Transcription

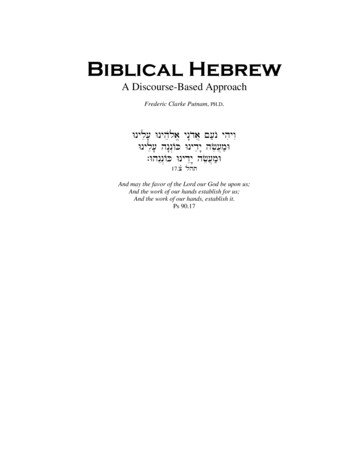

Biblical HebrewA Discourse-Based ApproachFrederic Clarke Putnam, PH.D.Wnyle[' WnyhelO a/ yn"dao ] [;nO yhiywIWnyle[' hn"nA K Wnydey" hfe[m] W; WhnEnA K WnydEy" hfe[]m;W17.c 'lhtAnd may the favor of the Lord our God be upon us;And the work of our hands establish for us;And the work of our hands, establish it.Ps 90.17

2006, 2009 Frederic Clarke PutnamAll rights reserved.2

PrefaceTof introductory grammars of Biblical Hebrew since c. 1990 begs the question: “Whyanother?” This grammar exists,first, because as my understanding of Hebrew1 became increasinglydiscourse- and genre-oriented, I needed a grammar from which to teach. When the supplementary handoutsovertook the “regular” textbook, I realized that it would be simpler just to fill in the gaps; you hold the result.Secondly, students who pursued postgraduate studies reported that they were better-prepared inHebrew than their classmates (and even, in some cases, were as well-prepared as their professors), andstrongly encouraged me to persevere. The positive response of other professionals, including linguists,translators, and professors, has likewise encouraged me to bring it to fruition.HE RISING TIDECharacteristics1. Frequency. As much as possible, those aspects of the language which are most frequent, common, or“usual” are studied before the less common. The verb is presented beginning with the two conjugations(imperfect and preterite) whose parallel morphology (common subject affixes) accounts for more thanforty percent of all verbal forms in Biblical Hebrew. Vocabulary is introduced in approximate order offrequency, allowing, of course, for the order of topics. The combined “supplementary” vocabulary lists(Appendix A) and those in the chapters introduce all words used fifty times or more in BIBLICALHEBREW (approximately 650 words in all). The verbal stems are the exception to this pattern offrequency; I find it more helpful pedagogically to link these by form and function rather than frequency.Furthermore, students find it helpful to interrupt the cascade of weak verbal roots with non-morphologicaltopics in order to allow students time to assimilate the characteristics of each type of root.There are a number of statistics scattered throughout the lessons, such as how often a particularconjugation, stem, or other form occurs. These statistics are not intended to imply or establish the relativesignificance of grammatical forms; they are included because students frequently ask how often they canexpect to see this or that phenomenon. Most of them are rounded off to the nearest whole number.2. Simplicity. First-year students need to learn enough grammar and syntax to get them into the text.Beginning to understand a language comes from extensive interaction with the language as it occurs, notfrom memorizing paradigms and vocabulary, necessary as that is. This text presents basic grammar asquickly as has proven practical, with the goal that students begin reading the text fairly early in their firstsemester of study. Noun formation is described very simply, and primarily in terms of recognition. Forexample, the guttural verbal roots are presented in one brief lesson, rather than a half-dozen lengthy ones.After completing this study, students should be able to develop their understanding of Hebrew grammarand syntax by reading the biblical text with the aid of standard reference works. By the end of their secondsemester/term of Hebrew, students should have read at least ten chapters directly from the Hebrew Bible,in addition to many partial and whole verses in the exercises.3. Continuity with previous language study. Semiticists traditionally arrange verbal charts (paradigms) fromthe third to the first persons (3rd-2nd-1st [e.g., she/he-you-I]), and pronominal paradigms in the oppositeorder (1st-2nd-3rd). This is both contrary to the experience of students who have studied other languages inhigh school or college (where all paradigms are arranged 1st-2nd-3rd person), and confusing to beginningstudents (who need to remember that the order varies according to the type of paradigm). This text uses theorder 1st-2nd-3rd for all paradigms. Students who pursue advanced studies in Hebrew or Semitics will needto orient themselves to the academic paradigms.4. A linguistic orientation. Explanations in this grammar assume that language in general is an aspect ofhuman behavior. Hebrew was a human language, a form of behavior that—like every other language—canbe more or less (and more rather than less) understood by other human beings. This reflects the furtherconviction that languages—and the utterances in which they are incarnate—thus exist and function within1Unless otherwise qualified, the terms “Biblical Hebrew” and “Hebrew” refer interchangeably to the language of the biblical text (MTas represented by BHS); “Classical Hebrew” refers to both biblical and epigraphic materials.3

