Transcription

The Magazine of the Arnold ArboretumVOLUM E6 4 N UM BE R1

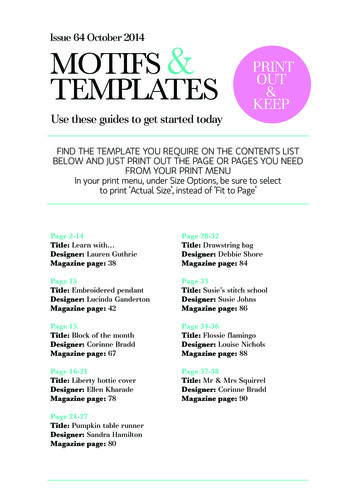

Volume 64 Number 1 2005Arnoldia (ISSN 004–2633; USPS 866–100) ispublished quarterly by the Arnold Arboretum ofHarvard University. Periodicals postage paid at Boston,Massachusetts.Subscriptions are 20.00 per calendar year domestic, 25.00 foreign, payable in advance. Single copies ofmost issues are 5.00; the exceptions are 58/4–59/1(Metasequoia After Fifty Years) and 54/4 (A Sourcebook of Cultivar Names), which are 10.00. Remittances may be made in U.S. dollars, by check drawnon a U.S. bank; by international money order; orby Visa or Mastercard. Send orders, remittances,change-of-address notices, and other subscriptionrelated communications to Circulation Manager,Arnoldia, Arnold Arboretum, 125 Arborway,Jamaica Plain, Massachusetts 02130–3500.Telephone 617.524.1718; facsimile 617.524.1418;e-mail arnoldia@arnarb.harvard.edu.Postmaster: Send address changes toArnoldia Circulation ManagerThe Arnold Arboretum125 ArborwayJamaica Plain, MA 02130–3500Karen Madsen, EditorMary Jane Kaplan, CopyeditorLois Brown, Editorial AssistantAndy Winther, DesignerEditorial CommitteePhyllis AndersenRobert E. CookPeter Del TrediciJianhua LiRichard SchulhofKim E. TrippCopyright 2005. The President and Fellows ofHarvard CollegePage2 Benjamin Bussey, Woodland Hill, and theCreation of the Arnold ArboretumMary Jane Wilson10The Founding of the Tree Museum inBussey ParkMrs. Edward Gilchrist Low12A Century of Breeding Bird Data—ChangesOver Time at the Arnold ArboretumRobert G. Mayer16The (un)Natural and Cultural History ofKorean Goldenrain TreeMichael S. Dosmann, Thomas H. Whitlow,& Kang Ho-Duck31Che: Chewy Dollops of Maroon SweetnessLee ReichOutside covers: Seat of Benjamin Bussey, Esq., at JamaicaPlain. Oil on canvas by William Cobb, 1839. This landscapeincludes the areas of the Arnold Arboretum that have cometo be known as Bussey Hill, Hemlock Hill, and the SouthStreet Tract. South Street is plainly visible, and it is easy tosee where Sawmill Brook—now Bussey Brook—crosses it.The Bussey mansion appears in the middle ground. Busseyhad begun buying up farmsteads in 1805 and continued todo so over the next thirty years. Some of the hedgerowsthat delineated the separate parcels appear in the painting.On the south slope of the hill, a lilac hedge, still extanttoday, formed one of these boundaries. This view of theArboretum from Walk Hill, near the Forest Hills transitstation, remains virtually unchanged today. From theArchives of the Arnold Arboretum, Harvard University.Inside front cover: Clockwise from top left, gray catbirdfledgling in a red osier dogwood near Faxon Pond; Baltimore oriole and nest in a cottonwood tree on Peters Hill;orchard oriole fledgling and nest, which is tethered to acrabapple on Peters Hill; young eastern kingbirds; greatcrested flycatcher in nest on Peters Hill.Inside back cover: Clockwise from top left, Baltimoreoriole in the nest in a red maple near Faxon Pond; youngeastern kingbird in a catalpa at the bottom of Bussey HillRoad; eastern kingbird nesting in a Kentucky coffeetreenear the ponds on Meadow Road; great horned owl perchedin a favored species—white pine—on Bussey Hill not farfrom the South Street gate; female boblink bearing food,resting on a hawthorn on Peters Hill.

