Transcription

Lessons from Venturing Out of the Ivory TowerLee CooperUCLA Anderson School of ManagementVN PNEW VENTURE PRESSSANTA MONICA, CALIFORNIA

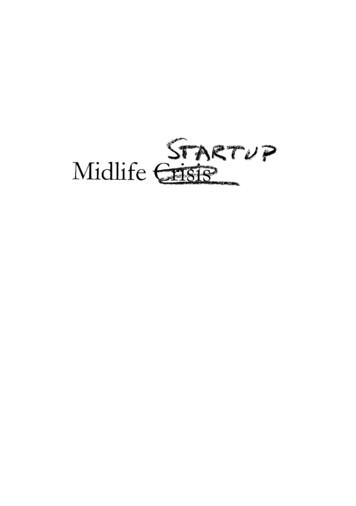

Library of Congress Control Number: 2003116638Cooper, Lee G. 1944–Midlife Crisis Startup: Lessons from Venturing Out of theIvory Tower / Lee Cooperp.cm.Includes bibliographical references and index.ISBN 0-9748554-0-5 (Hardcover)1. New-venture initiation.2. Entrepreneurship.3. Technology-enabled marketing. 4. Technology transfer.First EditionCopyright 2004 by Lee CooperAll rights reserved.Printed in the United States of AmericaNo part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in orintroduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or byany means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, orotherwise), without the prior permission of the publisher. Requestsfor permission should be directed to:permissions@NewVenturesPress.comor mailed to:PermissionsNEW VENTURE PRESS1158 26th Street, Suite 336Santa Monica, CA 90403

vTable of ContentsTable of Contents . vList of Figures.viiList of Tables .viiiPreface . ixAcknowledgements. xiPART I.LOGIC IN USE. 11. Birth of a Notion . 31.1Surfin’ . 31.2July 28, 2000. 52. Foreplay.132.1The Conceptual Models.142.2A Dynamic Framework for Strategic Marketing Planning222.3Into the Turbulent Field .223. “The Best Business Plan I Ever Read”.253.1Building a Team .403.2Dealing with UCLA.513.3The First “Public” Business Plan .553.4The First Meeting of the Board of Directors .574. I Should Have Read Charles Ferguson.614.1Whitewater Canoeing .614.2Return to the Real World.664.3Irrational Exuberance.724.4Due Diligence.744.5The Seeds of Conflict.774.6The Heart of Darkness .854.7All Work Is Voluntary.955. Smart Money.1015.1The Series-A Negotiations.1015.2The Prelude to Series B.1055.3Don’t Even Think About a Down Round.1145.4Last Chance for Strategy.1215.5D is for Doom.1295.6Kiretsu Versus Portfolio .1365.7The Tale of DVX.138

5.8E is for Epilogue .141PART II. RECONSTRUCTED LOGIC .1496. A Linear Path.1516.1Introduction to the Linear Path.1516.2Kernel Analysis: Aligning Innovations with Markets .1526.2.1 Finding the Kernel .1576.2.2 Market Finding .1606.3The Value of the Entrepreneurial Vision .1646.4Writing a Business Plan.1666.5Due Diligence on the Business Plan .1897. Strategic Maps.1937.1Strategy as Comprehensive Problem Solving .1937.2Articulating the Critical Issues .1997.2.1 Political Issues:.1997.2.2 Behavioral Issues .2067.2.3 Economic Issues.2077.2.4 Sociological Issues.2097.2.5 Technological Issues .2097.2.6 The Key Decision.2107.3Mapping the Critical Issues .2107.4Valuation .2137.5Plans Must Be Dynamic.2137.6What If?.2257.7Strategic Planning Using the Four Risks .2278. Meta Lessons .2378.1The Legend of Quincy Thomas.2378.2Sharing the Map .2398.3The University and Faculty Entrepreneurs .2448.4The Regulating Tension of Opposites.2548.5A Place to Begin and a Path to Make It Better.2588.6What’s Next? .259References .261Index .269

