Transcription

READING FLUENCY INTERVENTIONS FOR MIDDLESCHOOL STUDENTS WITH ACADEMIC AND BEHAVIORALDISABILITIESA m a n d a S t r o n g H il s m ie rSamford UniversityJ o s e ph H. W e h b yK a t h e r in e B. F a l kVanderbilt UniversityAbstractThe research base on how to effectively intervene to improve thereading fluency of students with academic and behavioral disabilitiesat the middle school level does not provide a strong support for evidence-based practices with this age group. The purpose of this studywas to extend the body of research on reading fluency interventionsto impact the reading fluency and reading motivation of students withacademic and behavioral disabilities at the middle school level. Thisstudy investigated (a) the effectiveness of a repeated reading and oralpreviewing fluency intervention on the reading rate and accuracyscores of middle school students with academic and behavioral disabilities and (b) the additive effect of a contingent reinforcement andperformance feedback intervention combined with this antecedent intervention. A multiple baseline design across 4 students was used todetermine the effect of the intervention. Participants exhibited growthover baseline reading performance.As academic standards rise, the need forstudents at the secondary level to be proficientreaders is greatly evidenced. Unfortunately,only 34% of high school seniors are proficientreaders, while only 28% of eighth gradersand 34% o f twelfth graders read on gradelevel (National Education Goals Panel, 1995).Proficient readers experience reading successearly. This reading success leads to greatertext exposure and more reading opportunities, which further improves these students’overall reading ability. Struggling readersexperience early reading failure resulting inless text exposure and fewer opportunities toread causing these students’ to fall further andfurther behind their peers. This phenomenonis evidenced by the fact that the majority ofstudents who exhibit reading problems inthe third grade will continue to struggle withreading for the rest of their lives (Bruhn, &Watt, 2012; Gunter, Coutinho, & Cade, 2002;Lyon, 1995)The reading difficulties of struggling readers is even more alarming given the assumption that students at the secondary level areable to read and comprehend content area materials that range from a ninth grade readinglevel to the third year of college (Biancarosa53

54 / Reading Improvement& Snow, 2004;; Santa, 2006). The absenceo f reading instruction at the middle and highschool level results in the continued distancebetween students with reading difficulties andtheir peers (Biancarosa & Snow, 2004; Harris, Marchand-M artella & Martella, 2000;).Due to the expectation that students at thesecondary level are reading proficiently, littledirection has been provided for teachers atthis level on effective methods o f teachingreading and the most effective instructionaltools for meeting the reading needs o f struggling students (Joseph & Schisler, 2009).Relationship between Reading Deficits andBehavior ProblemsAdding to the issues associated with secondary students’ reading difficulties is thenoted occurrence o f behavioral issues seen instudents who are struggling readers (Bruhn& Watt, 2012; Oakes, Mathur, & Lane, 2010;Wang & Algozzine, 2011). The relationship between reading deficits and behaviorproblems has been well documented in theliterature (Anderson, Kutash, & Duchnowski,2001; McIntosh, Sadler, & Brown, 2012;).Research has documented the comorbidity ofreading and behavioral deficits that can become increasingly worse over time (Andersonet al., 2001; Benner, Allor, & Mooney, 2008;McIntosh et al., 2012).Importance of Reading FluencyReading fluency is an important milestonein the development o f independent readers.Fluency has been defined as the ability to readwords accurately and quickly with minimalemphasis on the mechanics o f text (Meyer &Felton, 1999; Strecker, Roser, & Martinez,1998). Fluent readers are able to automatically decode words and concentrate on grasping the details o f what is being read (Chard,Vaughn, & Tyler, 2002; Homan, Klesius, &Hite, 1993) while reading text quickly, accurately, and with meaning.A strong relationship exists between fluencyand overall reading ability (Fuchs, Fuchs, Hosp,& Jenkins, 2001; Morgan, Sideris, & Hua,2012;). As students increase the speed and accuracy with which they read; students are ableto access more difficult text and demonstrate increased reading comprehension (Levy, Abello,& Lysychuk, 1997; Young & Bowers, 1995).Homan et al. (1993) reported that students whoexhibit difficulties in reading comprehensionalso demonstrate lower levels o f fluent reading.Schwanenflugel, Hamilton, Kuhn, Wisenbaker, and Stahl (2004) determined that decodingspeed is a major factor in developing prosodicreading and improved reading comprehension.Students who are able to decode words fasterexhibit greater fluent reading skills, allowingthem to comprehend text rather than focus onthe reading o f isolated words.Fluency Interventions for Students withDisabilities in the Middle School GradesWhen reviewing the research on middleschool reading interventions found effectivefor students with academic and behavioraldisabilities, minimal research was found specifically focuses on this area (Lewis-Lancaster& Reisener, 2013; Mansett-Williamson &Nelson, 2005; Mercer, Campbell, Miller, Mercer, & Lane, 2000; Morris & Gaffney, 2011;Strong, Wehby, Falk, & Lane, 2004; Wanzek,Vaughn, Roberts, & Fletcher, 2011). O f thesix studies focused on students with academicand behavioral disabilities, three examined anoverall reading intervention with a supplemental fluency additions (Mansett-Wilhamson &Nelson, 2005; Strong et al., 2004; Wanzek etal, 2011) and three focused on a specific reading fluency intervention to improve rate andaccuracy (Lewis-Lancaster & Reisener, 2013;Mercer et al., 2000; Morris & Gaffney, 2011).The results from these studies were mixed, butshowed promise for intervening with an agegroup o f students who appear to have beenoverlooked in the research literature.

