Transcription

Towards MoreTransparentJusticeThe Michael Morton Act’s First Year

The cover image depicts a blue bandanna that was recovered from the vicinity of Michael Morton’s home themorning after his wife, Christine Morton, was murdered.Although no physical evidence connected Michael to thecrime, Michael was charged with and eventually convictedof this offense. Throughout his case, prosecutors withheldother evidence collected during the original investigationthat pointed towards Michael’s innocence. Michael servedtwenty-five years in prison before DNA testing obtained bythe Innocence Project in 2011 of this bandanna clearedhis name and implicated the true perpetrator: Mark AlanNorwood, who was subsequently convicted of this crime.In 2013, the 83rd Texas legislature passed the Michael Morton Act to prevent future wrongful convictions and reinforcepublic trust in the criminal justice system.The authors would like to extend our deep thanks to theInnocence Project for the use of this image.First Edition 2015, Texas Appleseed and Texas Defender Service. All rights reserved, except as follows: Free copies of this report maybe made for personal use. Reproduction of more than five (5) copes for personal use and reproduction for commercial use are prohibitedwithout the written permission of the copyright owners. The work may be accessed for reproduction pursuant to these restrictions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTST exas A ppleseed and the T exas D efender S ervice would like to extend our deep gratitude to our probono partner Locke Lord LLP, for their generous support and the significant research that they undertook for purposes ofthis report on the Michael Morton Act’s implementation. Locke Lord attorneys and staff reviewed discovery policies fromdistrict attorney offices throughout Texas and assisted with additional research and review of this report.In the course of our research, open records requests were sent to every district and county attorney office in Texas. We areappreciative of each office’s cooperation with our work.We also extend enormous thanks to the following individuals who made this project possible: Arthur E. Anthony, Rebecca Bernhardt, Patricia Cummings, Yaman Desai, David Dyer, Deborah Fowler, Amelia Gerson, Steve Hall, Kent Hoffman,Kathryn Kase, Susan Kidwell, Marc Lipscomb, Elizabeth Mack, Amanda Marzullo, Troy McKinney, Mary Schmid Mergler,and Brooks Richmond.TEXAS APPLESEEDTEXAS DEFENDER SERVICETexas Appleseed’s mission is to promote social and eco-Texas Defender Service (TDS) is a nonprofit law firm withnomic justice for all Texans by leveraging the skills andoffices in Houston and Austin. Started in 1995, TDS’ mis-resources of volunteer lawyers and other professionals tosion is to establish a fair and just criminal justice system inidentify practical solutions to difficult systemic problems.Texas, with an emphasis on improving the quality of justice afforded those facing the death penalty. There are four1609 Shoal Creek, Suite 201aspects of our work, each of which seek to advance reformsAustin, TX 78701that impact the criminal justice system as a whole and to512-473-2800establish an indigent defense system in Texas that allowsall those accused of a crime access to competent counsel:www.texasappleseed.net(a) direct representation of death-sentenced prisoners,www.facebook.com/texasappleseed(b) consulting, training, case-tracking, and policy reform@TexasAppleseedat the post-conviction level, (c) consulting, training, andpolicy reform focused at the trial level, and (d) systemicresearch and publication of reports to guide public policy.1927 Blodgett Street510 S. Congress AvenueHouston, TX 77004Suite 304713-222-7788Austin, TX .com/texasdefender@TexDefender

CONTENTSii1913Executive Summary1521273137414345IntroductionThe Michael Morton Act Emerging Issues in the Morton Act’sImplementationRedaction and Withholding PoliciesLaw Enforcement PracticesTiming of DiscoveryDiscovery Conditions & WaiversDisclosure FormatDiscovery DocumentationDiscovery CostsConclusion47AppendicesTOWA RD S M ORE TRANSPAR E NT J U STI CE : THE MI CHAE L MORTON ACT’S FI R S T YE A Ri

