Transcription

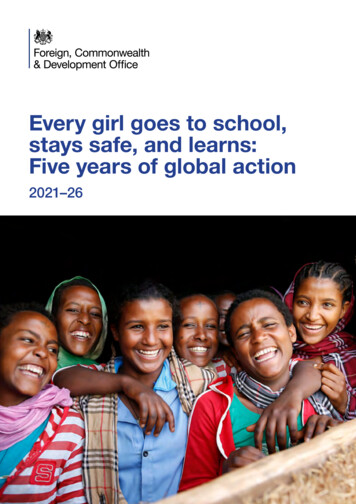

Every girl goes to school,stays safe, and learns:Five years of global action2021–26

Who we areThe Foreign, Commonwealth andDevelopment Office (FCDO) brings theglobal reach of UK’s diplomatic networkand the power of our development expertisetogether to promote the UK’s prosperity,security and values internationally. Nowhereis this integrated approach more importantthat in cementing the UK’s reputation andcompetitive edge as a global leader ineducation as the world recovers from theCOVID-19 pandemic.Our education agenda spans the fulleducation cycle—from providing aid to keepchildren safe and learning in times of crisis,to fostering strategic partnerships betweenthe UK’s world-leading universities andinstitutions overseas; from researching ‘whatworks’ to preparing pre-schoolers to learn,to our fellowships and scholarships that helpdevelop future leaders.At the heart of our education agenda—andcentral to UK action as a force for good inthe world—is our pledge to stand up for theright of every girl around the world to 12years of quality education.Cover photo: School girls in Ethiopia. Credit: Jessica Lea/FCDO

Five years of global action 2021–26 3ContentsForeword. 4Executive Summary. 5Girls’ education is a game changer. 7The scale of the challenge. 9What we’ve learnt. 11The global progress we need to see. 14UK Actions. 16

4 Five years of global action 2021–26ForewordGlobal education is in crisis.COVID-19 has been the largestdisruptor of education in modernhistory. At the height of schoolclosures, 1.6 billion children andyoung people were out of education.Missing out on school does long-termdamage, not only to an individual’s prospects,but to the prospects of their nation. We knowhow disproportionately it affects girls, andthat millions, particularly adolescent girls, maynever return to school after the pandemic.But even before the pandemic, half the world’schildren weren’t on track to read before theyleft primary school. Without remedial support,a further 72 million children may now fallbehind. Unless the world acts quickly, we riska lost generation, with decades of progresswiped out.Education is a human right. It’s also a gatewayto other rights. We need it for gender equality,lasting poverty reduction, and buildingprosperous, resilient economies and peaceful,stable societies. Crucially, it gives children theability to shape their own lives and realise theirpotential.the strength and resilience of communitiesand nations. It is a top priority for the UK.We are putting girls’ education at the heartof our G7 Presidency this year, securing theendorsement of two new milestones to getthe sustainable development goals on track:40 million more girls in school, and 20 millionmore reading by age 10, by 2026, in low andlower middle income countries.With this action plan, we call on theinternational community to renew andrecharge their support for girls’ education overthe next five years. The plan sets out the UK’sdistinct contribution, using all the resourcesavailable to us: diplomatic, financial, and theexpertise to drive this agenda forward.Ambitious targets need ambitious partners.Together, we can advocate for and supportglobal education, particularly for girls, tochange lives, communities, and the prospectsof nations.Girls’ education is a particularly powerfulinvestment, the benefits are wide-rangingenough to stop poverty in its tracks. It isn’tjust a matter of individual fairness; it’s aboutMinister Wendy Morton

