Transcription

The Heartof the KingdomChristian theology and childrenwho live in povertyEdited by Angus RitchieA better childhood. For every child.www.childrenssociety.org.uk

PrefaceTim ThorntonThis collection of essays is an invitation.It is an invitation to the church to joinwith The Children’s Society in a process oftheological reflection that will challenge howwe understand and respond – both practicallyand prayerfully – to the issue of child povertyin the UK. It is certainly not an attempt by TheChildren’s Society to articulate a theology onbehalf of the church, or even to suggest thatwe know what the theological answers are. Itis simply an invitation for others to join us in aconversation that we hope will help us all seethe issue more clearly.The origins of this collection lie in aconsultation at St George’s House in Windsor,hosted by The Children’s Society in 2011 incollaboration with the Contextual TheologyCentre, where we began to outline whata theological response to child povertymight encompass. It has continued throughnumerous conversations and a roundtablewhere we have tried to listen to diverse voiceswithin the wider church in the UK.Over the course of its gestation, the topic ofthis collection of essays has become moreand more relevant, its urgency only increasingas it has become clear not only that thegovernment would fail to achieve its targetsfor the reduction of child poverty, but alsothat levels of child poverty are rising and willcontinue to do so for the foreseeable future.2The Heart of the KingdomIn this context much of the public debate hasfallen into practical issues about definitionsof child poverty or divisive political splitsbetween right and left over whetherirresponsible parents or reduced levels ofwelfare spending are more to blame. Whathas been less in evidence in the public debateis a vision of what we as a society wantfor our children and what, in light of thatvision, are the vocations of families, churchesand the state. For the church, these moreprofound questions are properly the territoryof theology, and we hope this collection willprove to be a useful place to start in discerningsome of those theological answers and fillingin a space in the public rhetoric.In reading these essays I invite you to joinin the theological debate and in particular Iwould encourage you to consider the place ofhope, a theological virtue in which we are allinvited to live and yet often and increasinglyseems to be in short supply.Each of the essays in this collection representsthe views of its author or authors and notnecessarily the views of The Children’s Society.We offer them in the hope that they will starta conversation that will ultimately inform ourpractical work with children, our campaigningand advocacy, and our prayer and liturgicalresources.We would like you to be a part of thatconversation.

ContentsIntroduction4(Angus Ritchie)Part 1: Testimony5Poverty and the experience of children (Tess Ridge)The impact of child poverty on future life chances (Jonathan Bradshaw)Hidden poverty: refugee and migrant families in the UK (Ilona Pinter)71014Part 2: Theological reflections19Does charity begin at home? (Angus Ritchie and Sabina Alkire)The Gospel, poverty and the ‘lordship of the poor’ (Michael Ipgrave)What a Christian view of society says about poverty (John Milbank)Six theological theses on the family and poverty (Krish Kandiah)Child poverty and the vocation of government (Angus Ritchie)2125283237Part 3: Practical responses41Responding to child poverty: a parish storyFrom reflection to action (Matthew Reed)(Andy Walton and Adam e Heart of the Kingdom3

IntroductionAngus RitchieJesus places children and the poor at theheart of the Kingdom of God. He tells us thatwhen we offer hospitality and care to childrenand those who lack food or shelter, we arewelcoming and caring for him (Matthew18:5, 25.34–40). Indeed, he teaches that theKingdom of God belongs to the poor, and thatwe can only enter it when we ‘become likechildren’ (Matthew 18:1-3, Luke 6:20).For all the economic difficulties of recentyears, Britain remains one of the mostprosperous nations on earth. Our persistentfailure to translate this national wealth intowell-being for our children is a spiritual andmoral scandal. It reveals something deeplytroubling about our hearts and our priorities –and how far our earthly kingdom remains fromthe Kingdom of God.The Heart of the Kingdom has been writtento help Christians address the issue of childpoverty. The collection is divided into threeparts:1. The first section describes the currentcontext, and in particular the way childrenand young people experience poverty.These essays leave us in no doubt aboutthe seriousness of the current situation andthe yawning gap between political rhetoricabout ‘compassion’ and ‘social justice’, andthe lives of many British children.2. The second section offers a series oftheological reflections. The authors drawon a wide range of Christian traditions,from evangelical Protestantism to CatholicSocial Teaching. They explore the waysin which churches are called to respondto child poverty and relate this to thecomplementary vocations of family,community and government.4The Heart of the Kingdom3. The final part of the collection consists oftwo practical responses, one very local(through the lens of a parish in east London)and one national (from the Chief Executiveof The Children’s Society). They are offeredas part of the invitation to readers to join anongoing process of reflection and action –helping each of us consider our response tothe theology and testimony presented in thepreceding essays.I am grateful to all who have been part ofthe process of discussion and reflection thathas led to this collection – and in particularto the authors of these essays, to my othercolleagues at the Contextual Theology Centre(especially Caitlin Burbridge and Josh Harris),to Nigel Varndell, Lily Caprani, Sam Roystonand Kate Tuckett at The Children’s Societyand to Anthony Clarke, Sue Coleman and PaulRegan who have offered very helpful advice.All too often, theology has been seen as apurely academic discipline; the preserve ofa small elite of privileged experts with littlepractical relevance. Theology which is faithfulto the Gospel could hardly be more different.The purpose of this book, as of all suchtheology, is not merely to inform. It is to helpeach of God’s children to share more deeplyin his life and love.The Feast of the Divine Compassion,7 June 2013

