Transcription

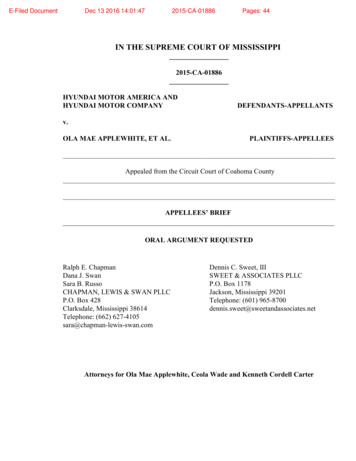

https://doi.org/10.24839/2325-7342.JN25.3.234Using Chapman’s Five Love Languages Theory toPredict Love and Relationship SatisfactionJennifer L. Hughes* and Abigail A. CamdenDepartment of Psychology, Agnes Scott CollegeABSTRACT. Chapman (2015) proposed a popular love language theory aboutcouples’ communication of love. For the present study, we predicted thatpartners who perceived that their partner used their preferred love languagewell would report greater feelings of love and relationship satisfaction. Weexpected this would be the same for both women and men, as well as thosein heterosexual and gay relationships. We recruited 981 individuals incouples to complete online surveys. Using multiple regression, we foundsupport for our hypothesis that a partner’s perception that their partnerwas using their preferred love language well would increase love (i.e., wordsof affirmation R2 .26, quality time R2 .23, gifts R2 .17, acts of serviceR2 .25, and physical touch R2 .24) and relationship satisfaction (i.e.,words of affirmation R2 .32, quality time R2 .24, gifts R2 .11, acts ofservice R2 .20, and physical touch R2 .24). Unexpectedly, we found thatwomen who thought their partners were using their preferred love language(i.e., gifts, acts of service, and physical touch) well reported greater feelingsof love as compared to men. This research provided some support forteaching people in romantic relationships how to learn and use theirpartner’s preferred love languages well. In addition, partners should betaught to recognize when their partners are attempting to use theirpreferred love language because this could lead to increased feelings oflove and relationship satisfaction.Keywords: love languages, couples, love, relationship satisfaction, Chapman,gay couplesCSPECIAL ISSUE 2020PSI CHIJOURNAL OFPSYCHOLOGICALRESEARCH234hapman (2015) proposed that a main reasonfor relationship problems is that couplesspeak different love languages. For couplesto effectively communicate, each partner mustlearn to speak the love language that their partnerprefers. His love languages theory includes wordsof affirmation, quality time, gifts, acts of service,and physical touch.Polk and Egbert (2013) suggested that futureresearch on the love languages should gatherdata on behaviors that partners perceive they arereceiving. For the current study, we followed theirsuggestion and assessed whether the perceptionthat a partner was using a love language wellpredicted love and relationship satisfaction for theother partner. We also evaluated sexual orientationand gender identity as predictors.For this study we used the Love LanguagesProfile written by Chapman (2015) to assess thelove languages. Most research has not used his scale.Instead, the authors developed their own scalesbased on the theory. Bland and McQueen (2018)argued that not using Chapman’s inventory has ledto measurement issues that could have affected theresults of these studies and created mixed results.They also contended that the scale that Chapmandeveloped is conceptually closer to his model ascompared to the scales developed by the otherauthors. Some of those scales also have had poor reliability coefficients (e.g., Bunt & Hazelwood, 2017).In this article, we define the love languagesand give information about how to determine anindividual’s preferred love language or languages.COPYRIGHT 2020 BY PSI CHI, THE INTERNATIONAL HONOR SOCIETY IN PSYCHOLOGY (VOL. 25, NO. 3/ISSN 2325-7342)*Faculty mentor

Hughes and Camden The Five Love LanguagesThen, we review the connection between the lovelanguages and both love and relationship satisfaction. Finally, we review some of the research thathas been conducted on the love languages.Love LanguagesChapman (2015) noted that all five of the love languages are equally important, but that people differon the ones they prefer. The first love languageis words of affirmation. He stated that people wantto be appreciated, and the way partners verballycommunicate this appreciation is important. A softtone is needed, and it is also important to use kindwords and make humble requests. Another way toaffirm a partner is by complimenting the partnerin the presence of friends, family, or coworkers.He argued that