Benjamin Bussey, Woodland Hill, and the Creationof the Arnold ArboretumMary Jane WilsonThe Arnold Arboretum was officially established in March 1872, when an indenture was signed by which trustees of a bequest of James Arnold agreed to turnthe fund over to Harvard College, provided the college would use it to develop anarboretum on land bequeathed earlier by Benjamin Bussey . . . An intense regardfor the land and for agricultural endeavor led Bussey to leave a large portion of hisfortune and all of his property in West Roxbury to Harvard College for the creationof an institution for instruction in farming, horticulture, botany, and related fields.—Ida Hay, Science in the Pleasure GroundThe following is adapted from the first full-length life of Bussey, soon to bepublished in its entirety.Ifirst met Benjamin Bussey when I openedan old family box labeled “ImportantPapers—Save.” Inside I found more than twohundred documents, primarily letters writtenin the early 1800s, addressed to a BenjaminBussey of Boston. It appeared that Bussey wasa man of importance in Federalist New England and that here was a story to be told. Myresearch confirmed that, indeed, Bussey was anoutstanding New Englander. The letters foundin that box have allowed me to piece togetherBenjamin Bussey’s life and encouraged the telling of his story. May history better rememberand recognize this extraordinary man who bettered the world in which he lived and whoselegacy remains today in a most special way,enhancing the lives of untold others, throughthe Arnold Arboretum.Benjamin Bussey (1757–1842) played an important role in the growth of commerce, manufacturing, and agriculture in New England. After achildhood of frugal living and hard work and asoldier’s travails in the American Revolution,he became a merchant, eventually amassing agreat fortune from European trade. He was alsoon the cutting edge of New England’s manufacturing industry, with woolen mills in Dedham,Massachusetts, that introduced the water-drivenBroad Power Loom to America. Throughout hislife he was a benefactor to many individuals aswell as to religious and civic organizations.As a farmer Bussey acquired vast tracts ofland from Boston, Massachusetts, to Bangor,Maine. At his country estate, Woodland Hill,he demonstrated his support for the new movement called “scientific farming.” His sponsorship of agricultural education, “remarkable inits foresight,”1 led to his bequest to HarvardCollege of Woodland Hill for a school of agriculture and horticulture. Harvard honored hisbequest in 1869 with the creation of the BusseyInstitution.The years have obscured his name. His millsin Dedham are gone, his properties in Mainein great part absorbed by the city of Bangor.Only traces of his life remain in the landscape:a street bearing the Bussey name in Dedhamand a hilltop and a brook named for him at theArnold Arboretum.Bussey had accumulated a great fortune by theearly 1800s. Around the same time, a combination of embargos, falling markets, and failing enterprises made the shipping business

less attractive, and he retiredfrom the merchant life. FiveSummer Street in Boston hadbeen his home since 1798. Theproperty included a mansionwith grounds and gardens anda carriage house for the family’shorses and vehicles. In 1806 hepurchased the farm of EleazerWeld, located in what was thenknown as West Roxbury, nowthe Jamaica Plain/Forest Hillssection of Boston, an area popular for country seats and summerrelaxation. Several of Bussey’sfriends had already establishedcountry estates. Joseph Barrellbuilt Pleasant Hill in Charlestown in 1791; Theodore Lyman,The Vale in 1793 in Waltham;and John Codman renovatedthe Russell estate in Lincoln in1797. These gentlemen farmersused new experimental methods to develop their lands. In1792, twenty-one lawyers, doctors, politicians, and merchantschartered the MassachusettsSociety for Promoting Agriculture (MSPA). The Societyacquired and disbursed information on crop rotation, refores- In 1808 Bussey made arrangements with the famed portraitist Gilbert Stuart totation, and the use of cattle to paint the family’s portraits. Bussey’s own was the last to be finished. Reportingprovide natural fertilizer. Bussey on its progress after a visit to Stuart’s studio, daughter Eliza wrote to hermother, who was with Benjamin in Bangor, “It is the very image of himself andjoined the Society in 1803.the pleasure I have in viewing it lessens the pain of our separation for I feel asAt this point in his life Bussey tho’ in his presence when I look at the portrait.”was virtually free to devote histime to managing his investments and his realland Hill would eventually grow to encompassestate. His son and daughter were grown andmore than three hundred acres.on their own: Benjamin III had graduated fromBussey immediately assumed managementHarvard and Eliza had married. Developingof the farm operations. Farmhands were hiredhis estate was now the major focus of his life,and a woman, Anna Sherman, was employed tobecoming both an experiment in developingwatch over the farmhouse needs. The land washis interest in scientific farming and an outletplowed and planted with new products such asfor the attachment to the land that had formedLiberian wheat, and outbuildings were erected,in his childhood and progressed to ornamenincluding a barn to house the livestock, cattle,tal gardening at the Summer Street residence.swine, and the newly introduced merino sheep.The spacious meadows, hills, and brooks, andHe also targeted reforestation for an importantthe excellence and variety of the Jamaica Plainrole in his farming activities. Except for onelandscape spoke to his agrarian nature. Woodstand of trees (later known as Hemlock Hill)COURTESY OF THE HARVARD UNIVERSITY PORTRAIT COLLECTION, HARVARD UNIVERSITY ART MUSEUMS. BEQUEST OF BENJAMIN BUSSEY, 1894Benjamin Bussey 3