Reading Fluency Interventions for Middle School Students / 55Purpose of the StudySettingThe purposes o f this study are (a) to determine the effectiveness o f a repeated reading and oral previewing fluency interventionon the reading rate and accuracy scores ofmiddle school students with academic andbehavioral disabilities and (b) to determinethe additive effect of a contingent reinforcement and performance feedback interventioncombined with this antecedent intervention.This study extends the research in improvingthe reading fluency of middle school studentswith academic and behavioral disabilities byincluding the use o f nonrelated text as a dependent variable.The intervention was conducted inoutside of the students’ classroom with aresearch assistant (RA) trained on how toimplement the intervention and administerthe dependent measures. The areas included a small room outside the participants’classroom and a comer of the gymnasiumwhen students were not present. Minimalinterruptions occurred during the baselineand intervention session, and students wereredirected if an interruption occurred. Theintervention was provided as a supplementto the reading instruction received in theclassroom. The reading instmction providedin the classroom was the district-mandatedLanguage! program (Greene; 1998). Language! is a literacy intervention programdesigned for students in grades 1-12. Thisprogram is designed to prepare students toreturn to the regular curricula by advancingtheir reading skills from where they are currently functioning to their expected gradelevel performance. The school district hadmandated the Language! program be usedwith all students in Grades K-8, and all theteachers in the school had attended a 3-daytraining on how to implement the readingprogram in their classrooms.MethodParticipantsParticipants in this study were identifiedwith a Specific Learning Disability (SLD) orOther Health Impairment- Attention DeficitHyperactivity Disorder (OHI-ADHD). Fourstudents in grades 6 through 8 were identifiedto participate in this study. Table 1 providesan overall subject description of the studentsin the study. All participants in this study werereceiving instruction in a self-contained classroom for students with academic and behavioral difficulties.Table 1 Subject cores*BehavioralHistoryScottM612LD87Difficulty getting along with others; verbal andphysical altercationsRichardM713LD87Aggression, confrontational behavior; inappropriate talking; not following directionsDaveM813OHI-ADHDN/ATalking out; defiance; inattention to tasks;manipulation of othersRachelF712LI/OHI-ADHDN/AInterpersonal problems; conduct disorder;oppositional behaviors; and depression*Scott and Richard, Stanford-Binet IV; Rachel and Dave did not have this information in their files. Primary labels are as follows: learning disabled (LD), other health impairment-attention deficit hyperactivitydisorder (OHI-ADHD), and language impairment (LI).