viiList of FiguresFigure 5.1. The Mental Map of Factors Affecting SDC’s Success .121Figure 5.2. “Bake-Off Results (Static Simulator).132Figure 6.1. The Drug-Discovery Market .162Figure 6.2. PersonalClerk’s Communication with the Client Network.173Figure 6.3. PersonalClerk Utilizes a Variety of Data Sources toProvide Real-time Marketing Messages .174Figure 6.4. Competitive Customer Analysis Technologies. .179Figure 6.5. Organization Chart.186Figure 6.6. Engagement Structure .187Figure 7.1. Critical Issues Map. .195Figure 7.2. Potential Competitors and Features .199Figure 7.3. The Mental Map of Factors Affecting SDC’s Success .211Figure 7.4. Prototype for a Strategic Map .231Figure 7.6. The Factors Impacting Market Risk.232Figure 7.7. The Factors Impacting Human Risk .233Figure 7.8. Factors Impacting Capital Risk. .234Figure 7.9. The Complete Strategic Map for CMSS .234

List of TablesTable 6.1. Financial Forecast Detail – Planned Forecast .184Table 6.2. Financial Forecast Detail – Limited Forecast.185Table 7.1. Likelihood of States in Parent Nodes.215Table 7.2. Two-Way Conditional Likelihoods. .216Table 7.3. Three-Way Conditional Likelihoods.219Table 7.4. Four-Way Conditional Likelihoods.220Table 7.5. Five-Way Conditional Likelihoods.220Table 7.6. Six-Way Conditional Likelihoods.223Table 7.7. Comparative Valuations Under Different Scenarios.226Table 7.8. Critical Issues Facing CMSS.230

ixPrefaceA young scientist’s first lesson in scientific writing is to distinguishthe flow of actions that describe the record of scientific behaviorduring an inquiry from the reconstruction of that record that formsthe framework for a journal article. The flow of actions is called Logicin Use and the reorganization of that flow into the typicalIntroduction, Methods, Results, and Discussion breakdown is calledReconstructed Logic.Part I of this book relates the flow of experiences I had mainlybetween the summer of 1999 and the beginning of 2002 inconceiving, creating, financing, and building a company to dotechnology-enabled marketing – the kind of service that personalizesthe interaction of Internet users with Web merchants. Innovators,particularly university faculty or other mid-career professionals, whowish to move their ideas toward commercialization need to recognizethe sometimes-subtle signs of problems or pitfalls while engaged inthe incessant rush of a startup experience. But they need more thanthat. And thus, I have included a second part to this book thatconsiders the steps in the startup process from a more detached,reconstructed view.The second part deals in particular with business-plan writing andplanning a business. These are not the same thing. One writes abusiness plan for specific reasons to specific audiences. This is thetopic of Chapter 6. The resulting document is temporal and static.“Cut and paste” makes it easier to come up with the next document,but that one, too, is static. Planning a business requires a dynamicframework that addresses simultaneously the complex set ofproblems the business faces. Chapter 7 takes on that task, with aparticular focus on university-based innovation. Chapter 8summarizes the overarching lessons and issues I believeentrepreneurs and innovators need to consider before and during thenew-venture process.