Part 1:TestimonyThe Heart of the Kingdom5

Children are not simply to be understood andvalued as adults-to-be. Their childhood is ofvalue in its own right, and it offers us a uniqueand crucial window onto the Kingdom ofGod. For this reason, our collection of essaysbegins with an essay by Tess Ridge, whoseresearch gives voice to children and youngpeople, as they describe the experienceof living with poverty. Jonathan Bradshawdemonstrates that child poverty also has aprofound impact on their future life chances.Indeed, his contribution shows how childpoverty impoverishes us all – economically aswell as spiritually.6The Heart of the KingdomThe final essay in the section, like the others,seeks to bring children’s poverty morefully into the public eye, and to challengethe growing tendency to stigmatise andstereotype those in greatest need. Thepoverty of children in migrant and refugeefamilies is often the most hidden. It is crowdedout by an increasingly shrill and intense medianarrative about ‘scroungers’ and ‘benefittourists’. Ilona Pinter speaks to us of a realitywhich is radically at odds with this narrative.She demonstrates how far the treatment offamilies seeking sanctuary in Britain fallsshort of the biblical vision of hospitality tothe ‘stranger’ who is in need. In doing so, shebegins to address the question that all threeessays raise: What is a faithful and effectiveChristian response to the suffering of childrenwho live in poverty?

Part 1: TestimonyPoverty and the experienceof childrenTess RidgeIn this short essay, I want to share with youfindings from my research - conducted overa number of years with children and youngpeople who were living in low-income familiesin the UK. In consequence, all of the effectsof poverty shared in this paper are based onchildren’s own accounts of their lives and ofthe issues that concern them. My research,and that of others in the field, shows that theimpact of poverty can be felt across all areasof children’s lives, affecting their economicwell-being, their mental and physical health,their social relationships and the opportunitiesand choices open to them. A recent review of10 years of research with low-income childrenfound that:‘ the experience of poverty in childhoodpoverty are both pervasive and disruptive.Poverty permeates every facet ofchildren’s lives from economic and materialdisadvantages, through social andrelational constraints and exclusions, tothe personal and more hidden aspects ofpoverty associated with shame, sadness1If we look at each of these in turn, it is possibleto get some sense of the everyday challengesthat face children at school, at home and intheir neighbourhoods. To be impoverishedin an essentially affluent society is a veryparticular and stigmatised experience andchildren are very well aware of this.Money and ‘going without’Children experience the realities of theireconomic world within their families, butthey are also exposed to different economicrealities through interactions with their peersand through their engagement with thewider world and the media. For children inlow-income families, financial resources andmaterial goods are in short supply. Childrenare extremely anxious about the adequacyof income coming in to their homes andwhether there is enough for them and theirfamily’s needs. They also often lack importantchildhood possessions, like toys, bicyclesand games. When toys and bikes break, theystay broken and are not replaced. Poverty inchildhood also brings a lack of everyday itemsthat we take for granted, like food, towels,bedding and clothing. Children in urbanareas can experience run-down, degradedand degrading environments that are poorlyserved by services, shops and public transport.However, low-income children in rural areascan equally find themselves isolated andmarginalised within their small villages andtowns, and experience a severe lack of socialopportunities and activities, compounded byexpensive and inadequate public transport.2Children who are poor experience greatuncertainty about whether or not they are ableto gain access to sufficient funds to go outwith their friends and share in their activities.Childhood has its own social and culturaldemands, and the need to stay connected withpeer-group trends and fashions is a significantsocial issue for children. Most low-incomechildren do not receive any regular pocketmoney, so paid work is often the answer,working at part-time jobs between schoolhours and at weekends. Many children showgreat resourcefulness in accessing work andattempting to alleviate their disadvantage;they also show considerable understandingof their family’s financial situation. In someThe Heart of the Kingdom7

