Transcription

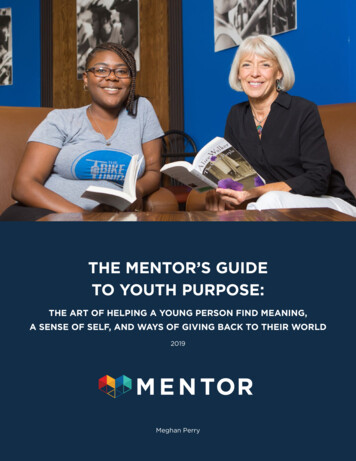

THE MENTOR’S GUIDETO YOUTH PURPOSE:THE ART OF HELPING A YOUNG PERSON FIND MEANING,A SENSE OF SELF, AND WAYS OF GIVING BACK TO THEIR WORLD2019Meghan Perry

TABLE OF CONTENTSSection 1: Understanding Purpose . 1Section 2: Laying the Foundation for Purpose Exploration . 12Section 3: Exploring Purpose Together . 17Section 4: Engaging and Sustaining Purpose Over Time . 21Conclusion . 25Worksheets (separate download)ACKNOWLEDGMENTS T he authors would like to thank the following working group members for lending theirexpertise and experience to the content of this guide: Dr. Kendall Bronk (ClaremontGraduate University); Hana Mangat (founder of Sikh Kid 2 Kid), Steven Rosado (MikvaChallenge); and L-Mani Viney (Kappa Alpha Psi Foundation). D r. Tom Keller (Portland State University) for hosting the Summer Institute on YouthMentoring event that spurred interest in this topic and the development of this resource. C ecilia Molinari for copyediting and Jenni Geiser of Jenni G Designs for graphic design. J PMorgan Chase & Co. for their generous funding of this project and for theirprogrammatic interest in helping young people find purpose in life and the passionto pursue their dreams. MENTOR thanks you for your partnership in this work.

SECTION 1Worksheets used inthis section: Worksheet 1:Deepening Understandingof Purpose Worksheet 2:Unpacking Your PurposeJourney Worksheet 3:Is Mentoring My Purpose?UNDERSTANDINGPURPOSEWe can all benefit from purpose—an intention that supports ourengagement in activities, causes,or contributions that invigorateus, get us planning ahead, andthinking beyond ourselves. Somepeople experience a plethora ofpurpose—a mindset thatreinforces their engagement in arange of meaningful experienceswhile contributing to others—while many others have never,or only occasionally, identified orexperienced opportunities toexplore purpose. Wherever youhappen to be on this spectrum,you found your way to this resource because you care aboutyoung people. And as a caringadult, you can tend to bothindividual and communal wellnessby helping young people connectto and explore their purpose.As a mentor, your empathy,authenticity, and respect inconsistent interactions with ayoung person is shown to supporta wide variety of behavioral,socioemotional, and academicgains.1,2,3,4 And those close,enduring bonds with a youngperson can ripple far beyondindividual outcomes. In this guide,we illustrate how caring adults cansupport interpersonal relationshipswith young people while nurturing their exploration of purpose.Throughout this guide we’llexamine how purpose showsup in a host of contexts andcommunities—ways in whichpeople around the worldcome to understand and valuepurpose as a path to individualand social growth.of purpose has the power tostrengthen relationships andextend benefits of mentoring tofamilies, schools, communities,regions, and even the world. In thefollowing pages you’ll learn aboutthe power of purpose, as well astips to cultivating, engaging, andsustaining youth purpose overtime. While this journey focuseson strategies that center theexperiences of young people,as a mentor, your support ofyouth purpose will require yourown exploration, reflection andparticipation. The more you canbe aware of your own purposejourney or opportunities tobegin such a journey, the betterequipped you will be to supporta young person as they explorepurpose.While nurturing purpose is notrequisite, or even recommended,for all mentoring relationships,modeling engagement inrelevant, stirring experiencesUSING THIS GUIDEThroughout this material you willfind references to several worksheets designed to help integrateIF YOU MENTOR a young person or group of youngpeople in a specific program or youth setting, reach out toyour program coordinator or liaison to talk about opportunitiesfor supporting youth purpose. This guide also offerssupplemental resource, Staff Considerations for Using theMentor’s Guide to Purpose, to help program staff review keyconsiderations to using the information and materials foundhere and to thinking about purpose in the context of aprogram in general.1

