Transcription

CONGRESS OF THE UNITED STATESCONGRESSIONAL BUDGET OFFICEACBOPAPERA Series on ImmigrationImmigration Policyin the United StatesFEBRUARY 2006

2499

ACBOPA P ERImmigration Policyin the United StatesFebruary 2006The Congress of the United States O Congressional Budget Office

NotesNumbers in the text and tables may not add up to totals because of rounding.Unless otherwise indicated, the years referred to in this paper are fiscal years.

PrefaceImmigration has been a subject of legislation since the nation’s founding. In 1790, theCongress established a formal process enabling the foreign born to become U.S. citizens. Justover a century later, in response to increasing levels of immigration, the federal governmentassumed the task of reviewing and processing all immigrants seeking admission to the UnitedStates. Since then, numerous changes have been made to U.S. immigration policy.This paper, requested by the Chairman and Ranking Member of the Senate Finance Committee, is part of a series of reports by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) on immigration.The paper focuses on the evolution of U.S. immigration policy and presents statistics on thevarious categories of lawful admission and enforcement of the nation’s immigration laws. Inkeeping with CBO’s mandate to provide objective, nonpartisan analysis, the paper makes norecommendations.Douglas Hamilton is coordinating CBO’s series of reports on immigration. Selena Calderaand Paige Piper/Bach wrote the paper under the supervision of Patrice Gordon. AndrewGisselquist reviewed the manuscript for factual accuracy. David Brauer, Paul Cullinan, MarkGrabowicz, Theresa Gullo, Arlene Holen, Melissa Merrell, Noah Meyerson, Robert Murphy,Kathy Ruffing, Jennifer Smith, Ralph Smith, and Derek Trunkey provided helpful commentson early drafts of the paper, as did Eric Larson and Judith Droitcour of the GovernmentAccountability Office. (The assistance of external reviewers implies no responsibility for thefinal product, which rests solely with CBO.)Loretta Lettner edited the paper, and Christine Bogusz proofread it. Maureen Costantino prepared the paper for publication and designed the cover. Lenny Skutnik produced the printedcopies, and Annette Kalicki and Simone Thomas produced the electronic version for CBO’sWeb site (www.cbo.gov).Donald B. MarronActing DirectorFebruary 2006

ContentsSummaryviiThe Evolution of U.S. Immigration Policy1Categories of Lawful Admission to the United States2Permanent Admission4Temporary Admission10Enforcement of Immigration Laws11Unauthorized Aliens11Enforcement Procedures14Appendix: Becoming a U.S. Citizen17TablesS-1.Lawful Admissions and Issuances of Visas, 2000 to 20041.Permanent (Immigrant) Admissions, by Category ofNew Arrival, 1996 to 200442.Major Immigration Categories63.Numerical Ceilings and Admissions, by ImmigrationCategory, 20048Immigrant Admissions Under the Diversity Program,by Region, 1997 to 200410Number and Type of Nonimmigrant (Temporary) VisaIssuances, 1992 to 2003126.Enforcement Efforts, 1991 to 2004157.Administrative Reasons for Formal Removal, 1991 to 200416A-1.Requirements for Naturalization184.5.viii

VIIMMIGRATION POLICY IN THE UNITED STATESFigures1.2.Total Lawful Permanent Admissions, by AdmissionsCategory, 2004Percentage of Nonimmigrant Visas Issued, by VisaClassification, 2003511Box1.Definition of Terms3