Five years of global action 2021–26 5A young Rohingya refugee girl in a UNICEFtemporary learning centre supported by UK aid, inKutapalong, Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh.Credit: Russell Watkins/FCDOExecutive SummaryThe COVID-19 pandemic threatensto undo many of the global gainsof the last two decades in girls’education. As governmentsaround the world build back fromthe crisis and allocate fundsto the highest return activities,the evidence in favour of girls’education and empowermentcannot be ignored, including as anasset in tackling climate change.Yet the crisis in girls opportunities foreducation and learning is not new. Twothirds of the world’s illiterate people arefemale. Even before the COVID-19 struck, astaggering 50% of all school-age childrenglobally were not learning to read by theend of primary school, with girls the clearmajority of out-of-school children. Of thosegirls out of school, more than half (67 million)live in situations of conflict or protractedcrisis. Sadly today, it is millions of poorteenaged girls in Africa and Asia who willpay the highest price of the global educationupheaval wrought by COVID-19—droppingout of school precisely when their prospectsin education were at their brightest.The UK’s response to this set-back—highlighted in the Government’s IntegratedReview1 and set out in detail in this actionplan—will be emphatic. The creation ofFCDO is the springboard for a fully integratedapproach to our international action ongirls’ education. We will bring together ourdiplomatic clout in defending human rightsand the expertise of our ODA programmingfor even greater UK impact as a force for

6 Five years of global action 2021–26Siddika, a ‘little sister’ supported by the Sisters forSisters project in Nepal. Credit: VSO Nepal/Girls’Education Challengegood in the world. We will remain one ofthe largest bilateral and multilateral donorsto global education, returning to spending0.7% of GNI on ODA when the fiscal situationallows.2021 is a year of UK leadership on the worldstage. We will use our G7 Presidency and ourhosting, with Kenya, of the Global EducationSummit in July to bring urgency to the globaleducation recovery, so no girl is left behind.We shall re-double efforts as a champion ofgirls’ education and gender equality, workingon three fronts to:» Shape a renewed international effortto get the 2030 Education SustainableDevelopment Goal on track, obtainingsupport for two milestone targets on girls’school access and learning, trackingprogress relentlessly; and continuingto press for more and better targetedinternational education finance.» Mobilise our network of BritishAmbassadors and High Commissionersto support committed nationalgovernments to scale up efforts to getgirls into school and learning, broadeningand deepening the impact of our Girls’Education Campaign, and conveningpartner governments who have madeprogress to share their experience.» Pioneer global public goods foreducation—developing and usingevidence about what works tosupport governments to make boldreforms, ensuring we deliver better formarginalised girls.Our work on girls’ education is a core pillarof our wider UK support to internationaleducation, spanning early years, primary andsecondary education, to higher educationand skills. We will leverage the UK’scomparative advantage as a world leader oneducation—bringing together our diplomacy,trade, development and soft power, tosupport partner governments, build stabilityand prosperity, and to develop future womenleaders.

Five years of global action 2021–26 7School girls supported by the ENGINE projectin Nigeria. Credit: Mercycorps/Girls’ EducationChallengeGirls’ education is a game changerEducation is a human rightgateway to other rights. It isessential for gender equality,lasting poverty reduction, andbuilding prosperous, resilienteconomies and peaceful, stablesocieties.2There is overwhelming evidence thatinvesting in girls’ education and breakingdown other barriers that they face, canput nations in the development fast lane,especially when women are helped into theworkforce. The recent growth and successof countries in Africa, Asia and Latin Americahas been powered by expanding qualitybasic education for all children, while atthe same time paying special attentionto girls and other disadvantaged groups.Nations have succeeded by making girls’education a national priority rather thanan educational priority.Girls’ education is a smart investmentbecause the benefits are wide-rangingenough to stop poverty in its tracks

8 Five years of global action 2021–26between generations. Quality girls’education, where girls are in the classroomand learning, leads to smaller, healthierand better educated families.3 With justone additional year of secondary school, awoman’s earnings can increase by a fifth.Educated and empowered women can playa massive role in shaping their countries’future. As governments build back fromthe COVID crisis and allocate funds to thehighest return activities4, girls’ educationand gender equality are priorities nocountry can afford to ignore.5More and more, the benefits and costs ofgirls’ education are felt across borders andhave truly global implications. For example,literate girls and women are among thegreatest assets we have in responding tothe climate crisis. Many women and girlsare already leading work to address climatechange. Through quality education more girlsneed to be empowered and equipped asagents of change.Not only is educating and empowering girls asmart investment for all countries, it is also inthe UK’s national interest. Higher standardsof girls’ education globally can help protectthe UK from the consequences of conflict.Studies show that countries with high levelsof gender-based discrimination are morelikely to experience conflict, whereas thosewhere women and men have more fair andequal access to opportunities tend to bestable and peaceful.6None of this means we value boys’education less highly; indeed, the majorityof FCDO’s education work benefits boysas well as girls. We recognise that only byinvolving boys and men can we addressharmful gender stereotypes and improvethe restrictive situation and discriminationholding girls and women back. For instance,teaching that challenges discriminatoryvalues and beliefs and expands children’shorizons is as important for boys as forgirls. But we will measure our success bythe progress made by the girl in the mostchallenging of circumstances; only if sheis thriving in education, will we know we’vedone a good job.