complimenting the partner willmake the partner feel loved because their partneris expressing admiration in front of others.The second love language is quality time.Chapman (2015) defined this love language as giving a partner undivided attention, which means thatpartners are doing something together with focusedattention on each other. This attention creates asense of togetherness. A second way to experiencequality time is by having quality conversation. Thisconversation should involve sympathetic dialoguewith partners sharing their experiences, thoughts,feelings, and desires without interruption. He statedthat this type of sympathetic dialogue is crucial forfeeling loved. He also added that quality conversation is different from words of affirmation in thatthe focus is on what the person is hearing from theirpartner rather than on what the person is saying tothe partner.The third love language is receiving gifts.Chapman (2015) found that gift giving is a fundamental expression of love across cultures. Byexchanging gifts, the person is investing in theirrelationship. However, Chapman noted that gifts donot have to cost money; instead, what is importantis that, for some people, gifts feel like a tangiblesymbol of love.The fourth love language is acts of service.Chapman (2015) stated that this involves doingthings that a partner knows their partner would likefor them to do. These acts often involve householdchores. He added that if they are done with positivethought, energy, and planning they can be perceived as expressions of love because they conveythat one partner was thinking about the other.The fifth love language is physical touch.Chapman (2015) argued that it is a powerful wayto communicate love. It can include touching,hugging, holding hands, kissing, or sexual acts.The key is learning the type of touch that is wanted.Determining the Preferred Love Languageor LanguagesChapman (2015) gave several methods in his bookfor discovering a person’s preferred love language.First, he developed the Five Love Languages Profile,which is an online scale that can be used to findpeople’s preferred love languages. This scale wasused in the current research. Another way to finda person’s preferred love language is to ask the following questions: “First, what does your partner door not do that hurts deeply?,” “Second, what haveyou requested that you partner do most often?,”and “Third, how do you regularly express love toyour partner?” These questions allow people to seewhat is important to them and therefore indicates apreferred love language. A third way he suggestedto find a preferred love language involves asking thequestion, “What would an ideal partner be like?”The desired qualities for the ideal partner can beused to pinpoint expectations about desired waysto receive love.Love Languages, Love, andRelationship SatisfactionChapman (2015) proposed that when partnersspeak each other’s preferred love language theywill feel love and greater relationship satisfaction.He suggested that partners have emotional love tanks.An empty love tank can cause romantic withdrawalor falling out of love, harsh interactions, or inappropriate behaviors. Conversely, couples with afull love tank are able to deal with conflict andcope with their differences. Understanding thelove languages, and learning to use the preferredone for a partner, can lead to filling the love tank.Chapman suggested that receiving the preferredlove language is more important for keeping thetank full than receiving a combination of all fivelove languages. He postulated that learning toexpress a partner’s love language often requireseffort and discipline, and when done intentionally,it is most likely to lead to feelings of love and greaterrelationship satisfaction. Problems arise when partners do not know their partners love language(s) orwhen they do not know how to use them. This canlead to the partner instead giving the love languagethey prefer to receive, which might not be seen ascaring and could contribute to decreased feelingsof love or relationship satisfaction for their partner.COPYRIGHT 2020 BY PSI CHI, THE INTERNATIONAL HONOR SOCIETY IN PSYCHOLOGY (VOL. 25, NO. 3/ISSN 2325-7342)SPECIAL ISSUE 2020PSI CHIJOURNAL OFPSYCHOLOGICALRESEARCH235