56 / Reading ImprovementMeasuresDescriptive AssessmentsAll participants in the study were administered a series o f standardized assessmentinstruments to ensure they would benefit frominclusion in the study. All the participants inthe study had to score at or below the 30thpercentile on the Broad Reading subscaleo f the Woodcock Johnson Tests o f Achievement-Third Edition (Woodcock, McGrew, &Mather, 2001) and at or below the 30th percentile on the Gray Oral Reading Tests-FourthEdition (Wiederholt & Bryant, 2001) to beincluded in the study. Participants also hadto perform at or below the 50th percentile onthe Behavior Rating Profile-Second Edition(Brown & Hammill, 1990). Standard scoresand percentile ranks are reported for each o fthese assessments and are found in Table 2.Dependent VariablesTwo dependent variables were administered at the end o f both baseline and intervention sessionsA.Near-transfer measure (SRA). The firstdependent variable was a timed measure o f anequivalent ability level passage that the student read aloud to determine the effect o f theintervention on the oral reading rate and accuracy o f the participant. The passages weretaken from the SRA Multiple Skills Series:Reading Curriculum (Boning, 1998). Basedon their reading ability levels, three o f theparticipants read passages on the curriculum’sthird grade level, while one read passageson the second grade level. Students wereinstructed to read the passage as quickly asthey could following standardized directions.A trained RA timed the participant readingthe complete passage and marked any errorsin his/her reading. A words correct per minute(WCPM) score was calculated by dividingthe total number o f words read correctly bythe total time in minutes taken to read thepassage.SRA comprehension measure. The seconddependent variable was a set o f five multiple-choice comprehension questions relatedto the passage that the student had read. Thecomprehension questions were taken from theSRA Multiple Skills Series: Reading Curriculum (Boning, 1998). The comprehensionquestions were standardized and followed thesame format throughout the passages. Afterthe student read the passage, the passage wasremoved and the five comprehension questions were placed in front o f the student. Thestudent followed along while the examinerread each question and the four possible answers aloud to the student. The student wouldthen choose the answer that he/she thoughtwas correct.BRP-27 4 (4 )84(15)7 3 (4 )83(13)75 (5)7 8 (7 )6 7 (1 )10(50)Dave6 8 (2 )7 0 (2 )7 0 (2 )7 2 (3 )6 5 (1 )6 8 (2 )5 8 ( 1 )9 (3 7 )*Numbers in parentheses are percentile rankswj-ni6 (9 )RachelW J-IIIBroadReading7 (1 6 )58 ( 1)WordAttack7 6 (5 )7 2 (3 )wj-m91(28)7 2 (3 )wj-m8 6 (1 7 )7 2 (3 )PassageComp91(27)7 3 (4 )wj-m79 (8)8 0 (9 )Rdg Fluency88(21)7 2 (3 )LetterW ord ID92(30)Richardwj-mScottStudentNam eGORT-4O ral RdgQ uotientBasic RdgSkillsTable 2 Standard Scores and Percentile Ranks on Descriptive Measures

Reading Fluency Interventions for Middle School Students / 57DesignA multiple baseline design across students(Kazdin, 1982) with the addition of a reinforcement/ feedback condition [Read-Model-Read with Contingent Reinforcement andPerformance Feedback (RMR CR/PF)] wasused to determine the effect of a reading fluency intervention [Read-Model-Read (RMR)]on oral reading performance. Implementationof the RMR condition and the RMR CR/PFcondition was staggered across participants.ProceduresThe reading intervention was individuallyimplemented by RAs who received approximately 10 hours of training in implementationof the intervention and the administration ofthe dependent measures. The RAs were taughthow to assess the participants using the dependent measures prior to the baseline phaseof intervention and practiced administeringthe dependent measures on the first author andone another at least five times prior to collecting baseline data. The RAs were specificallytrained on the baseline condition, Read-ModelRead (RMR), and the intervention condition,Read-Model-Read with Contingent Reinforcement and Performance Feedback (RMR CR/PF), prior to implementing each phase with theparticipants. The RA training was led by thefirst author to ensure that treatment fidelity andassessment reliability was consistent prior toimplementing the research study.Each intervention session lasted approximately 20 minutes for each student. Thespecific time for instruction was determinedaccording to each student’s schedule and wasarranged with the classroom teacher. Eachsession was conducted 4 days a week over a12-week period, resulting in approximately 24hours of direct, intensive instruction in reading fluency for each student over the semester.Across all phases of the study, the participantsalso received the regularly scheduled readinginstruction in their classroom.Intervention PhasesBaseline. During the baseline condition,in order to control for individualized attentionduring intervention phases, a RA removedthe participant from the classroom and readto the participant from the newspaper, book,or magazine of his/her choosing for 10 minutes. While participants were allowed to askquestions regarding the reading, no instruction was provided. Read-Model-Read (RMR).During the RMR condition, the student metwith the RA for approximately 20 minutes.The student first read the training passageof text taken from the QuickReads program(Hiebert, 2003) silently to himself/herself.Next, the student followed along with his/her finger while the RA modeled a slow-ratefluent reading of the passage (100-120 wpm).Then, the student read the passage out loud.After reading the passage three times, the student was timed on the final reading of the passage. After completing dependent measures,the student was praised for working hard andreturned to the classroom.Read-Model-Read Contingent Reinforcement/Performance Feedback (RMR CR/PF).During the RMR CR/PF phase of the intervention, the participants continued to receivethe RMR instruction with the addition of theCR/PF component. Prior to implementing thiscomponent, participants completed a preference assessment to determine items that werereinforcing for them. The choices were takenfrom the participants’ interests and from alist of items that were allowed in the schoolsetting. Participants were asked to rank ordertheir choices for preferred items with 1 beingthe most desirable and 10 being the least desirable. Participants were allowed to decideon the reinforcer of the day prior to readingthe training passage.At the beginning of this phase, a readinggoal of WCPM was determined for eachstudent based on his/her prior reading performance on the training passages. When