xiAcknowledgementsI greatly appreciate the support the Price Institute provided todevelop this book and the course on “Strategic Marketing Planningfor New Ventures.” This support was augmented by the Price Centerfor Entrepreneurial Studies at UCLA and a grant from the AcademicSenate at UCLA. Intel Corporation helped start me on this path withits funding (1996-99) of Project Action that allowed me to thinkseriously about what it means to bring radically new products tomarket. I wish to thank all of these funding agencies for theirsupport. Prof. Al Osborne, then director of the Price Center forEntrepreneurial Studies at the Anderson School, UCLA, providedencouragement and support throughout this project. Thanks.I benefited from the comments on early drafts by many colleagues atUCLA and elsewhere, particularly Steve Mayer, Marshall Goldsmith,Jack McDonough, Carolyn Cressy Wells, Ed Muller, Sam Culbert,and Alan Andreasen. Thank you for your insights andencouragement. Bill Broesamle and Gerard Rossy provided veryvaluable insights on drafts of the manuscript. Thanks to Fred Fox forhelping me realize some of the complexities of the UC PatentAgreement and the California Labor Code. I also thank Dan Gordonfor his careful reading of the manuscript, and suggestions to make it amore accessible document for its audience. I thank Jeff Marx forencouraging me to explore more deeply into the personal andemotional side of this experience, and for his valuable feedback onthat side of the tale.In Chapter 7 I have relied on parts of a planning project submitted byRavi Narasimhan, Al Mamdani, Vijay Mididaddi, and Pak-yan (Eric)Liang for the Winter 2000 section of “Marketing Strategy in theDigital Economy.” I thank them for allowing me to adapt theirefforts. Ravi Narasimhan read the draft of this chapter and madethoughtful suggestions. I have used parts of a planning projectconcerning Core Micro-Solution Systems by Benjamin Chow, PeterJanda, Julie McDonald, Luciano Oliveira, Glenn Oyoung, and Arthur

Wang, from the Spring Quarter 2003 offering of “Strategic MarketingPlanning for New Ventures.” I also want to thank Sandra Fox ofHigh-Tech Business Decisions, Inc. for providing a study of highthroughput screening. Professor C.J. Kim, Wayne Liu, and PatrickDeguzman played integral parts in helping the students and meunderstand the technology and preparing the strategic plan.I want to thank each and every one of the friends and colleagues whohelped me with the new venture described in this book. They took anentrepreneurial leap-of-faith with me for which I am deeply grateful.Their great skill and commitment made this the most uniqueadventure of my professional life. I have changed most namesbecause, despite the personal sound and themes of the writing, it isnot about them, nor is it about me. It is about recognizing, amid therush of activities associated with any startup, the signals that say topush ahead, and the signals that say stop and think.And finally I thank my wife, Ann, who has been there through it all,as a constant source of love, encouragement, and tolerance. I willnever forget.Lee CooperSanta Monica, September 2003

1PART I.LOGIC IN USE.

2 Midlife Crisis Startup

1. Birth of a Notion 31.Birth of a Notion1.1Surfin’Experienced entrepreneurs tell you to be prepared for the emotionalroller coaster that launching a new venture entails. I think this evokesthe wrong image. A roller coaster has a fixed track. You can see whenyou are climbing to the peak or diving into a valley, and you can seethe bottom. You are also strapped in, and insurance companies havesigned off on the risk. Your path is precisely the same as that of manywho have gone before and will come after. Starting a new venture isnothing like that.Surfing is a more apt metaphor. Before you even get wet you canwatch how the waves break, look for submerged obstacles, and waxyour board to minimize slipping. For the most part, you can chooseyour wave from how its early form looks. You can see which way thewave is breaking, and opt to go left or right on the wave. You canchoose whether to kick out – if the wave walls up, cut back and letthe wave reform– or ride through. The experience of a good ride ona strong wave is exhilarating, but you can also wipe out. A badchoice, or just a bad break, can send you flying into a storm of whitewater, crushing you under its weight – leaving you unsure of whichway is up and whether you will get there in time for another breathbefore being sent down again. No two waves or rides are the same.The uncertainty inherent in surfing parallels the new-venture process.Sometimes great rides are abundant and sometimes the waters areflat. Waves come in sets, as do entrepreneurial opportunities. The keyis to recognize the opportunity in the early stages – when the wave isforming – ride the curl while the break is good, and kick out beforethe shore pound crashes you to the bottom. Easier said than done.I hung up my homemade surfboard many years ago, when thefamous storm surf of Christmas 1962 brought 30-foot waves toMalaga Cove in Palos Verdes. I watched from the bluff as veteran

