Transcription

Predicting Satisfaction and Commitment in Adult Romantic Involvements: An Assessment ofthe Generalizability of the Investment ModelAuthor(s): Caryl E. Rusbult, Dennis J. Johnson, Gregory D. MorrowSource: Social Psychology Quarterly, Vol. 49, No. 1 (Mar., 1986), pp. 81-89Published by: American Sociological AssociationStable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2786859Accessed: 22/01/2010 14:26Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available rms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unlessyou have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and youmay use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use.Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained herCode asa.Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printedpage of such transmission.JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range ofcontent in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new formsof scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.American Sociological Association is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access toSocial Psychology Quarterly.http://www.jstor.org

INVESTMENT MODELbal response mode use." Journal of AbnormalChild Psychology 9:229-41.81nitive versus rhetoricalstyle hypothesis."Journalof Personality and Social Psychology 46:979-90.Tetlock, PhilipE. 1981."Pre-to post-electionshifts United States House of Representatives.1974.Inauin presidentialrhetoric: Impression managementgural Addresses of the Presidents of the Unitedor cognitive adjustment." Journal of Personalityand Social Psychology 42:207-12. 1983. "Psychological research on foreignpolicy: A methodologicaloverview." Pp. 45-78 inReview of Personality and Social Psychology,editedby LaddWheeler.BeverlyHills, CA: Sage.Tetlock, Philip E., KristenA. Hannumand PatrickM. Micheletti. 1984. "Stabilityand change in thecomplexity of senatorialdebate: Testing the cog-States from George Washington 1789 to RichardMilhous Nixon 1973. House Document 93-208,93rd Congress, 1st Session. Washington, DC:United States GovernmentPrintingOffice.Winter, David and Abigail J. Stewart. 1977. "Content analysis as a techniquefor assessing politicalleaders." Pp. 27-61 in The Psychological Examination of Political Leaders, edited by MargaretHerman.New York: Free Press.Social Psychology Quarterly1986, Vol. 49, No. 1, 81-89Predicting Satisfaction and Commitment in Adult RomanticInvolvements: An Assessment of theGeneralizability of the Investment ModelCARYL E. RUSBULTDENNIS J. JOHNSONGREGORYD. MORROWUniversity of KentuckyA cross-sectional survey of adult romantic involvements was conducted to assess thegeneralizability of investment model predictions (Rusbult, 1980a; 1983). According to theinvestment model, satisfaction with a relationship should be greater to the extent that arelationship provides high rewards and low costs, whereas commitment increases not only dueto greater relationship satisfaction, but also to increases in the investment of resources inrelationships and declines in the quality of available alternative partners. Consistent with modelpredictions, satisfaction was positively related to level of rewards, and commitment waspositively associated with satisfaction, negatively associated with alternative quality, andpositively associated with investment size. Greater reward value, too, promoted greatercommitment to maintain relationships. However, costs did not powerfully or consistently affectsatisfaction or commitment to relationships. The generalizability of the model for selecteddemographic subsamples-females and males, married and single persons, younger and olderpersons, persons with greater and lesser education and income, andfor relationships of greaterand lesser duration-is also evaluated. The obtained findings provide good support for thegeneralizability of the investment model.Social scientists who study close relationships have become increasingly concernedwith identifying the determinants of commitment to maintain relationships (e.g., Becker,1960; Johnson, 1973; 1982; Levinger, 1974;This researchwas supportedby a grantto the firstauthor from the University of Kentucky ResearchFoundation.The authorswish to express their gratitude to Martha Hyatt, Jerry Schroeder and AnnSturgill for their help in conducting this research.Requests for reprintsmay be sent to CarylRusbult,Departmentof Psychology, Universityof Kentucky,Lexington, KY 40506.1979; Rusbult, 1980a; 1983). Of the extantmodels of commitment, Rusbult's investmentmodel has been shownto be particularlyrobustin its ability to predict commitmentin a widerange of settings-in dating relationships(Rusbult, 1980a;1983),in friendships(Rusbult,1980b), and on the job (Farrell and Rusbult,1981; Rusbult and Farrell, 1983). The investmentmodelextends concepts developedwithinthe exchange tradition (c.f., Blau, 1964; Homans, 1961;LaGaipa,1977),particularlythoseof interdependence theory (Kelley andThibaut,1978;Thibautand Kelley, 1959).As ininterdependencetheory, the investmentmodel

82SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY QUARTERLYdistinguishesbetween satisfaction-positivityof affect or attractionto one's relationshipand commitment-thetendency to maintain arelationshipand feel psychologicallyattachedto it. (Using Johnson's [1982]terminology,thepresentdefinitionof commitmentincludesbothpersonal and structuralcommitment.)The investmentmodel asserts that individuals should feel more satisfied with their relationshipsto the extent that they providehighrewards(e.g., a brightor physically attractivepartner,attitudinalsimilaritywith partner),involve low costs (e.g., infrequentarguments,physicalproximity),and exceed theircomparison level, or expectationsregardingthe qualityof close relationships. Commitmentto maintain relationshipsshould be affected by threefactors. First, to the degree that a relationshipis satisfying, commitmentshould be stronger.Second, persons should feel more committedto the extent that they have only poor alternatives to their current involvements (i.e., aless-satisfyingrelationshipwith someone else,spending time alone and not liking it). Third,commitment should be greater to the degreethat the individualhas invested numerousresources in the relationshipeither intrinsically(e.g., time, effort, self-disclosure)or extrinsically (e.g., mutualfriends, sharedmemoriesormaterialpossessions).IPrior research provides very good supportfor model predictions. Rusbult (1980a) conducted two studies, a role-playingexperimentand a cross-sectionalsurvey, as initialtests ofthe model, and Rusbult (1983) carried out aseven-month longitudinal study to exploremore dynamic,process-orientedaspects of themodel. In all three studies, the findings weregenerally consistent with predictions. Greaterrewards and (generally) lower costs inducedhigher satisfaction, and strongercommitmentresulted from greater satisfaction, poorer alternatives and greater investment size. Surprisingly, while rewards were positively predictive of commitment,costs were unrelatedto, or only weakly related to level of reportedcommitment. Also, as was noted above, theinvestment model has been shown to predictcommitmentto friendshipsas well as job com-mitmentand turnover.Such generalizabilityisimpressivein light of argumentsthat differenttypes of relationships-marriedversus unmarried, exchangeversus communal,shorter-termversus longer-term-may be maintained byvery differentprocesses (Clarkand Mills, 1979;Duck, 1984). Unfortunately, the generalizabilityof the investmentmodel may be limited in one respect: Prior studies of romanticinvolvementshave been limited to college-agedating relationships. We do not yet knowwhether the investment model can effectivelypredict satisfaction and commitmentin morelongstandingrelationships.The present study, a cross-sectional community survey of ongoing, adult romantic involvements, is designedto replicateandextendprevious investmentmodel researchin severalrespects. First, since the generalizabilityofprevious research was limited by its focus oncollege-age dating relationships, the presentstudy examines a more heterogeneouspopulation of adults involved in more longstandingromantic involvements. Second, the presentstudy explores the predictive power of themodel for selected subsamples of the overallpopulation(e.g., marriedversus singlepersons,males versus females). In light of the priorpredictivepowerof the model, it was expectedthatinvestment model predictions would holdequally well across all demographicallydefined subsamples. Third, the present studyexamines the direct relationship between investment model variables and a variety ofdemographiccharacteristics-gender, age, income, education,maritalstatusand durationofrelationship.Our examinationof the impactofthese particulardemographiccharacteristicsisfrankly exploratory (i.e., we extended no apriori hypotheses regarding their impact).These factors were investigatedbecause theyare most commonly examined in sociologicalresearch and because they have previouslybeen shown to be associated with other important behaviors in close relationships(e.g.,Albrechtet al., 1979;Ewer et al., 1979;Fengler, 1973;Lurie, 1974; Schoen, 1975).METHODRespondents and ProcedurePredictionsconcerningthe effects of satisfactionand alternativequality on commitmentto relationships were originally derived from interpersonalinterdependencetheory (Thibautand Kelley, 1959;Kelley and Thibaut, 1978), and are congruentwithLevinger's (1979) social exchange view on the dissolution of pair relationships.The predictionconcerningthe impact of investment size is originaltothe investmentmodel, althoughit is congruentwithother exchange theories (c.f., Blau, 1964;Homans,1961).ISix hundred individuals were randomlyselected from the Lexington, Kentucky telephone directory. Each was mailed a packetcontaining a cover letter, an "InterpersonalBehaviorQuestionnaire"and a stampedreturnenvelope. One-half of the packets requestedthat the adultfemale of the house complete thequestionnaire;if no adult female lived at thatresidence then the adult male was asked to doso. The otherhalfof the packetsreversedthese