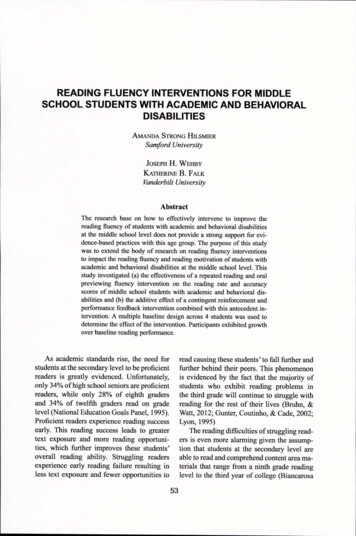

58 / Reading Improvementexamining student performance on the training passages in the previous phase, an initialgoal was set between 115 and 120 WCPM foreach student. If a student surpassed this goal3 days in a row, a new goal was determinedbased on his/her current reading level. Participants were told that if their reading goalswere met, then they would receive a preferreditem. After completing the RMR instructionand transfer passage, the participants graphedtheir performance. Next, participants visuallyanalyzed their performance on the graph anddetermined if they met the criterion level toreceive a reward. If a student met their goal,he/she was allowed to select a preferred itemfrom the previously generated list.For each participant, two follow-up probeswere administered 2 weeks after the completion of the final intervention component todetermine the long-term effects of the readingintervention on the reading fluency of eachparticipant.Treatment IntegrityTreatment integrity checks were conducted weekly across all phases to ensure that theimplementation of the intervention and theprocedures for administering the assessmentswere followed appropriately. The first authorserved as the observer for the treatment integrity checks and had a copy of the script for theintervention and assessment administration.Treatment integrity for the administration ofthe intervention ranged from 90-100% accuracy with a mean score o f 99.8% accuracy.The treatment integrity for the assessment administration ranged from 90-100% accuracywith a mean of 99.8% accuracy.Interobserver AgreementLive agreement checks on the readingprobes were conducted weekly by the firstauthor to ensure that the scoring of the assessment instruments was accurate and reliable.The first author sat close to the student to hearthe reading, but could not see the other examiner’s passage as she scored. The first author had a copy of the assessment and scoredalongside the examiner to determine theaccuracy of scoring errors and timing of responses. Reliability was conducted on 29% ofthe SRA passages and comprehension probes.The reliability percentage ranged from 98.1%to 99.3% with a mean of 98.4% for the SRAprobe, and 100% agreement on comprehension probes.ResultsData were analyzed using visual inspection and the calculation of means and standarddeviations. The dependent variables that wereused to determine the effect of the intervention included (1) a near-transfer reading ability probe, and (2) a reading comprehensionmeasure.Near-Transfer Probe (SRA)The results of the near-transfer probeswere analyzed using visual analysis (Figure1) and calculation of means and standard deviations by phases.ScottScott was the first participant to receivethe read-model-read (RMR) intervention.Visual inspection of showed a decreasingtrend during baseline conditions, which wasfollowed by an accelerating trend followingthe introduction of the RMR intervention. Thecomparison of his baseline score mean (M 75.2, SD 9.94) to his RMR phase mean(M 94.38, SD 11.53) indicates that Scottexhibited mean growth as a result of the firstintervention phase. During the RMR CR/PFphase, following an initial drop in level, Scottmaintained an accelerating trend, although toa slightly lesser degree than was observed inthe prior condition resulting in an average of99.93 WCPM (SD 15.90). However, Scott’sperformance was variable in all phases.