larger societal patterns and systems; each part of any such system must, as much as possible, beunderstood in relation to the system of which it is a part, upon which it depends, and to which itcontributes.This text therefore aims at inculcating this understanding of language in general, and of BiblicalHebrew as an example of a particular stage of a specific language. Furthermore, since language is anaspect of human behavior, Biblical Hebrew is an example of the linguistic behavior of human beings—authors and speakers—in a particular time and place, and therefore must be read as an example of normalhuman communication, regardless of the speaker’s [author’s] understanding of his or her mission orpurpose in writing, and equally, without regard for the reader’s view of the Bible as human or divine (orhuman and divine) in origin. Biblical Hebrew is not some extraordinary language, chosen for its ability tocommunicate at or beyond certain levels of human understanding. It was merely one aspect of an everydayhuman language, and should be read as such.A specific appliction of this idea is that verbal conjugations are explained in terms of theirfunction in biblical genres. The string of preterites (wayyiqtol, “waw-conversive/consecutive plusimperfect”) in a biblical story outlines the backbone of the narrative, or the narrative chain; it is a formwith a discourse-level function that is related to the discourse-level functions of verbal conjugations, typesof clause, etc.At the same time, however, I have tried to avoid linguistic jargon and trivia, or at least to explainthem when they are introduced. The term “function” tends to replace the word “meaning,” and verbalconjugations are explained in terms of their contextual function (rather than “defined” by a list of possibletranslation values). There is a glossary of terms in Appendix C.5. Exercises. Most of the exercises are biblical texts taken from Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia (BHS). Inorder to allow teachers to assign texts that best suit the purposes and goals of their particular course andprogram, there are often more exercises than can be completed. [§5.10 explains the purpose and functionof the exercises.]6. Appendices. Appendices include supplementary vocabulary lists (above); an alphabetical list of propernouns (persons and places) that occur fifty times or more in the Hebrew Bible; pronominal and verbalparadigms, including a table of some easily confused verbal forms; a glossary of morphosyntactic terms; adescription of the qal passive; and an annotated bibliography.7. Schedule & Workload. This grammar was designed for two semesters (twenty-six weeks). The lessonsassume that an average student who follows a normal schedule of eight to twelve hours of study per weekin addition to time in class will achieve an average grade in the course.8. Pacing. The lessons introducing the “weak” verbal roots begin in Lesson 24. They are interspersed withlessons on reading biblical genres and the Masora because students found it helpful to have time to absorbone set of forms before encountering the next.Students and I have found it practical to work through Lessons 1-22 in one semester of fifteenweeks, meeting twice per week; in the second semester we alternate studying a lesson with translating anextended biblical text, for example, the story of Abraham (see “10. Additional Resources Online”, below).This means that they encounter verbal forms and vocabulary in the text before meeting them “formally” inthe grammar, which lets them connect the more abstract presentation with a biblical passage. We alsobegin reading at sight from the biblical text in the sixth or eighth week of the first semester, usually in anextra “reading session” of 30-45 minutes before or after the official class.9. References. References to HBI are to my Hebrew Bible Insert: A Student’s Guide to the Syntax of BiblicalHebrew (1996), a booklet covering nominal, adjectival, pronominal, verbal, and clausal syntax, the“major” masoretic accents, and complete verbal paradigms.10. Additional Resources Online. Reading notes on Abraham (Gn 12-25), Ruth (1-4), Jonah (1-4), and othermaterials may be downloaded without charge from www.fredputnam.org.4

Notes for TeachersMy courses entail many “discussions” or “conversations”—which appear ad hoc and ad lib to students, but arein fact carefully planned—that would make this work too long, tedious, and “chatty”. An example of this is theall-too-brief discussion of vocabulary (Lesson 2), which merely hints at a discussion of lexical and theoreticalsemantics and translation that resurfaces throughout their first year of study. In order to avoid this tediousness,and to protect other teachers from the need to disavow (at least some of) my idiosyncracies, I leave to theindividual teacher the task of filling in the gaps that are thereby necessarily created. In other words, becauseschools, teachers, and students are individual, what is effective in one context (a course, its teacher, and thecurriculum of which they are part) may not be in another, as any good teacher knows.AcknowledgementsI am both privileged and honored to be able to dedicate this work to my wife, Emilie, and our daughters, Lydiaand Abigail, who encourage and pray for me without ceasing. She is my crown; they are our delight.I am also thankful for the suggestions and corrections of many of my students, especially ChrisDrager, Abigail Redman, and Bob Van Arsdale; for those offered by Rick Houseknecht (Biblical TheologicalSeminary) and Michael Hildebrand (Toccoa Falls College), who have used this text in their own teaching; andfor the extensive editorial help of Julie Devall and Jordan Siverd (although not even they can catch all of myerrors). My goal in this, as in all things, is that people of the Book might grow in their ability to read it, andthus to delight in its beauty and truth.S.D.G.Frederic Clarke PutnamAscension MMVITrinity MMVIII5

ContentsPart I: Reading & Pronouncing Hebrew . 6Introduction . 71. Alphabet . 82. Vowels . 143. Syllables . 23Part II: Nominal GrammarGrammar andVerbal Grammar (I): The Qal . 314. The Noun (Article, Conjunction waw) . 325. The Verb: The Imperfect (Prefix Conjugation). 426. The Preterite . 557. Prepositions . 648. Commands & Prohibitions . 729. The Construct Chain . 7710. The Perfect (Suffix Conjugation) . 8411. Adjectives . 9112. The Participle (Verbal Adjective) . 9913. Pronominals (I): Independent . 10414. Pronominals (II): Suffixes . 11115. Stative Verbs (& Haya) . 12016. The Infinitives . 12917. Questions, Negation, Numerals . 137Part III: Verbal Grammar (II)(II) andReading Hebrew Narrative .18. Other Stems

Hebrew than their classmates (and even, in some cases, were as well-prepared as their professors), and strongly encouraged me to persevere. The positive response of other professionals, including linguists, translators, and professors, has likewise encouraged me to bring it to fruition. Characteristics 1. Frequency. As much as possible, those .