Transcription

Behaviour Research and Therapy 141 (2021) 103846Contents lists available at ScienceDirectBehaviour Research and Therapyjournal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/bratVariable-length Cognitive Processing Therapy for posttraumatic stressdisorder in active duty military: Outcomes and predictorsPatricia A. Resick a, *, Jennifer Schuster Wachen b, c, Katherine A. Dondanville d,Stefanie T. LoSavio a, Stacey Young-McCaughan d, Jeffrey S. Yarvis e, Kristi E. Pruiksma d,Abby Blankenship d, Vanessa Jacoby d, Alan L. Peterson d, f, g, Jim Mintz d, for the STRONG STARConsortiumaDepartment of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC, USANational Center for PTSD, VA Boston Healthcare System, Boston, MA, USAcDepartment of Psychiatry, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, MA, USAdDepartment of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, San Antonio, TX, USAeCarl R. Darnall Army Medical Center, Fort Hood, Texas, USAfResearch and Development Service, South Texas Veterans Health Care System, San Antonio, TX, USAgDepartment of Psychology, University of Texas at San Antonio, San Antonio, TX, USAbA R T I C L E I N F OA B S T R A C TKeywords:Posttraumatic stress disorderPTSDCognitive processing therapyMilitaryTreatment predictorsCognitive Processing Therapy (CPT) is an evidence-based therapy recommended for posttraumatic stress disorder(PTSD). However, rates of improvement and remission are lower in veterans and active duty military comparedto civilians. Although CPT was developed as a 12-session therapy, varying the number of sessions based onpatient response has improved outcomes in a civilian study. This paper describes outcomes of a clinical trial ofvariable-length CPT among an active duty sample. Aims were to determine if service members would benefitfrom varying the dose of treatment and identify predictors of treatment length needed to reach good end-state(PTSD Checklist-5 19). This was a within-subjects trial in which all participants received CPT (N 127).Predictor variables included demographic, symptom, and trauma-related variables; internalizing/externalizingpersonality traits; and readiness for change. Varying treatment length resulted in more patients achieving goodend-state. Best predictors of nonresponse or needing longer treatment were pretreatment depression and PTSDseverity, internalizing temperament, being in precontemplation stage of readiness for change, and AfricanAmerican race. Controlling for differences in demographics and initial PTSD symptom severity, the outcomesusing a variable-length CPT protocol were superior to the outcomes of a prior study using a fixed, 12-session CPTprotocol.ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT023818.There have been more than 20 randomized clinical trials (RCT)demonstrating the efficacy of Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT) forposttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) among people with a wide range oftraumatic experiences, including civilians (e.g., Chard, 2005; Resicket al., 2002), veterans (e.g., Monson et al., 2006; Morland et al., 2014)and active duty military personnel (Resick et al., 2015; Resick, Wachenet al., 2017). However, response to CPT has been less pronounced inveterans and active duty military personnel than in civilians (Dillon etal, 2017, 2019; Steenkamp et al., 2015). In a recent study of CPT withactive duty military personnel, more than half of service membersreceiving the 12-session CPT protocol retained their PTSD diagnosis(Resick, Wachen et al., 2017). These findings suggest that additionalstrategies are needed to improve PTSD treatment outcomes in militarypopulations.* Corresponding author. Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Duke University Medical Center, 1121 West Chapel Hill Street, Suite 201, Durham, NC,27707, USA.E-mail addresses: patricia.resick@duke.edu (P.A. Resick), Jennifer.Wachen@va.gov (J.S. Wachen), Dondanville@uthscsa.edu (K.A. Dondanville), stefanie.losavio@duke.edu (S.T. LoSavio), youngs1@uthscsa.edu (S. Young-McCaughan), jyarvis@tamuct.edu (J.S. Yarvis), Pruiksma@uthscsa.edu (K.E. Pruiksma),BlankenshipA@uthscsa.edu (A. Blankenship), JacobyV@uthscsa.edu (V. Jacoby), petersona3@uthscsa.edu (A.L. Peterson), mintz@uthscsa.edu (J. eceived 12 June 2020; Received in revised form 4 March 2021; Accepted 15 March 2021Available online 25 March 20210005-7967/ 2021 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