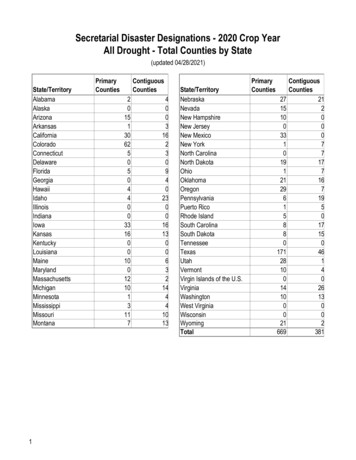

Executive SummaryOJ anuary 1, 2014, the M ichael M orton A ct took effect — markingthe first time in Texas history that criminal defendants have a statutory rightto review the State’s evidence against them without a court order. This enactment instilled transparency into the criminal justice system, and ensured thatthe defense may acquire information necessary to: evaluate the charges againstthe accused, locate and preserve evidence that is favorable to the defendant, andmake an informed decision about how to proceed. The following report is anevaluation of the Act’s implementation during its first year. Its goal is to revealany persistent roadblocks to a defendant’s access to discovery material despite the Act’s passage, and to identifybest practices that may ease the transition process for district and county attorney offices. In preparing ourfindings, Texas Appleseed and Texas Defender Service reviewed written discovery policies established in prosecutor offices and surveyed defense attorneys throughout the State.This systematic overview uncovered a number of issues with the Morton Act’s implementation at the groundlevel. However, none of the concerns raised in drafting this report support the conclusion that further revisionof the Texas discovery statute is necessary at this point in time. Rather, the issues discussed in this report arematters of interpretation and local procedure that should resolve themselves as prosecutors streamline theirprocesses for reviewing and trying cases and as defendants litigate their access to specific materials.nThe Michael Morton Actand Its PassageO utraged over a series of high profile exon erations, the 83rd Texas Legislature passed the Michael Morton Act (S.B. 1611) in 2013, which mandatesopen file discovery processes in criminal proceedings throughout the state. This legislation receivedbipartisan support in both chambers and was drafted in consultation with stakeholders who work innearly every division of the criminal justice system.Its design is to prevent future wrongful convictionsby ensuring that the defense has access to all relevant materials and favorable information necessaryto investigate and prepare its case. A report published by Texas Appleseed and Texas Defender Service in 2013, Improving Discovery in Criminal Casesin Texas: How Best Practices Contribute to GreaterJustice, revealed that the Texas criminal discoverystatute was out of step with best practices promul-iiW W W.T E X AS AP P LES EED. NET . W W W.TE X A S D E FE NDE R .OR Ggated by the American Bar Association and adoptedin a majority of other states. At the time, the defensehad no statutory right to discovery—the exchange ofrelevant materials and information between partiesto a legal proceeding—without a court order. Andwhen issuing discovery directives, trial courts werelimited in the types of disclosures they could mandate. Relevant materials, including offense reports,were not included in the statute’s list of documentsand other tangible things that could be turned overin discovery. While many district and county attorneys went beyond the state law requirements to provide some form of open file discovery to defendants,other prosecutors provided none without a court order, and still others required that defendants waiveother rights in order to receive discovery.The Morton Act leveled the playing field betweenthe prosecution and the defense by implementingmany of the 2013 report’s recommendations. It pro-