awareness of your own purposejourney, so you are betterpositioned to stand alongsideyoung people on a similarjourney. This material is intendedas an iterative workbook,something you can come backto over time instead of readingquickly, cover to cover. Most ofthese worksheets are designed foryour reflection, though, whereverpossible, an asterisk and footnotewithin the worksheet indicate howyou can also adapt the informationto use in direct interactions withyoung people. If you are hopingfor a step-by-step checklist tonurture yours or others’ sense ofpurpose, you won’t find it here—supporting young people inattunement with what makesthem who they uniquely are isnecessarily continual, messy, andpersonal work. But it might bethe most meaningful work amentor can do. If you are up forthe opportunity, read on to learnhow to build your capacity tohelp a young person connect totheir purpose. When’s the lasttime you lost track of time whiledoing something you love? Whenyou were so immersed in anactivity that you could keep goingfor hours? Maybe you had thisexperience while reading a book,cheering on a sports team, orpracticing art. Whatever theactivity, your full immersion inthis kind of experience can bedescribed as flow.⁵ Now consider,when’s the last time youexperienced flow while doingsomething that was not onlyenjoyable to you but alsobeneficial to others? Whenconsidering if something youenjoy is beneficial to others, keepin mind that contribution can beof any scale or significance, andis something that is experiencedpositively.A CASE STUDY – VISUALIZING PURPOSELet’s say you have a friend who really enjoys drawing. She has stacks of drawings she has made over theyears, many sets of colored pencils, a sketchpad always in hand—you get the point. Drawing makes yourfriend feel good and she is really talented. She knows a ton about art, specifically drawing, and lovessharing this knowledge with others. She comes from a long line of artists—her mother creates sculptures,and your friend remembers drawing with her grandfather from an early age. Some of her most prizedpossessions are her grandfather’s drawings. As your friend explains, from the time she was very little, hergrandfather made her feel important when they drew together. He took great interest in what she drew,and commended her choices and vision, letting her know she had a knack for visually depicting herrelationship to the world. This affirmation helped her lean into drawing as a strength. But drawing, shesays, really started to click for her during a challenging period when her grandfather taught her to engagein this activity that she found meaningful to help herself, and by extension others.As your friend recalls, her parents split up when she was three, and she and her mom stayed with hergrandfather for a couple of years. For your friend this was a traumatic, stressful transition when everythingthat was familiar changed. During this time her grandfather had set up a table just her size in front of alarge rectangular window in his living room. He lived in a neighborhood in a small community and fromthat table your friend could watch the goings on of neighbors and the changing seasons in the surroundinglandscape. There was a roll of paper, pencils, and paint always waiting, and she was encouraged to helpherself, whenever she was inclined.2

During this difficult time, when she experienced emotions like sadness, anger, and confusion, her grandfather told her to listen to those feelings. And whenever she was tempted to stop listening or push thosefeelings aside, instead, her grandfather encouraged her to express them through drawing. So she did. Onmornings when she found herself too angry to talk or when she really missed her dad, she sat at the tableand drew and drew and drew. Your friend began to notice that drawing helped her feel better. A few yearslater she connected this coping skill to helping others when her cousin came by for a visit. As your friendexplains, she’s always been close to her cousin who’s just two years older. But one day he came over afterschool too upset to talk. As your friend explains, she connects this seemingly small moment to a new,significant awareness for her: when, without interrogating her cousin or begging him for information, shegently grasped his hand, took him to the table, sat down with him, and said, “Let’s draw.” After about a halfhour of drawing, as your friend recalls, her cousin opened up about getting in trouble for defending one of hisfriends on the playground. In his drawing he depicted the scene from the playground and said he wanted totake it to his teacher to help explain what happened from his perspective. Even as a small child, your friendexplains she learned to see how drawing supported her and others to pay attention to and welcome howthey were feeling. She says she realized at about that time that such a gift was important to share.For your friend, the meaning she found while drawing was also deeply connected to wanting to supportothers in times of stress. She was not exactly sure how, but she knew some day she wanted to leverage herskill to not only draw for herself but to teach others how to use drawing as a source of healing. As was thecase for your friend, people can develop their sense of purpose through multifaceted aspects includingsupportive people (in this case through her grandfather), an awareness of contribution, a propensity ormastery of a specific skill, andmeaningful ionPeople:Contribution:“I know peoplebelive in me.”committment“I am needed.”generosityPURPOSEInternalSOURCESToday, your friend shares herlove for drawing at a communitycenter where she leads a host ofworkshops for people of all sortsof backgrounds, and across thelifespan. Most of her classes arejust as much about supportingpeople to build community as theyare about drawing. For example,one of her drawing circles involveslittle ones ages three to five whoexperience sensory challenges.Another engages elderly adultswith dementia. In these sessions,your friend teaches principles ofdrawing, while also encouragingAbility:Meaning:“I am good at it.”goal direction“I love it.”passionFigure 1: Multifaceted Aspects of Purpose Adapted from Liang., B. (2017).Proceedings from the 2017 Summer Institute on Youth Mentoring, YouthPurpose. Multifaceted Aspects of Purpose, Figure 1: Model of Youth Purpose.Portland, Oregon.3