families, children help out directly with moneyor contribute towards their own needs.However, paid work is often in tension withschool work, and money gained is rarelysufficient to sustain them adequately in theaccepted culture of their peers. So manychildren just ‘go without’, moderating theirneeds to ensure that they do not put pressureon their families.‘Well I don’t like asking Mum for money thatmuch so I try not to. Just don’t really askabout it. It’s not that I’m scared it’s justthat I feel bad for wanting it. I don’t know,sounds stupid, but, like sometimes I save upmy school dinner money and I don’t eat atschool and then I can save it up and havemore money. Don’t tell her that!’ Courtney3Friendships and social networksFriendships are important for children, notjust in terms of the growth and developmentof social skills and social identity, but also inlearning to understand and accept others.Low-income children, like others, reallyvalue friends; they play an important rolein safeguarding children from isolation andbullying. But many low-income childrenhave been bullied at some point and thiscan have a marked effect on how they feelabout their schools and in some cases, aboutthemselves. As well as the fears and realitiesof experiencing bullying, many childrenexperience difficulties in making and sustainingfriendships. Transport costs and participationcosts all conspire to leave children feelingexcluded from many of the social and leisureexperiences that their more affluent peerstake for granted. Reciprocity is damaged;if you have very little home space, a coldand/or damp home, or no private transport,it is difficult to enter into sharing lifts andsleepovers, for example. Simple things thatadults may not perceive as important oftenaffect children’s relationships, such as clothingexpectations and taking part in shared leisureactivities. Having the right clothes is animportant badge of belonging and childrenoften express a high degree of anxiety aboutmaintaining their social status against theperils of being seen as different or ‘poor’.8The Heart of the Kingdom‘You can’t do as much and I don’t like myclothes and that. So I don’t really get to domuch or do stuff like my friends are doing.I’m worried about what people will think ofme, like they think I am sad [pathetic] orsomething.’ Nicole4Given children’s evident fears of experiencingstigma and difference associated withpoverty and disadvantage, the significance ofopportunities to develop and keep strong andsupportive social networks is clear.Children’s social lives at schoolSchool is important for children academicallybut also socially. It is within the schoolenvironment that children meet with a widerand more diverse group of their peers thanthey would in their home and neighbourhoods.But children’s accounts of their school livesindicate that they experience considerabledisadvantage within their schools, with manyreporting feeling bullied, isolated and left outof activities and opportunities at school. Theirfears about being seen as different and beingleft out are made worse by the knowledgethat other children are doing more and havingmore, creating insecurity and uncertainty forsome children.‘They go into town and go swimming andthat, and they play football and they go toother places and I can’t go. because someof them cost money and that.’ Martin5Children like Martin tend to exclude themselvesfrom school activities. Disillusioned with theprocess, they do not take the letters homewhich ask for money for school trips and otheractivities because they know their parentswould not be able to afford them. Otherfactors within schools also act to compoundthe economic and social disadvantages thatchildren experience. Economic barriers, such asfees for school trips and the costs of academicmaterials, are made worse by institutionalprocesses: demanding examination criteria, aninsistence on school uniforms, deadlines forpayments towards extracurricular school tripsand activities that give little leeway for parentswho cannot pay on time. There are also

