Transcription

SPECIAL REPORT FEBRUARY 2014Best Practices in Assisted Living:Considering Potential Reformsfor CaliforniaBY ERIC CARLSON AND GWEN ORLOWSKITA B L E O F CO N T E N T SAcknowledgements. 2Executive Summary. 3Introduction. 6Analysis. 8I. Type of Care, and Type of Residents. 8II. Care Standards. 13III. Staff Training and Staffing Levels. 24IV. Resident Rights. 31OverviewBased on a review of assisted living laws ofCalifornia and 11 other states, California’sassisted living policy is significantly out ofdate. An assisted living resident today is likelyto have significant care needs, but California’slaw in general has low standards for quality ofcare. Unlike many other states, California hasnot adjusted adequately to the sharp increasein residents’ care needs over the past 10 to15 years. California’s assisted living law wasenacted in 1985, and has been amendedonly intermittently since then. It requiressignificant revision in order to keep pace withthe new realities of assisted living.V. Accountability. 39Conclusion. 45Citations. 46Development of this report was supported by a grant from the California HealthCareFoundation. The Foundation’s focus is on ideas and innovations that improve quality, increaseefficiency, and lower the costs of care. For more information, please visit www.chcf.org.N AT I O N A L S E N I O R C I T I Z E N S L AW C E N T E R W W W. N S C L C .O R G 1

SPECIAL REPORTAcknowledgementsThe National Senior Citizens Law Center (NSCLC) thanks the California HealthCareFoundation for the funding of this report, and for the Foundation’s public policyfocus on vulnerable Californians.Also, NSCLC thanks the following people for their gracious review of this report’sdiscussion of their states’ assisted living rules: Kevin Brophy, Mike Connors,Jeff Crollard, Kathie Gately, Joelen Gates, Mitch Hagopian, Rick Harris, MitziMcFatrich, Diane Menio, Richard Mollot, Twyla Sketchley, Steve Skipton, and JodySpiegel. Special thanks to Julia Carter for her invaluable assistance with the statespecific research.N AT I O N A L S E N I O R C I T I Z E N S L AW C E N T E R W W W.N S C LC.O R G 2

SPECIAL REPORTExecutive SummaryIntroductionAssisted living facilities offer residentialcare and services for older persons whoare unable to live independently. Someresidents require relatively limited assistance;others require significantly more assistance,and many require health care serviceson an ongoing basis. California has over7,500 facilities with the capacity of housingapproximately 175,000 residents.Assisted living facilities are licensed byindividual states under laws developed bythose states. In California, assisted livingfacilities are licensed as Residential CareFacilities for the Elderly, or RCFEs. Standardsfor these facilities are set by 1985 legislationthat has been amended only on a limitedbasis in the subsequent 29 years. TheCalifornia Department of Social Services(which regulates the facilities) has madesome regulatory amendments, but thosehave not altered the law’s basic framework.Regardless of size, all facilities are governedby the same rules.A recent budget proposal from theDepartment of Social Services describes howCalifornia’s system has failed to keep up withresident’s increased needs:For decades, Assisted Living andResidential Care Facilities for theElderly have been distinguished fromtheir counterparts, [nursing homes],by drawing a bright line between themedical versus non-medical needs ofthe residents. This line has blurred, butthe regulatory structure has not keptadequate pace.As the Department acknowledges, the publicnow expects that assisted living residentswill have access to “health care delivery andmanagement of medical conditions.” TheDepartment states, however, that it has nothad the “resources for policy and regulatorychanges to keep pace with the public’schanging expectations.”Many other states, however, have mademore significant revisions to their residentialcare/assisted living laws in recent years,in an effort to better align those laws withthe greater needs presented by today’sassisted living residents. There is no standardformula. The laws of the individual statesdemonstrate a variety of strategies to balancethe various public policy concerns.Based on an examination of state assistedliving laws from California and 11 otherstates, this report makes the followingrecommendations based on best practicesnoted in those states.RecommendationI. Type of Care, and Types of Residents Levels of Care: California law shouldbe revised to establish a separatelevel-of-care classification for facilitiesthat serve residents with greater careneeds, or in some other way to betterconnect regulatory minimums withresidents’ needs. Care Need Ceilings: Care need ceilingsshould be revised to be less dependenton whether or not a facility chooses tocooperate with an outside agency suchas a home health agency. Optionsshould rest with residents rather thanwith facilities.N AT I O N A L S E N I O R C I T I Z E N S L AW C E N T E R W W W.N S C LC.O R G 3