the incorporation of storytelling, supporting participants to embracecomplex emotions and experiences. In these activities your friend isengaging purpose, an intention unique to her that brings meaning toher life while supporting others.As figure 1 illustrates, purpose involves both a mindset and anengagement in related activities. This means mentors can supportyoung people to explore purpose by nurturing both a young person’sintentional mindset to contribute to others, and by helping them toplug into purposeful pursuits—those opportunities to support othersin ways they find meaningful.DEFINING PURPOSEAs the word implies, purpose is planned intention and involvesengaging in pursuits that are both personally meaningful andbeneficial to others. Kendall Cotton Bronk, a researcher devoted tostudying this concept, describes purpose as a long-term, forwardlooking intention to accomplish aims that are both meaningful tothe self and of consequence to the world beyond the self.8,9Purpose comes from within, and is formed by an individual’sexperiences, interests, and worldview. Since purpose is personal,others cannot impose it. While no one can tell someone else whattheir purpose is, caring people such as mentors can help us identifypursuits that we enjoy, experience a sense of mastery in, and can useto make a meaningful contribution to the world beyond ourselves.To deepen your understanding of purpose, start by reflecting onyour own purpose journey see Mentor Worksheets 1 and 2.Indigenous communities around the world have long understood thevalue of purpose to integrating individual and community well-being.For example, native societies across the Americas have incorporatedabove-mentioned components of purpose in iterations of the medicinewheel, also referred to as the Circle of Courage.10 These traditionsacknowledge the integration of belonging, mastery, independence,and contribution as necessary elements of completeness.11 Similarly, inMaori tradition, a community indigenous to Aoetearoa (New Zealand),exploration of purpose is deeply integrated into processes by whichyoung people learn to take on adult roles in the community.12 In thesetraditions the integration of the following elements (see sidebar) arekey to scaffolding youth sense of purpose.ASPECTS OFPURPOSE IN MAORITRADITIONSPukengatanga:Mentorship characterizedby young person’s role asa “link between generationsthat ensured survival ofcritical knowledge aboutconnections amongpeople, places, and thenatural world” (Stirling &Salmond, 1980 as cited inBaxter et al., 2016, p. 156).Whare Wananga: Schoolsof learning where adultsshare specialized skills andknowledge in areas whereyoung people show interestand propensity (Baxteret al., 2016).Urungatanga:Problem solving throughexperiential learning,or learning throughexposure to real-lifechallenges (Baxteret al., 2016).While these descriptionscome from Maori culture,mentors are well advised tolearn about similar frameworks or ways of understanding purpose that maybe part of a young person’sculture or ethnic background.4

