Transcription

CO‑OPERATIVESUNLEASHEDDOUBLING THE SIZE OF THEUK’S CO‑OPERATIVE SECTOR

NEW ECONOMICS FOUNDATIONCO‑OPERATIVES UNLEASHEDDOUBLING THE SIZE OF THEUK’S CO‑OPERATIVE SECTORCONTENTSEXECUTIVE SUMMARY 21. OWNING THE FUTURE 62. THE CO‑OPERATIVE APPROACH: A DIFFERENT FORM OF ENTERPRISE 83. CO‑OPERATIVES AS SYMPTOMS AND AGENTS OF SYSTEM CHANGE 114. THE CO‑OPERATIVE ADVANTAGE 125. THE CO‑OPERATIVE ECONOMY TODAY 146. THE UK IN CONTEXT: LAGGING BEHIND 177. THE IMPERATIVE OF NOW: THE OPPORTUNITIES AND CHALLENGESFACING CO‑OPERATIVES 188. CASE STUDIES 239. THE BARRIERS TO CO‑OPERATIVE EXPANSION 2710. THE CO‑OPERATIVE ECONOMY BY 2030 3011. POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS 33ENDNOTES 44BIBLIOGRAPHY 45

NEW ECONOMICS FOUNDATIONCO-OPERATIVES UNLEASHEDDOUBLING THE SIZE OF THEUK’S CO-OPERATIVE SECTOREXECUTIVESUMMARYNow, more than half of UK companyequity is owned abroad and only justover 12% by individuals. The interestsof those who own Britain’s businessesare often misaligned with those ofother stakeholders, such as employees,customers, service users and localcommunities. And even were theyare better aligned, a concentration ofshareholding and the distant power ofcapital markets hollows out the agencyof individual shareholders.For 40 years, the economyhas been a one-waystreet. Assets and equityhave flowed upwardsand outwards, and withthem wealth. MargaretThatcher promised aworld ‘where owningshares is as commonas having a car’. Butthe grand promise of ashare-owning democracy,and with it broad-basedeconomic power, hascrumbled.A different kind of business and, asa result, a different kind of economyis possible, but it will not happenby accident. Co‑operatives are bothjourney and destination in this quest.They are a vector for democraticchange in the economy, and a moredemocratically-owned economicmodel that distributes wealth and isviable today. And yet a lack of policyand support, and a hostile economicenvironment for co-operation in theUK, holds them back.This report is about doubling the sizeof the UK’s co‑op sector. It is also abouthow enterprise can serve the interestsof the people it employs and those inthe communities around them. Andit is about how doing business canincrease economic democracy, and howthe wealth created can be more broadlyand equitably shared.BROKEN ECONOMYBy most measures, the 40-year-oldeconomic model, ushered in byMargaret Thatcher after her electionin 1979, is broken: growth is anaemic;wages and productivity are stagnant orfalling; inequality is stark; investmentis low; consumer debt is high andcrippling; asset bubbles are frequent.The flaws in the neoliberal modelcame to a head 10 years ago duringthe great financial crisis and resultingeconomic crash. Since then, profoundstructural changes have been few2