P.A. Resick et al.Behaviour Research and Therapy 141 (2021) 103846AbbreviationsGDD, general distress, depressive symptomsIEindependent evaluatorIRBinstitutional review boardMmaintenancePCprecontemplationPCL-5PTSD Checklist for DSM-5MASQMood and Anxiety Symptom QuestionnaireNCOnoncommissioned officerPHQ-9 Patient Health QuestionnairePTSDposttraumatic stress disorderRCIReliable Change IndexURICA-T, University of Rhode Island Change Assessment–TraumaSTRONG STAR South Texas Research Organizational NetworkGuiding Studies on Trauma and ResilienceTriPMTriarchic Psychopathy MeasureAactionAAanxious arousalADanhedonic depressionCcontemplationCAPS-5 Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5CPTCognitive Processing TherapyCRDAMC Carl R. Darnall Army Medical CenterDIS-20 Externalizing Disinhibition SubscaleDSM-5 Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders,Fifth EditionDVBIC Defense and Veterans Brain Injury CenterE-4 to E-6 junior noncommissioned officerE-7 to E-9 senior noncommissioned officerGDA, general distress, mixed symptoms1. Variable-length treatmentdeemed to be “refractory” to treatment after not responding to thestandard 12 sessions.Varying the length of CPT is a topic that has not received muchresearch attention. In a sample of civilians who experienced interper sonal violence, Galovski et al. (2012) tested a variable-length version ofCPT in which participants could receive up to 18 sessions. Treatmentended when participants reached “good end-state,” defined in that studyas less than 21 on the Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale (Foa et al., 1997)and less than 19 on the Beck Depression Inventory-II (Beck et al., 1996;indicating mild levels of symptomatology), negative PTSD status on theClinician-Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS; Blake et al., 1990), andagreement by participant and therapist that treatment goals had beenmet. The criteria required for participants to reach good end-state ismuch more stringent than a simple loss of diagnosis, and even partici pants who demonstrate clinically significant change may not reach thislevel of good end-state functioning. The authors found that more thanhalf of the participants (58%) reached good end-state with fewer than 12sessions, 8% reached good end-state with exactly 12 sessions, and 34%reached good end-state with 13–18 sessions. At the end of the study,nearly all participants (98%) remitted from their PTSD diagnosis. Thesefindings suggest that using a variable-length treatment approach anddefining a treatment completer as someone who reaches a particularend-state of symptoms rather than as someone who has completed afixed number of sessions results in improved therapy outcomes.Only one other study, to our knowledge, has reported effectivenessoutcomes from variable-length CPT. As part of a state-wide learningcollaborative, community providers were trained to implement variablelength CPT (LoSavio et al., 2019). In this sample there were largeeffect-size improvements for both PTSD and depression among treat ment completers. As a follow-up to this study, Dillon et al. (2019)compared civilian (n 136) and military-affiliated (veterans or activeduty; n 63) CPT training cases who attended a variable number oftreatment sessions (M 8.13, SD 4.62, range: 1–17). They found thatboth dropout rates and pretreatment PTSD severity were similar be tween the two groups. However, the civilian patients had slightly betteroutcomes than the military-affiliated patients.Building on the work by Galovski et al. (2012), the purpose of thecurrent study was to test a variable-length version of CPT in active dutymilitary personnel to determine if some would benefit from a longer orshorter dose of treatment. We then aimed to identify which individualsrequire more, fewer, or the standard number of treatment sessions toreach a good end-state of PTSD symptoms. Participants in this studycould receive up to 24 sessions of CPT, which is twice the standard,manualized dose. Thus, a primary goal of this study was to improve theefficacy of CPT in this population through a variable version of CPT byallowing more sessions to patients who otherwise may have been2. Predictors of treatment responseA second aim of this study was to identify pretreatment factors thatpredict therapy response and the length of treatment needed to achieve agood end-state of PTSD symptoms. The study was designed to explore arange of variables that might predict appropriate length of therapy andtreatment outcome. In addition to demographic and military charac teristics, other variables included pretreatment symptom levels, yearssince index trauma, factors related to internalizing or externalizingpersonality traits, and readiness for change. There have been few studiesof predictors of treatment outcome with CPT, and results have beenlargely equivocal.In the Galovski et al. (2012) variable-length study with civilians,time since the trauma and depression severity before starting treatmentwere significant predictors of treatment length. Examining the broaderliterature on demographic predictors of PTSD symptom improvement,findings have been mixed. In one fixed-length CPT study in active dutymilitary (Resick et al., 2020), younger participants exhibited morechange in PTSD symptoms. In a fixed-length CPT study with civilians,younger age was associated with higher treatment dropout (Rizvi et al.,2009). However, Galovski et al. (2012) did not find that age predictedtreatment length in their variable-length CPT study of civilians. Raceand ethnicity have not been shown to predict CPT outcomes in civilianor active duty RCTs with 12-session CPT (Lester et al., 2010; Resicket al., 2020). However, in a large program-evaluation study within theDepartment of Veterans Affairs comparing individual with group CPT A (with written accounts), Lamp et al. (2019) found that Caucasianveterans had greater reductions in PTSD than African American veter ans. They emphasized the importance of culturally competent care. Nomilitary variables were predictive of PTSD symptom change in an activeduty sample receiving either group or individual fixed-length CPT(Resick et al., 2020).Findings also have been mixed on whether pretreatment psycho logical factors are associated with CPT treatment outcomes. Rizvi et al.