The Five Love Languages Hughes and CamdenChapman added that partners must recognize whentheir partner is using their love language and thatmiscommunicating in this way can lead to emptylove tanks and dissatisfaction for the couple.SPECIAL ISSUE 2020PSI CHIJOURNAL OFPSYCHOLOGICALRESEARCH236Prior Research Using the Love Language TheoryNot much research has been conducted onChapman’s (1992) love language theory (Bland &McQueen, 2018). Six articles have been publishedin professional journals (i.e., Bland & McQueen,2018; Bunt & Hazelwood, 2017; Egbert & Polk,2006; Goff et al., 2007; Nichols et al., 2018; Polk& Egbert, 2013), one article in an undergraduatejournal (i.e., Cook et al., 2013), and one article waspresented at a conference (i.e., Leaver & Green,2005). In addition, four dissertations have beenwritten about the love languages (i.e., Moitinho,2000; Salas, 2009; Thatcher, 2004; Veale, 2006).Bland and McQueen (2018) grouped theresearch that has been conducted into threecategories. The first category of research includedstudies that evaluated the factor structure of thelove language theory (Chapman, 1992). Threegroups of authors used factor analysis to evaluatethe factor structure of scales they developed toassess the love language theory with mixed results.For example, both Goff et al. (2007) and Cook etal. (2013) evaluated questionnaires they developedto determine people’s love languages instead ofusing Chapman’s (2015) Love Language Profile.Undergraduate students completed their surveys,which also limited the generalizability of their findings. Goff et al. (2007) found six factors includingthe ones Chapman used, but divided acts of serviceinto two groups: domestic service and manual service. However, after completing confirmatory factoranalyses, Cook et al. (2013) did not find factors thatrepresented Chapman’s (1992) five love languages.They noted that future research should instead usethe Love Language Profile developed by Chapman(2015). They believed it might provide the bestevidence for legitimacy of the love languages.The second category of research given byBland and McQueen (2018) included researchthat established evidence for the construct validityof the Love Language model (Chapman, 1992).Egbert and Polk (2006) found that the five factors were correlated with Stafford et al. (2000)relational maintenance typology (i.e., assurances,social networks, openness, positivity, and sharedtasks). Those who scored high on the relationalmaintenance categories also scored high on thelove language factors.The third category of research given by Blandand McQueen (2018) included studies that testedpartners’ preferred love languages and the qualityof their relationships. The current study falls intothis category. As for prior research, Thatcher (2004)and Veale (2006) used the love language theory(Chapman, 1992) and assessed couples’ maritalsatisfaction and love. Neither study supportedChapman’s theory, but Bunt and Hazelwood (2017)noted that these studies had narrow participantpools and methodological flaws. Thatcher’sresearch only examined love language categorymembership but did not look at expressions of thatlove language, which Chapman (2015) proposedto be more important for relationship satisfaction.Polk and Egbert (2013) tested whether partners who express love in ways that align with theirpartner’s primary love language would have morefulfilling relationships. They had couples reporttheir preferred love language using Egbert andPolk’s (2006) 20-item Love Language Scale and didnot use Chapman’s (1992) inventory. The authorswanted to evaluate situations where both partnersreceive their desired love languages, only one partner received the desired love language, or neitherpartner receives the desired love language. To dothis, they categorized each couple based on theirlove language preference and formed matches, partial matches, and mismatches. The most frequentlyoccurring couple type represented a mismatch. Theauthors tested Chapman’s prediction that coupleswho give and receive one another’s preferred lovelanguage experience greater relationship quality.The Quality of Relationships Inventory by Pierce(1994) was used to assess relationship quality. Thisinventory assesses social support and has subscalesfor depth, support, and conflict. They foundthat matched