Five years of global action 2021–26 9Fatima is 12 years old. She left Syria in 2012. Shedreams of being a doctor. Credit: Adam Patterson/Panos/FCDOThe scale of the challenge‘The COVID-19 pandemic hasled to the largest disruptionof education ever.’ —AntonioGuterres, United Nations’Secretary General, September2020The COVID-19 crisis has dimmed the hopesof a generation of children and young people.At the peak of school closures in April 2020,1.6 billion learners were out of school across180 countries. Globally, children have missed2/3rds of a school year, and schools in somecountries are still closed.7 Children andparents have experienced upheaval: morechildren are going hungry,8 are experiencingdepression and anxiety,9 and are sufferingfrom violence and abuse.10 One estimatesuggests that five months of learning lossescould result in this generation foregoingearnings equivalent to one-tenth of globalGDP.11 We must act now to mitigate thelasting impacts to individual girls’ andboys’ lives, communities and economiesat large.Girls with disabilities12 and those living inareas affected by conflict13 are likely to beworst affected by school closures. But thedamage is widespread. As many as 24 milliondisadvantaged children (11 million girls) maynot return to school at all 14, with secondaryage girls most at risk of staying home ormarrying early because their families havefallen into poverty. 2.5 million additional childmarriages are expected in the next five yearsand over 1 million adolescent pregnanciesin the next 12 months.15 Rates of genderviolence affecting girls are thought to have

10 Five years of global action 2021–26Adhiambo and her teacher Risper who specialisesin the educational needs of disabled children,Kenya. Credit: Anna Dubuis/FCDOdoubled compared to when schools wereopen16 (i.e. from 8% to 17%).Today, hard-won gains of the last 25years17 are being rolled back. The threatto girls’ futures could not be clearer.Even before COVID-19, 258 million childrenacross the world were out of school, withgirls in Africa and South Asia and in conflictzones lagging furthest behind, especiallyin their chance of getting a secondaryeducation.18 Of the estimated 65 millionprimary and secondary school age childrenwith disabilities, at least half are out ofschool.19But even for those enrolled, for far toomany, schooling isn’t producing learning:half the world’s children, 387 million, werealready not on track to learn to read by theend of primary school. This global crisisin learning has hit low income countrieshardest—with 9 out of 10 children unableto read a story by age 10.20 COVID-19school disruptions may have caused learninglosses equal to the gains of the last twodecades.21 Without remedial action, anadditional 72 million children will fail to learnbasic literacy and numeracy skills.22Increasingly climate change threatensglobal progress towards the SustainableDevelopment Goals for Education (SDG4),Gender Equality (SDG5) and related globaleducation commitments. Globally, at least200 million adolescent girls live on thefrontlines of the climate crisis and thosewho are already marginalised throughpoverty, displacement or disability, are likelyto be worst affected. Climate change impactsare disproportionately felt in developingcountries and girls are doubly disadvantagedbecause of social expectations about theirroles.

Five years of global action 2021–26 11Girls supported by the STAGES project walkingto class in the Bamyan Province of Afghanistan.Credit: STAGES/Girls’ Education ChallengeWhat we’ve learntGender gaps persist in educationat girls’ expense due to the sheernumber of hurdles that stand in agirl’s way.Traditional attitudes restrict women’s rolesand underestimate girls’ learning potential.Physical disincentives, such as longdistances, to the nearest school and lack ofsafe transport. Cost constraints, like buyingschool uniforms, paying exams fees andaccess to even basic technology needed fordistance learning. These challenges differfor different groups of girls. But around theworld girls who are poor, disabled or live onthe margins contend with the most.Problems come up for girls at differentages and stages of her education. Agirl’s place within the family and communitybegins to shift during adolescence whenharmful norms may begin to shape her life,choices and freedoms. Making the movefrom primary to secondary school is oftenhugely challenging for adolescent girls:there are greater responsibilities to care forrelatives or siblings, expectations to earnmoney, have sexual relationships withoutcontraception or get married.Adolescence is when gender gaps inaccess to and attainment in school reallywiden. Yet it is precisely at this time thatgirls stand to benefit most from an educationwhich widens their options and opportunitiesin life. One additional school year canincrease a woman's earnings by 20%. At thistime, teenage girls’ greatest risk of death isfrom complications during pregnancy andchildbirth.23Ensuring all girls gain foundational skills andtruly benefit from education requires all thetools in our toolkit, not only in the educationsector but beyond. In rolling out our 2018Education Policy24 we have learnt that tomake a difference, three strategies must beemployed together:Strategy 1We need to transform what happensin the classroom to improve girls’outcomes—ensuring Government policyand programmes are more inclusive, cantackle multiple sources of disadvantage