SPECIAL REPORTII. Care StandardsIV. Resident Rights Service Planning: California law shouldinclude a specific provision requiring acomprehensive service plan, and givinga resident the right to participate inthe plan’s development and to appealunfavorable provisions. Right to Make Everyday Decisions:California regulations shouldincorporate a “person-centered”philosophy that allows facilityresidents to make decisions andexercise preferences. Nurse Participation: Some levelof nurse involvement should beconsidered for incorporation intothe rules governing assessment, careplanning, and service delivery. Visitors: Residents should have a rightto accept visits at any time. Medication Administration:California should establish aregulatory framework for medicationadministration that properly andhonestly balances required expertiseand supervision with the practicalrealities of operating a facility. Evictions: The authorized justificationsfor eviction should be narrowed inorder to give residents more stability. Dementia Care Standards: Trainingstandards should be raised to increasethe expertise of direct-care staffmembers.III. Staff Training and Staffing Levels Training for Direct-Care Staff:Minimum training standards shouldbe increased significantly from thecurrent minimum of 10 hours. Staffing Standards: California’sminimum staffing levels must beincreased in order to be meaningful. Administrator Standards: Californialaw should be revised to require anadministrator generally to be onsite full-time, and to enumeratethe qualifications of a designatedsubstitute when an administrator isabsent. Right to Refuse Treatment: Residentsshould have an explicit right toinformed consent. Restraints: Use of physical or chemicalrestraints should be prohibited. Managing Residents’ Money: Aresident should have timely accessto personal funds held by a facility,and earned interest should be theresident’s property.V. Accountability Frequency of Inspections: Californiashould require more frequentinspections — the current intervalof five years between inspectionsis excessive. Furthermore, theseinspections should not be limited toso-called “key indicators.” Enforcement System: Californialaw should be revised to authorizeper-instance money penalties of ameaningful amount, and to establishintermediate penalties to enable thestate to compel compliance withoutthe need to seek a license’s suspensionor revocation.N AT I O N A L S E N I O R C I T I Z E N S L AW C E N T E R W W W.N S C LC.O R G 4

SPECIAL REPORT Insurance and Bonding: California lawshould be revised to require liabilitycoverage of a meaningful amount. Website Information: Californiashould develop a website that allowsconsumers to find facilities by county,city and zip code. At a minimum, sucha website should provide copies ofinspection reports for the precedingthree years, along with a usablesummary of those inspection reportsfor that period.ConclusionA significant part of the current problemis California’s orientation over the yearstowards maintaining a bright-line separationbetween assisted living and health careexpertise. Other states have searched fora best-of-both-worlds situation in which apleasant environment and a satisfying qualityof life are teamed with competent health careas necessary.vary to a certain extent with circumstances,rather than applying loose, lowest-commondenominator standards across the board.As this report demonstrates, there is no oneright answer. Each state must weigh theoptions and develop its own system. Fortoo long, however, California has abdicatedthis responsibility and failed to addressmany extremely important issues. As soonas possible, the California Legislature andDepartment of Social Services should rectifythis problem and initiate honest discussionabout the pros and cons of various policyoptions. Such a discussion is the necessaryfirst step in bringing California assisted livingpolicy into the 21st century.A defense of the status quo might protestthat the introduction of health care expertisewould convert assisted living facilitiesinto nursing homes. On the contrary,incorporating health care expertise makesit more likely that assisted living care will beadequate, and reduces the chance that aresident will suffer from neglect, or be forcedprematurely to move to a nursing home.A status quo defense also might argue thatadditional standards would be prohibitivelyexpensive for small six-bed facilities withrelatively independent residents, particularlywhen those residents rely on SupplementalSecurity Income (SSI). This type of argument,however, illustrates how a one-size-fits-allmodel can distort public policy. The state’sstrategy should be to develop standards thatN AT I O N A L S E N I O R C I T I Z E N S L AW C E N T E R W W W.N S C LC.O R G 5