4 Midlife Crisis Startupsurfers Greg Knoll and others rode these massive forces of nature. Iknew I didn’t have the skill or bravura to join them. The next biggestwave I saw was almost four decades later, when the digital revolutionand the Internet craze built toward a crest. I jumped on the mythicalseventh wave of the seventh set. It was quite a ride. I tried torecapture the thinking that went on during the experience, thefeelings both good and bad, and the emotional texture from clarityand joy to confusion and anger. For the feelings and emotions, thewriting has to stand on its own. I hope I have been revealing enoughto prepare you to encounter some of the vicissitudes I faced. I ameager to share the thinking that took place during the ride this bookdescribes. I hope it aids understanding the process of new-ventureinitiation, particularly for university-based technology, in whichradical innovations can change the way we live in and experience theworld. Ultimately, this is a story about the tension between a world oftechnological genius and a world of business. The masters of theseworlds don’t know how to talk to each other. Yet, so much of themagnificent prospects for our future depend on this communication.I think managers need to extend their thinking at least enough intothe technology that the basis for decision making is not opaque. Andthe technological geniuses of this world need to understand that,while others may be the best judges of the practicality of markets andopportunities, they more than anyone else are the best judges of thetechnological limits of their innovations.I start in the middle of the ride, with the story of the first live test ofthe new technology, before rewinding to the beginnings of 0012/1/19998/1/199910/1/19996/1/19991100

1. Birth of a Notion 51.2July 28, 2000Jason Kapp picked me up at 8 a.m. from my Santa Monica home fora 9 a.m. meeting at Idealab Capital Partners, the Pasadena-basedInternet incubator that spawned eToys, CarsDirect, Cooking.com,Overture, and others. Jason, our VP of client services, had played akey role in helping me start this venture. We had pitched ourapproach to technology-enabled marketing many times before in oursuccessful 5 million B Round. We knew the story: The Internetdangled the prospect of huge potential returns for those who couldmonetize its promise for personalized shopping and browsing. Butthe preparation this time was different. We had heard exaggeratedrumors about successes in our arena by one of Idealab’s portfoliocompanies, as well as tales of their acumen at taking other people’sideas. So the focus centered on what to reveal and what to concealabout our approach. But the dark presence in the car, and over alldiscussions for almost a month, concerned when we would launchour first real market test – a test that would determine the near-termfate of this startup.Through the B-Round representative on our board, we had arrangedwith iPlayer.com to purchase 20 million banner-ad impressionsdesignated for registered users on its popular Internet versions ofvideo games. We would use our segmentation method to learn aboutthe preferences within each segment of its customers; we hoped touse that machine learning to increase the abysmal (and getting worse)click-through rates on the company’s banner ads. Using the site’sown customer data to improve ad targeting fulfilled the marketingmaxim to know your customers and circumvented all the privacy issuesconcerning public-policy makers at the time. June 15 was set as thestarting date. At .75 per thousand, 15,000 to get a live test of theextension of our personalization technology in the Internet ad spaceseemed like a good idea. When the planned test failed to start ontime, Scott Sellers, the VP for business development at iPlayer.com,told us that June inventory was sold out at 5 CPM (cost perthousand) – a much higher rate than we had negotiated. We arrangedto start July 1 at 2.50 CPM, and waited and waited some more.Two VA-Linux machines with our software had been co-locatedwithin the test site’s Web-server racks at Exodus. We had two similarmachines in our own half rack at PSINet in Marina del Rey, and fourmore tied to a T-1 line at our office in Santa Monica. Tests on ourend were fine so far, but within iPlayer.com’s network we couldn’t