vides that almost all relevant, non-privileged material must be provided to the defense “as soon aspracticable” after the prosecution receives a request.The law also contains provisions that protect confidential information. Further, the law requires thatthe State disclose any information that is favorable tothe defense, whether that information is exculpatory(tending to negate the defendant’s guilt), impeaching (grounds for challenging a witness’s testimony orcredibility) or mitigating (supporting a lesser punishment). This obligation to produce such favorable information extends beyond a final conviction.County. The case was particularly distressing becausethe prosecutor who sent Morton to prison had knowingly hidden from the defense evidence that pointedto Morton’s innocence.Redaction & Withholding PoliciesD espite the A ct’s clear mandate that pros ecutors disclose all relevant material that is requestedby the defense, several district and county attorneyoffices withhold broad categories of documents—e.g., medical records—from their disclosures to thedefense or require the issuance of a protective orderbefore they are released. These policies often areBackgroundbased upon arguments of confidentiality, such theAt the time of the Act’s consideration, severphysician-patient privilege, which are inapplicableal high profile exonerations shook the public’s trust inin a criminal proceeding or are rendered without lethe Texas criminal justice system. A study of wrongfulgal force by the means in which the records were obconviction cases in Texas found that nearly a quartertained. The Morton Act’s disclosure requirements,were due to some form of prosecutorial misconduct.codified in Article 39.14(a), are subject only to theMany of these cases were resolved only after the defenexceptions contained in the language of the statutedant spent years, if not decades, in state custody beforeitself—i.e., exceptions for work product, written comtheir innocence was brought to light. For example, Anmunications between prosecutors and other agents ofthony Graves was convicted and held on death row forthe state. Policies that direct line prosecutors to uni12 years due in large part to the testimony of a witnessformly withhold additional material are overly broadwho repeatedly recanted his statements against Gravesand hinder the defense function. While there may beto the prosecutor and whose statements were not disinstances when materials must be withheld to ensureclosed to the defense. Michael Morton, for whom thean individual’s safety, these occurrences are few andfar between. Any subsequent withAt the time of the Act’s consideration, several highholding should be exercised withprofile exonerations shook the public’s trust in thejudicial oversight.Texas criminal justice system. A study of wrongfulIn a similar vein, many officesconviction cases in Texas found that nearly a quarteralso indicated that they uniformlywere due to some form of prosecutorial misconduct.redact information from discoverymaterials in a manner that contradicts the Morton Act. The redactionAct is named, was exonerated in December 2011 afterprocedure established under Article 39.14(c) specificalspending nearly 25 years in prison for the murder ofly provides that any redactions must be limited to inforhis wife. Morton, who had no criminal or violent hismation that is not subject to discovery. Additional retory, steadfastly maintained his innocence from thedactions for information such as the witness’s addressbeginning of the police investigation. After a seriesand date of birth are explicitly prohibited. The Act proof applications to Texas courts, all of which were fertects sensitive information by restricting the defense’svently opposed by the prosecution, DNA testing onability to circulate confidential information provided ina bandanna found near the crime scene exonerateddiscovery and requiring the redaction of specific inforMorton and implicated another individual who is alsomation before showing the material to anyone outsideunder indictment for a subsequent murder in Travisthe defense team (including the defendant).TOWA RD S M ORE TRANSPAR E NT J U STI CE : THE MI CHAE L MORTON ACT’S FI R S T YE A Riii

Moreover, any exceptions to disclosure in the Actdo not apply to information that is favorable to thedefendant pursuant to Article 39.14(h), or the constitutional requirements set out in Brady v. Maryland and its progeny. Favorable information, whether contained in a document or tangible material, orconstituting a mere verbal statement not written orrecorded by law enforcement, must be provided tothe defense at all times. Broad policies for withholding or redacting information must be revised so thatinformation that is subject to disclosure under theAct is consistently provided.Law Enforcement PracticesCoordination between the prosecution andinvestigating agencies is crucial to the full realizationof the Morton Act’s mandate. The Act not only appliesto information that is in the hands of prosecutors butto any information that is in the custody of the Stateor its agents. Yet, many jurisdictions are experiencingissues in the transmission of information betweenlaw enforcement agencies and line prosecutors.Our review revealed that prosecutors’ instructionsto law enforcement agencies, or a lack thereof, may create confusion about law enforcement responsibilitiesunder the Morton Act. Many prosecutors produced noevidence that they had trained or informed local lawenforcement agencies about the Act, or implementedpractices to ensure that law enforcement officers knewwhat must be disclosed in each and every case.Among the jurisdictions that had created memoranda, training materials or new forms and processes,many included information that misstated or diminished the agencies’ obligations. Often these formsemphasized law enforcement’s constitutional obligations under Brady v. Maryland, but ignored the broader requirements of the Act. Other materials developed by prosecutors mischaracterized the obligationsto disclose information under the law. These materials include forms stating that law enforcement’s obligation to disclose information in a case ends with afinal conviction, which explicitly contradicts the Act’sdirective to disclose any favorable evidence before,during or after a case’s resolution.In certain jurisdictions, law enforcement officersivW W W.T E X AS AP P LES EED. NET . W W W.TE X A S D E FE NDE R .OR Gmay be engaging in practices that prevent the prosecution’s full compliance with the Act. Reports fromdefense attorneys also revealed that in a handful ofjurisdictions prosecutors may be disclosing everything in their own files, but not actively encouragingand requiring law enforcement to make sure all relevant information was included in those files.Prosecutors in each jurisdiction must take affirmative steps to educate and communicate with lawenforcement and other investigating agencies to ensure that they understand and comply with the Morton Act. Law enforcement agencies and prosecutorsshould implement practices that require law enforcement to provide to the prosecutor every singlepiece of information collected in a case, leaving it tothe prosecutor to decide whether that informationshould be disclosed to the defense.Timing of DiscoveryThe M orton A ct is clear in its mandate thatprosecutors produce discovery to the defense “assoon as practicable” after a request is received. Thislanguage does not contain any additional conditionnecessary to trigger the discovery process. Yet, several district and county attorney offices in Texas haveestablished policies that are inconsistent with this directive. Most of these policies are problematic in thatthey postpone discovery productions until a formalcharging instrument—i.e., an indictment or information— is filed. Others deny access to certain materialsuntil the eve of trial in contradiction of the plain language of the statute. Under both types of conditions,weeks, if not months, may transpire before a defendant is able to review key materials regarding his orher case. Such policies hobble the defense functionand create inefficiencies in the criminal justice system. Prosecutors should make materials available tothe defense as they become available to the State, regardless of a case’s procedural posture.Discovery-Related WaiversT he M orton A ct ’ s express language providesdefendants with an unqualified right to discovery.Yet, many prosecutor offices have established policies that limit circumstances in which this right may