ARCHIVES OF THE ARNOLD ARBORETUM4 Arnoldia 64/1Maps of land that now comprises the Arnold Arboretum. Benjamin Bussey greatly expanded his holdings between 1810(above) and 1840 (below).

COURTESY OF MRS. GEORGE SKINNER. ARCHIVES OF THE ARNOLD ARBORETUMBenjamin Bussey 5The mansion on Bussey Hill photographed in the 1930s.and a hillside oak that had escaped cutting, theland was treeless, having been cleared to supplythe city with firewood, to raise hay, and to grazeanimals. Shortly after the purchase of the farmBussey established the first of his woodlots,and by 1810 several areas of young woods weregrowing. He added numerous species of treesand shrubs to the estate, including Europeanlarch, catalpa, honey locust, and silver fir.Bussey chose to site his mansion on the southside of Weld Hill (now known as Bussey Hill),a commanding location that overlooked thegreat variety in his landscape: woods, brooks,fields, and meadows. While supervising thefarm operations, he watched his new homerise. If he was away, his daughter Eliza and herhusband Charles followed the progress of thebuilding. In July of 1816, when Bussey and hiswife Judith were enjoying a visit to SaratogaSprings, Eliza sent word that the new house wasbeginning to look finished, with windows setin the upper stories and the tops of the piazzasshingled.2 Charles reported a few days later onboth farm and house.[T]he hay of all sorts and the barley are nowunder cover . . . and the fields are seldom so verdant as the rain Sunday was a constant pour.Joe came very near losing his chickens, manyapparently dead after the flood. We brought theminto the house and by the application of flanneland by the children’s hands all but three wererestored to their anxious mothers. The work atthe new house proceeds with regularity. Abouttwo thirds of the plastering is Finished . . . that inthe attic and in the entry leading to it has manysmall cracks in it owing to its drying too fast,occasioned by its proximity to the roof . . . I havecut the dead limbs from the trees in the woodsnear the walk and the stone wall is finished tothe bottom of the summer house. I have alsotaken the dead wood from the honeysuckles. Wehave had some days past the company of MissEly and her sister from Hartford . . . have takentea with Aunt Lowder and have had Mr. andMrs. Parsons with us at dinner yesterday.3The finished mansion was a model of statelyneoclassical elegance. It was approached by agravel carriage road lined with gutters of granite sea pebbles and bordered with white pines