As these indigenous frameworks reveal, purpose has many elements that work together. This meansaspects of purpose can come from a range of spheres to support a person’s overall awareness, exploration,and engagement in purpose. For example, you may know a young person who is affirmed through multiplecaring adults in a pursuit they enjoy, such as reading. You may also notice this young person has not yetbeen supported to connect their enjoyment and aptitude for reading to supporting others. As a mentor,you could help reinforce interrelated elements of purpose by supporting this young person to think abouthow they might explore leveraging their engagement in reading to benefit others—say by volunteering toread to young children or elderly adults.Meaning and purpose are connected, and still important to distinguish. Something is meaningful whenwe experience personal satisfaction or enjoyment from it. Something is purposeful when it is personallymeaningful, beneficial to others, and includes a far-reaching intention.13 From our earlier case study, wecan see how your friend’s contributions evolved over time from benefitting both her and her family, tobenefitting others in her community as well. Similarly, contribution as a component of purpose caninclude benefits to others in immediate relationships (such as family, friends, and colleagues) and thesecontributions might extend benefits to larger spheres, such as organizations in the broader community,institutions, systems, regions, or even the world. It’s up to individuals to determine the focus and scopeof their purpose.WHY PURPOSE MATTERSWith a better understanding ofpurpose, let’s explore the benefits.According to Dr. Bronk (2014)engaging purpose promotes: Well-being Happiness Emotional health Physical health Academic growthTake a look at the components ofpsychological well-being listed inthe sidebar. Of these aspects towell-being, purpose is the mostsignificant to mental health.14, 15Literature suggests, thatengagement in various experiencesas an expression of purpose helpsreduce depressive symptoms.This may be because engagingpurpose helps people experienceand integrate multiple componentsto well-being like self-worth,positive relationships, as wellas experiences of mastery andmattering. The relationshipbetween purpose and improvedmental and emotional health isparticularly important in thecontext of mentoring, as someresearch suggests that nearly40 percent of young peopleinvolved in formal mentoringprograms experience symptomsof depression.16COMPONENTS OFPSYCHOLOGICALWELL-BEING:1. P ositive opinion of yourself(self-acceptance)2. B eing able to chooseenvironments appropriate foryou (environmental mastery)3. W arm and trustingrelationships, and capacity tolove (positive relationships)4. Continually developing yourpotential (personal growth)5. B eing self-determined(autonomy)6. A nd having goals,aspirations, and directionin life (purpose)(Ryff & Singer, 1988)5

Beyond well-being and emotionalhealth, leading a life of purposealso helps foster happinessand life satisfaction.17, 18 When weexperience joy that motivatesus to action and creates personalmeaning, which inspires us to makea difference to others beyondourselves, we are more likely tofeel at peace.19 The enduringaspect of purpose, and a senseof contribution beyond our selves,helps sustain this sense ofcontentment over time.20, 21In addition to well-being andhappiness, engaging in purposeful pursuits also supports a rangeof physical health benefits. Doyou recall the description of flow?When we experience flow, wereduce stress, which leads tospecific health benefits likemproved sleep.22 Evidence alsosuggests that by engaging inpurpose we can reduce thecumulative effect of stress overtime, reducing the likelihood of ahost of negative health outcomesincluding high blood pressure andheart disease.23Finally, research also suggeststhat purpose is associated withmotivation (self-efficacy, selfcontrol) and academic benefits,something that may be ofsignificance in your ownrelationship with a youngperson.24 When young peopleexperience purpose, they alsoexperience increased sense ofcontrol, and research shows apositive relationship between ayoung person’s sense of controlover themselves in theirenvironment and grade pointaverages, specifically amongyouth experiencing economicoppression.25, 26 The long andshort of it is that identifyingand leading purposeful liveshelps all of us thrive.PURPOSE AS A JOURNEYSometimes people assume thatonce you discover a purpose,you’re set. But scholars suggestthat purpose is not stagnant; it iscontinually evolving.27 As a caringadult involved in the life of youngpeople, this will be important tothink about as your relationshipwith the young person changes.Purpose evolves over time becauseit relates to identity, which alsochanges as the years go by.Associated with increased wellbeing, a sense of identity emergesfor people through a flexible yetintegrated sense of self, groundedin socially and culturally relevantvalues and beliefs.28, 29 Similar topurpose, aspects of identity aresaid to be developed throughexperiences of self-worth inassociations with others.30, 31, 32Challenging traditionaldevelopmental theories thatposition identity as a process ofdiscovery, scholar Jackie Regales(2008) suggests processes ofidentity are performed andnegotiated as people exercisefluid yet integrated experiences ofself.33 From this vantage, identityinvolves experiencing personalsignificance both in the momentand over time.34 A multiple, fluidsense of identity suggests thatpeople engage purpose uniquelyin varying domains, and are morelikely to experience satisfaction,when experiences of self arecongruent with experiences of selfin relationship to community.35, 36Like purpose, in Western societies,a sense of identity is oftenexplored through processesrelated to identifying “a calling”—whether that is a calling to be aspecific type of person or a callingtoward a specific kind of activity.37, 38In other words, purpose andidentity are mutually reinforcingas both are grounded in values.Engaging an underlying value tocontribute to others helps peopleexperience belonging andmeaning, thereby allowing us toexpand awareness of who we areand who we want to be. In turn,knowing who we are helps us tobuild intention to supportourselves and others over time.Supporting a young person’s6