be exercised—either by requiring that defendantsfices that defendants waive other rights in order towaive the right to discovery in exchange for a fareceive any discovery at all. For example, one officevorable plea, or that defendants forfeit other rightsreported conditioning the right to receive discovin exchange for accessing discovery. Both of theseery on defense counsel’s agreement not to file anyrequirements are contrary to the Act, and are undiscovery-related motions and to forego disclosurelikely to continue as defendants litiof certain categories of evidence, likegate their rights in the proceedingsThe passage of404(b) character evidence. Otheragainst them.further amendcounties ask defendants to waive theThe new discovery rules applyments to Articleright to file discovery motions until awith the same force in cases that do39.14 during thediscovery request has been informaland do not proceed to trial. Moreover,84th legislatively made and denied, or to waive thetheir application to plea bargainedsession, wouldright to certain types of evidentiarycases is essential for full operation oflikely cause moreobjections as a condition of reviewthe Act and the efficient resolutionconfusion anding the information in the state’s file.of cases. The overwhelming majorstymy existing efThese waivers place improper conity—upwards of 95 percent—of feloforts to appropriditions on the defense’s ability to exerny and misdemeanor cases in Texasately implementcise a statutory right. Indeed, the Stateare resolved through pleas of guiltyand comply withBar of Texas recently issued an ethor nolo contendere (no contest). Yet,the 2013 law.ics opinion holding that prosecutorsresearch has conclusively estabviolate the Texas Rules of Professionallished that innocent people pleadConduct if they require such waivers.guilty with alarming frequency. For this reason, itIn light of this opinion, the practice of imposing condiis particularly troubling that prosecutor offices aretions on discovery productions should disappear.asking defendants to waive their discovery rights inexchange for favorable treatment. Given that prosDisclosure Format,ecution in and of itself is a form of punishment, theDocumentation & Coststemptation to plea, coupled with inadequate inforT he M orton A ct does not specify a particu mation regarding one’s case, may lead a number oflar format or method of production. Articledefendants to enter a guilty plea, despite significant39.14(a) provides that discovery may be turnedweaknesses in the prosecution’s case.over by furnishing paper or electronic copies, orMoreover, depending upon their scope, many ofby permitting the inspection of the requested mathese waivers of discovery violate a prosecutor’s ethterial. This flexibility was written into the law inical obligations to produce all information favorableorder to accommodate the differing types of casesto the defense under the Texas Disciplinary Rules ofand the needs and capabilities of different officesProfessional Conduct. Regardless of whether a waivacross the State. Unsurprisingly, prosecutor ofer would be upheld in court, the waivers should notfices have employed a variety of different disclobe used. If the intent of a “waiver” is only to acknowlsure methods during the last year alone, including:edge that discovery has concluded and that the pros(1) cloud-based repositories, (2) email, (3) regularecutor will not produce any additional informationmail or carrier services, (4) in-person only pickthat is not exculpatory, impeaching or mitigating,up, or (5) inspection procedures that allow defensethen documents should state as much without askteams to review files and make their own copies ofing the defendant to “waive” any discovery rights.the material within. Among these delivery mechaA corollary to the requirement by some officesnisms, the exclusive use of the last two will violatethat defendants waive their rights to discovery inthe Act by delaying discovery productions or failorder to plead guilty are requirements by some ofing to produce material altogether.TOWA RD S M ORE TRANSPAR E NT J U STI CE : THE MI CHAE L MORTON ACT’S FI R S T YE A Rv