6 Arnoldia 64/1and horsechestnuts. At the top of the steepincline the road ended in a turnaround at themansion entrance, where granite steps led to afront porch floored with white marble tiles. Theinterior of the house reflected the popularity ofFrench decor at the time. The dining room wallpaper was of Paris views and monuments. Thedrawing room and parlor floors were coveredwith Brussels carpets. Damask draperies hungat the windows and throughout the house werecostly French furnishings, such as the setteeand set of chairs with needlework upholsterythat Bussey had acquired at the close of theFrench Revolution.Other accoutrements were added over theyears. In 1818 Bussey purchased a copy of theDeclaration of Independence for ten dollars, andin 1832, five copies of old masters painted byRembrandt Peale. Peale sent a note with themexpressing his gratitude “that five of his bestcopies of the masters would reside together inBussey’s hospitable mansion where they wouldbe appreciated properly.”4Plantings around the mansion included awide-spreading American elm, a weeping beech,and a black oak that in time would offer coolingshade. Nearby were cherry and mulberry trees.A few yards from the house, a crescent-shapedpond was fed by an underground reservoir thatpiped water down to the house. Stone steps anda cobblestone path wound up the hill behindthe house, bordered with lilacs and white pinesthat screened the distant working farm. Myrtle and lilies-of-the-valley covered the groundbeneath the trees. At the crest of the hill wasthe stone-based summerhouse where Busseyand his friends viewed the distant Great BlueHill and the town of Boston. Looking upwardobservers could see the heavens, and looking downward on a clear night, the stars werereflected in the crescent pool. The summerhouse later became an observatory.Friends and neighbors came to Woodland Hillto stroll through the ornamental plantings or toclimb the hill to the summerhouse, passing bythe sweet-smelling lilacs. Some came for tea,others for dinner. The mansion’s spacious roomsand many chairs (the west drawing room aloneheld forty-two) allowed the Busseys to entertainlarge groups. French china, silver pitchers, andcrystal goblets made for elegant serving. Muchof the food grew on Bussey’s land: the cherriescame from the orchards, the rhubarb from thegarden, and his livestock provided the popularroasted veal and calves-head soup.His neighbors included Enoch Bartlett ofBartlett pear fame; John Warren, a distinguishedphysician, known for his Roxbury russet apple;and Joseph Story, associate justice of the UnitedStates Supreme Court and a Harvard law professor. One frequent visitor, Dr. Thomas Gray,minister of the Third Parish in Roxbury, oftencame for dinner following the Sunday worshipservice. The short distance between the churchand Woodland Hill made it very convenient forGray to visit Bussey as well as for Bussey toattend the meetinghouse.Relatives and their families also spent manyhours at Woodland Hill. They came, mostlyfrom Boston, either by personal coach or by thepublic stage that had begun hourly service toRoxbury for twelve-and-a-half cents per passage. Eliza and Charles, living at 7 SummerStreet, Boston, brought their daughters Judith,Eleanor, Eliza, and Maria to play in the woodsand meadows.Bussey participated in local activities andhosted visiting dignitaries when they came totown. In 1824, when the Revolutionary War heroLafayette visited Roxbury, he joined the prominent politician H. A. S. Dearborn and GovernorWilliam Eustis in paying homage to this wellloved personage. Later, when President AndrewJackson came to Boston, he joined in anothergrand procession: Vice President Martin VanBuren rode in Bussey’s yellow coach drawn bya team of “six horses, richly caparisoned, andattended by liveried servants.”5In his seventies, Bussey placed the farmingoperations under the direction of his grandsonin-law, Francis Head. Comfortably settled intheir mansion, the Busseys enjoyed their Pealepaintings along with Gilbert Stuart’s portraitsof the family, the busts of John Adams, GeneralHenry Jackson, George Washington, and oneof Benjamin himself. Outdoor sculptures, Ital-

PHOTOGRAPH BY KENNETH R. ROBERTSON. ARCHIVES OF THE ARNOLD ARBORETUMBenjamin Bussey 7Benjamin Bussey planted this American elm (Ulmus americana) in front of his mansion, where it remained for a centuryand a half, until the mid 1970s, when it became one of the last of its kind in the Arnold Arboretum to succumb to Dutchelm disease.ian marble statues and vases, were set alongthe carriage turnaround and at the mansion’sentrance.The orchards produced acceptable apricotsand juicy plums and massard cherries thatBussey said were “for the birds because theytook their full share.” He added to the beautyof the rhododendrons, tulip trees, and lilacswith trails that wound through the woods, rudebridges that crossed Bussey Brook, and gold andsiver fish that swam in a willow-bordered pond.6He continued building a fence of giant ashlarsto encompass the entire estate. Some stoneswere two to three feet in length.By 1841, when Woodland Hill had reached apleasing maturity and had grown in size throughthe purchase of several additional farms, Busseyopened the gates to the public so that others