SummaryImmigration policy in the United States reflects multiple goals. First, it serves to reunite families by admittingimmigrants who already have family members living inthe United States. Second, it seeks to admit workers withspecific skills and to fill positions in occupations deemedto be experiencing labor shortages. Third, it attempts toprovide a refuge for people who face the risk of political,racial, or religious persecution in their country of origin.Finally, it seeks to ensure diversity by providing admissionto people from countries with historically low rates of immigration to the United States. Several categories of permanent and temporary admission have been establishedto implement those wide-ranging goals.This Congressional Budget Office paper describes who iseligible for the various categories of legal admission andprovides the most recent data available about the numberof people admitted under each category. The paper alsodiscusses procedures currently used to enforce immigration laws and provides estimates of the number of peoplewho are in the United States illegally.Lawful EntryU.S. policy provides two distinct paths for the lawful admission of noncitizens, or “aliens”: permanent (immigrant) admission or temporary (nonimmigrant) admission. In the first category, aliens may be grantedpermanent admission by being accorded the status oflawful permanent residents (LPRs). Aliens admitted insuch a capacity are formally classified as “immigrants”and receive a permanent resident card, commonly referred to as a green card. Lawful permanent residents areeligible to work in the United States and may later applyfor U.S. citizenship.In 2004, the United States granted permanent admission,or LPR status, to about 946,000 noncitizens (see Summary Table 1). That figure is not a measure of first-timeentries into the United States, however. The U.S. Citizen-ship and Immigration Services—a bureau of the Department of Homeland Security—counts both entries of newimmigrants and adjustments to lawful permanent resident status (for those aliens already in the United States)as “admissions.” In 2004, roughly 584,000 adjustmentsto LPR status were granted, and about 362,000 new immigrants entered the country.The second path is admission on a temporary basis. Temporary admission encompasses a large and diverse groupof people who are granted entry to the United States fora specific purpose for a limited period of time. Reasonsfor such admissions include tourism, diplomatic missions, study, and temporary work. Under U.S. law,citizens of foreign countries admitted temporarily areclassified as “nonimmigrants.” (For definitions of termsused in this paper, see Box 1 on page 3.) Certain nonimmigrants may be permitted to work in the UnitedStates for a limited time depending on the type of visathey receive. However, they are not eligible for citizenshipthrough naturalization; nonimmigrants wishing to remain in the United States on a permanent basis mustapply for permanent admission.In 2004, the State Department issued about 5 million visas authorizing temporary admission to the United States,according to preliminary data. In addition, under theVisa Waiver Program, 15.8 million people were admittedthat year on a temporary basis. Under that program, eligible people may enter the United States without a visa forbusiness or pleasure visits of 90 days or less.The numbers presented in this paper indicate the flow ofnoncitizens into the United States but not their departure. Such information is not recorded. Official estimatesare available only on the departures of lawful permanentresidents. The Bureau of the Census has estimated that anaverage of 217,000 LPRs emigrated from the UnitedStates each year between 1990 and 2000.

VIIIIMMIGRATION POLICY IN THE UNITED STATESSummary Table 1.Lawful Admissions and Issuances of Visas, 2000 to 2004(Thousands)20002001200220032004Permanent (Immigrant) AdmissionsAdmissions of Lawful Permanent ResidentsaUnrestrictedImmediate Relatives of U.S. CitizensGenerally restrictedFamily-sponsored preference admissionsEmployment-sponsored preference admissionsRefugees and asylum-seekersbDiversity ,0641,064706946Temporary (Nonimmigrant) Admissions and IssuancescVisa IssuancesAdmissions Under the Visa Waiver Program (Includesmultiple entries) 015,762Source: Congressional Budget Office based on Department of Justice, Immigration and Naturalization Service, 2001 Statistical Yearbookof the Immigration and Naturalization Service (February 2003); Department of Homeland Security, Office of Immigration Statistics,2003 Yearbook of Immigration Statistics (September 2004) and 2004 Yearbook of Immigration Statistics (January 2006); andDepartment of State, Bureau of Consular Affairs, Report of the Visa Office 2003, available at http://travel.state.gov/visa/about/report/report 2750.html.a. This category includes both those aliens who entered the United States as lawful permanent residents (LPRs) and those already present inthe country who adjusted to LPR status in the year designated.b. Refugees and asylum-seekers are people who are unable or unwilling to return to their home country because of the risk of persecution orbecause of a well-founded fear of persecution. Refugees apply for admission from outside of the United States; asylum-seekers requestlegal admission from within the United States or at a U.S. port of entry.c. Because certain visas allow nonimmigrants to enter the United States within a window of a few years, the year of issuance might notreflect an alien's actual year of entry. Furthermore, Canadians who travel to the United States on business or as tourists on a short-termbasis generally do not need a visa, nor do eligible citizens from countries participating in the Visa Waiver Program.d. According to preliminary data from the Department of State.e. The Visa Waiver Program allows eligible citizens of 27 participating countries to enter the United States without a visa for visits of 90 daysor less that are related to business or tourism. The participating countries are Andorra, Australia, Austria, Belgium, Brunei, Denmark,Finland, France, Germany, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, Monaco, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway,Portugal, San Marino, Singapore, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom. In recording nonimmigrant admissions,multiple entries by the same individual are not distinguished from first-time entries; therefore, the figures provided do not accurately represent the yearly flow of new nonimmigrants to the United States under this program.Unlawful EntryIn addition to facilitating the lawful admission of bothimmigrants and nonimmigrants, U.S. policy addressesthe issue of unauthorized aliens in the United States. According to the Census Bureau and the former Immigration and Naturalization Service, about 7 million unauthorized aliens were in the United States in 2000. Otherresearchers have estimated that number at roughly10 million in early 2004. Although such estimates conveythe population of unauthorized aliens living in theUnited States in a given year, the other statistics presentedin this paper represent annual inflows of people into theUnited States, unless otherwise indicated.Aliens found to be in violation of U.S. immigration lawsmay be removed from the country through a formal pro-