(2009) found that higher levels of guilt and depression symptom severityat pretreatment were associated with greater improvement in PTSD in asample of civilian women. However, Galovski and colleages (2012)found that higher depression symptom severity at the start of treatmentpredicted a need for more treatment sessions. In an active duty militarysample (Resick et al., 2020), the following pretreatment variables werenot associated with response to CPT over and above age: depression,anxiety, suicidality, guilt cognitions, number of potentially traumaticlife events, state anger, and sleep disruption.2

P.A. Resick et al.Behaviour Research and Therapy 141 (2021) 103846Measures of internalizing and externalizing personality traits havebeen found to be related to different subtypes of PTSD, which might notonly explain the heterogeneity of presentations of PTSD but could alsoaffect treatment outcomes (Miller et al, 2003, 2004, 2008; Miller &Resick, 2007). Low internalizing and externalizing traits are associatedwith PTSD without comorbidity. High internalizing tendencies withPTSD have been associated with low positive temperament, greaterdepression, fear and panic, and avoidant personality, while high exter nalizing coupled with PTSD has been associated with impulsive riskybehavior, substance abuse, and negative temperament. The presence ofthese traits may affect length of time required to reach good end-state,and so they were included as possible predictors of treatment in thisstudy. Most of the studies examining internalzing, externalizing, andPTSD subtypes were conducted with veterans and were descriptive innature. To our knowledge, no studies have examined these varaibleswith active duty military or as a predictor of treatment outcome.Readiness to change when starting PTSD therapy has been examinedin a few studies as a predictor of treatment engagement. Fleming et al.(2018) used a version of the University of Rhode Island ChangeAssessment (URICA-T; Hunt et al., 2006) modified specifically formotivation for trauma treatment to assess retention in therapy amongveterans. They found that readiness for change and a general belief thatone needs help were related to treatment participation (completion of atleast 8 treatment sessions) above and beyond 51 other predictors.Jakupcak et al. (2013) also found that readiness to change was associ ated with a greater number of mental health visits among veterans.However, neither of these studies examined readiness to change as apredictor of symptom outcome. Examining readiness to change as apredictor of outcome is needed.Edition (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association, 2013) during militarydeployment, and met full criteria for PTSD as determined by theClinician-Administered PTSD Scale for the DSM-5 (CAPS-5; Weathers,Blake, et al., 2013). However, the diagnosis of PTSD and treatment focusmay have been based on another, more distressing Criterion A event (e.g., child sexual abuse, domestic violence). The vast majority of partici pants reported that their most distressing Criterion A event occurredduring their military career (83% were combat-related). Only five par ticipants (4%) reported an index event that predated their militaryservice. The remainder occurred during service but were not combatrelated.Exclusion criteria were as minimal as possible to ensure generaliz ability. They included current suicide or homicide risk meriting imme diate crisis intervention, active psychosis, and moderate to severe braininjury (as determined by the inability to comprehend the baselinescreening questionnaires). Other comorbid conditions (e.g., depression,suicidal ideation without immediate intent, substance abuse, personalitydisorders) were not exclusions to participation. Additional exclusionswere known local availability of fewer than 5 months, pending finaldetermination from a Military Medical Evaluation Board to separatefrom service, and ongoing military disciplinary action under the Uni form Code of Military Justice. Participants had to agree to attend twosessions per week to complete as many as 24 sessions within 18 weeks.Military personnel have more geographic instability than other pop ulations. These exclusions were made to increase the likelihood thatparticipants would remain in the area long enough to complete the studyand to exclude participants who might not be motivated for treatment ifthey