of change was 5/7 atdischarge. Between intake and dischargefrom physical therapy, Travis’ ROM retestscores for his left hip increased by 27 forflexion and 14 for internal rotation (Table2). Travis’ left hip abduction manual muscletest score at discharge was 4 /5 as compared to 4/5 at intake. In addition, Travis143249 Guts Jan.indd 14was able to perform 3 sets of 10 functionalsingle leg squats and single leg dead lifts withproper technique and no pain over a 1/10 atdischarge.Near the end of Travis’ physical therapyprogram, he reported that he had participated in a painfree 62-mile bike ride. He alsostated he was very happy to not only delay histotal hip replacement but participate in moreactivities with less pain. He was able to returnto surfing with some symptoms and couldride his bike daily for commuting withoutaggravating his hip. Against the advice of hismedical team, he also returned to running 4to 5 miles on trails 3 times per week with painbelow a 2/10. Because of his interest in regular participation in the high-level activities ofsurfing, running, and performance cycling,Travis reports that he has good days anddays with some soreness. However, he nowhas improved mobility and strength in addition to pain management strategies to copewith any flare-ups. He reports that he can usethe HipTrac and home exercise program toquickly decrease pain from increased activityand maintain hip mobility. He reported thathe would not have been able to return to anyof these activities or delay hip surgery for thepast two years if he had not used the HipTracregularly at home.DISCUSSIONProviding individually dosed and impairment-specific manual therapy, therapeuticexercise, a home exercise program, and useof traction using the HipTrac independentlyat home between visits and after dischargeincreased the quality of life for these twopatients. Hip traction has long been established as an effective therapy for patients withhip OA.1 The most effective form of long-axistraction is when the distraction force is progressed.12 The HipTrac allows the patient toreceive prolonged and progressed distractionforces in the clinic and at home.We have described a multi-modal rehabilitation program that produced subjectiveand objective results for these two patients.Our results are consistent with otherauthors9,11,12,14,17 who have reported benefitsfrom manual therapy, exercise therapy, anda reinforcing home program. However, ourfindings are not supported by the work ofBennell et al.18 Differences between our caseseries and the Bennell et al18 study may berelated to the following: (1) the dosage ofmanual therapy and therapeutic exercise provided; (2) the impairment-specific manualtherapy techniques and therapeutic exercises provided to each individual patient orOrthopaedic Practice Vol. 29;1:1712/29/16 12:34 PM

Table 2. Travis’ Hip Range of Motion over 15 Visits in a 5.5-month PeriodIntakeHip ROM (deg)DischargeRightLeftRightLeftFlexion (supine knee flexed)11585120112Extension (prone, knee extended)22202320Abduction (supine)35404045Internal rotation (90 flexion)2802714External Rotation (90 flexion)40504551lack thereof and, (3) the activity level of thepatients.Regarding dosage, the authors of thispaper spent more time with the patients thandid Bennell et al.18 The authors believe thatwhen treating such a complicated and varying pathology, a meaningful dose of manualtherapy and therapeutic exercise cannot beproperly applied in only 30 minutes andonly one time per week. Some individualsmay only need 30 minutes while others mayrequire up to 60 minutes per session, withsessions being 1 to 2 times per week for 4 to6 weeks initially.Regarding the manual therapy and exercise approach, the authors’s program wasindividualized for each patient whereas thatof Bennell et al18 used a semi-standardizedapproach to treatment. Random allocation ofsubjects into treatment and control groups isa very important component of a well-donestudy, as was the case with the Bennell et al18work. However, treatment for hip OA mayneed to be very specific to the individual’simpairments, and providers may need totake special care to non-randomly categorize patients into the proper treatment protocol in order to show success. For example,clinical reasoning would discourage placing apatient with very good ROM into a manualtherapy-emphasized category to increaseROM, just as we would not expect to place apatient with severe capsular restrictions intoan exercise-only category. Treatment emphasis and categorization should depend on thatindividual’s impairments.In addition, all of the Bennell et al18subjects received only 2 to 3 different jointmobilization techniques: long-axis distraction in clinic and lateral distraction and/orinferior glide in hip flexion. Only 22% of thesubjects in their active group also receivedjoint mobilization in anterior glides for hipextension and external rotation, and 16%received posterior glides for internal rotation.Orthopaedic Practice Vol. 29;1:173249 Guts Jan.indd 15It is well established that hip extension, internal rotation, and external rotation can begreatly limited with hip OA and are criticalto specifically target in treatment when theselimitations exist. In our case series, our twosubjects received 8 different joint mobilization techniques, as needed, rather than only2 to 5 techniques to specifically target eachindividual’s impairments.Also, Bennell et al18 excluded patientsunder 50 years old as well as patients whocould walk continuously for more than 30minutes daily and those who participated inregular structured exercise more than onceweekly. By excluding these individuals, Bennell et al18 may only be studying individualswho are unmotivated to exercise/improve,who are in too much pain or dysfunctionto exercise, or who are fear-based individuals avoiding exercise. There is also a growingnumber of individuals younger than 50 yearsold that may benefit from treatment for hipOA earlier in the disease cycle. We believethat all individuals of all ages along the continuum of mild, moderate, and severe OAwho are active and inactive more accuratelyrepresent those who need and may seek treatment for hip OA prior to becoming surgicalcandidates.Evidence-informed practice takes intoaccount what has been published in the literature, the experience of the clinician, and thegoals of the patient. Consequently, successmay need to be individually defined. Thereis no cure for hip OA and therefore providerscannot rid these patients of OA. The goalsfor most patients are to more comfortablyavoid or delay surgery, improve mobility,decrease risk for co-morbidities due to inactivity related to their disease, decrease pain,and increase overall quality of life to engagein all of their social, occupational, and leisure activities. For some patients, making achange from a 7/10 pain level and no participation in a regular exercise regimen toa 3/10 pain level with consistent participation in an exercise regimen could equate to100% success. For others, success could beto delay their hip replacement by 6 monthsfor personal scheduling reasons while nothaving increased risk for hypertension orloss of blood glucose control due to inactivity. However, for all patients, we should notunderestimate the significance of assistingthem to become more active for at least 30minutes per day to decrease the risk for heartdisease, stroke, cancer, diabetes, depression,and other co-morbidities related to inactivity. Total hip replacement is the gold standard of care once conservative measures havebeen exhausted and it is well documentedthat these individuals do very well after surgery in terms of functionality and quality oflife. However, surgery is expensive, carries itsown risks associated with being under general anesthesia, and will usually need to berepeated 15 to 20 years later on the same hip.From the point of view of the patient as wellas that of the federal and private health caresystem, it is in the best interest to more comfortably delay this surgery as long as possibleto decrease the overall health care utilizationrelated to chronic pain and inactivity whileimproving the quality of the life for eachindividual.We would like to emphasize the importance of evidence-based treatments includingclinic and home manual therapy, therapeuticexercise, and patient education that can helpeach individual meet his or her specific goals.In this process we hope to discover whichmanual therapy techniques and therapeuticexercises, as well as which dosages of each,can help improve outcomes for individualsalong the entire progressive continuum ofhip OA and other hip joint pathologies.Our two patients had joint mobilityrestrictions, muscle length deficits, musclestrength limitations, and insufficient muscleendurance/coordination at intake. The twopatients were gradually progressed to higherlevels of clinical manual therapy, traction athome via HipTrac, therapeutic exercise, andsoft-tissue stretch-and-release techniquessuch that the rehabilitation remained challenging. Our case study added home manualtherapy, in the form of long-axis tractionwith HipTrac, as an additional benefit for thepatients between visits and after discharge.One potential challenge with using HipTrac is that it may be cost-prohibitive forsome patients. According to their website,cost to rent is 125 per month and the cost topurchase is 895. Additionally, since this is anew device, there is no literature on standard-1512/29/16 12:34 PM