INVESTMENT MODELinstructions.If individualsfailed to respondtothe first mailing, a second packet was sent,followed finally by a third set of materials.2Five hundred packets were sent via bulkmail, which constitutedthe most cost-effectivemethod of distribution. Items that are bulkmailed, however, are not forwarded or returned to the sender if they reach an invalidaddress. Therefore, to obtain an accurate return rate estimate, 100 packets were mailedfirst class. Of these 100, 11 were returnedbecause of invalid addresses and 38 were completed and returnedto the investigator.Thus,the estimated overall response rate was 43percent-38 out of 89.3 An additional171 persons responded to the bulk mailing. The totalresponse, then, was 209 persons, 130of whomwere currently involved in serious relationships (79 persons were not currentlyinvolved).These 130persons were the respondentsin thestudy. 58 percentwere female, 95 percentwerecaucasianand 74 percent were married.Theirmean age was around33, they had an averageof 3 years of college educationand their meanpersonal income was approximately 14,000.42 Dillman's (1978) "total design" techniques ofquestionnaireconstruction and follow-up mailingswere utilized in an attempt to maximize responseaccuracy and rate.I Our response rate estimate must be based onlyupon this 100packet samplebecause it is impossibleto determinehow many of the bulk-mailedpacketswere "terminated"due to changed or invalid addresses. Thoughwe knowfromourfirstclass mailingthat approximately11 percent of our packets wereterminateddue to invalidaddresses,we have no wayof determiningwhat percentagewere terminateddueto changedaddresses. Thus, we cannot directly extrapolateresponse rates from the first class mailingto estimate the response rate for the bulk-mailing.4 The representativenessof this sample is not aserious concern because we are testing theoreticalrelationshipsamong variablesratherthan assessingthe incidence of a phenomenonin the generalpopulation (Kidder, 1981).Nevertheless, these figuresdocompare favorably to those obtained for the samegeographicregion in a recent 51 percent responserate mailed questionnairereportedby Rusbult andZembrodt(1982) (53%female, 95%caucasian, 63%married,mean age of 37, and mean educationof 2.5years of college) and to those obtainedin a recent63percent response rate telephone survey conductedby the University of Kentucky Survey ResearchCenter(54%female, medianage between 25 and 40,median education between one and three years ofcollege). Percent marriedwas higher in the presentsurveybecausesurveythanin the Rusbult-Zembrodtthe present survey includedonly persons who werecurrentlyinvolved in serious relationships,whereasthe former survey included all persons who had atsome time been involved in serious relationships.Data regardingincome levels were not comparable,since the present survey assessed personal income83QuestionnaireThe questionnaireincluded measures of allmodel variables-reward value, cost value, investment size, alternativequality, satisfactionand commitment.5Respondentsalso providedinformation regarding demographic characteristics. Unless otherwise indicated, itemswere 5-point Likert scales. First, demographicinformationregardinggender, age (10categories), race, education (7 categories) andpersonal income (10 categories)was obtained.Respondentsalso indicatedwhetherthey weremarried, dating regularly or not involved.Those who were not currentlyinvolved wereasked to complete this generalinformationandreturn the questionnaire. Respondents whowere married or dating someone regularlycompleted the remainderof the questionnaire.In order to obtain comparablemeasures of allmodel variables, we asked that respondentsadopt a similar time perspective-to describetheir relationshipsas they stood just prior totheir most recent period of dissatisfaction.6Inaddition, we felt that respondents would notreadily understandand be capable of answering questions concerning rewards, costs, investments and alternatives, so both specificand generalitems were provided,followingtheprocedure utilized in Rusbult (1980a). In essense, the specific items "taught"respondentsthe meaning of the constructs tapped in thegeneral items.The specific items assessing rewards andcosts concerned, for example, the partner'spersonality, sense of humor and intelligence,and the partners'sex life, way of handlingconflicts and division of household tasks or childcare. Two general items assessed relationshipand the comparisonsurveys assessed householdincome. Thus, the sample obtained in the presentstudy appearsto be demographicallysimilarto thatobtained in comparable research using the samepopulation.S We will not examine the effects of variationsincomparisonlevel on satisfactionor commitmentbecause it is extremelydifficultfor personsto separatethat which exists objectively (reward value, costvalue) from that which they expect more generally(comparisonlevel).6 This time perspectivewas employedbecause:(a)it allowed us to assess respondents'feelings abouttheir relationships during similar relationship"states" (i.e., duringa nontroubledperiod);and (b)this survey was designed to provide data for twoprojects, and such a time perspective was essentialfor the second project. A full 60 percent of the respondents described problems that had occurredwithinthe last month,so we can feel relativelyconfident that findingsreportedbelow do not result fromthe "warm glow" of retrospective reports of thestatus of relationshipsin the distant past.