8 Arnoldia 64/1to establish “a course of instruction in practical agriculture, ornamental gardening, botany,and other branches of natural science . . . to becalled the Bussey Institution . . .”7 One-half ofthe income from his estates and property wasto be used to support the institution; the otherhalf was for the endowment of professorships orscholarships in the law and divinity schools.On the evening of January 13, 1842, BenjaminBussey Esq. died at his seat in Jamaica Plain,aged eighty-five years, a distinguished merchantof Boston, manufacturer of Dedham, benefactorof New England, and master of Woodland Hill.The deed for the Woodland Hill estate was conveyed to Harvard College by the trustees of theBussey estate on August 28, 1861. The BusseyInstitution’s School of Agriculture offered aARCHIVES OF THE ARNOLD ARBORETUMmight share in the beauty of the land. In Mayof that year, the final codicil of his will wassigned. After generously providing for his family, for three good friends, and for the BostonFemale Asylum, Bussey set forth a plan to benefit his fellow man through Harvard University.First, he directed a large portion of his estateto Harvard’s schools of law and theology, thetwo branches of education he considered mostimportant in advancing “the prosperity andhappiness of our common country.” Second, heprovided for a school of agriculture and horticulture. Following the deaths of any heirs andtheir families, Woodland Hill and his Bostonreal estate were to be conveyed to the Presidentand Fellows of Harvard College. He ordered thetrustees to retain the estate and with the monies and other properties he conveyed to themThis Gothic Revival building housed the Bussey Institution of Harvard University beginning in 1871, as directed by Bussey’swill. It was demolished after a destructive fire in 1971.

three-year program in farming, horticulture, agriculturalchemistry, economic zoology,and entomology. Students weretaken into the fields as anintroduction to practical farming and later to the Arboretumto study and collect plant specimens. The enrollment wassmall and decreased even moreafter land-grant colleges wereestablished. In 1908 the Busseywas reorganized as a researchinstitution with graduateinstruction only, and in 1936its activities were integratedwith the biology laboratoriesof Harvard and the Institutionitself was closed.In the 1870s, just after theBussey Institution’s inception,a portion of Woodland Hillwas incorporated by Harvardas part of a new venture, thecreation of an arboretum. Thenation’s first public arboretumwas named, not for Bussey butfor James Arnold, the New Bed- Remnants of Bussey’s outbuildings stood on Bussey Hill into the 1990s.ford merchant who donated the3Letters #46, Aug. 2, 1813, and #45, Aug. 13, 1816,funds for its development. Although Bussey’sBussey Collection, William L. Clements Library,connection to the land was obscured, theUniversity of Michigan, Ann Arbor.Arnold Arboretum offered in great measure4what he had desired—education and recreationPeale letter to Bussey, Nov. 3, 1832, Special Collections,Getty Center Institution for History of Art and theto untold numbers of citizens who daily walkHumanities, Los Angeles, California.the grounds and know its beauty. Benjamin5Bussey’s name lives on through the remainingAnnals and Reminiscences of Jamaica Plain, HarrietManning Whitcomb (Cambridge, MA: Riverside Press,professorships endowed by his will, through the1897), p. 54.learning passed on by the hundreds of students6of the Bussey Institution, and through the workIbid., p. 53.of Harvard’s Biological Laboratories.7Endnotes12“The Bussey Institution 1871–1929,” William MortonWheeler, in The Development of Harvard UniversitySince the Inauguration of President Eliot 1869–1929,ed. Samuel Eliot Morison (Cambridge: HarvardUniversity Press, 1930), p. 508.Bussey letter, Jul. 1816, Bussey Papers, DedhamHistorical Society.Wi l l o f B e n j a m i n B u s s e y, N o r f o l k C o u n t y,Massachusetts, Probate Court.Mary Jane Wilson is a Michigan native with a lifelonginterest in Michigan history. Her local and stateinvolvement includes the establishment of the Friends ofthe Capitol, Inc., and the Docent Guild of the MichiganHistorical Center. Her writings include “The Watch of theCapitol,” “Lansing, A Look to the Past,” and “The JuniorLeague of Lansing 1948–2003.”RÁCZ & DEBRECZY. ARCHIVES OF THE ARNOLD ARBORETUMBenjamin Bussey 9