Reading Fluency Interventions for Middle School Students / 59Figure 1 SRA words correct per minuteRichardDuring baseline, Richard’s performancewas relatively flat with no discerning trend(M 77 WCPM; SD 11.19) although hisresponding was variable. Following implementation of the RMR condition, there was aninitial change in level and movement towarda slight accelerating trend (M 81.83 WCPM;SD 8.33) during the RMR phase. Duringthe RMR CR/PF phase, Richard’s oral reading performance increased to 89.86 WCPM(SD 12.19). Although there was an initial dropin level as compared to the previous phase, amore accelerating trend was initially observedand variability in daily performance was noted.DaveO f all participants, Dave exhibited thelowest oral reading performance during baseline with a decreasing trend (M 65.47; SD 8.32). During the RMR phase of intervention,there were slightly higher levels of correct

60 / Reading Improvementresponding although with a slight accelerationin trend (M 73 WCPM; SD 9.27), which revealed some mean growth over Dave’s baseline reading performance. The RMR CR/PFphase appeared to have a greater effect onDave’s oral reading performance upon initialintroduction. After an initial downward trendin RMR CR/PF, a slight rise in trend wasnoted (M 77.88 WCPM; SD 12.65. Davealso showed considerable variability duringthe different phases with noted improvementover his baseline reading performance.RachelRachel’s performance during baseline wasvariable with an accelerating trend and washigher than the other 3 participants (M 95.64WCPM; SD 17.52). Following the introduction of the RMR phase, there appeared to bean initial change in overall level althoughthe overall trend was decelerating, primarilydue to the final two data points of this phase(M 125.82 WCPM; SD 19.66). However,Rachel did not appear to benefit from theRMR CR/PF phase of the intervention. Herreading performance during this phase wasslightly lower than in the RMR phase (M 119.33 WCPM; D 16.85), although trendacceleration and greater reading consistencywas observed.Follow-Up PhaseTwo follow up probes were administeredto each participant two weeks following thecompletion of their final intervention phasesto determine the long-term effect of the intervention on reading fluency. Upon visual inspection, Scott, Richard, and Dave exhibitedmean reading growth in the follow-up phaseprobes on the near-transfer measures. Rachelexhibited a decline on the near transfer. Overall, the participants showed growth on thefollow up probes with considerable variabilityconsistent with their performance dining thetwo intervention phases.SRA ComprehensionThe mean results for the comprehensionquestions are presented in Table 3. Examination of baseline performance of participantsindicates participants were answering anaverage of 3 to 4.89 comprehension questions correctly without intervention. Whenthe RMR phase was implemented, all of theparticipants experienced growth over theirbaseline comprehension performances withDave showing the most consistent growthfrom baseline to RMR.Only 2 participants exhibited growth withthe introduction o f the RMR CR/PF intervention. Scott and Rachel both showed minimalgrowth from RMR to RMR CR/PF. Richardand Dave both experienced decreases in themean comprehension questions answeredcorrectly during the RMR CR/PF phase.Overall, the majority of the participants answered an average of 3.97 comprehensionquestions correctly during baseline and anaverage of 4.32 comprehension questionscorrectly during the RMR and RMR CR/PFphases.DiscussionPoor achievement in reading is a hallmarkcharacteristic of participants with academicand behavioral disabilities. Although therehave been a number of studies that have investigated the effectiveness of fluency training,only six studies were found that specificallyaddressed middle school participants withacademic and behavioral disabilities (Lewis-Lancaster & Reisener, 2013; Mansett-Williamson & Nelson, 2005; Mercer et al., 2000;Morris & Gaffney, 2011; Strong et al., 2004;Wanzek et al., 2011). The reading difficultiesassociated with participants with academicand behavioral disabilities impact the abilityto decode words effectively and read fluently.Reading fluently is perhaps most importantfor older participants who are required to read