believed they might be assigned a higher disability rating as part oftheir discharge procedures if they were diagnosed with PTSD. Partici pants were not able to be paid for participation in this study or follow-upassessments per military regulations.3. Present study aimsThe first aim of this study was to characterize active duty servicemembers’ response to a variable-length CPT treatment protocol. Ourhypothesis was that participants would reach good end-state symptomsat varying lengths of CPT treatment, being classified as early good endstate responders ( 12 sessions), standard good end-state responders (12sessions), late good end-state responders (13–24 sessions), or non responders (after either 24 sessions or 18 weeks of treatment) based onthe number of sessions needed to reach a good end-state (defined as ascore of 19 on the PTSD Checklist for DSM-5; PCL-5; Weathers, Litz,et al., 2013). This definition of good end-state is well below the cut-offscore of 33 for probable PTSD on the PCL-5 (Bovin et al., 2016). Oursecond aim was to determine factors that might predict early, standard,or late good end-state response or nonresponse to CPT. These wereexploratory analyses to examine whether individual patient character istics would predict the number of sessions needed to achieve goodend-state; however, because a variable-length protocol had not beenstudied in an active duty military sample, we had no specific hypothesesabout which variables might predict length of treatment or response.Finally, because allowing service members to receive more than 12sessions of treatment, if needed, could improve outcomes, we hypoth esized that given additional sessions, the percentage of participants whosuccessfully remitted from their PTSD would be greater than found in apreviously completed study of the standard 12-session CPT protocolconducted with active duty personnel stationed at the same militaryinstallation (Resick, Wachen, et al., 2017).4.2. Study designThis study was a prospective, within-subjects clinical trial conductedin collaboration with the South Texas Research Organizational NetworkGuiding Studies on Trauma and Resilience (STRONG STAR Consortium).STRONG STAR, based at The University of Texas Health Science Centerat San Antonio (UT Health San Antonio), is a multiinstitutional andmultidisciplinary research consortium of investigators focused on thediagnosis, treatment, and epidemiology of combat-related PTSD andcomorbid conditions. As this was a STRONG STAR-affiliated study,trained research staff employed standardized procedures for therecruitment, screening, assessment (Barnes et al., 2019), and monitoringof research participants. The study was approved by Institutional Re view Boards at UT Health San Antonio, VA Boston Healthcare System,and Duke University Medical School. Carl R. Darnall Army MedicalCenter at Fort Hood, Texas, deferred its review to the UT Health SanAntonio IRB. The study also received approval from the U.S. ArmyMedical Research and Materiel Command (now the U.S. Army MedicalResearch and Development Command) Human Research ProtectionOffice. The methods for this study have been described in detail else where (Wachen et al., 2019).4.2.1. Recruitment and screeningParticipants were recruited through referrals from health care pro viders, or they could self-refer in response to recruitment materialsposted throughout Fort Hood. Research staff spoke with interested in dividuals to describe the study and study procedures. Followinginformed consent, participants completed a baseline assessment. Par ticipants who met all the inclusion and exclusion criteria first met withtheir study therapist for an initial session to confirm the index trauma onwhich to focus in treatment. Participants subsequently met with theirresearch therapist twice a week in 50-min sessions. They continued toreceive CPT sessions until they achieved good end-state symptoms (PCL5 19, described more below), reached the maximum number of4. Materials and methods4.1. ParticipantsParticipants were 127 treatment-seeking, active duty U.S. militarypersonnel, age 18 or older. All participants had deployed to or near Iraqor Afghanistan, had experienced a Criterion A traumatic event asdefined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth3

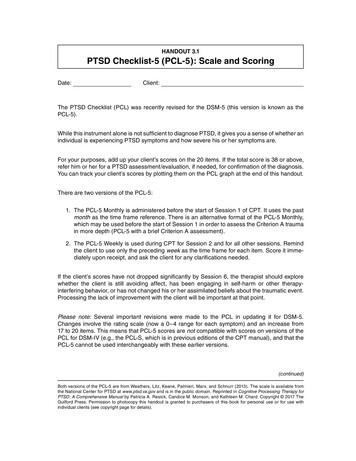