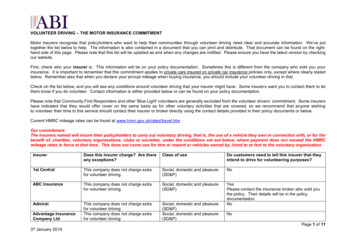

84SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY QUARTERLYrewards: "The good traits your partner possesses and the good thingsaboutyour relationship are termed'rewards.'How rewarding[is]your relationship?"and "In general, how [do]the rewardsyou [get] out of your relationshipcompare to those of other people's relationships?" Two general items assessed costs:"The bad traitsyour partnerpossesses and thebad things about your relationshipare termed'costs.' How costly [is] yourrelationship?"and"In general,how [do] the costs you [get]out ofyour relationshipcompare to those of otherpeople's?"The specific items assessing investmentsizeconcerned, for example, shared friends andmaterial possessions, financial security, selfdisclosures, effort expenditureand numberofchildren.The generalmeasureswere: "Generally speaking,how much [have]you invested inyour relationship (e.g., time, energy, selfdisclosures, sharedexperiences, emotionalinvestments)?"and "All things considered,howmuch [have]you 'put into' your relationship?"The specific items assessing alternativequality concerned, for example, the importance of romantic involvement, estimatedtime to begin datingagain if relationshipwereto end, confidenceof findinganotherappealingpartner, enjoyment of time spent alone andlikelihood of finding an appealing alternativepartnerin regardto a variety of specific traits(e.g., personality,physical attractiveness,sexlife). The generalmeasuresof alternativequality were: "Generallyspeaking, how appealing[are]your alternatives(a differentrelationshipor spendingtime without a romanticrelationship)?", "Generally speaking, how [do] youralternatives compare to your relationship?",and "All things considered, how satisfyingwould it [be] to adoptyour alternativesinsteadof your relationship?"Only general measures of satisfaction andcommitment were obtained. The satisfactionmeasures were: "In general, to what extent[are]you attractedto your partner?";"In general, how [does] your relationshipcompare toother people's?"; and "All things considered,how satisfied [are] you with your relationship?". The general commitment measureswere: "For how much longer [do] you wantyour relationshipto last?"; "How committed[are] you to maintainingyour relationship?";"How likely [is] it that your relationship[will]end in the near future?";and "To what extent[do] you feel 'attached'to your partner?"Reliability and Validity of MeasuresReliabilitycoefficients calculatedfor the setof global items designed to measure eachmodel construct revealed sizeable alphas forthe measures of rewards (.85), costs (.63), alternatives (.81), investments (.77), satisfaction(.78) and commitment (.82). Therefore, thegeneral measures of each variable were averaged to form a single estimate of each factor.These averaged measures were employed inthe analyses. To assess the validity of our general measures, we computed the correlationsbetween each general measure and the specificitems associated with that measure. Theseanalyses revealed generally good convergence.The general rewards measure was significantlycorrelated with all specific reward/cost items(median r .29), the costs measure was correlated with 8 of 11 specific reward/cost items(median r -.23), the alternatives generalmeasure was correlated with 13 of 14 specificalternatives items (median r .22), and theinvestments general measure was correlatedwith 8 of 12 specific investments items (medianr .17).RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONPredicting SatisfactionThe investment model asserts that higherreward value and lower cost value should induce greater satisfaction with relationships. Toevaluate these relationships, zero-order correlations and multiple correlations betweensatisfaction and reward and cost value werecalculated for the sample as a whole and forselected demographic subsamples (for age,education, income and duration, a median splitwas used to divide the overall sample into subgroups). A summary of the results of theseanalyses is presented in Table 1.7 The combined impact of reward value and cost value onsatisfaction was significant for the sample as awhole and for all subsamples (refer to Mult. R,df, and F).8 Greater reward value consistentlyencouraged greater satisfaction (refer to REWr). Greater cost value was associated with reduced satisfaction among males, single persons, younger persons, persons with greater7To determinewhetherthe retrospectivenatureofrespondents'descriptionsof theirrelationshipscouldhave affected our findings, we divided our sampleinto two groups-those who describedtheirrelationships as they stood withinone monthand those whodescribedtheir relationships(and problemsin theirrelationships) in the more distant past. We performedzero-ordercorrelationsamongall investmentmodel variables separately for these two subsamples, and found virtuallyidenticalpatternsof resultsfor the two groups.8 The degrees of freedomfor the various analysesdifferslightlyacross analysesdue to missingdataonsome variables.