The Morton Act also codifies the well-establishedprinciple that parties to a legal proceeding should record and document their disclosures. Articles 39.14(i)and (j) provide that the prosecutors must documentthe materials that they produce to the defense, andthat both certify a list of disclosed material to the courtbefore a plea is accepted or the case proceeds to trial.Anecdotal reports indicate that this aspect of the lawis particularly burdensome for prosecutor offices.However, this requirement protects the prosecutorsfrom future allegations of misconduct and foreclosesdisputes about what was produced in post-convictionproceedings which often occur years, if not decades, after a case’s disposition. In addition, there are a numberof means of streamlining the documentation process.For example, electronic discovery systems can beprogrammed to inventory each case and notify thedefense as new materials are added. Other simpletechniques for counties not prepared to implementan electronic discovery system—such as a case indexat the beginning of each file, or the Bates numberingof all discoverable documents—can make the documentation process more efficient.Relatedly, several reports have surfaced about thecost of implementing the Morton Act. While an assessment of the expenses associated with the new lawis beyond the scope of this report, many of the costsassociated with the Act that have been reported areeither one-time initial costs—e.g., purchase of discovery management software—or costs that shoulddecrease as more efficient processes are developed.ConclusionT exas was in dire need of an overhaul of itscriminal discovery statute when the legislaturepassed the Morton Act in 2013. The new law entitlesdefendants to receive a vast amount of material inthe State’s possession, while protecting information that is confidential, privileged or could endanger public safety. Still, a law that changes processesin every single criminal case across the state shouldbe expected to have a steep learning curve. The factthat the Morton Act has caused some confusion andstruggles among those responsible for its implementation should come as no surprise.viW W W.T E X AS AP P LES EED. NET . W W W.TE X A S D E FE NDE R .OR GThe major issues highlighted in this Report—e.g.,failure to disclose certain categories of information,misunderstandings among law enforcement aboutwhat they are required to provide to prosecutors, delays in the provision discovery, and the requirementby some offices that defendants’ waive certain discovery-related rights in the plea process—are vitallyimportant to the full implementation of the law aswell as the fair administration of justice. Yet they arenot necessarily problems with the language of thestatute itself, but rather with interpretations of thatlanguage, or the necessary work and expense relatedto the initial development of an efficient process toimplement the new requirements. None of theseare issues that require an immediate legislative fix.They will likely be resolved in the coming monthsand years through (i) outreach by prosecutors, lawenforcement, defense attorneys and other partiesabout the best practices to ensure defendants haveaccess to relevant information in each case; (ii) education efforts on the part of state associations andagencies, as well as individual prosecutor offices,about what the law requires; and (iii) litigation of issues that continue to go unresolved.The passage of any new legislation during the84th legislative session that would further amendArticle 39.14 would likely cause more confusion andstymy the existing efforts to appropriately implement and comply with the 2013 law. Instead, policymakers should provide practitioners with additionaltime to develop best practices around the new legalrequirements to more fully adhere to both the letterand spirit of the Morton Act.