SPECIAL REPORTIntroductionBackground and ProblemAssisted living facilities offer residentialcare and services for older persons who areunable to live independently. Some residentsrequire relatively limited assistance withdressing, bathing, or other activities of dailyliving. Other residents, however, requiresignificantly more assistance, and manyrequire health care services on an ongoingbasis. For example, some residents arenon-ambulatory or incontinent, and othersrequire oxygen administration or treatmentfor pressure sores.Assisted living facilities are licensed byindividual states under laws developed bythose states. In California, assisted livingfacilities are licensed as Residential CareFacilities for the Elderly, or RCFEs. Licensingand inspection activities are carried out bythe Community Care Licensing Division of theCalifornia Department of Social Services.Terminology varies from state to state; thesetypes of facilities are variously denominatedas (for example) assisted living facilities,assisted living residences, or personal carehomes. For simplicity, this report in manycases uses the term “assisted living facility”generically, regardless of the state involved.California has approximately 7,500 facilitieshousing a total of 80,000 residents.Standards for these facilities are set by 1985legislation that has been amended only ona limited basis in the subsequent 29 years.The Department of Social Services has madesome regulatory amendments but thosehave not altered the law’s basic framework.Regardless of size, all facilities are governedby the same rules.Particularly in comparison with manyother states, the California regulatorysystem has attempted to maintain a strongseparation between Residential CareFacilities for the Elderly and health care. Ingeneral, facility staff has minimal healthcare training. Instead, for residents withcertain specified health care needs, thesystem relies extensively on care providedby “appropriately skilled professionals”who usually are not facility employees. Forexample, California law recognizes thatresidents may receive necessary care on anongoing basis from visiting home health careagencies or hospice agencies. The relevantlaw sets standards for cooperation betweenthese agencies and facility staff.A recent Budget Change Proposal (Sept. 11,2013) from the Department of Social Servicesdescribes how California’s system has failedto keep up with residents’ increased needs:For decades, Assisted Living and ResidentialCare Facilities for the Elderly have beendistinguished from their counterparts,[nursing homes], by drawing a bright linebetween the medical versus non-medicalneeds of the residents. This line hasblurred, but the regulatory structure hasnot kept adequate pace.As the Department acknowledges, the publicnow expects that assisted living residentswill have access to “health care delivery andmanagement of medical conditions.” TheDepartment states, however, that it has nothad the “resources for policy and regulatorychanges to keep pace with the public’schanging expectations.”Many other states, however, have mademore significant revisions to their residentialN AT I O N A L S E N I O R C I T I Z E N S L AW C E N T E R W W W.N S C LC.O R G 6

SPECIAL REPORTcare/assisted living laws in recent years,in an effort to better align those laws withthe greater needs presented by today’sassisted living residents. There is no standardformula. The laws of the individual statesdemonstrate a variety of strategies tobalance the various public policy concerns.Participation by home health agencies andhospice agencies is common, as are nursingservices and health-related services providedby facility staff.A focused public discussion on these issuesand others is long overdue in California.Unfortunately, the inadequacy of California’ssystem has received very little legislativeattention. Instead, the Department of SocialServices has attempted to keep its headabove water through the occasional revisionof RCFE regulations.MethodologyTo encourage and then facilitate thenecessary policy discussion on theregulation of assisted living in California,this report presents public policy options forconsideration by California lawmakers andother stakeholders. For 19 important issuesin assisted living policy, this report examinesthe relevant assisted living law in Californiaand 11 other states, and concludes with apolicy recommendation. For each of the 19issues, the discussion is supported by tablesthat offer more specifics on each state’sposition. Citations to the relevant provisionsin each state’s law are included at the end ofthis report.in general, have amended their assisted livinglaws in recent years in an effort to keep theirstandards appropriate to the assisted livingpopulation.Wisconsin licenses three different types ofassisted living facilities: Adult Family Homes,Community Based Residential Facilities, andResidential Care Apartment Complexes. Thisreport’s research reviewed the law from allthree types of facilities and, since this reportfocuses on best practices, the report for eachissue includes the provision that best protectsresidents’ interests as the representativeWisconsin provision. The same procedureis followed in states with multiple levelsof care within a licensure category. InFlorida, for example, a provision from the“extended congregate care” level is usedas representative of Florida’s assisted livingfacilities, when that provision is judged to bethe provision of Florida law most protectiveof residents’ interests.Aside from California, the states includedin this report are Alabama, Arkansas,Connecticut, Florida, Kansas, Mississippi, NewYork, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Washington, andWisconsin. They were selected as states that,N AT I O N A L S E N I O R C I T I Z E N S L AW C E N T E R W W W.N S C LC.O R G 7