experiences of identity andpurpose necessarily involvesreflection and integration of bothindividual and communal values.While exploring purpose ishelpful to all individuals across thelifespan, research illustrates thatit becomes particularly beneficialduring periods of transition.39, 40In between childhood and adulthood, young people experienceincreasing responsibility,autonomy, and opportunities forbelonging, all of which create aperiod of transition where patternsof wellness and emotional healthcome together.41, 42, 43, 44 During thistime young people also encounterincreasing responsibilities relatedto education, employment,housing, and interpersonalrelationships.45, 46 Socioeconomicstatus, family environment, andindividual considerations allcombine to influence youngpeople’s navigation of theseresponsibilities.47 For youngpeople experiencing poverty,adult responsibilities oftenmaterialize earlier and oftenwithout social support andresources.48Exploring purpose can help youngpeople navigate these transitionswhile simultaneously cultivating astrong, affirming sense of identity.Due to their inherent capacityto empower youth voice,The following glossary provides a review of theories and concepts that intertwine with purpose. Keep in mind, this is not an exhaustive list, but reviewingthese related concepts may help you better understand purpose for yourselfand others.Glossary of Terms/Concepts Related to PurposeAdultism: refers to attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors grounded in the assumption that adults are better than young people. It is a form of oppression thatleads to the systematic mistreatment and disrespect of young people.52Autonomy: Experiencing our behavior as directive, and under our control.53Belonging: Feeling like an accepted, valued, legitimate part of a group.54Belonging can be cultivated in relationships when participants recognize“living with and loving other human beings who return that love is the moststrengthening and salubrious emotional experience in the world.”55Competence: Believing that we can positively influence our environment.56, 57Critical Mentoring: Involves utilizing youth and adult relationships to addressinequality—not to manage symptoms, but to address root causes.58Civic Engagement: Civic engagement is multidimensional, including involvement in both political and apolitical experiences. It encompasses individualparticipation in civic spaces including but not limited to institutions, involvement in community groups, or initiatives. Context and cultural experiencesshape understanding of and engagement in community.59Hope: Understanding difficulties within a situation and believing it will improve.60, 61Identity: Being seen and accepted for who we are—which involves recognizing who we are and exploring who we want to be.62, 63Identity and purposeare considered mutually reinforcing.64, 65, 66 Social identity theory suggests thatpeople group themselves in associations with others as a form of self-preservation that helps create self-esteem and self-worth. ,Meaning: A person’s sense that their life experiences are integrated, reinforcing, and of significance.69 Meaning implies something is fulfilling, or satisfying,but does not necessarily include a long-term aspiration or benefit others.70Meaning in life and meaning of life are distinct—here we refer to the former,a sense of meaning in life. Meaning has to do with personal fulfillment, whilepurpose includes personal fulfillment plus contribution, and forward-lookingintention.71 For example, it may be meaningful for you to eat healthy, but doing so does not necessarily contribute to others.Motivation: Involves a combination of abilities, drive, and situational context,and refers to, “internal forces that underlie the direction, intensity, and persistence of behavior or thought.”72, 737