12 Five years of global action 2021–26simultaneously and are more flexible tochildren’s diverse needs.In Ethiopia, the UK supports theGovernment to improve the qualityof education for over 1 million children (over50% girls), with particular interventions in upto 18,000 schools, including the mostmarginalised regions of the country. Theprogramme is focused on reducing dropout,particularly girls, pastoralist children andchildren with disabilities, by improving thequality of early years education and raisingthe skills and competencies of 125,000teachers and headteachers.In Zimbabwe, the UK’s support forthe amended Education Act isensuring all girls have a right to education,including in sexual reproductive healtheducation. We are working with theGovernment and communities to ensure girlscan remain safely in school and learn;reducing early marriage, early pregnancy,and violence in school and on route toschool, including through provision ofbicycles and safe boarding whilst at school.In Sierra Leone, the UK isimproving the quality of secondaryeducation for all children, alongside specificmeasures to reduce barriers for girls,including addressing violence in schools. TheGovernment has recently launched the‘Radical Inclusion Policy’, which the UK hassupported, to ensure girls have the right toreturn to school after pregnancy. So far,classroom learning has improved for 1.1million children, leading to 30,000 additionalpass rates in English and maths exams.Double the number of girls now stay inschool compared to 2018, and pastunderperformance of girls compared to boysin final exams has been eliminated.Strategy 2We need to tackle the barriers thatthe most marginalised girls face,particularly during adolescence —whilst we work with Government toensure more inclusive education systems,a more comprehensive package ofsupport is needed to ensure girls learnnow. We need to enable girls to thrivein mainstream education, as well assupporting alternative or non-formaleducation for those outside of themainstream.In Pakistan, alongside support toGovernment education reforms inPunjab and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, the UKhas provided targeted support for over400,000 highly marginalised adolescent girls.This has included provision of secondchance education, scholarships for girls frompoor households to attend secondaryeducation, alongside setting up communityrun schools to reduce the distance that girlsmust travel to school.In South Sudan, the UK is workingwith Canada to remove the financialbarriers to education for up to 400,000marginalised girls, alongside informationcampaigns with parents on the benefits,costs and quality of education to changebehaviours, and encouraging increasedenrolment and attendance in school.In Afghanistan, our girls’ educationchallenge programme co-funded

Five years of global action 2021–26 13with USAID has addressed parents’reluctance to send their daughters to schooldue to the risks of long, dangerous journeysto school through minefields and concernsaround male teachers. Our support across16 provinces has reached over 210,000 girlsand 110,000 boys. Over 7,500 teachers havereceived training and 1,995 young womensupported to attend teacher-training collegeor take apprenticeships, becoming future rolemodels for their communities25.and helped all schools implement schoolre-entry guidelines for girls after childbirth.Strategy 3We need to invest in good teaching—having competent, creative and wellsupported teachers is one of the mostimpactful and cost-effective ways toget girls learning. As countries recoverfrom COVID19, we need to take a freshlook at how to train, recruit and motivateteachers, and support teaching strategiesand policies proven to work well for allpoor and marginalised children, butparticularly for girls.In Malawi, the UK is supporting thegovernment’s national reform of theprimary school maths curriculum; developingnew teaching and learning materials; trainingall teachers nationwide; and establishingongoing school-based support. It builds onprevious UK and US investments to improveearly grade literacy and includes gendersensitive pedagogy (so girls succeed just aswell as boys) and supports children withlearning difficulties and special educationalneeds.In Ghana, the UK has supported theGovernment’s Teacher EducationPolicy reforms, making teaching a degreeprofession for the first time and putting inplace new National Teaching Standards. This‘at scale’ reform has improved teachingpractices of 70,000 student teachers and1500 teacher educators so far. It has also ledto more inclusive and gender-responsiveteaching practices in public teacher trainingcolleges and schools, all 46 teacher trainingcolleges putting in place anti-sexualharassment policies. The UK has alsosupported gender-responsive remedialteaching using distance learning technology,In northern Nigeria, the UK hasbeen working in partnership with theGovernment, TARL Africa and UNICEF toensure schools are ‘teaching at the rightlevel’26 This proven cost-effective remedialstrategy ensures dedicated time for basicskills alongside regular assessment ofstudents’ progress and is now being scaledup across some States in northern Nigeria.