THE FOUNDING OF THE TREE MUSEUM IN BUSSEY PARKJamaica Plain, Boston, MassCommonly Known as The Arnold ArboretumFrom an Address Delivered Before The Garden Club of Alameda CountyJune 11, 1922*By Mrs. Edward Gilchrist LowIn 1842 Benjamin Bussey died at his country estate, Woodland Hill, leaving mostof his property to Harvard College. His town house of Colonial type, with largegardens and stables in Summer Street, in the very centre of the city of Boston,was sold and the proceeds given to Harvard College. His widow was to continueto live at their country estate, Woodland Hill, Jamaica Plain. In 1849 the widowdied. Then a grand-daughter came into possession, having life tenure of the place.Eventually the greater part of the property was to be used for a School or College,where agriculture, botany and all scientific studies pertaining thereto should beestablished at Woodland Hill.This place had upon it a Mansion House, four cottages, stables, farm, barnsand outbuildings. There were 360 acres. In 1815 the place had been laid out by anarchitect, who evidently had great artistic taste. To approach the house from thestreet there was a fine avenue, fairly steep in ascent, bordered on either side bywhite pines and horse chestnuts, and on the west side of these were cherry andmulberry trees.The view from the Mansion House was very pleasing. To the south on the horizonline stretched the Blue Hills in Milton; in the immediate foreground was an oval ofgrass, decorated with marble statues and marble vases on which were carved masks;these came from Italy. Behind the house there were stone steps leading to a pathwinding round a hill for three quarters of a mile; it was bordered by trees—pines,beeches, wild cherry, Cercis canadensis, yellow laburnum, syringas and lilacs, andunder these were many flowering plants—lilies-of-the-valley, periwinkle, Liliumflavum and others.On the summit of the hill was an octagonal room called the Observatory, forthe extended view which spread out before one’s eyes—to the south the Blue Hills,the Hemlock Hill, the undulating country, pasture land, and to the east the StateHouse and Boston Harbor. Near the house were herbaceous borders interspersedwith shrubs—Magnolia, Umbrella tripetala, weeping cherry, a fine tulip tree, Liriodendron tulipifera, Narcissus poeticus, tulips, crocuses, Stars of Bethlehem, Cinnamon roses, etc.There were vegetable and fruit gardens and a cold glass house, where large plantsoleanders and other kinds, used to decorate the piazza, were wintered. The woods

ARCHIVES OF THE ARNOLD ARBORETUMBenjamin Bussey 11“Bussey’s Woods,” now known as Hemlock Hill, became a favorite site for recreation amongnineteenth-century Bostonians. Century Magazine published this view in 1892.were filled with wild flowers. There were picturesque stone bridges with roundarches, under which the brook babbled. This was fed by a living spring, whosefresh water ran through a fish pond, where gold fish swam about, then by a narrow marble trough, down a small bank; soon it leaped over rocks and stones until,checked in its swift course by the meadowland, it meandered slowly to join thelarger streams far away. There was a legend that the Indians in the early part ofthe eighteenth century came from afar to drink of this water, and it was alwayscalled The Indian Spring.There were pleasure grounds, fish ponds, orchards and the wondrous Hemlock Hill, designated by Sir Joseph Hooker of Kew Gardens, England, the finest inthe world.This is a description of Woodland Hill, now known in the archives at the CityHall, Boston, as Bussey Park, in 1842, at the time of Benjamin Bussey’s death.* The typescript in its entirety is in the Archives of the Arnold Arboretum. In 1901 Mrs. Low, agreat-granddaughter of Benjamin and Judith Bussey, established on her land in Groton, Massachusetts, “a college where instruction [was] given to women in Landscape Gardening, ElementaryArchitecture, Horticulture, Botany and allied subjects.”