NEW ECONOMICS FOUNDATIONCO-OPERATIVES UNLEASHEDDOUBLING THE SIZE OF THEUK’S CO-OPERATIVE SECTORand far between. Instead the brokeneconomy has lumbered on zombielike, leading to greater inequality anda growing political tension between arelatively narrow, elite group of winnersand those whose living standards havestagnated.or environmental goal by pooling theresources of a defined group of people.Co‑operatives exist to share risk, powerand reward. They are therefore moredemocratic and accountable forms ofbusiness that, again by nature, cannotsell equity on capital markets andso are beyond the influence of theshareholding conglomerates. Recentstudies have shown them to be moreenduring and resilient in the face ofmarket disruption, more profitable,more productive, happier and longerlasting than non-co‑operative forms ofenterprise.OWNERSHIP MATTERSThis economic malaise and growingsense of injustice is related to thechanging patterns of companyownership and control because whoowns enterprise determines how thewealth businesses create is shared.Powerful, distant shareholdershave presided over a time whenunprecedented levels of wealthcreated have flowed in their directionwhile employees and others haveexperienced a declining share.DOUBLING THE SIZE OFCO‑OPERATIVES IN THE UKIf co‑operatives are better businessesthat can help create a better economy,society and environment, why havethey not thrived in the UK? Andwhy have they thrived elsewhere?To achieve the aim of doubling theturnover of the UK co‑operative sectorby 2030, we must address these twofundamental questions.In addition, ownership shapespurpose. Creating an economy thataddresses the real-world challengeswe face, such as an ageing society orclimate change, and produces goodsand services designed to meet thesechallenges, is immeasurably moredifficult if control lies in the hands ofpowerful shareholding conglomerateswhose habitat is capital markets. Thenew economy mission becomes moreachievable if the power to determinethe direction and strategy of business isin the hands of those with an interestin addressing today’s challenges andwho live in the communities directlyaffected.The answer is not one of rocketscience complexity. Our researchfinds that co‑operatives and thewider cause of democratising andmore evenly spreading the benefitsof enterprise are held back due toan absence of legislation and policy,institutional support, advice, incentiveand promotion. With an economythat does nothing to help co‑opsthrive and everything to create ahostile environment for models ofco-operation, it is unsurprising that theUK has one of the smallest sectors ofany country.THE CO‑OPERATIVE ADVANTAGECo‑operatives are at heart freeenterprises. In the countries in whichthey have thrived, they are oftenrooted in resistance to oppressivegovernment or the march of a marketeconomy that is prejudiced in favour ofan extractive and financialised model.Co‑ops are by nature organisationswith a purpose, and are very oftenestablished to achieve a specific socialIn those places where there isa more significant co‑operativeecosystem (Italy, France, Canada,USA, Costa Rica), there is also – tovarying degrees – a correspondingecosystem of policy and an institutionalarchitecture that helps develop and3

NEW ECONOMICS FOUNDATIONCO-OPERATIVES UNLEASHEDDOUBLING THE SIZE OF THEUK’S CO-OPERATIVE SECTORshelter the co‑operative economy.In the UK this has not hitherto beenthe case. However, there are signs ofimprovement in Wales and Scotland,where non-statutory agencies havebeen established – at a very modestlevel of investment – to encouragethe uptake of co‑operatives. Thoughrelatively young, they show significantsuccess.size. We therefore recommend thatthe Co‑operative Party, which hascommissioned this research andwhich exists to promote the causeof co-operation in policymaking,sets its sights not only on a doublingof turnover, but also on a profoundtransformation in business ownership.One area of focus in Scotland has beenon ‘business succession’; the momentin the development of an enterprisewhen an owner or founder seeks tomove on, often because of retirement.By promoting more democraticforms of ownership at this moment,Co‑operative Development Scotlandhas had significant success in movingbusinesses towards the co‑op model.Based on the findings of our research,we recommend a cohesive programmeof law, policy and institutionalarrangements, including a right toown for employees, a Co‑operativeEconomy Act and a new, statutoryCo‑operatives Development Agency forEngland and Northern Ireland.POLICY RECOMMENDATIONSWe have organised our programme ofrecommendations into five interlockingsteps:New NEF research, published here forthe first time, suggests that there arearound 120,000 family-run small andmedium enterprises in the UK expectedto undergo a transfer of ownership inthe next three years. If just 5% of thesebusinesses were supported to make thetransition to employee ownership orone of the other mutual or co‑operativemodels available in the UK, then thenumber of entities in the sector woulddouble.1. A new legal framework forco‑operatives.2. Finance that serves the co‑operativeagenda.3. Deepening co‑operativecapabilities through a Co‑operativeDevelopment Agency.4. Transforming business ownership.But doubling the number of co‑opsdoes not equate to doubling turnover.The UK co‑operative sector currentlyaccounts for roughly 1% of businessturnover, but around half of thisis achieved by two businesses: theCo‑operative Group and the JohnLewis Partnership.5. Accelerating community wealthbuilding initiatives.We firmly recommend that all fivesteps are taken up with gusto bypolicymakers. It is probable that someform of doubling of UK co‑operativescould be achieved with a moremodest programme. But growth inco-operation and the democratisationof business will likely stall unlesswe transform the hostile economicenvironment into one that is conducive.To double turnover requires furthereffort and almost certainly a cohesiveweb of legislation, support andpromotion. Creating this will inturn almost certainly lead to thedevelopment of a co‑operative sectorthat, perhaps even before 2030, willbe more than double its currentTo this end, we also recommend a‘heartbeat’ policy we call an InclusiveOwnership Fund, which would either4