14 Five years of global action 2021–26Girls supported by the Discovery Project in classwith their teacher in Ghana. Credit: DiscoveryLearning Alliance/Girls’ Education ChallengeThe global progress we need to seeProgress towards theEducation Sustainable Goalis at a crossroads. The COVIDpandemic has set back gainsfurther and faster than anyonecould have predicted. At the sametime, the education sector has anopportunity to ‘open up better’,harnessing the impetus of thecrisis to take on new challengesand reassess old ones. Thisopportunity must be seized.With less than 10 years until the SDG4 targetdate of 2030, national governments andthe global community must work togetheras never before to accelerate progress.Governments are looking for evidence ofwhat works to support bold reform thatwill get children learning—and ensure allinvestments, whether home-grown orexternally funded, deliver value for money.

Five years of global action 2021–26 15The UK has pledged to stand up for the rightof every girl to 12 years of quality education;as a champion of girls’ education, and aglobal leader on gender equality, we intendto drive the pace of the global educationrecovery so that all girls benefit. Our aims arestraightforward:» Increase the number of girls aroundthe world who go to primary andsecondary school, reducing the numbersof out-of-school girls,» Improve the quality of education, so allgirls can achieve their potential and breakthe cycle of poverty passing betweengenerations.But broad aims are not enough. Experiencehas shown that time-bound targets help togalvanise international action. As set out inthe UK’s new Strategic Framework for ODA,our focus is to achieve two targets over thenext five years, serving as way-markers onthe road to achieving SDG4. The UK willraise a political rallying call to deliver thesetargets and get SDG4 on track, workingwith partners at all levels—governments,NGOs, the research community andinternational actors. Making progress withthese targets represents an enormouschallenge, demanding new levels ofpolitical commitment and action at bothnational and global levels.Global Targets 2021-2026Access to school: 40 million girls in primaryand secondary school in low and lowermiddle-income countries by 2026.Quality Education: 20 million girls ableto read in low and lower middle-incomecountries by age 10 by 2026.These targets are complementary andmutually reinforcing, each approachingthe challenges for girls from differentangles. While the first focuses on accessto school—closing the enrolment gap forhighly marginalised girls, and at secondarylevel in particular—the second looks at whatskills are required for girls to start well andprogress in education.

16 Five years of global action 2021–26UK ActionsPillar 1:A global coalition on girlslearningThe UK has made a strong contribution togirls’ education over the years by bringingglobal players together and sharing ourunderstanding of what works. We havehelped shift international attention towardsfoundational skills as the critical gatewayto future learning. But the scale of thechallenge ahead defies any singlecountry; it requires an unprecedentedeffort across the whole internationalcommunity.2021 is a year of action for the UK on girls’education. We will use our Presidency of theG7, our co-hosting of the Global EducationSummit—Financing GPE and the UN ClimateChange Conference to shine a spotlight ongirls’ education, making the most of eachopportunity to refresh and revive internationalcommitment and highlight where resourcesare needed most. FCDO Ministers, assistedby the Prime Minister’s Special Envoy forGirls’ Education will spearhead this effort: ourgoal is to agree a new global coalition todrive progress for girls’ education.At the global level we have three priorities:Priority 1Increasing political commitment andinternational leadership on girls’education.We will:» Put the crisis in children’s foundationalskills at the centre of major internationalevents in 2021, securing bold newcommitments, deepening our bilateralpartnerships with like-minded partners,and encouraging other countries toprioritise girls’ education,» Work closely with others to reset andrecharge the global SDG4 SteeringCommittee, anchoring this in the Office ofthe UN Secretary General and involvingpolitical representation,» Shine a spotlight on the clear and presentdanger that climate crisis poses foreducation, and better define the role ofgirls’ education in the global response,» Galvanise international action toovercome the barriers to girls’ accessto education, including through theGeneration Equality Forum and G7commitments to transformative actions,the UN Action Coalition on Gender BasedViolence and UK involvement in FamilyPlanning 2030.