Introduction[T]here is nothing more vital [to] the reliability and quality of ourIjustice system in Texas than bringing all of the relevant facts to light to ensure we’re protectingthe innocent, convicting only the guilty, and providing justice . . . that we can trust.1M ichael M orton ’ s wrongful conviction due to prosecu tors’ failure to disclose exculpatory information, the 83rd Texas Legislature passed S.B. 1611,known as The Michael Morton Act (“Morton Act”), which was signed into law on May 16, 2013.Designed to instill transparency in the Texas criminal justice system, the bill overhauled the state’scriminal discovery law. Its changes to Article 39.14 of the Texas Code of Criminal Procedure werethe first modifications to this statute since 1965, and by any benchmark, they were long overdue.Before the Morton Act’s effective date on January 1, 2014, the defense had no automatic rightto review and investigate the prosecution’s evidence against the accused. Discovery—i.e. the exchange of relevant information between parties to a legal proceeding—could be obtained only by filing a successful motion “showing good cause” with the presiding court. Even when the motion was granted by the court,defendants and their attorneys gained access to just a portion of the evidence at issue.2nspired by the injustice ofKey materials, including witness statements, expertreports, and the criminal records of the defendantand any co-defendant(s) and witnesses, were excluded from production. Consequently, the defensehad no procedural mechanism to acquire information essential to guard against overcharging, to conduct an independent investigation, and to evaluateevidence likely to be presented to the grand jury oradmitted at trial.1 2Notwithstanding the prosecution’s obligation toproduce favorable information to the defense,3 the soleavenue for obtaining additional insight into the factssurrounding an alleged offense was to appeal to theprosecution to voluntarily supplement its disclosures1. Debate on Tex. S.B. 1611 on the Floor of the Senate, S.J. of Tex., 83rd Leg., R.S. 852-53 (Apr. 11,2013) (statement of the Bill Author, Senator Rodney Ellis) [hereinafter Senate Debate].2. Tex. Code Crim. Proc. art. 39.14(a) (West 2012), amended by The Michael Morton Act, Tex. CodeCrim. Proc. art. 39.14(a) (West 2013).3. Prosecutors have an affirmative duty to produce to the defense evidence that is exculpatory, mitigating or impeaches a witness pursuant to the Fourteenth and Sixth Amendments of the U.S. Constitutionas well as the Texas Disciplinary Rules of Professional Conduct. However, as explained in later sections,these requirements in and of themselves are insufficient to ensure the fairness of the proceedings.beyond the requirements of Texas law. Recognizingthat a transparent discovery process ensures the integrity of case outcomes, some prosecutor offices implemented varying degrees of “open file” policies thatgranted the defense broad access to the prosecution’sfiles.4 Yet, the differences between, and sometimeswithin, district attorney offices created an environment in which the level of information provided to theaccused depended in large part on where the chargeswere brought and the whim of individual prosecutors.5The reliance on the State to disclose materialson its own accord created additional challenges. Although the prosecution has a duty to ensure that justice is served, this duty often is in tension with its obligation to seek convictions in an adversarial system.Hence, crucial information can be withheld from4. Texas Appleseed & Texas Defender Service, Improving Discovery in Criminal Cases in Texas: HowBest Practices Contribute to Greater Justice 21 (2013) (describing open file policies established bythe Galveston and El Paso district attorney’s offices) [hereinafter 2013 Discovery Report].5. Id. at 5.TOWA RD S M ORE TRANSPAR E NT J U STI CE : THE MI CHAE L MORTON ACT’S FI R S T YE A R1

the defense even when the prosecution proceeds ingood faith. Factors such as cognitive bias6 in favor ofthe prosecution’s own theory of the case and heavyworkloads, affect prosecutors’ decision making. Insome cases, prosecutors may even intentionally withhold information that the law would require to be disclosed to the defense. These nondisclosures often remain unknown to the defense; Michael Morton’s caseand other exonerations demonstrate that it frequently takes years, if not decades, after a conviction beforesuppressed exculpatory evidence comes to light.7Recognizing the necessity of limiting prosecutorial discretion to withhold information from thedefense, the Morton Act establishes statewide rulesregarding what is and is not subject to discovery ina criminal proceeding. The defense no longer mustseek a court order to access information in the prosecution’s possession. Rather, the Act requires that theprosecution produce a broad range of informationupon the defense’s request, and codifies the State’sobligation to produce any favorable information regardless of the defense’s request. It also balances thedefense’s increased access to case information withthe safety and privacy interests of witnesses and victims by specifying discovery exemptions, redactionrequirements and restrictions regarding the use ofproduced materials. This framework is a radical advance in the fairness and accuracy of the Texas criminal justice system.However, change takes time. Issues with implementation inevitably occur when the legislatureenacts laws that greatly modify the processes of another branch of government. This report reviews theAct’s implementation during its first year in effect.Its goal is to uncov

TOWARDS MORE TRANSPARENT JUSTICE: THE MICHAEL MORTON ACT'S FIRST YEAR i CONTENTS ii Executive Summary 1 Introduction 9 The Michael Morton Act 13 Emerging Issues in the Morton Act's Implementation 15 Redaction and Withholding Policies 21 Law Enforcement Practices 27 Timing of Discovery 31 Discovery Conditions & Waivers 37 Disclosure Format 41 Discovery Documentation