and mismatched couples reportedgreater relationship quality as compared to partiallymatched couples. They stated that their findingsprovided little support for Chapman’s love languagetheory. However, their findings could be a result ofnot using the Love Language Profile developed byChapman (2015). They also used depth, support,and conflict to assess relationship quality, instead oflove and relationship satisfaction, which Chapmanmentioned in his book.For the present study, we predicted thatpartners who perceive that their partner uses theirpreferred love language well would report greaterfeelings of love and relationship satisfaction. Weexpected this would be the same for those inheterosexual and gay relationships, as well as forCOPYRIGHT 2020 BY PSI CHI, THE INTERNATIONAL HONOR SOCIETY IN PSYCHOLOGY (VOL. 25, NO. 3/ISSN 2325-7342)

Hughes and Camden The Five Love Languageswomen and men. However, we did not expect tofind couple type or gender identity to be a predictorbecause relationship quality and satisfaction hasbeen found to be comparable for both women andmen in gay relationships and heterosexual couples(Herek, 2006; Kurdek, 2005; Mackey et al., 2004).In addition, Chapman (1992) proposed that thelove languages were gender neutral and appliedequally to women and men.MethodParticipantsThe 981 participants in this study consisted of520 cisgender women and 461 cisgender meninvolved in heterosexual (346 women, 293 men),lesbian (174 women), and gay male (168 men)relationships who lived in the United States. Nineadditional participants who marked “other” andwrote transgender without specifying the genderthey identified with or agender were not kept inthe data. Because we were specifically looking atparticipants in heterosexual relationships and gayrelationships, we also did not include in the analysesanother 23 participants who marked other andwrote bisexual, pansexual, demisexual, asexual,questioning, queer, fluid, or prefer not to answer.Participants were 18–24 (23.1%), 25–34 (37.9%),35–44 (17.7%), 45–54 (11.7%), 55–64 (7.5%),and over 65 (2.1%). Sixteen participants did notlist their age. Participants listed their racial background as being 72.4% White, 7.5% Hispanic, 7.3%Black, 7.0% Asian, 2.9% multiracial, 1.9% NativeAmerican, or 1.1% other. Four participants did notlist their race. Most participants had attended somecollege (30.8%), had a bachelor’s degree (37.1%),or had a graduate degree (26.4%). All participantslived with their partners, and 45.6% were married.Five participants did not answer the question aboutbeing married. Seventeen percent of participantshad children, and 66.5% of those currently livedwith their parents. The couples reported living withtheir partners for 1–6 months (7.3%), 6–12 months(8.3%), 1–2 years (14.0%), 2–3 years (10.7%), 3–5years (12.7%), 5–7 years (8.7%), 7–10 years (8.7%),and greater than 10 years (29.6%).MeasuresLoveThe components of love (i.e., intimacy, passion,and commitment) were measured using Sternberg’sTriangular Love Scale (Sternberg, 1988). Sternberg(1997) defined intimacy as feelings of closeness,connectedness, and bonding; passion as the drivesthat lead to romance, physical attraction, and sexualactivity; and commitment as the decision to maintain the relationship. The scale has 45 questions.An example item for intimacy is “I have a warmrelationship with my partner,” an example item forpassion is “I find myself thinking about my partnerfrequently during the day,” and an example itemfor commitment is “I am committed to maintainingmy relationship with my partner.” Participants useda 9-point Likert-type scale from 1 (not at all) to 9(extremely). Higher scores indicated greater love.Hendrick and Hendrick (1989) found that all threesubscales demonstrated strong, positive correlationswith the Passionate Love Scale by Hatfield andSprecher (1986) and with Davis’s viability, intimacy,passion, care, and satisfaction subscales and negative correlations with the conflict subscale from theDavis Relationship Rating Form (Davis & Todd,1982). Hendrick and Hendrick (1989) reportedan alpha of .97 when using Sternberg’s scale, andfor the present study, we found an alpha reliabilitycoefficient of .98.Love LanguagesThe Love Language Profile written by Chapman(2015) was used to assess the ways