NEW ECONOMICS FOUNDATIONCO-OPERATIVES UNLEASHEDDOUBLING THE SIZE OF THEUK’S CO-OPERATIVE SECTORcompel or strongly incentivise (or both)all shareholder- or larger privatelyowned businesses to deposit a small,annual share of profits in the form ofequity into a worker-controlled fund.Over time – like a beating heart inthe economy – these funds wouldreach a tipping point, at which timeemployees could opt to take variousforms of control over the running ofthe business.This report was commissioned bythe Co-operative Party, which wasestablished by co-operative societiesand works to provide a political voicefor the sector and to make the case forco-operative approaches in the UKeconomy and wider society.NEF was asked to take undertakean independent examination of thepolicy framework required to meet thechallenge of doubling the size in termsof turnover of the UK co-operativesector. We combined a quantitativeanalysis with a review of relevantliterature. We also conducted detailedinterviews with people across thesector and sought their views throughan online survey, which more than 70people completed.If this sounds radical, then it is onlyas radical as John Lewis because, ineffect, the Inclusive Ownership Fundwould create more businesses asemployee-owned partnerships sharingthe wealth they create and involvingemployees and other stakeholders indecision making and, in particular, indetermining purpose.5

NEW ECONOMICS FOUNDATIONCO-OPERATIVES UNLEASHEDDOUBLING THE SIZE OF THEUK’S CO-OPERATIVE SECTOR1. OWNING THEFUTUREThe UK has the richest region inEurope – inner London – but mostother areas are now poorer than theEuropean average, with poverty rising.The UK’s productivity performance hasbeen abject for a decade, while financeremains overmighty and too distantfrom production.Our economy is markedby deep fissures andlongstanding structuralproblems. In the longwake of the cataclysmicfinancial crisis of a decadeago, UK employeeshave endured the mostpersistent stagnation inearnings for 150 years.Growth in the economyhas not benefited themajority of people andlarge parts of the countryhave yet to see a recovery.Young people for the first time are setto earn less over their lifetime thanthe generation before them. The basicbuilding blocks of life, from housingto education to transport, are costlyand inadequate for many, drivingdestabilising levels of indebtedness.And in our era of hyper-globalisation,value added has shifted from labourto capital, leaving many places andcommunities of people behind asinstitutions of collective agency havebeen hollowed out and democraticpower in the economy weakened.Overarching and reflecting this, weare operating beyond the planet’secological limits as we move deeperinto the Anthropocene, our humanmade era of deepening environmentalcrisis. Unsustainable, inequitable andundemocratic, our economic model isbroken.Addressing these problems will requiremore than tinkering. We will need totransform the economic institutionsthat generate today’s unequal,unsustainable and dysfunctionaleconomic outcomes, such as how firmsare owned and governed. Central tothis must therefore be a 21st centuryenterprise agenda that democratisesthe ownership and control of business.This is because how businesses areowned – who has distributional andcontrol rights within the firm andalso who captures the value they add– vitally shapes how they operate,in whose interests, over what timehorizon, and how they distributetheir profits. In turn this determinesthe nature of enterprise and thedistribution of economic power andreward in society.6