Five years of global action 2021–26 17Beatrice is educating her classmates about familyplanning and avoiding teenage pregnancy inTanzania. Credit: Sheena Ariyapala/FCDOPriority 2Ensure international education financeis better targeted and donor educationODA goes further:We will:» Refocus international education finance,particularly bilateral financing, towards thepoorest countries and basic education,alongside innovative financing thatleverages scarce ODA and makes it gofurther, drawing in the private sector,foundations and non-traditional donors togenerate new sources of finance for girls’education.» Host a successful Global Partnershipfor Education replenishment to raise 5billion over the next 5 years to deliverGPE’s ambitious new strategy, supportingcountries to build back better fromCOVID-19 and accelerating results for themost marginalised girls,» Get new partners on board to support‘Education Cannot Wait’ (ECW) as the keyglobal platform to deliver direct supportfor children whose education has beenaffected by emergencies and protractedcrises, and rally international support forthe Safe Schools Declaration.» As leading supporters of the MultilateralDevelopment Banks, ensure they deepentheir focus on improving learning, includingstrong financial support for secondaryeducation opportunities for girls in IDA,cost-effective and evidence basedinvestments in education technology, andensuring C19 economic recovery supportis gender sensitive, inclusive and targetsthe most marginalised.Priority 3Press for better accountabilityand coordination in the internationaleducation system to deliver thegreatest impact for girls’ education.We will:» Use our diplomatic influence to helpclarify organisational mandates, roles andresponsibilities within the internationalsystem with respect to education andtackling gender related barriers.» Strengthen the capacity of UNESCO’sInstitute of Statistics and the GlobalEducation Monitoring Report to trackand report on global education progress,with a particular focus on disaggregateddata—including extreme poverty, gender,disability, location and other criteriarelevant to each country.

18 Five years of global action 2021–26» Work with like-minded partners todeliver stronger accountability for SDG4progress, including through better use ofeducation data to focus global efforts onareas of greatest need.Pillar 2:Country-led action to get moregirls in school, kept safe andlearningBetween 2015—2019, the UK helped 15.6million children gain a good education, over8 million of them girls through our workdirectly with national governments. Alongsideour support to improve learning in schools,we have led important initiatives to tacklethe obstacles that stop girls going to andremaining in school—from providing safespaces for education in armed conflictsto improving girls’ access to sexual andreproductive health services.There is more we can and must do. In thenext five years we will focus on delivering aset of measurable results which will be theUK’s distinct contribution towards the globaltargets for girls’ education. This will includeambitious UK specific targets to ensure:» More girls in primary and secondaryschool in UK aid-backed countries,reducing the number of out of school girls,» More girls reading by age 10, or by theend of primary school in UK aid backedcountries, and» Girls supported to catch up on learning lossdue to COVID19 disruptions to schooling.We will work closely with UNESCO’sInstitute for Statistics (UIS) as the officialsource of comparable international datafor Sustainable Development Goal 4 to setbaselines and targets, accounting for thedevastating impact of COVID19 on schools,and establishing a robust monitoring systemto account for progress.To meet our UK targets, we will prioritisea broad set of UK led action: includingdeveloping new partnerships andprogrammes at national and regional levels,mobilising our FCDO Ambassadors and HighCommissioners and our network of skillededucation advisers. We will initiate a boldcampaign and communications plan to buildgreater public awareness of and enthusiasmaround the importance of educating girls,

to girls and other disadvantaged groups. Nations have succeeded by making girls' education a national priority rather than an educational priority. Girls' education is a smart investment because the benefits are wide-ranging enough to stop poverty in its tracks School girls supported by the ENGINE project in Nigeria.