Part 1: Testimonymeetings after school with no transport homeand stigmatising bureaucratic processes in thequalification and delivery of welfare support,such as free school meals. So what low-incomechildren identify – when we listen to them – arenot the dangers of being excluded from schoolbut rather the dangers of being excludedwithin school.Life at home with family and friendsIn talking about their lives at home and intheir communities, children often highlighttheir inner worries and their fears of socialdifference and stigma. Their experiences ofpoverty affect their self-esteem, confidenceand personal security. These are difficultareas for children to reflect on, as difficultieswith friendships and worries about socialacceptance can be particularly hard forchildren to articulate. However, children arekeenly aware of the impact of poverty on theirlives and on the lives of their parents.‘I worry about my mum and if she’s likeunhappy and stuff like that. SometimesI worry about if we haven’t got enoughmoney, I worry about that.’ Carrie6Children’s fears of social detachment andsocial difference are very real, and they areoften acutely sensitive to the dangers of beingexcluded from the activities of their friendsand social groups. They are also uncertainand fearful about their futures, and these aredifficult burdens to carry in childhood.‘I worry about what life will be like whenI’m older because I’m kind of scared ofgrowing older, but if you know what is infront of you then it’s a bit better, butI don’t know.’ Kim7Children are clearly struggling to protect theirparents from the realities of the social andemotional costs of childhood poverty on theirlives. This can take many forms: self-denial ofneeds and wants, moderation of demands andself-exclusion from social activities, schooltrips and activities. In some cases parents maybe aware of their children’s strategies andreluctantly accept them in the face of severelyconstrained alternatives. In others children areregulating their needs more covertly.Final thoughtsOur understanding and perceptions of childrenwho are poor are often ill-informed andstereotyped. Children’s lives are very diverse,and poor children are not a homogeneousgroup. Their experiences of poverty will bemediated by many other factors includinggender, disability, ethnicity and age. Childrenin different circumstances will have their ownexperiences and concerns to relate, and theirown perceptions of how poverty has affectedtheir lives. For many children, poverty comesinto their lives close on the heels of otherdifficult and often painful situations. Thiscould be the onset of sickness and disability,unemployment, family dissolution, asylumseeking, upheaval and change. This meansthat the experience of poverty is closelyentwined with other difficult life events thatchildren have to mediate, make sense of andnegotiate. But it is clear from talking withchildren that they actively engage with theirlife circumstances, developing ways and meansof participating where and when they canthrough work and play. The personal and socialrepercussions of poverty for children are oftenoverlooked and easily disregarded, especiallywhen policy concerns are focused on other(perhaps more tangible) concerns such aschildren’s school attendance and performance,their health and their future employability asadults. But being seen as a ‘poor’ child in anaffluent society, where poverty is associatedwith stigma and shame, can be a painful anddamaging experience. Low-income childrenare not passive victims of poverty; they arestruggling to maintain social acceptance andsocial inclusion within the cultural demands ofchildhood, but it is a struggle that is definedand circumscribed by the material and socialrealities of their lives.The Heart of the Kingdom9