SUMMARYcess (which can include penalties such as fines, imprisonment, or prohibition against future entry) or may be offered the chance to depart voluntarily (which does notpreclude future entry). In 2004, about 203,000 peoplewere formally removed, and about 1 million others de-parted voluntarily (some people may have done so morethan once). Of the 203,000 formal removals, 42,000 unauthorized aliens were subject to expedited removals, aprocess designed to speed up the removal of aliens seekingto enter the country illegally.IX

Immigration Policy in the United StatesThe Evolution of U.S. ImmigrationPolicyImmigration has been a subject of legislation for U.S.policymakers since the nation’s founding. In 1790, theCongress established a process enabling people bornabroad to become U.S. citizens. The first federal law limiting immigration qualitatively was enacted in 1875, prohibiting the admission of criminals and prostitutes. Thefollowing year, in addressing efforts by the states to control immigration, the Supreme Court declared that theregulation of immigration was the exclusive responsibilityof the federal government. As the number of immigrantsrose, the Congress established the Immigration Service in1891, and the federal government assumed responsibilityfor processing all immigrants seeking admission to theUnited States.During World War I, immigration levels were relativelylow. However, when mass immigration resumed after thewar, quantitative restrictions were introduced. The Congress established a new immigration policy: a nationalorigins quota system, enacted as part of the Quota Law in1921 and revised in 1924. Immigration was restricted byassigning each nationality a quota based on its representation in past U.S. census figures. The Department of Statedistributed a limited number of visas each year throughU.S. embassies abroad, and the Immigration Service admitted immigrants who arrived with a valid visa. Citizensof other countries could move permanently to the UnitedStates by applying for an immigrant visa. Foreign citizenstraveling to the United States for a limited time (for instance, foreign exchange students, business executives, ortourists) could apply for a nonimmigrant visa.Family reunification was a fundamental goal of theQuota Law of 1921 and the updated quota law of 1924.Those laws favored immediate relatives of U.S. citizensand other family members, either by exempting themfrom numerical restrictions or by granting them preference within the restrictions. Subsequent laws continuedto focus on family reunification as a major goal of immigration policy.The Immigration and Nationality Act Amendments of1965 abolished the national-origins quota system andestablished a categorical preference system. The new system provided preferences for relatives of U.S. citizens andlawful permanent residents and for immigrants with jobskills deemed useful to the United States. However, it didnot abolish numerical restrictions altogether. For countries in the Eastern Hemisphere (comprising Europe,Asia, Africa, and Australia), the amendments set percountry and total immigration caps, as well as a cap foreach of the preference categories. Although there was atotal cap established on immigration from the WesternHemisphere, neither the preference categories nor percountry limits were applied to immigrants from theWestern Hemisphere. Immediate relatives of U.S. citizens—spouses, children under 21, and parents of citizensover 21—were exempted from the caps.The policies established in the 1965 amendments are stilllargely in place, although they have been modified at various times. In 1976, the categorical preference system wasextended to applicants from the Western Hemisphere. In1978, the numerical restrictions for Eastern and WesternHemisphere immigration were combined into a singleannual worldwide ceiling of 290,000. The ImmigrationAct of 1990 added a category of admission based on diversity and increased the worldwide immigration ceilingto the current “flexible” cap of 675,000 per year. That capcan exceed 675,000 in any year when unused visas fromthe family-sponsored and employment-based categoriesare available from the previous year. For example, if only625,000 people were admitted in 2006, the cap wouldthen be raised to 725,000 for 2007.