6 Midlife Crisis Startupread the cookie – that tiny piece of text code that gives theoriginating site so much information about the customer at the otherend. We needed the site to change six lines of code to share cookiesjust within its complete subnet. Since my technical expertise coverednot cookie logic but the conceptual and analytical models that droveour learning and optimization algorithms, I was barely grasping ontothese problem areas. Early in July, the client’s CTO promised tomake the simple change we required, but it didn’t happen. On July19, the CTO left for a year, supposedly to recover from anunspecified illness. I suspected burnout. It was July 25 before Sellersgot his team to put the new cookie code in place. We found and fixeda small bug in our database agent, and sent a ready-to-go message toSellers. Ravi Srinivasan, the head of our technical-implementationteam and an Anderson MBA student, heard that AdForce, the firmserving iPlayer.com’s ads at that time, had been notified to startsending our ads first thing on July 27 and still we waited.Jason and I agreed to show Idealab much the same demo that hadbeen developed in record time for our first board of directorsmeeting in early February. The demo featured our productrecommendation suite, called PersonalClerk, that incorporated theInternet advertising optimization only as a simple, natural extensionof the personalization solution. We wouldn’t talk about the ad testwith Idealab.The 45-minute meeting went nowhere, but went nowhere smoothly.We learned Idealab’s efforts were mostly vapor – great customerdata, but no sense that the company knew how to use it effectively.Technology-enabled marketing operates at the boundary betweenintelligent information systems and that obscure area called marketingscience. Without strong capabilities in both areas, the problems are atbest half solved and the solutions, consequently, are half-baked.Once back in the car I called Ravi. He sadly reported, “No data yet.”Then I heard Chuck Yu, our hardware guru, in the backgroundyelling that the first ads were being sent. It was 9:52 a.m. and ourlabor pains had just begun. The drive back felt like a rush to thehospital to be in time for the delivery of my first child.When Jason and I arrived back at the bullpen on the second floor,where most of the technology group sat, everyone was gatheredaround Chuck’s desk. One window on his Linux notebook tracked

1. Birth of a Notion 7the number of open sockets – one for each active user. The theorywas that when a user’s browser requested a page, our HTTP agentthat handled the raw traffic opened a socket as a file description,delivered an ad, sent the needed information to our learningalgorithm and a session log, and closed the socket. We watched as thenumber of open sockets increased toward 1,024, blocking the threadand crashing our system. Our design didn’t threaten to bring downthe client site or interfere with its basic operation, but when oursystem crashed, the ads we paid for weren’t being delivered. The datathat were crucial to our machine-learning algorithms weren’t beingcollected. Chuck’s fingers flew over the keyboard each time thethread was blocked. If the sockets were unblocked (closed) when theprocess crashed, a simple chain of commands would restart theprocess immediately. If the sockets remained open – blocked fromaccepting a new-user request -- Chuck had to reboot our Linux boxinside the client’s rack at Exodus before restarting the process. Thenlearning would begin again, until the next blockage.Why was this happening? What could we do about it? I didn’t have aclue. Chuck was madly typing away to keep our downtime to aminimum, and I had no insight into the problems we faced. Thirtyyears of designing and building medium- and large-scale analyticaland statistical systems for squeezing meaning out of market data, andI had never been this clueless. Others had done major chunks ofmany of my earlier projects, sometimes for efficiency and sometimesfor learning. When stumbling blocks were encountered, I had alwaysbeen there to solve the problem. Not this time. After more than threedecades on the faculty of UCLA’s management school, I was nowoutside the ivory tower. I needed to step back, micro-manage less,and grant other people control over a problem-solving process thattranscended my expertise.The intellectual resources available were substantial, but incomplete.Giovanni Giuffrida, a UCLA doctoral candidate in intelligentinformation systems, was our CTO, and had developed wonderfullyinto a leader of the technology group. An ever-reshuffling handful ofprogram developers would gather around the conference table in hisoffice next to the bullpen while Giovanni worked with them throughwhatever was the greatest barrier to our technical progress. Giovanniand I previously had worked together for several years on large-scale