ized protocols for use and progression. Thesetwo patients were not required to follow anystrict protocol. They were simply educated inloose-packed and close-packed positions andwere encouraged to progress towards closepacked as quickly as was comfortable. Inaddition, they were encouraged to discover aparticular position, intensity, and dosage thatproduced personal results for them in theform of decreased pain, increased mobility,and improved functionality during activitiesof daily living.A limitation of any case series is that causality cannot be inferred from the data, especially with only two subjects and no controlgroup. However, the findings can be usedto inform clinical practice. Future studieswill need a more robust experimental designand the addition of a control group. Theseauthors would like to see further studies onthe effectiveness of this device. Studies couldspecifically address reductions in medicationusage, increases in activity level, decreases inpain scores, increases in ROM, and increasesin functional indices among patients withhip OA. The unique role of this device inindependent home programs including therapeutic exercise and home manual therapyneeds further study.CONCLUSIONWe have shown that providing manualtherapy, exercise therapy, a home program,and home long-axis hip traction with theHipTrac provided clinically importantimprovements in pain and function for ourtwo patients with OA of the hip. While notdefinitive, we also documented objective andsubjective feedback indicating that the use ofcontinuous and progressive hip traction canplay a valuable role in improving mobilityand function while relieving pain in patientswho have hip OA.REFERENCES1.2.3.Brackett EG. An experimental study ofdistraction of the hip-joint. Boston MedSurg J. 1890;122(11):241-244.Vicenzino B, Paungmali A, Teys P. Mulligan’s mobilization-with-movement,positional faults and pain relief: currentconcepts from a critical review of literature. Man Ther. 2007;12(2):98-108.Hing W, Hall T, Rivett D, VicenzinoB, Mulligan B. The Mulligan Concept ofManual Therapy–Textbook of Techniques.Atlanta, GA: Elsevier; 2015.4.5.6.7.8.9.10.11.12.13.Paungmali A. O’Leary S, Souvlis T,Vicenzino B. Naloxone fails to antagonize initial hypoalgesic effect of amanual therapy treatment for lateralepicondyalgia. J Manip Physiol Ther.2004;27(3):180-185.Sterling M, Vicenzino B. Pain andsensory system impairments that may beamenable to mobilization with movement. In: Vicenzino B, Hing W, RivettD, Hall T, eds. Mobilisation with movement: the art and the science. Atlanta,GA: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier;2011:86-92.Paungmali A, O’Leary S, Souvlis T,Vicenzino B. Hypoalgesic and sympathoexcitatory effects of mobilization withmovement for lateral epicondylalgia. PhysTher. 2003;83(4):374-383.Sambajon VV, Cillo JE Jr, Gassner RJ,Buckley MJ. The effects of mechanical strain on synovial fibroblasts. J OralMaxillofac Surg. 2003;61(6):707-712.Vicenzino B, Hall T, Hing W, Rivett D.A new proposed model of the mechanisms of action of mobilization withmovement. In: Vicenzino B, Hall T

Manual Therapy, Therapeutic Exercise, and HipTracTM for Patients with Hip Osteoarthritis: A Case Series 1Pacific University, School of Physical erapy, Hillsboro, OR 2 erapeutic Associates Physical erapy, Portland, OR John M. Medeiros, PT, PhD1 Tony Rocklin, PT,