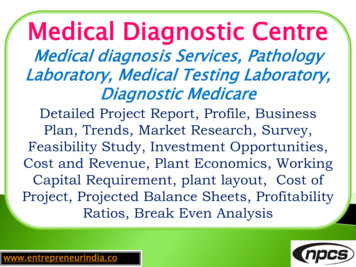

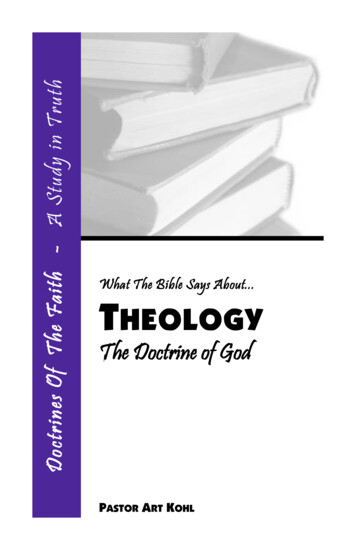

The impact of child povertyon future life chancesJonathan BradshawIntroductionA major criticism of past research on childpoverty is that it has focused too much onwell-becoming rather than well-being – on theimpact of poverty on life in adulthood ratherthan in childhood. So I would have preferredto have been asked to write the previous essayrather than this one – that is to write (again)about the impact of child poverty on wellbeing in childhood!8From both the perspective of theology andof contemporary human rights discourse, thewell-being of children during their childhoodis what really matters. Children are oftencalled the ‘church of tomorrow’ – but in fact,they are of course part of the church of today,and as such the wider community has a dutyof nurture and care. Children have rights aschildren, not just as adults-to-be, and this isrightly the focus of the UN Charter on theRights of a Child.Yet the impact of poverty in childhood onfuture life chances is important from a socialand economic perspective (in addition to thetheological arguments) in three main ways.1. If poverty in childhood leads to a lesshealthy, productive and happy adulthood,this is an additional reason for dealingwith the injustice of child poverty. It isanother reason why poverty is not fairfor the individual.2. If poverty in childhood is associated withpoor outcomes in adulthood, it harms us all.Or rather – if we can convince tax payersthat it is not good for them to allow childpoverty to continue, we have a greaterchance of tackling it in childhood.10The Heart of the Kingdom3. Connected to this, it may be that many ofthe problems of society – ill-health, lowskills, crime, squalor, unhappiness – are soclosely associated with child poverty thatit is really no good tackling them directlyby, for example, spending more on healthservices, improving schools and colleges, orincreasing spending on crime prevention.The best way to tackle these problems isthrough tackling the underlying cause:child poverty.Governments already accept these argumentsand take action. Indeed this is why childpoverty is such a salient preoccupation ofsocial policy analysts – it is the best indicatorwe have of government failure. Of coursegovernments act with more or less success.Figure 1 shows what the child poverty rates inEU countries would be without any transfersfrom the government, and what the childpoverty rates are after transfers are made.The countries are ranked by the impact oftransfers. Thus Greece reduces its pre-transferchild poverty by 18%. The UK does not do toobadly, reducing its own by 58%. But we are notnearly as effective as Norway, which reduceschild poverty by 71%.

Part 1: TestimonyFigure 1: League table of child poverty( 60% median threshold) reduction in the EU 2011960807050405040303020% reduction602010100before transfersafter transfersSo what do we know about the impact ofchild poverty on future life chances? There isa vast literature which has fairly recently beenreviewed by Griggs and Walker.10 Their reviewcovered: Health: The impact of poverty on healthduring the antenatal period, birth and infancyis profound. This is the period of foetaldevelopment that has great significancefor later health, cognitive development,educational attainment and thus employmentand earnings potential. There is evidencethat poverty is associated with lower ratesof breast-feeding, earlier births, low birthweight, and higher rates of mortality,morbidity and maternal depression. Thesehave knock-on effects in childhood health:poverty is associated with school absencesdue to infectious illnesses, obesity, anaemia,diabetes, asthma, poor dental health, higherrates of accidents and accidental deaths,and physical abuse. Poor children also haveless access to health services. Poverty isassociated with poor and overcrowdedhousing conditions with poor garyUnited KingdomSwedenGermanyLuxemburgCyprusFranceCzech RepublicSloveniaLithuaniaCroatiaBelgiumEuropean andsMaltaRomaniaBulgariaPortugalItalySpainGreece0% reductionoutcomes. Poverty is also associated withpoor health behaviours, especially higherrates of maternal smoking. It is also stronglyassociated with poor mental health. Thesehealth experiences in childhood lead to poorhealth outcomes in adulthood and old age,including the worst levels of cardio-vascularproblems, diabetes and heart disease. Hirsch11has estimated the health costs of childpoverty in the UK to be 500 million peryear. Education: There is a large body of evidencelinking poverty to poor educationaloutcomes, much of it associated withdifficulties in cognitive development ininfancy. But other factors include limitedaccess to high-quality pre-school provision,the poverty of schools in deprived areas,and economic constraints on participatingin school activities. Children on free schoolmeals are less likely to meet Key Stagestandards and achieve five or more goodGCEs, to stay on at school or enter tertiaryeducation. Low levels of skill achievementhas a knock-on effect in employment,The Heart of the Kingdom11