P.A. Resick et al.Behaviour Research and Therapy 141 (2021) 103846sessions (24) allowed by the research protocol, or had been in treatmentfor 18 weeks without reaching good end-state. After the final therapysession, participants returned for a follow-up assessment at 1-monthposttreatment to assess for their PTSD diagnostic status.Externalizing Disinhibition Subscale (DIS-20). The DIS-20 (Pat rick et al., 2013) is a 20-item, modified, brief version of the EXT100(Krueger et al., 2007) designed to measure externalizing traits. Thissubscale captures the domain of general externalizing tendencies andincludes items related to irresponsibility, impulsiveness, dependability,honesty, etc. The DIS-20 is equivalent to the Disinhibition subscale of theTriarchic Psychopathy Measure (TriPM; Strickland et al., 2013). Scoreson this scale correlate 0.95 with scores on the EXT100, which hasexcellent psychometric properties and is related to impulsivity, antiso cial behavior, and substance use.Mood and Anxiety Symptom Questionnaire (MASQ). The MASQShort (Watson & Clark, 1991) is a 62-item scale that assesses tendenciesin the internalizing domain culled from the symptom criteria for theanxiety and mood disorders. Each item is rated on a 1 (not at all) to 5(extremely) Likert-type scale. Factor analytic examinations of the MASQwith student, community, and patient samples have yielded four factors:General Distress, Mixed Symptoms (GDA); General Distress, DepressiveSymptoms (GDD); Anxious Arousal (AA), and Anhedonic Depression(AD), that broadly correspond to the instrument’s conceptually derivedsubscales (Watson et al., 1995a, 1995b).The University of Rhode Island Change Assessment ScaleTrauma (URICA-T). The URICA-T (Hunt et al., 2006) is a 32-item,multidimensional scale assessing attitudes and behaviors about chang ing or addressing trauma issues. The URICA has been used to assessmotivation for psychotherapy, including survivors of sexual abuse withPTSD and veterans with PTSD (Koraleski & Larson, 1997; Murphy et al.,2009; Rosen et al., 2001). Items were modified from the original URICA(McConnaughy et al., 1983) by replacing the word problem with traumaissues. The URICA generates continuous scores on four subscales (Pre contemplation [PC], Contemplation [C], Action [A], and Maintenance[M]) and an overall summary score (C A M - PC).4.2.2. Assessment procedures and measuresDiagnostic clinical interviews were completed by master’s- ordoctoral-prepared independent evaluators (IEs). IEs were initiallytrained with relevant readings, expert didactic instruction, and evalua tion of video-recorded mock and patient interviews. Throughout thestudy, IEs submitted weekly calibration exercises and participated inongoing co-rating exercises to maintain their skills to the STRONG STARConsortium quality standards. The full assessment battery, includingdiagnostic assessments and secondary measures, was administered priorto treatment and 1 month after the final therapy session. Participantsalso completed the PCL-5 (Weathers, Litz, et al., 2013) and PatientHealth Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9; Kroenke et al., 2001) weekly duringtreatment. The PCL-5 scores were used, in part, to determine goodend-state functioning and to consider ending treatment.Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 (CAPS-5). TheCAPS-5 (Weathers, Blake, et al., 2013) is a semi-structured interviewthat assesses PTSD symptom severity and diagnosis. The CAPS-5 deter mined diagnostic criteria for study eligibility as defined by the DSM-5.Symptoms are rated on a scale from 0 (absent) to 4 (extreme/ incapacitating). A total symptom severity score is calculated as the sum ofthe 20 symptom items, with a range of 0–80.PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5). The PCL-5 (Weathers, Litz,et al., 2013) is a 20-item self-report measure of PTSD symptoms asdefined by the DSM-5. Participants rate how much they have beenbothered by the symptoms in the past month (or weekly during treat ment) on a scale from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely), with total scoresranging from 0 to 80. Psychometric characteristics of the PCL-5 havebeen established in veteran (Bovin et al., 2016) and active duty militarysamples (Wortmann et al., 2016). With two samples of veterans, thePCL-5 had a test-retest of 0.85 and good convergent and discriminantvalidity (Bovin et al., 2016). In the Wortmann et al. study, a sample ofover 900 active duty members also demonstrated good convergent anddiscriminative validity and sensitivity to clinical change. They found thecut-off of 33 to be the best predictor of DSM-5 diagnosis. The PCL-5 wasadministered at baseline, the follow-up assessment, and every othersession during treatment. The PCL-5 was the primary outcome measurefor the study, and a score of 19 was used to determine good end-statesymptoms.Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). The PHQ-9 (Kroenke et al.,2001) is the depression module of the PHQ that scores each of the ninecriteria for major depressive disorder as 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly everyday). A score on the PHQ-9 10 indicates major depression. Scores of 5,10, 15, and 20 represent mild, moderate, moderately severe and severedepression, respectively. The PHQ-9 has high internal consistency (e.g.,alpha ranging from 0.83 to 0.92; Cameron et al., 2008), and correlatesstrongly with other measures of depression (Kroenke et al., 2001). ThePHQ-9 was administered at baseline, the follow-up assessment, andevery other session during treatment.Demographics and Military Service Characteristics Form. TheDemographics Form was developed for all of the STRONG STAR studiesand measures standard information on demographics (e.g., race,ethnicity, gender, age) and military service (e.g., grade, years