individuals inrelationships communicate including: words ofaffirmation, quality time, receiving gifts, acts of service, and physical touch. Participants were given 30items and asked to pick from two options for each.Participants received a point for each question andthose points were then paired with each of the fivelove languages. The subscale with the most pointswas the preferred love language. Some participantshad two preferred love languages because theirscores tied. Permission to use the scale was receivedby the author of the scale.Partner’s Perceived Use of Love LanguageParticipants were given Chapman’s (1992) definitions of the five love languages. They were thenasked, “When you think about your relationshipwith your partner, how well does your partner dousing the following categories: words of affirmation,quality time, receiving gifts, acts of service, andphysical touch?” Participants used a 5-point scale,poorly to extremely well, for each love language, andthe higher the score corresponded to participantsfeeling that their partner was using their perceivedlove language better.Relationship SatisfactionThe Relationship Assessment Scale is a 7-item measure developed by Hendrick (1988). An exampleCOPYRIGHT 2020 BY PSI CHI, THE INTERNATIONAL HONOR SOCIETY IN PSYCHOLOGY (VOL. 25, NO. 3/ISSN 2325-7342)SPECIAL ISSUE 2020PSI CHIJOURNAL OFPSYCHOLOGICALRESEARCH237

The Five Love Languages Hughes and Camdenitem is “In general, how satisfied are you with yourrelationship?” and participants answered each itemusing a 5-point Likert-type scale from 1 (low satisfaction) to 5 (high satisfaction). Higher scores indicatedgreater relationship satisfaction. This scale has a .80correlation with the longer and more widely usedSpanier (1976) Dyadic Adjustment Scale. Hendrick(1988) found an alpha reliability coefficient of .86for the scale. For the present study, a .86 alphareliability coefficient was also found.SPECIAL ISSUE 2020PSI CHIJOURNAL OFPSYCHOLOGICALRESEARCH238ProcedureAfter IRB approval, 32 research assistants recruited517 individuals who were in relationships (i.e., 234heterosexual women, 122 heterosexual men, 101lesbian women, and 60 gay men) using flyers sentthrough email and posted on social media (i.e.,Facebook). Paper flyers were posted on campusbulletin boards. Another 464 participants (i.e., 171heterosexual men, 112 heterosexual women, 108gay men, and 73 lesbian women) were recruitedusing Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk). Theywere paid 0.50 to participate. We added the use ofMTurk a few weeks after beginning data collectionbecause we worried that we would not get enoughgay men and lesbians as participants, and we lookedat the data and saw that not many participants’preferred love language was gifts. By using MTurk,we widened our participant pool and made it morelikely that our numbers for each love languagewould increase. All participants were asked to takethe same online survey using SurveyMonkey. Tobe considered for the study, individuals had to beinvolved in a relationship, living together, live inthe United States, and had to be able to take thesurvey online.Participants were asked to complete surveysabout the love languages, relationship satisfaction,and love. The surveys also asked about demographicinformation. Participation was voluntary, but boththe convenience sampling participants and theMTurk participants who agreed to participate wereentered in a drawing to possibly win one of four 50Amazon gift cards.Before running our analyses, we compared theparticipants from the convenience sampling andMTurk for the demographics and variables in thestudy. The convenience sample had more women(66.11% as compared to 40.73%) and less racialdiversity (i.e., 3.9% as compared to 10.9% Blackparticipants, 5.85% as compared to 8.17% Asianparticipants, 77.53% as compared to 66.66% Whiteparticipants, .39% as compared to 2.58% NativeAmerican participants), and had more participantswith graduate degrees (31.37% as compared to20.26%). We did not find differences between thesamples for participants being married. Just fewerthan half of the participants from the conveniencesample and MTurk were married.Using Mann-Whitney U tests, we comparedage and length of time together for the couples. We found the convenience sampling