INVESTMENT MODEL85Table 1. Correlations Between Satisfaction and Reward and Cost ValueaOverall SampleGenderFemalesMalesMarital StatusMarriedSingleAgeUnder 3535 or OlderEducationLess Than Bachelor'sBachelor's or MoreIncomeLess Than 15,000 15,000 or MoreDuration of RelationshipLess Than 10 Years10 Years or MoreaREW reward value and CST*p .05.*p .01. Mult. .622,672,4913.09**15.44**.50**.93**- 762,602,4540.86**30.87**REW rSatisfaction with:CST rcost value.education or income and for persons inlonger-term involvements (refer to CST r).These findingsare consistent with investmentmodel predictions.Costs were not significantlyrelated to reportedsatisfactionfor the overallsample,however,or for the remainingsix demographic subsamples (females, married persons, older persons, persons with lesser education, persons with lower incomes and persons in shorter-termrelationships).These nonsignificanteffects will be discussed below.Predicting CommitmentImpact of satisfaction, alternatives and in-vestments. The model asserts thatcommitmentshouldbe greatto the degreethat satisfactionishigh, alternativesare poor and investmentsizeis great. A summaryof zero-orderand multiplecorrelationsassessing these predictionsfor theoverall sampleand for subsamplesis presentedin Table 2. The combinedimpactof these variables on commitmentwas statistically signifi-Table 2. Correlations Between Commitment and Satisfaction, Alternative Quality and Investment SizeaCommitment with:SAT rALT rMult. RdfFOverall SampleGenderFemaleMaleMarital StatusMarriedSingleAgeUnder 3535 or OlderEducationLess Than Bachelor'sBachelor's or MoreIncomeLess Than 15,000 15,000 or MoreDuration of RelationshipLess Than 10 Years10 Years or .50**-.06.77.563,593,4428.18**6.59**aSAT satisfaction, ALT *p .05.**p .01.INV ralternative quality and INV investment sizc

SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY QUARTERLY86cant for the overall sample and for all subsamples. Higher levels of commitmentwere consistently inducedby highersatisfactionand bypoorer alternatives. Greater investment sizeconsistently encouragedstrongercommitment(10 of 13 r's were significant), but theinvestment-commitmentrelationship was notsignificantfor single persons, youngerpersonsand persons in longer-termrelationships.(Weare not seriouslytroubledby these few nonsignificant effects of investment size, since theyare generally in the predicted direction).Impact of rewards, costs, alternatives andinvestments. Higher rewards, lower costs,poorer alternatives and greater investmentsshould also promote strongercommitment.Asummaryof correlationaltests of these predictions is presented in Table 3. The combinedeffect of these four predictorswas significantfor all groups. Of course, the correlationsbetween commitmentand alternativequalityandinvestment size remain as described eatercommitment,but this effect was not significant for males and persons with greatereducation. For the overall sample and for several subsamples, costs were not significantlyrelated to reportedcommitment.Examinationof Table 3 pairs of correlations reveals thatcosts exerted a negative impact on commitment for some subgroupswhile exertinga positive impactfor theircounterparts;highercostsencouraged lower commitment for youngerpersons, persons with greatereducation, persons with higher incomes and persons inlonger-term involvements, whereas highercosts encouraged greater commitment forolder persons, persons with less educationandpersons with lower income.The Impact of CostsThe nonsignificant and/or inconsistent effects of costs on satisfactionand commitmentbearfurtherexamination.Such findingsare notunique to this investigation:Several empiricalinvestigations have reported nonsignificanteffects of costs or related variables(e.g., conflict) on feelings for partners(e.g., Argyle andFurnham, 1983; White, 1983), and severaltheoristshave also suggestedthat such findingsshould not be surprising (e.g., Braiker andKelley, 1979; Scanzoni, 1979). Also, Rusbult(1980a)found that while variationsin costs affected satisfaction, the effects of