NEW ECONOMICS FOUNDATIONCO-OPERATIVES UNLEASHEDDOUBLING THE SIZE OF THEUK’S CO-OPERATIVE SECTORCrucially, though there are manypurposeful businesses in the UK, oureconomy faces structural challengesthat are rooted in the dominanceof private, investor-led, extractivemodels of business ownership andmanagement: the short-termism indecision-making it engenders, and itsrelationship to our poor productivityand investment performance; thelack of control most of us have overthose decisions, despite the UK’s weakrecord on management performance;and the inequality and insecurity itpromotes, including in the stewardshipof common but finite natural resources(Co‑operative Party 2017; LabourParty 2017). As Marjorie Kelly puts it,‘ownership is the gravitational fieldthat holds our economy in its orbit,locking us all into behaviours thatlead to financial excess and ecologicalovershoot’ (Kelly 2012).the UK’s dysfunctional land market. Ifcapital was broadly owned, this wouldbe less of a problem. However, thewealthiest 10% of households own45% of the nation’s wealth, five timesmore than the bottom half, and almost70% of financial wealth, includingstocks and shares (ONS 2018a). Thenarrow ownership of economic assets,including business equity, in a timeof rising capital income is thereforelikely to drive rising inequality withoutredistribution of ownership.At the heart of any enduring economictransformation must therefore be thedevelopment of a new architectureof democratic ownership. Piecemealreform that leaves current modelsof ownership and the distribution ofeconomic assets untouched will leavethe fundamental values and operationof our economic system unchallenged.In place of extractive, disconnected andshort-termist forms of ownership, wehave to build forms of ownership thatare distributive by design, generativein purpose, democratic in orientation,and have a sense of connection to place(Raworth 2016).The primacy of shareholders in ourlargest companies excludes workersand consumers from exercisingcorporate governance rights andincentivises short-termist andextractive business behaviour. Thoughbusinesses are institutions that bringtogether capital and labour for thepurpose of production, involvingpolitical relationships of controland the exercise of authority, capitalis sovereign and labour withoutgovernance rights in our dominantbusiness models. Unsurprisinglythen, the UK comes near the bottomof OECD economies in terms of theextent to which patterns of ownershipand business forms support economicdemocracy (Cumbers 2016).1There is no single step that canachieve this. What is required is apluralistic and proactive strategy toscale alternative models of ownershipthat can reorientate enterprise towardsthe common good, shape productiontoward democratic needs, stemfinancial leakage and build a futureof shared economic plenty by sharingthe rewards of our collective economicendeavours. Co‑operatives – a triedand tested means of democratisingand equitably sharing the benefits ofenterprise – must be at the heart ofthis.At the same time the distributionand nature of business ownership isa critical factor in inequality. Capital’sshare of national income has risenover time, and is likely to rise further,driven by trends such as increasingautomation, the rise of platformwinner-take-all ‘superstar firms’, and7

NEW ECONOMICS FOUNDATIONCO-OPERATIVES UNLEASHEDDOUBLING THE SIZE OF THEUK’S CO-OPERATIVE SECTOR2. THE CO‑OPERATIVEAPPROACH: ADIFFERENT FORM OFENTERPRISEFrom their origins as a form of mutualself-help in response to the hardshipsand exploitation of the IndustrialRevolution, co‑operatives have applieddemocratic, collaborative processesto economic organisation. They areowned and democratically run bythe people who work and use them.Their ownership structure aims toensure people – whether producersor consumers – have a genuine,democratic stake in their enterprise,and share in the wealth they create.By putting genuine control in thehands of workers or consumers,not the providers of capital, withformal equality among members interms of economic decision making,co‑operatives embody a different visionof how power should be organisedand used in economic activity, one thatinstitutionalises justice in production(Hsieh 2007).The InternationalCo‑operative Alliancedefines a co‑operativeas an ‘autonomousassociation of personsunited voluntarily to meettheir common economic,social, and cultural needsand aspirations througha jointly-owned anddemocratically-controlledenterprise’ (ICA 2018). Assuch, they are a form ofenterprise in common,rooting ownership,control and benefitswith the members andbeneficiaries of theco‑operative, not externalinvestors.From their emergence in Rochdale in1844, co‑operatives have been basedon shared values, driving co‑operationto meet common needs. These valuesremain central to co‑operation today:self-help, self-responsibility, democracy,equality, equity and solidarity. Theseven foundational principles of theco‑operative movement provideguidelines for practical action torealise those values: voluntary, openownership; democratic owner control;owner economic participation;autonomy and independence;education, training and information;co-operation among co‑operatives; andconcern for the community.Co‑operative membership is voluntaryand open to anyone who can benefit.Democratic control rests with theco‑operative’s members based on onemember one vote, regardless of capitalcontribution, and there are limitedreturns on capital. An emphasis isplaced – cultural and operational –on co‑operative autonomy and thecollective development of the capacityof ordinary people independent of both8