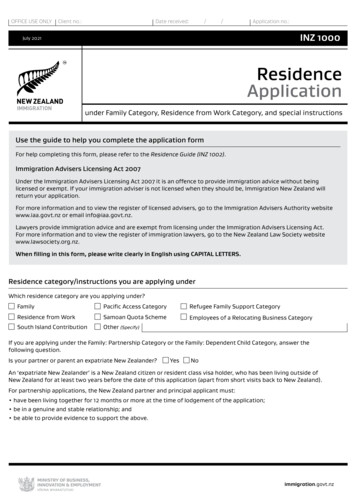

2IMMIGRATION POLICY IN THE UNITED STATESThe United States also has participated in the resettlement of specific groups of refugees since the close ofWorld War II. The Refugee Act of 1980 created a comprehensive refugee policy giving the President, in consultation with the Congress, the authority to determine thenumber of refugees that would be admitted on a yearlybasis. It brought U.S. policy in line with the 1967 Protocol to the 1951 United Nations Refugee Convention.The protocol, together with the 1969 Organization ofAfrican Unity Convention, expanded the number of people considered refugees. The Refugee Act adopted the internationally accepted definition of “refugee” containedin the U.N. Convention and Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees and applied the same definition to thoseseeking asylum.The Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986 addressed the issue of unauthorized immigration. It soughtto enhance enforcement and to create new pathways tolegal immigration. Sanctions were imposed on employerswho knowingly hired or recruited unauthorized aliens.The law also created two amnesty programs for unauthorized aliens and a new classification for seasonal agricultural workers. The Seasonal Agricultural Worker amnestyprogram allowed people who had worked for at least 90days in certain agricultural jobs to apply for permanentresident status. The Legally Authorized Workers amnestyprogram allowed current unauthorized aliens who hadlived in the United States since 1982 to legalize their status. Under the two amnesty programs, roughly 2.7 million people residing in the United States illegally becamelawful permanent residents.1In response to continuing concerns about unauthorizedimmigration, the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996 addressed border enforcement and the use of social services by immigrants. Itincreased the number of border patrol agents, introducednew border control measures, reduced government benefits available to immigrants, and established a pilot pro1. Nancy Rytina, “IRCA Legalization Effects: Lawful PermanentResidence and Naturalization through 2001” (paper presented atThe Effects of Immigrant Legalization Programs on the UnitedStates: Scientific Evidence on Immigrant Adaptation and Impacton U.S. Economy and Society, The Cloister, Mary WoodwardLasker Center, National Institutes of Health Main Campus,October 25, 2002).gram in which employers and social services agenciescould check by telephone or electronically to verify the eligibility of immigrants applying for work or social services benefits.2The Homeland Security Act of 2002 created the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and, in doing so, restructured the Immigration and Naturalization Service(INS), the agency formerly responsible for immigrationservices, border enforcement, and border inspections.Nearly all functions of the INS were transferred to DHS.Prior law had combined immigrant service and enforcement functions within the same agency; those functionsare now divided among different bureaus of DHS. Immigration and naturalization are the responsibility of theBureau of Citizenship and Immigration Services. Theborder enforcement functions of the INS are split between two bureaus: the Bureau of Customs and BorderProtection and the Bureau of Immigration and CustomsEnforcement.Categories of Lawful Admission to theUnited StatesCurrent immigration policy offers two distinct ways fornoncitizens to enter the United States lawfully: permanent (or immigrant) admission and temporary (or nonimmigrant) admission. People granted permanent admission are formally classified as lawful permanent residents(LPRs) and receive a green card. (The term “immigrant”is correctly applied only to that category of aliens. Formore definitions of terms used in this paper, see Box 1.)LPRs are eligible to work in the United States and eventually may apply for U.S. citizenship.3 Aliens eligible forpermanent admission include certain relatives of U.S. citizens and workers with specific job skills, among others.In 2004, the United States admitted about 946,000 people as lawful permanent residents.2. The employment verification pilot program is voluntary, and theGovernment Accountability Office has found weaknesses in it. SeeGovernment Accountability Office, Immigration Enforcement:Weaknesses Hinder Employment Verification and Worksite Enforcement Efforts, GAO-05-813 (August 2005).3. The naturalization process and requirements for citizenship aredescribed in the appendix.