8 Midlife Crisis Startupforecasting projects1 and research-oriented datamining projects thathad led to the first datamining article published in the mainstreammanagement literature.2 Our big-data experience mostly concernedretail scanner records. We had to deal with about 25 million recordsat a time and be prepared to create up to 800 million forecasts a year.Those are very small numbers compared to what we faced on theWeb.Our main Web expert, Fabrizio diMauro, an amazing code hacker,was stuck on a trans-Atlantic flight returning from Italy – andgrounded in Newfoundland when his girlfriend became extremely illin flight. When Giovanni, Jason, David VanArsdale (VP/admin) andI had started this venture together, Fabrizio was the first person hiredin the technology group. Giuseppe Blanco, a Web-design specialist, Cprogrammer, and the third part of the Sicilian Connection, was in thebullpen. Not only did these three grow up in the same small town inSicily, they all reconnected in computer-science graduate programs atUCLA. Brandon Davinski, the UCLA computer-science undergradwho worked with us full time in the summer, brought an almost scaryknowledge of Web programming. He already had found a majorsecurity hole in another client’s cash-register program. He couldchange the price for anything in his or anybody’s current shoppingbasket. Many times I mumbled to myself that I was glad Davinskiwas on our side. Wesley Rhim was a database expert with deep SQLand Perl skills. Murilo, a great C programmer with a PhD in physics,had just started earlier that week. Nick, a computer-science undergradfrom MIT, worked with us that summer. So did Jonathan, the bestcomputer mind in my older son’s cohort (then 20), who hadprogrammed the common object module (COM) needed for dealingwith the Microsoft servers that the client used. In supporting roleswere a group of very talented college students in their first importantsummer jobs.At first, the core technology team tried to force the sockets to close –fix the symptom and ignore the problem. We didn’t find a way to dothis. Maybe the level of simultaneous traffic was too heavy for only1,024 sockets, but this seemed unlikely given the short duration1Cooper, Lee G., Penny Baron, Wayne Levy, Michael Swisher, and Paris Gogos(1999), “PromoCast: A New Forecasting Method for Promotion Planning,”Marketing Science, 18, 3, 301-316.2Cooper, Lee G. and Giovanni Giuffrida (2000), “Turning Datamining into aManagement Science Tool,” Management Science, 46, 2 (February), 249-264.

1. Birth of a Notion 9(milliseconds) that each request required. So Giuseppe and Jonathanpulled a 10-thread version of the HTTP agent from the programrepository and tested it. Chuck copied it over to the machines atExodus, compiled it – keeping the other system going to the lastsecond -- and then started the 10-thread code. The inexorable rise inblocked sockets foretold the outcome. Blocked sockets led to crashedthreads. It took 10 times as long to crash the whole program, but thistry eliminated traffic volume as the possible cause. To eliminatebandwidth issues, the banner ads were copied over to the extramachines at PSINet and served from there. No discernibledifference.By mid-afternoon, someone suggested that possibly old or strangebrowsers contributed to the problem. Our session logs were full ofrequests from newer Internet Explorer and Netscape browsers, butnone from the much older versions of these or from WebTVbrowsers. Jonathan grabbed a WebTV emulator that we used to loginto iPlayer.com. No ad was delivered and no record of the usershowed up in the session log. This signaled that the problem was inhow our HTTP agent handled old or odd browsers. The HTTP agentwas our interface to Internet traffic – in essence, a Web-serveroperating system stripped down for speed. We could handle about1,200 requests per second, per box in a system we knew how to easilyparallelize, if additional speed was needed for high-volumecommercial sites. But apparently, too much of the browser handlinghad been stripped out. The fix required putting a whole APACHEWeb-server operating system in front of our HTTP agent to takeover the browser handling. Giovanni understood the best talents ofhis core team and assigned David and Jonathan to the APACHEtasks,

roller coaster that launching a new venture entails. I think this evokes the wrong image. A roller coaster has a fixed track. You can see when you are climbing to the peak or diving into a valley, and you can see the bottom. You are also strapped in, and insurance companies have signed off on