NEW ECONOMICS FOUNDATIONCO-OPERATIVES UNLEASHEDDOUBLING THE SIZE OF THEUK’S CO-OPERATIVE SECTORcapital and the state. Co‑operativesalso seek to deepen wider co‑operativeculture, stressing the importance ofnon-market values as well of differentvalues for acting in markets than profitmaximisation, through educationamong co‑operators and the widercommunity.a co‑operative, compared to thetransactional and more fluid financialparticipation of a shareholder in acompany, as Labour’s independentAlternative Models of Ownershipreport argued (2017). Another relateddifference is that while shareholdersown the entirety of the value ofthe company, the membership ofa co‑operative only has a sharedclaim via common ownership, witha core part of the underlying captialremaining locked and not claimable bythe members. Members consequentlygive up an element of influenceand financial gain for the benefitof the membership collective. Thisreflects the differing purposes of theorganisations: a company exists forthe private benefit of its shareholders,whereas a co‑operative is trading forthe benefit of its members (Malleson2012). The co‑operative is a dynamicself-help mechanism enabling peopleto collectively meet their shared needsin a broader social context.Co‑operatives are consequentlyradically distinct from capitalistfirms in organisation and purpose,producing very different outcomes.They are not simply a nicer form ofeconomic organisation. The right ofcapital is replaced by the sovereigntyof collective membership. They areowned differently, governed differently,and operate differently; their risk isshared differently and the rewards aredistributed differently.Co‑operatives exist to serve andservice the needs of their members.Direct control and ownership lieswith the members and beneficiariesof the co‑operative. Members ofa co‑operative are all equal anddetermine democratically theco‑operative’s policies and practices.This contrasts with the membershipof a company, where control rightsare in proportion to the number ofshares owned and shareholders areassigned first and overriding priorityin the governance of the business overother stakeholders, at least in AngloAmerican corporate governance.As a form of common democraticownership, any surplus generated bythe co‑operative is returned to theco‑op’s members through dividends orlower prices, or otherwise reinvestedin the co‑op, held in reserves, or usedfor some other social purpose, all inaccordance with the wishes of themembers. This reflects their differingpurpose: to provide for the needs oftheir members rather than maximiseprofit for external shareholders,embedding the principle of aneconomy that puts people beforeprofit in their organisational fabric. Assuch, they are fundamentally social inorientation, a form of ‘enterprise for thecommon good’ (Alcock and Mills 2017).Although both a co‑operative anda company are enterprises, in aco‑operative people come togetheras equals, and strive collectively andcollaboratively to achieve the businessaim together; whereas a company is amechanism for operating a businesswhose ownership and control is opento whoever is able and willing toacquire it regardless of their objectivesor incentives (Alcock and Mills 2017).In an era of often deliberately rootlessownership – as capital seeks to cutcosts and exposure to redistributionalobligations (ie taxation) – and sharpeconomic inequalities of place,co‑operatives are mostly anchoredin their localities. They act to serveMembership is consequently amore committed relationship in9