costs oncommitmentwere weak. And finally, Rusbult(1983) found that variations in costs affectedneither satisfaction nor commitment. Why?We explore four possible explanations.First, adherence to the romantic ideal-thebelief that one accepts a partnerfor richer orpoorer, in sickness and health (given rewardsand costs)-may prevent individualsfrom becoming less satisfied with and committed totheir relationshipsas the costs of doing so increase. If this were so, we should observe anonsignificantor positive effect of cost valueon satisfaction and commitment among subgroups who are known to believe morestrongly in the romantic ideal-males andTable 3. Correlations Between Commitment and Reward Value, Cost Value, Alternative Quality and Investment SizeaCommitment with:REW rCST rALT rMult. 36**.21*.33**- .29**-.35**- *4.64*Overall SampleGenderFemaleMaleMarital StatusMarriedSingleAgeUnder 3535 or OlderEducationLess Than Bachelor'sBachelor's or MoreIncomeLess Than 15,000 15,000 or MoreDuration of RelationshipLess Than 10 Years10 Years or MoreaREW reward value, CST*p .05.**p .01. cost value, ALT INV ralternative quality and INV investment size.

INVESTMENT MODELyoungerpersons (Hatkoffand Lasswell, 1979;Rubin, 1973).Both of these relationshipswerenegative, however, in the present study.Second, it is possible that the reward-costdifferential predicts satisfaction and commitmentmoreeffectivelythando rewardsandcostsindividually;that is, thatit is not absolutelevelof costs, but level of costs relative to level ofrewards that predicts satisfaction and commitment. However, we calculated a rewardcost differential score for each respondent,performedfurtheranalyses, and found that:(a)rewardvalue alone predictedsatisfactionbetter than did the reward-costdifferentialfor theoverall sample(the respectiveR's were .67 and.24) and for most subsamples (9 of 12), andreward value alone predicted commitmentbetter than did the reward-costdifferentialforthe overall sample (R's were .29 and .17) andfor most subsamples(7 of 12);and (b) the prediction of satisfactionfrom reward value andcost value was superior to that from thereward-costdifferentialfor the overall sample(R's were .55 and .24) and for most subsamples(9 of 12), and the prediction of commitmentfrom reward value and cost value (plus alternatives and investments)was superiorto thatfrom the reward-costdifferential(plus alternatives and investments) for the overall sample(the R's were .62 and .61) and for most subsamples (10 of 12).Third,it is possible that there is a thresholdeffect for cost value; perhaps variations incosts do not affect degree of satisfactionandcommitmentwhen costs are low, but come toexert negative effects at higher levels. We divided our sampleinto low and highcost groups(median split) and calculated correlationsbetween cost value and satisfaction and commitment for both groups. Indeed, we foundthat for the low cost group, variationsin costvalue did not significantlyaffect satisfaction(r -.13) or commitment (r -.03),87tion and commitmentin high cost-low rewardinvolvements (r's -.45 and -.36), these re-lations were not significant in high cost/highreward involvements (r's -.12 and -.27),low cost/low reward involvements (r's -.35and -.13), or low cost/high reward involvements (r's - .01 and - .07).Thus, two of our four potentialexplanationsfor the aberranteffects,of cost value on satisfaction and commitment seem promising:There appearsto be a thresholdeffect for theimpact of costs on satisfaction and commitment, and reward and cost value appear tointeract in affecting satisfaction and commitment, high costs producingreduced satisfaction and commitmentespecially given the preconditionof low rewardvalue. This phenomenon, and particularlyth

Review of Personality and Social Psychology, edited by Ladd Wheeler. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage. Tetlock, Philip E., Kristen A. Hannum and Patrick M. Micheletti. 1984. "Stability and change in the complexity of senatorial debate: Testing the cog- nitive versus rhetorical style hypothesis." Journal