in mili tary, number of deployments).Head Injury Assessment. A modified version of the Defense andVeterans Brain Injury Center (DVBIC) three-item screening tool wasused to assess history of head injuries and ongoing postconcussivesymptoms (Schwab et al., 2006). Participants were considered to have apositive screen when they endorsed having at least one head injuryduring any of their previous deployments (question 1) and alteredconsciousness for the worst head injury sustained (question 2, itemsA-E).4.2.3. TreatmentCPT (Resick et al., 2007; Resick, Monson, & Chard, 2017) is astructured, manualized treatment in which therapists teach patientsskills to recognize and challenge their dysfunctional cognitions (“stuckpoints”) related to their trauma. In addition to in-session work, CPTpatients complete practice assignments, including progressive work sheets, each day between sessions. After focusing on the most distressingtraumatic event first, patients can work on other traumas as well asovergeneralized beliefs about the consequences of the traumatic eventson their lives.In this study, patients were scheduled for CPT twice weekly. Theycould complete treatment prior to the prescribed 12 sessions if they hada rapid response to treatment, or they could extend treatment beyondsession 12 if good end-state had not been met. If participants neededmore than 12 sessions, they continued to challenge remaining stuckpoints using the same therapy skills. Participants could receive up to 24sessions, but no new worksheets or therapy techniques were added.They continued with their list of stuck points and the last worksheet ofthe protocol. If any crises occurred during the course of treatment, up totwo off-protocol sessions were permitted to address and support thecrisis situation. Examples of crises include death of a loved one, caraccident, arrest, or finding out about being chaptered out of the military.(Galovksi et al., 2012; Resick et al., 2015; Resick, Wachen, et al., 2017;Schnurr et al., 2015).4.2.4. Determination of good end-stateParticipants completed the PCL-5 every other session (i.e., weekly),starting with session one (odd numbered sessions). “Good end-state” wasdefined as a score on the PCL-5 19 and agreement by the participantand therapist that the participant had achieved the therapy goals. Thiscriterion for good end-state was suggested by Schnurr, one of the authorsof the PCL-5 (P. P. Schnurr, personal communication, November 26,2014). If the participant met the PCL-5 cutoff, the therapist andparticipant discussed whether the participant was ready to terminate4

P.A. Resick et al.Behaviour Research and Therapy 141 (2021) 103846treatment. If the patient and therapist decided to conclude treatment,the participant returned in 1 week, completed another PCL-5,1 and had afinal session to discuss treatment gains and receive and review any CPTmaterials not yet covered in the therapy. Even if the end-state criterionwas met, participants could have chosen to continue with treatmentuntil the therapist and participant agreed to end treatment. Theassessment of progress continued every other session. Participants couldreceive a maximum of 24 sessions, but all sessions had to be completedwithin 18 weeks.without reaching good end-state; (5) nonresponders group 2: those whoreached 18-weeks of treatment without reaching good end-state; and (6)ended study participation: those who dropped out by their own decision,or discontinued because of their military responsibilities. We report theproportions classified into each of these outcome categories and providedescriptive statistics including the average and range of the number ofsessions completed in each of these outcome categories.Clinically significant improvement was defined using the ReliableChange Index (Jacobson & Truax, 1991). The RCI is based on the stan dard error of measurement of the difference between two scores fromthe same individual and is a function of the measure’s standard devia tion and reliability. Assuming no real change occurs, the RCI defines acutpoint for statistically significant change that is unlikely to be due tochance fluctuations. In these data, PCL-5 alpha reliability at baselinewas 0.87 and the standard deviation was 12.3, which yields a one-tailed5% cutpoint of 10.2. The smallest integer exceeding that is an 11-pointimprovement, which would be expected to occur by chance 3.8% of thetime if there were no real change.Trajectories of PTSD symptom severity in the five outcome classes(not including the dropouts) were described with sample means. Pre dictors of time to good end-state were analyzed using survival analysismethods. The Kaplan-Meier (product limit) survival curve estimated theproportions of participants reaching good end-

Jun 12, 2020 · et al., 2017). However, response to CPT has been less pronounced in veterans and active duty military personnel than in civilians (Dillon et al, 2017, 2019; Steenkamp et al., 2015). In a recent study of CPT with active duty military personnel, more than half of service members receiving the 12-session