NEW ECONOMICS FOUNDATIONCO-OPERATIVES UNLEASHEDDOUBLING THE SIZE OF THEUK’S CO-OPERATIVE SECTORtheir members and whatever profit isgenerated is retained in the locality oramong members; they generate andkeep wealth in communities, whethergeographic or membership-based. Indoing so, by pooling talent, resourcesand interests together for the benefitfor the membership, rather thanexternal investor-owners, co‑operativesare ‘a direct manifestation of socialistprogression’ (Hunt and Willets 2017).in UK law that form part of the sector,the critical defining characteristic ofco‑operatives is that they are, in thewords of Co‑operatives UK, ‘run notby institutional investors or distantshareholders, but by their members.People like you and me – customers,employees, residents, farmers, artists,taxi drivers’.2 (Co‑operatives UK2017c). Whatever the co‑operativeform, the objective remains the same:to capture the value added by doingbusiness within a defined communityrather than opening it up for extraction.The legal and institutional frameworkof co‑operatives consequentlymake them purposeful by design,established to serve specific needsand populations, generating beneficialsocial and economic outcomes in theprocess. There are typically five types ofco‑operative in terms of membership:There are therefore strong argumentsfor a large and broad-basedco‑operative sector. Nevertheless,because it has received so littleattention and support, the UKco‑operative sector across this wholespectrum remains small. Much moreincentive, support and encouragementis therefore needed now for thosewanting to establish or transform theirbusiness as a fully-fledged, whollydemocratic entity – the kind that manyin the current movement have told usthey consider to be a true co‑operative.But we argue that these interests willalso be served by implementing apolicy agenda that also seeks a moregentle transition across the wholeeconomy towards greater democracyand participation in firms – not justco‑operatives – of all shapes and sizes.These are not mutually exclusive, butmutually reinforcing strategies.1. worker and freelance co‑operatives,with a controlling majority in thehands of the co‑operatives workers;2. consumer co‑operatives, wheremembership is based on thecustomers of the co‑operative;3. producer and enterpriseco‑operatives, such as in farming,where independent producers –usually small and micro businesses– come together as members to forma co‑operative, reducing their sharedfixed costs, participating in R&D,investing in infrastructure, capturingmore value-added in supply chains,and improving negotiating positionswith other companies;4. community co‑operatives, wheremembers are typically a group ofpeople with a defined commoninterest;5. and multi-stakeholder co‑operatives,where members typically representmore than one co‑operative group,such as workers, consumers, serviceusers or producers.While there are a variety of legal forms10

NEW ECONOMICS FOUNDATIONCO-OPERATIVES UNLEASHEDDOUBLING THE SIZE OF THEUK’S CO-OPERATIVE SECTOR3. CO‑OPERATIVESAS SYMPTOMS ANDAGENTS OF SYSTEMCHANGEThe co‑operative model – with itsdiffering ownership and governancemodel generating different outcomes– should be ubiquitous in an economythat is successful at democratisingownership and sustaining purposefulenterprise at scale. A growing co‑opsector would be one of many factorsthat could catalyse systemic change.But a flourishing sector will alsobe a symptom of a different typeof economy emerging, one wherethriving businesses are organised sothey address deep democratic deficitsgenerated by current patterns ofownership, and operate with values ofparticipation and community control,while placing a primacy on social andecological goals.Overcoming our deep,structural economicchallenges will requiresystemic solutions,because our pooroutcomes are rootedin how we currentlyorganise the economyand its institutions.If more people are tobenefit from economicproduction, theneconomic power andcontrol must rest moreequally, requiringmeasures to redistributeownership and control insociety and, ultimately,capital.Co‑operative flourishing in a moredemocratic, equitable, sustainableeconomy would advance whatRaymond Williams called ‘the longrevolution’ – the difficult and ongoingstruggle to build a society definedby democratic, open and purposefulrelationships, where hierarchies ofpower and illegitimate authority arereplaced with values of co‑operation,dignity and solidarity in an equitable,democratic and sustainable economy.Scaling democratic forms of ownershipthrough co‑operative expansion iscritical to that endeavour.11