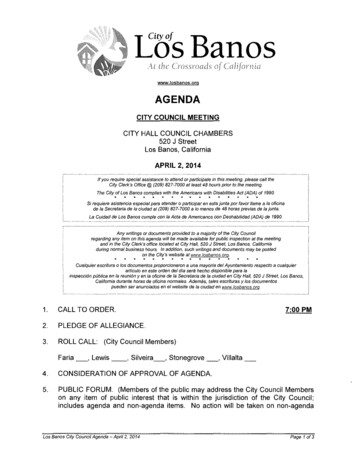

SPECIAL REPORTANALYSISI. Type of Care, and Type ofResidentsLevels of CareCalifornia RulesCalifornia licenses Residential Care Facilitiesfor the Elderly. This is the state’s onlylicensure category for residential care facilitiesthat serve an older population.Other States’ RulesOf the 11 surveyed states, four states offertwo or more levels of care in the licensureof residential care facilities serving an olderpopulation. Arkansas, for example, licensesAssisted Living Level I and Assisted LivingLevel II. Only Level II facilities can admit andretain residents who require a nursing-homelevel of care. Due to the greater needs of theLevel II resident population, the Level II rulesare more demanding.Florida licenses “assisted living facilities” withan option for a licensee to obtain additionallicensure recognition for extended congregatecare, limited mental health, or limited nursingservices. The latter two categories are largelyself-explanatory; the “extended congregatecare” category allows a facility to provideresidents with additional nursing services andmore extensive assistance with activities ofdaily living.Similarly, New York licenses assisted livingwhile giving providers the option of obtainingadditional certification for “enhanced”assisted living, or assisted living with care of“special needs.” Under “enhanced” assistedliving, the facility’s staff is authorized toprovide additional care to meet the needs ofresidents who (for example) need assistanceto walk, are incontinent, or depend uponmedical equipment. “Special needs” facilitiesfocus on care of residents with particularconditions; generally these are facilitiesspecializing in dementia care. (Oversight ofall forms of assisted living in New York hasbeen greatly limited by a court order thathas invalidated certain assisted living rules,on the grounds that those rules exceed thestate’s authority under the state’s assistedliving legislation.)Mississippi licenses two types of facilities:“personal care homes - assisted living”and “personal care homes - residentialliving.” The primary difference between thetwo is that certain health-related services(medication administration, for example) canbe made available in personal care homes assisted living.Seven states (including, as discussed above,New York) have licensure categories ordesignations that focus on residents withdementia. These requirements are discussedin more detail in this report’s section ondementia care standards.Finally, it should be noted that some statesoffer multiple licensure categories thatare distinguished chiefly by factors otherthan level of care. For example, Oregonlicenses both “assisted living facilities”and “residential care facilities,” with thedifference between the two being therequirement in assisted living that livingunits be private, not shared. In Wisconsin,a “licensed adult family home” has threeN AT I O N A L S E N I O R C I T I Z E N S L AW C E N T E R W W W.N S C LC.O R G 8