ROBERT G. MAYERA Century of Breeding Bird Data—Changes OverTime at the Arnold ArboretumRobert G. MayerThe area that is now home to theArnold Arboretum attracted residentand migrating birds long before it wasofficially established in 1872. Birds beget birders, who in turn keep records of the species thatvisit and nest in a given location. By 1895, whenthe first known report of breeding populationswas compiled, the Arboretum encompassedall but fifteen of its current 265 acres. Whilethe landscape has not changed much over theintervening century, the living collections—now comprising over 4,500 woody plant taxa—have changed dramatically. Habitats within theArboretum’s boundaries include marshland,deciduous woods, coniferous areas, streams,and three manmade ponds surrounded bylawns, providing hospitable sites for manydiverse species of birds to raise their young.Lists drawn up by regular birders show thatwhile the number of nesting species at theArboretum has remained quite stable since1895, many changes have occurred in the lists’components. In this article I review thosechanges and speculate on their causes, as wellas on prospects for the future.The ListersIn 1895, Garden and Forest published a shortarticle in which Charles E. Faxon documented his bird sightings in the Arboretum over aperiod of several years. 1 According to thearticle, fifty species of birds were then nestingin the Arboretum. Sixteen years later, Faxonadded another five species to the list.2For the better part of his career at the ArnoldArboretum (1882–1918), Faxon was in charge ofthe library and herbarium, but it is as a botanical illustrator that he has been remembered.His publication list approaches two thousanddrawings. In a review of Charles S. Sargent’sSilva of North America, where many of theseYellow warbler sitting on nest in a mockorange on BusseyHill Road.drawings were published, naturalist John Muirdeclared him “the foremost botanical artistin America.”3Like that of many other scientists of his era,Faxon’s interest in natural science was broad;he was an enthusiastic birder as well as a botanist. Recognizing the importance of the Arboretum as a birding site, he set about to “put onrecord a statement of the present bird population of the place” so that future observers“[could] see how many of the present featheredtenants will remain.”4 Faxon is memorializedat the Arboretum by the name of one of thethree manmade ponds near the Bradley Collection of Rosaceous Plants.Miriam E. Dickey, for many years head of theeducation department of the Boston Children’sMuseum, led bird walks in the Arboretum

Breeding Bird DataThe LossesAs the list shows, the number ofbreeding species at the Arboretumhas decreased somewhat over thecentury. Twenty-seven speciesthat were recorded by previousobservers are most likely no longer nesting on the property. Twogame birds, bobwhite and ruffedgrouse, may have been extirpatedearly on by hunting or by habitatloss; another, ring-necked pheasant, was lastseen in 2000. The spotted sandpiper, black- andyellow-billed cuckoos, least flycatcher, barnswallow, and eastern bluebird have not nestedthere since the middle of the twentieth century,probably owing to the loss of suitable habitat andnesting sites and to a reduction in the overallpopulation of some of these species. Seven warbler species, as well as yellow-throated vireo andveery, have stopped nesting in the Arboretum.Some of these species have experienced significant population decreases throughout Massachusetts, while others may no longer be able tofind hospitable nesting sites in the increasinglyurban habitat. Ground nesting species, such asbobolink and field sparrow, have lost habitatsince the Arboretum staff began cutting the grassshorter at the beginning of the twentieth century; increasing numbers of dogs and walkers inthe meadows may also have discouraged nesting.That bobolinks have recently begun breedingagain on Peters Hill, discussed below, indicatesthat these trends can be reversed.The GainsOn the positive side, seven species that didnot appear on previous lists have been documented as confirmed or probable breeders atYellow warbler nestlings surrounded by mockorange.ROBERT G. MAYERnearly every Saturday for 35 years, from 1939through 1976. In 1976 she reported in an articlefor Bird Observer of New England 5 that she andher group of regular birders had seen nearly 150species of birds at the Arboretum, of which 45“[had] been seen on a nest with eggs or young.”Many of the observers were children from thesummer day camp that Dickey ran for n

on a U.S. bank; by international money order; or by Visa or Mastercard. Send orders, remittances, change-of-address notices, and other subscription- related communications to Circulation Manager, Arnoldia, Arnold Arboretum, 125 Arborway, Jamaica Plain, Massachusetts 02130-3500. Telephone 617.524.1718; facsimile 617.524.1418;