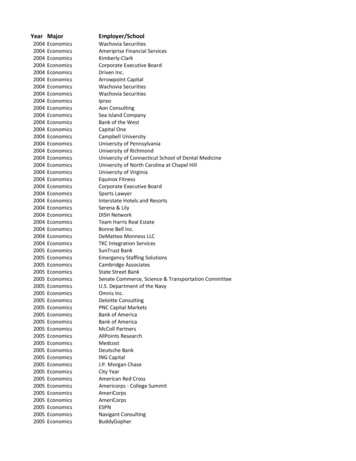

NEW ECONOMICS FOUNDATIONCO-OPERATIVES UNLEASHEDDOUBLING THE SIZE OF THEUK’S CO-OPERATIVE SECTOR4. THE CO‑OPERATIVEADVANTAGEThe geographic range of evidence isstriking. The productivity bonus ofco‑operatives has been confirmed inthe USA (Kruse, Freeman and Blasi2010; Pencavel and Craig 1994), France(Fakhfakh et al 2012), Spain (BayoMoriones, Galilea-Salvatierra and DeCerio 2003), Italy (Maietta and Sena2008) and Germany (Cable and FitzRoy1980), among others.The co‑operativeadvantage derivedfrom its organisationalform is considerable.Wide-ranging evidencesuggests that productivityin co‑ops is at leastas high if not higherthan ‘conventional’firms, primarily due toimproved motivationthrough a sense ofcollective ownershipand profit-sharing, andmore effective internalcoordination due tohigher levels of trustand the better use ofemployee know-how.Studies in the UK, meanwhile, havefound that co‑operatives, mutuals andemployee-owned enterprises with 75employees or fewer are outperformingconventional businesses, creatinghigher profits (both gross and peremployee) than non-employee ownedbusinesses (Welsh Co‑operative andMutuals Commission 2016). They arealso more resilient. More than 90% ofco‑operatives survive their first threeyears of operation compared with 65%of conventional businesses (ibid). Theevidence suggests that the co‑operativemodel not only offers all of thesystemic benefits of widening anddeepening the ownership and controlof free enterprise, but is also durableand highly economically viable.There is also evidence that evenrelatively diluted forms of employeeownership brings business benefits.Publicly listed companies quotedon the London Stock Exchange orAIM that have 3% or more of theirequity capital under employee controloutperform the wider FTSE all share.3Crucially, the co‑operative modelgenerates genuine social, economicand political benefits for its members,particularly compared to conventionalbusinesses. Co‑operatives have beenfound to have far lower levels of staffturnover compared with the average,lower pay inequality within the firm,and lower absenteeism rates (Mayo ed.2015). Workers in co‑operatives reportmuch higher levels of job satisfactionand economic well-being than those inprivately owned firms, as well as higher12

NEW ECONOMICS FOUNDATIONCO-OPERATIVES UNLEASHEDDOUBLING THE SIZE OF THEUK’S CO-OPERATIVE SECTORrates of engagement and productivity(Mayo ed. 2015; Freeman et al 2010).co‑operative federation, where smallto medium sized co‑operatives sharefunctions under an umbrella structure.Strikingly, in an era of unaccountablecorporate power and the facilitationby footloose capital of grand-scaletax avoidance, the five largestco‑operatives paid 50% more corporatetax than Amazon, Facebook, Apple,eBay and Starbucks combined(Co‑operatives UK 2016). And in anoften extractive global economic systemco‑operatives can localise finance. One2011 study found that employees ofJohn Lewis spent between 20% and25% of their partnership bonus (18%of annual salary in that year) within thesame local authority area as the shop inwhich they worked (NEFC 2011).This is not to say co‑operatives donot contain trade-offs. Co‑operativesare not suited to all industries orbusinesses. In particular, sectorsinvolving high capital intensity aresometimes less suitable, due to thehigher cost and risks that memberswould bear. In these cases, othermodels of democratic governance

recommendations into five interlocking steps: 1. A new legal framework for co‑operatives. 2. Finance that serves the co‑operative agenda. 3. Deepening co‑operative capabilities through a Co‑operative Development Agency. 4. Transforming business ownership. 5. Accelerating community wealth building initiatives. We firmly recommend that .