SPECIAL REPORTLicensure CategorizationRelated to Level of Careto four residents, a “community basedresidential facility” has five or more residents,and a “residential care apartment complex”must offer a lockable entrance, a kitchen, anda private living area and bathroom.Like Wisconsin, many states have licensurecategories specifically for very small facilities.In Washington, an “adult family home” hasno more than six residents. A limit of fiveresidents applies in Florida (adult family-carehome) and Oregon (adult foster home).RecommendationCalifornia law should be revised to establisha separate level of care classification forfacilities that serve residents with greatercare needs, or in some other way to betterconnect regulatory minimums to residents’needs. In California’s current system,too frequently standards are based on alower-common-denominator framework.Consideration of possible revisions hasfocused inordinately on how additionalstandards might affect small facilities withrelatively independent residents, leading tothe too-quick refusal to increase minimumstandards. As a result, many Californiaregulations may be appropriate for low-needsresidents, but are wholly inadequate toensure an adequate quality of care for higherneeds residents.As the above analysis indicates, states employa variety of strategies in order to ensurethat facilities can meet residents’ needs. Adiscussion of this issue is long overdue inCalifornia.OneTwo orLicensure MoreCategory ticutFloridaKansasMississippiNew icensureCategory orDesignationforDementiaCareXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXCare Need CeilingsCalifornia RulesIn California, a facility may not accept orretain a resident who requires 24-hour, skillednursing care, or who depends on othersfor all activities of daily living. Bedriddenresidents may be accepted or retained,subject to certain fire safety rules. A residentmust be able to self-administer medications,though facility staff may assist the resident inself-administration. A person may not residein a facility if his or her primary need for careand supervision results from an ongoingN AT I O N A L S E N I O R C I T I Z E N S L AW C E N T E R W W W.N S C LC.O R G 9

SPECIAL REPORTbehavior caused by a mental disorder thatwould upset the general resident group.In general, a facility cannot accept or retain aresident who has a Stage 3 or 4 pressure sore,a need for gastrostomy care, naso-gastrictubes, a staph infection, or a tracheotomy,although a facility may request a writtenexception if it believes that the resident’shealth-related needs can be met in thefacility. A licensed home health agency mayprovide incidental medical care to residents,but the facility and the agency musthave a written agreement outlining theirresponsibilities to provide certain servicesto the resident. Notably, participation bya home health agency may not expand thescope of care and supervision the facility isrequired to provide.Similarly, a facility may retain a terminallyill resident if the facility obtains a hospicecare waiver from the state, and the residentreceives services from a hospice agency.A care plan between the facility and thehospice agency must limit the facility’s role tothose tasks allowed under the state’s assistedliving rules.Other States’ RequirementsTen of the surveyed states have care-needceilings that limit the acceptance andretention of residents. Generally, theseceilings fall into four categories: a high needfor skilled nursing care; a resident’s inabilityto self-perform activities of daily living or selfadminister medications; serious behavioral ormental health issues; and specified medicalconditions or needs.Nine of the 11 surveyed states prohibit theacceptance or retention of residents whoneed skilled nursing care or around-the-clocknursing care, though a good number of thestates allow for exceptions to the generalrule. In New York, a facility possessing anenhanced assisted living certificate mayretain a resident requiring around-the-clocknursing care when a home care agencydocuments that, with additional nursing andmedical services, the resident can be safelycared for in the facility. Pennsylvania similarlyauthorizes a facility to request permissionfrom the state to admit or retain a residentwith an otherwise impermissible care need.Eight of the 11 surveyed states place somekind of restriction on the acceptance orretention of a resident who is limited in his orher ability to perform activities of daily living.Four states limit residency by persons whoare persistently bedridden; four similarly limitresidency for persons who need significantassistance with transfer; four require thatresidents be ambulatory; and two statesprohibit residency by incontinent persons.Persons who exhibit behavioral issues,require significant mental health services,or are otherwise a danger to themselvesor others may not be accepted or retainedunder the regulations of eight of thesurveyed states. Five of the states limitresidency if physical restraints are required.Wisconsin rules provide that a CommunityBased Residential Facility may accept orretain a resident who is destructive to selfor property, or is physically or mentallyabusive to others, if the facility has sufficientresources to care for the resident, and is ableto protect the resident and others.Five of the 11 surveyed states limit theacceptance or retention of residents withcertain complex medical conditions. Forexample, facilities commonly are notN AT I O N A L S E N I O R C I T I Z E N S L AW C E N T E R W W W.N S C LC.O R G 10