resulting in high levels of young people whoare not in education, employment or training(NEET), and long-term unemployment –which in turn is associated with crime andsubstance abuse. The life-time costs of NEEThave been estimated at 15 billion ( 7 billionin resource costs and 8.1 billion in publicfinance costs.12 Special educational provisionalso costs 3.6 billion per year. Employment: There is a strong relationshipbetween growing up in poverty andlabour market participation and progress.The relationship between poverty andworklessness persists even if education iscontrolled for. Lower educational attainmentis associated with low skills and thus lowerpaid jobs. Unemployment is inefficient,resulting in lost productivity and tax, andextra benefit payments.The Griggs and Walker review went on toinclude a discussion of the impact of childpoverty on behaviour, family and personalrelationships, and subjective well-being. There ismuch debate about the association of povertyand many outcomes. Does child poverty causecrime? There is evidence from the USA thatit does, but little evidence in the UK. Earlyparenting is associated with child poverty andearly parenting is associated with the earlyparenting of the children. Is early parenting acause or consequence of child poverty? Beingbrought up in a lone parent family is a causeand consequence of child poverty and thereis some evidence that outcomes in education,employment, early partnering and future familystability are worse for children who experiencelone parenthood. However no one has reallybeen able to answer the question – is this dueto lone parenthood or the poverty associatedwith it? The evidence suggests that povertyand parental conflict are more likely than familystructure to be the cause of these outcomes.Much of the evidence on the associations ofchild poverty and future life chances comesfrom longitudinal studies, in particular thebirth cohort surveys. There is also evidencefrom spatial analysis of local areas with highproportions of poor children (as measured bythe proportion of children in receipt of meanstested benefits) also having lower levels ofemployment, worse health, lower educationalparticipation, more crime and worse housingand environments.1312The Heart of the KingdomAs we have seen, one way these outcomes canbe measured is by estimating their economiccosts. Blanden and colleagues14 used the 1970British Birth Cohort survey to estimate theearnings loss at age 26, 29/30 and 34. Theyestimated that growing up in child povertyreduced earnings by 15–28% and the chancesof being in employment by 4–7%. Most of thepenalty was due to low skills. If child povertyhad been abolished it would have generatedan extra 1–1.8% of GDP from increasedproductivity, increased tax revenue andreduced benefit payments.As part of the same research programme forthe Joseph Rowntree Foundation, Bramley andWatkins15 estimated the public services costsof child poverty including the personal socialservices, the health services, school education,police and criminal justice, housing, fire andsafety, area based programmes and localenvironmental services. Their total estimatefor 2006/7 was between 11.6 billion and 20.7 billion.The Joseph Rowntree Foundation concluded16that child poverty costs the UK at least 25billion a year, including 17 billion that couldaccrue to the Exchequer if child povertywere eradicated. Moving all families abovethe poverty line would not instantly producethis sum, but in the long term, huge amountswould be saved from not having to pick upthe pieces of child poverty and associatedsocial ills.‘The moral case for eradicating childpoverty rests on the immense humancost of allowing children to grow updeprivations and unable to participate fullyin society. But child poverty is also costlyto everyone in Britain, not just those whoexperience it directly.’17Is it really poverty or parenting? There is nodoubt that some children who grow up inpoverty do very well in later life. Also there isrecent evidence from the Millennium CohortSurvey that improving parenting behaviour andattitudes, and reducing maternal depressioncan mitigate the worst development outcomesof persistently poor children.18 Poverty hindersgood parenting, but positive parenting has

Part 1: Testimonybeen estimated to mitigate only about half theimpact of poverty on children’s achievement inthe first year of school.19 Parenting matters atall levels of living. Poverty matters to the poorbut affects all of us.potential, more families and communitieswill prosper and the UK will succeed. Thiswhy it is in everyone’s interest to play theirrole in eradicating child poverty.’20Between 1999 and 2010, child poverty fellas a consequence of government effortsto eradicate child poverty. The result wasan improvement in child well-being in alldomains. UNICEF found that the UK movedfrom the bottom to the middle of the OECDleague table on child well-being.21 Now livingstandards are falling. Unemployment is high.Cuts in benefits and services have beenloaded onto families with children. Benefitsthat mitigate the impact of poverty are forthe first time since the 1930s being upratedby less than inflation. Absolute child povertyis increasing. This is a tragedy for the childrenaffected, very bad for their futures, and forsociety as a whole.The Heart of the Kingdom13

Hidden poverty: refugee andmigrant families in the UKIlona Pinter*‘Suppose an outsider lives with you in your land. Then do not treat him badly. Treathim as if he were one of your own people. Love him as you love yourself. Rememberthat all of you were outsiders in Egypt. I am the Lord your God.’ (Leviticus 19:33–34)‘

The Gospel, poverty and the ‘lordship of the poor’ (Michael Ipgrave) 25 What a Christian view of society says about poverty (John Milbank) 28 Six theological theses on the family and poverty (Krish Kandiah) 32 Child poverty and the vocation of gov