group(Mdn rank 519.22) had been together as a couplelonger as compared to the MTurk group (Mdnrank 459.81), U 1057461.00, p .001. However,the samples did not differ when it came to age,U 109795.00, p .139.Using independent-samples t tests, we foundthat love was significantly higher for the convenience sampling group (M 356.36, SD 46.60)as compared to the MTurk group (M 333.25,SD 63.98), t(923) 6.28, p .001, d 0.41, andwe found that relationship satisfaction was alsosignificantly higher for the convenience samplinggroup (M 30.37, SD 4.17) as compared to theMTurk group (M 29.21, SD 4.87), t(947) 3.97,p .001, d 0.26.ResultsThe top preferred love languages were quality time(40.8%) and physical touch (40.0%). The otherlove languages had lower percentages (i.e., words ofaffirmation, 22.7%; acts of service, 13.6%; and gifts,4.0%). Some participants tied for their preferredlove languages and those were represented in thepercentages listed above. Therefore, the percentages exceed 100%.Table 1 contains information about thenumber of participants in each love language andhow well participants felt that their partners wereusing their preferred love language or languages.More than 50% of participants marked that theirpartner was using their preferred love languageor languages well or extremely well for each lovelanguage.Prior to conducting our hierarchical multipleregressions, we tested the relevant assumptions ofthis statistical analysis as put forth by Tabachnickand Fidell (2012). First, our sample size seemedadequate given the independent variables includedin the analyses. The assumption of singularitywas met as our independent variables were not acombination of other independent variables. Anexamination of correlations (see Table 2) revealedthat none of our independent variables were highlycorrelated. Our collinearity statistics, includingCOPYRIGHT 2020 BY PSI CHI, THE INTERNATIONAL HONOR SOCIETY IN PSYCHOLOGY (VOL. 25, NO. 3/ISSN 2325-7342)

Hughes and Camden The Five Love LanguagesTolerance and VIF, were within acceptable limits.Our Mahalanobis distance scores did not indicatethat we had multivariate outliers. Finally, ourresidual and scatter plots indicated that the assumptions of normality, linearity, and homoscedasticitywere met.Because we found differences in our convenience and MTurk samples for love and relationshipsatisfaction, we ran our analyses separately for eachgroup. However, the sample size for gifts was onlythree participants and therefore was too low torun the analyses for that love language. Becauseof this, we decided to run our analyses using thecombined groups.For the analyses, participants were grouped bytheir preferred love language and then hierarchicalregressions were run for each love language. Wefound the following results.For those who had the preferred love languageof words of affirmation, the perception that theirpartners did well with using words of affirmationpredicted greater love (the model accounted for26% of the variance, F[1, 210] 77.50, p .001,95% CI [23.07, 36.38]) and greater relationshipsatisfaction (the model accounted for 32% of thevariance, F[1, 215] 104.31, p .001, 95% CI [2.04,3.01]). Sexual orientation and gender identity werenot found to be predictors for love or relationshipsatisfaction. See Table 3.For those who had the preferred love languageof quality time, the perception that their partnersdid well with spending quality time with thempredicted greater love (the model accounted for23% of the variance, F[1, 376] 112.94, p .001,95% CI [20.73, 30.14]) and predicted greaterrelationship satisfaction (the model accounted for24% of the variance, F[1, 384] 122.59, p .001,95% CI [1.76, 2.51]). Sexual orientation andgender identity were not found to be predictors ofrelationship satisfaction. See Table 4.For those who had the preferred love languageof gifts, both the perception that their partners didwell with giving them gifts and gender identity werepredictors of greater love (the model accountedfor 17% of the variance, F[1, 34] 5.51, p .025,95% CI [3.31, 46.13]). Sexual orientation was notfound to be a predictor. Also, for those who hadthe preferred love language of gifts, the perceptionthat their partners did well with giving them giftspredicted relationship satisfaction (the