Reading Fluency Interventions for Middle School Students / 61and comprehend sophisticated text. Unfortunately, the research on effective methods forimproving the reading fluency of secondarystudents with academic and behavioral disabilities indicates variability and inconsistentgrowth in students in this age group.The current study extends the research inthis area due to the inclusion of nonrelatedtext as a dependent variable. In addition, thestudy was designed to meet, at least in part,the standards of quality by which the studycould be evaluated for its potential contribution to the needed research in reading fluencyfor middle school age participants with academic and behavioral disabilities.The results of this study found growthin oral reading fluency over the baselineperformance of the participants during theintervention phases. A near-transfer measureof nonrelated text was used to measure theeffectiveness of the fluency intervention onstudent oral reading performance. Resultsfrom this study revealed improved fluencyfrom the baseline phase to the RMR phaseof intervention for all participants. Once theRMR CR/PF phase was introduced, 3 of the4 participants demonstrated mean growth inwords read correctly per minute. Participantreading accuracy on this measure ranged from91% to 96% across all phases of intervention.While the RMR phase and the RMR CR/PF phases appeared effective in improvingstudent oral reading performance, the clinicalsignificance of these results is unclear. Despite the improvements, the oral reading ratesof the participants remained far below agenorms established for 7th and 8th grade participants who are average readers. O f particularconcern was the day-to-day variability inreading performance. This finding is consistent with previous findings on the reading performance of participants with academic andbehavioral disabilities (Falk & Wehby, 2001;Strong et al., 2004; Wehby, Falk, Barton-Arwood, Lane, & Cooley, 2003). However, thesource of this variability is unknown.Participant performance on the comprehension questions was consistent across allphases for 3 of the 4 participants. Scott, Richard, and Rachel all showed improvement overbaseline levels of performance during theRMR and RMR CR/PF phase. Dave was theonly participant whose reading comprehension performance fell below baseline levelsduring the RMR CR/PF phase. There wasno significant difference in comprehensionscores for participants with the addition ofthe RMR CR/PF condition. These findingsmay have been the result of a ceiling effectdue to the limited number of comprehensionquestions. A comprehension measure thatconsisted of more questions may have yieldeddifferent results.There were several interesting patternsexhibited by the participants over the courseof the study. During the RMR phase, allparticipants exhibited mean growth overbaseline performance. However, participantsappeared to have some difficulty adjusting tothe RMR CR/PF condition. A similar patternTable 3 Average Mean Performance Across SRA Comprehension SessionsStudentB LM eanBLSDMeanRM R SDMeanC R achel3.751.1754.0910.7014.2220.667

62 / Reading Improvementwas reported by Arthaud and Rankin (1996)in their research on the use of differentialfeedback to improve student oral readingperformance. This initial decrease during theRMR CR/PF condition may be explainedby student anxiety about receiving feedbackon reading performance or an inability tohandle feedback on academic performance.Additional measures examining the effectof anxiety on attitudes or experience towardfeedback may have provided greater insightinto this phenomenon.Limitations of StudyAlthough the results of this study arepromising, several limitations should beconsidered when evaluating these results.First, although the classroom had a standardreading program, due to behavioral issues orother unplanned activities, implementationof this curriculum was not accomplished ona consistent basis. The inconsistency of thisreading instruction could have had an effecton the oral reading performance of the participants in the study.Secondly, the inability to control the dayto-day variability in reading performanceof these participants was problematic. Onemethod of understanding this variabilitywould be to collect daily data from the teacheron the behavioral performance of participantsand use this information to evaluate studentperformance in reading. Also, observationof student behavioral performance would beuseful in determining factors that affect student academic performance.Finally, a third limitation in this study concerns the reinforcement and feedback provided for the training passages. The transfer effect of the reinforcement and feedback to thedependent measures was difficult to discern.The effect of the RMR CR/PF condition mayhave been greater if the reinforcement andfeedback occurred on the dependent measurepassages rather than the training passages.Future Research DirectionsBased on the literature review and theprocedures incorporated in this study, several areas of future research can be identified.First, additional studies should incorporatemeasures of ongoing classroom curriculuminstructions standard measures which includeboth the frequency of implementation as wellas the integrity of ‘practice as usual’ in orderto aid in the understanding o f supplementalfluency programs liked the ones used in thisstudy. In regard to implications for practice,this would mean that teachers and administrators need to reconsider the importance ofreading instruction at the middle school leveland institutions of higher education shouldcreate more structured training on ways toprepare secondary teachers to teach reading intheir content area (Joseph & Schisler, 2009).With regard to dependent measures, a second area of future research is to further investigate the usefulness of the repeated readingand oral previewing intervention on equivalent transfer text. This research should examine the transfer effect of a fluency intervention on equivalent text and what the absenceof such transfer says about the usefulness ofthe intervention. Collecting multiple readingprobes on both equivalent transfer text aswell as far transfer measures of classroomcurricula will assist in understanding the degree to

to impact the reading fluency and reading motivation of students with academic and behavioral disabilities at the middle school level. This study investigated (a) the effectiveness of a repeated reading and oral previewing fluency intervention on the reading rate and accuracy scores o