SPECIAL REPORTpermitted to accept or retain residents whohave certain infectious or communicablediseases, or Stage 3 or 4 pressure sores.Care ceilings frequently are based on aneed for certain nursing services, includingtracheotomy suctioning, assistance with tubefeeding, and ventilator dependency.Most of the surveyed states (nine of the 11)permit licensed home health agencies toprovide services to facility residents, oftenso that a resident may remain in a facilityeven as care needs increase. Nine of the11 surveyed states also permit a terminallyill resident, who otherwise has care needsexceeding a care ceiling, to remain in a facilityif a hospice agency can provide neededservices.RecommendationConsistent with other recommendationsfrom this report, care-need ceilings should berevised so they are less dependent on whetheror not a facility chooses to cooperate with anoutside agency (a home health agency, forexample). Consumers would benefit frommore consistency as to what conditions canand cannot be accommodated in a particularclass of facility, and the choice of seeking anexception should rest with consumers ratherthan facilities, to the extent practicable.In contrast to the other states, Oregon by andlarge does not impose mandatory ceilings.Instead, the rules provide involuntarymove-out criteria that authorize a facility,if it chooses, to seek a resident’s eviction.(Eviction is discussed in more detail in aseparate section of this report.)N AT I O N A L S E N I O R C I T I Z E N S L AW C E N T E R W W W.N S C LC.O R G 11

SPECIAL REPORTCare Need CeilingsLimitedbyNeedforSkilledor 24HourNursingCareLimitedByDeficits inActivitiesof DailyLivingLimited asXXXXFloridaXXXXKansasXXXXMississippiXXXXNew YorkXXXLimited ifResidentRequiresPhysicalRestraintsXLimited esCareHospiceCareProvidesCareXXXXXXXX(Level XXXXXXN AT I O N A L S E N I O R C I T I Z E N S L AW C E N T E R W W W.N S C LC.O R G 12

SPECIAL REPORTII. Care StandardsService PlanningCalifornia RulesIn California, a facility must perform apre-admission appraisal, and obtain andevaluate a recent medical assessment. Thepre-admission appraisal at a minimummust include an evaluation of the resident’sfunctional capabilities, mental condition andsocial factors. The facility may use a stateapproved form, at its option.The facility also must meet with the residentprior to admission, or within two weeksthereafter, to develop a written recordof care. The meeting may include theresident’s representative, facility staff, anda representative from the resident’s homehealth agency, if any.The record of care must include the agreedupon services to be provided as well as theresident’s preferences regarding services. Acopy must be sent to the resident’s physician.The record of care must be updated atleast every 12 months, or upon a change incondition.Other States’ RulesAll of the states surveyed, except Mississippi,require a facility to develop a service planprior to admission or soon thereafter. Nineof the surveyed states require that the planbe revised upon a significant change (e.g.,after each hospitalization) or at least yearly;in three states, the service plan must bereviewed more frequently.Generally, a service plan incorporatesinformation acquired through a preadmission medical evaluation and anassessment conducted by the facility. In sixof the surveyed states, a medical evaluation(usually by the resident’s physician) is requiredprior to admission.A pre-admission assessment on a stateapproved form is required in six of thesurveyed states. In Kansas, a nurse, socialworker, or facility administrator must conducta screening, using a screening form specifiedby the state, prior to a resident’s admission.When this screening indicates a need forhealth care services, the resident must befurther assessed by a licensed nurse. Arkansassimilarly requires a registered nurse tocomplete a state-approved assessment whena resident who requires health care servicesseeks admission to a Level II facility. The stateapproved assessment must include, amongother factors, evaluation of the resident’sphysical, mental and emotional health, as wellas social needs and preferences.The resident has the right to participate inthe service planning process in all 10 statesthat require service plans. In most of thesestates, resident participation is protected ina specific section of the rules dedicated toresidents’ rights. Family members, friends,legal representatives and other chosenrepresentatives may participate with theresident’s consent.State rules generally require that the serviceplan address a resident’s need for assistancewith activities of daily living, as well as theother services the resident receives from thefacility. In Arkansas and Connecticut, a serviceplan must reflect the resident’s preferences,needs and choices. Oregon requires a serviceplan to include resident preferences thatsupport principles of dign

as (for example) assisted living facilities, assisted living residences, or personal care homes. For simplicity, this report in many cases uses the term "assisted living facility" generically, regardless of the state involved. California has approximately 7,500 facilities housing a total of 80,000 residents.