modelaccounted for 11% of the variance, F[1, 34] 4.46,p .04, 95% CI [.06, 3.27]). Sexual orientation andgender identity were not found to be predictors ofrelationship satisfaction. See Table 5.For those who had the preferred love language of acts of service, both the perception thattheir partners did well with performing acts ofservice and gender identity predicted greater love(the model accounted for 25% of the variance,F[1, 120] 29.31, p .001, 95% CI [15.95, 34.33]).Sexual orientation was not a predictor of love. Also,for those who had the preferred love language ofacts of service, the perception that their partnersdid well with performing acts of service predictedgreater relationship satisfaction (the modelaccounted for 20% of the variance, F[1, 121] 28.79,p .001, 95% CI [1.17, 2.53]). Sexual orientationand gender identity were not found to be predictorsof relationship satisfaction. See Table 6.For those who had the preferred love language of physical touch, both the perceptionthat their partners did well with physical touchand gender identity predicted greater love(the model accounted for 24% of the variance,TABLE 1Percent of Participants Who Felt Their Partners Were UsingTheir Preferred Love Language or Languages Poorly toExtremely WellLove ell6.828.233.626.8Words of affirmation (n 220)4.5Quality time (n 395)1.04.815.437.241.5Gifts (n 39)7.715.425.638.512.8Acts of service (n 129)6.24.721.729.538.0Physical touch (n 385)1.66.213.530.148.6TABLE 2Correlations for the Independent Variables (i.e., SexualOrientation, Gender Identity, and the Perception ThatPartners Are Using the Love Languages Well) and theDependent Variables (i.e., Love and Relationship Satisfaction)Variable1. Sexual orientation2. Gender identity12345678– .03–3. Using words of affirmation well.08* .02–4. Using quality time well.06 .01.45***5. Using gifts well.08* .116. Using acts of service well.037. Using physical touch well–***.32.27***–.01.24***.27***.29*** .04.03.438. Love .05.10**9. Relationship satisfaction . Higher score indicates greater magnitude. All analyses were two-tailed.*p .05. **p .01. *** p .001.COPYRIGHT 2020 BY PSI CHI, THE INTERNATIONAL HONOR SOCIETY IN PSYCHOLOGY (VOL. 25, NO. 3/ISSN 2325-7342)239–.80***

The Five Love Languages Hughes and CamdenTABLE 3Summary of Hierarchical Regression Analysis for Sexual Orientation, Gender Identity, andthe Perception of the Love Language Words of Affirmation Being Used Well Predicting Love andRelationship SatisfactionModel 1VariableBSE BModel 2SE BModel 3βBβ .01 2.374.53 .0410.699.37.09BSE Bβ 5.663.90 .0911.608.04.0929.733.38.52***Predicting LoveSexual orientation .284.15Gender identityUsing words of affirmation wellAdjusted R2F for change in R2 .01 .01.26.011.3077.50***Predicting Relationship SatisfactionSexual orientation.20.31.04Gender identity.23.35.05 .14.71 .02Using words of affirmation wellAdjusted R2F for change in R2 .06.29.01.59.012.52.25.57*** .01 .01.32.42.04104.31*** .01Note. Ns 210 and 215.***p .001.TABLE 4Summary of Hierarchical Regression Analysis for Sexual Orientation, Gender Identity, andthe Perception of the Love Language Quality Time Being Used Well Predicting Love andRelationship SatisfactionModel 1VariableBSE BModel 2βB.05.786.99SE BModel 3βBSE Bβ2.59.02 .872.28 .025.65.079.604.97.1025.442.39.48***Predicting LoveSexual orientation2.322.27Gender identityUsing quality time wellAdjusted R2F for change in R2.01.01.231.041.53112.94***Predicting Relationship SatisfactionSexual orientation.10.18Gender identity.03.05.21.01.24.46.03Using quality time wellAdjusted R2F for change in R2SPECIAL ISSUE 2020.18 .03.43.40.052.13.19.49*** .01 .01.24.32.29122.59***Note. Ns 376 and 384.***p .001.PSI CHIJOURNAL OFPSYCHOLOGICALRESEARCH240 .10COPYRIGHT 2020 BY PSI CHI, THE INTERNATIONAL HONOR SOCIETY IN PSYCHOLOGY (VOL. 25, NO. 3/ISSN 2325-7342)

Hughes and Camden The Five Love LanguagesTABLE 5Summary of Hierarchical Regression Analysis for Sexual Orientation, Gender Identity,

Then, we review the connection between the love languages and both love and relationship satisfac-tion. Finally, we review some of the research that has been conducted on the love languages. Love Languages Chapman (2015) noted that all five of the love lan-guages are equally important, but that people differ on the ones they prefer.