mentoring relationships andsupportive activities have thecapacity to aid young people inthe exploration of both identityand purpose.49, 50, 51PROGRAM FOCUS:CONSIDERATIONS FORSUPPORTING YOUTHPURPOSEIf you are mentoring a youngperson in the context of aprogram, you will likely noticethat the setting has specific goalsand outcomes in mind for youngpeople that also influence the kindof training and support you receivefor engaging with youth.Sometimes program goals alignwith aspects of identity andpurpose for a young person, andoftentimes they do not. You mayfind that program goals andpromised outcomes may evenalienate a young person, or be atodds with their identified purposeand/or identity needs. Too oftenadults are constrained or coachedto focus on outcomes ofimportance to other adults, whileharming interactions with youngpeople in the process. The goodnews is that this tension, thoughoften presented as anoversimplified polarization, canbe attenuated with awarenessof the opportunity to supportresponsivity to unique needs andPassion: Typically associated with a short-lived, intense emotion, passioninvolves “a strong inclination toward a self-defining activity that one likes (oreven loves), finds important, and in which one invests time and energy on aregular basis.”74, 75Relatedness: The need to feel connected and close to others.76 Relates to belonging and the sense that someone claims us and we claim them.77Self-Determination: The perception that one has some control or agency indetermining one’s future. This idea relates to intrinsic motivation, or the desireto do something because we want to, not because we have to, or due to anexternal reward like money. We are said to build positive emotions, and internal motivation when we engage in experiences that contribute to psychological needs of competence, relatedness, and autonomy.78, 79, 80Self-Efficacy: A person’s belief that they can do activities required to attain aspecific level of performance.81, 82 Relates to goal direction and personal relevance components of purpose.Self-Regulation: The process involved in attaining and maintaining goals.83, 84Sparks: Meaningful passions that bring us joy and positive energy. Like purpose, they come from within and can be thought of as initial flames of experience that lead to long-term interests, and talents, and even purpose.85Youth-Adult Partnerships: “Multiple youth and multiple adults deliberating andacting together in a collective [democratic] fashion over a sustained period oftime through shared work, intended to promote social justice, strengthen anorganization, and/or affirmatively address a community issue.”86Youth Voice: Involves supporting young people to actively engage in andinfluence decisions that shape their lives.87, 88circumstances of young people,while also supporting programsustainability and desired outcomes through prioritization ofrelational practice.In other words, it is possible andbeneficial to integrate connectionand compassion inherent ininterpersonal relationships in waysthat reinforce intentionality andgoal direction. As a caring adult,this requires recognition thatconnection and relationship witha young person are the primarygoals. With this awareness, therelationship becomes both thevehicle to desired goals and theend goal itself.90, 91 For moreinformation on components ofrelational practice see section 3.If you are mentoring within thecontext of a program, payattention to how the goals of theprogram sit with young people and8

their families. Try not to gloss overor ignore when aspects of a youngperson’s purpose are in tensionwith broader program goals. Whenyouth purpose and program outcomes are considered a “both/and”instead of an “either/or”, caringadults can support young people tobuild the capacity to nurture themselves and others, while simultaneously rising toward outcomes thatsupport a young person’s thriving invarious communities and contexts.For example, let’s say you mentora young person in a program wherea specific goal of the programinvolves supporting their positiveconnection to an academicenvironment. While engaging withthis young person, let’s say youlearn that they find purpose inactivism related to what theyexperience as systemic racism intheir school culture. At facevalue, it may seem like theprogram goals and this youngperson’s exploration of purposeare in tension. However, if wethink about this situation from ayouth-centered approach thathonors the young person’sexperience and needs, and chooseto view connection with this youngperson as the primary goal, we canstart to envision how, as a mentor,we can support both the youngperson’s exploration of purpose,as well as program priorities inthe following ways:1. Learning about, and supporting the young person to reflect ontheir experiences of discrimination in the school environment.2. W ithout judging, blaming, problematizing or fixing; supporting theyoung person to build awareness of information regardingthe situation including but not limited to:a. History of racism in school, community, and broader socialenvironment.b. Dynamics of power including professional roles, responsibilities,laws, and policies at play in the school environment.c. D escriptive information regarding demographics, outcomes andevidence of opportunities for improvement.3 Supporting the young person to reflect on their feelings related tothe situation. For adults who do not share identities central to ayoung person, particularly if this relates to a young person’s senseof purpose as in the above example, this will likely requiresupporting the young person to conn

Baxter et al., 2016, p. 156). Whare Wananga: Schools of learning where adults share specialized skills and knowledge in areas where young people show interest and propensity (Baxter et al., 2016). Urungatanga: Problem solving through experiential learning, or learning through exposure to real-life challenges (Baxter et al., 2016).