IMMIGRATION POLICY IN THE UNITED STATESBox 1.Definition of TermsTerminology used throughout this paper is defined by the Department of Homeland Security’sBureau of Citizenship and Immigration Services:BAlien refers to any individual who is not acitizen of the United States.BImmigrant refers to an alien lawfully admitted to the United States for permanent residence; such people also may be referred to aslawful permanent residents.BNonimmigrant refers to an alien who seekstemporary entry to the United States for a specific purpose. Nonimmigrants include tourists, temporary workers, business executives,students, and diplomats.BRemoval is the expulsion of an alien from theUnited States. The expulsion may be based ongrounds of inadmissibility or deportability.BA U.S. visa allows the bearer to apply for entry to the United States under a certain classification. Examples of classifications includestudent (F), visitor (B), and temporary worker(H). A visa does not grant the bearer the rightto enter the United States. The Department ofState is responsible for visa adjudication atU.S. embassies and consulates outside of theUnited States. Immigration inspectors withthe Department of Homeland Security’s Bureau of Customs and Border Protection determine admission into the United States at aport of entry, as well as the duration and conditions of stay.The 946,000 new admissions reported for 2004 includemore than first-time entries into the United States. TheU.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS)counts as “admissions” both new entries of immigrantsand adjustments to LPR status for aliens already in theUnited States. In 2004, for example, roughly 584,000 ad-justments to LPR status were granted and about 362,000aliens entered the country for the first time (see Table 1).The second path to lawful admission is temporary admission, which is granted to foreign citizens who seek entryto the United States for a limited time and for a specificpurpose (such as tourism, diplomacy, temporary work, orstudy). Under U.S. law, aliens admitted on a temporarybasis are classified as “nonimmigrants.” Only nonimmigrants with a specific type of visa may be permittedto work in the United States. Nonimmigrants are not eligible for citizenship through naturalization; those wishing to remain in the United States permanently must apply for permanent admission. In 2004, about 5 millionpeople were granted visas for temporary admission.Annual issuances of temporary visas, however, are not ameasure of the number of nonimmigrants entering thecountry each year. Most temporary visas are valid for several years after they are issued. Thus, issuance and entrymay occur in different years, and visa holders may enterthe country multiple times. The USCIS does report annual admissions for nonimmigrants, but those numbersmeasure entries by nonimmigrants, not just first-time entries. For example, each entry by a foreign exchange student returning from his or her home country after schoolholidays is counted as an admission. Neither yearly temporary visa issuances nor yearly temporary admissions canbe directly compared with the measure of yearly permanent admissions.It is important to note that the numbers presentedthroughout this paper indicate flows of noncitizens intothe United States but not their departures. Informationon departures of noncitizens from the United States is notrecorded, and official estimates are available only on thedepartures of lawful permanent residents. An earlier paper by the Congressional Budget Office found that thebest estimates indicate that one-fourth to one-third of legal immigrants leave the United States, in most caseswithin several years of admission.4 The Census Bureau4. See Congressional Budget Office, A Description of the ImmigrantPopulation (November 2004); and Tammany J. Mulder, BetsyGuzmán, and Angela Brittingham, Evaluating Components ofInternational Migration: Foreign-Born Emigrants, Population Division Working Paper No. 62 (Department of Commerce, Bureauof the Census, April 2002), p. 6, available at www.census.gov/population/www/techpap.html.3

4IMMIGRATION POLICY IN THE UNITED STATESTable 1.Permanent (Immigrant) Admissions, by Category of New Arrival, 1996 to 20041996Number of New Admissions, by TypeFirst-time entry to the United StatesAdjustment of status to ,416583,921TotalPercentage of New Admissions, by TypeFirst-time entry to the United StatesAdjustment of status to ,807 1,064,318 1,063,732485239613664705,827946,14251493862Source: Congressional Budget Office based on Department of Homeland Security, Office of Immigration Statistics, 2004 Yearbook of Immigration Statistics (January 2006).Note: LPR lawful permanent resident.has estimated that between 1990 and 2000, an averageof 217,000 foreign-born people left the United Statesannually.5Permanent AdmissionUnder certain conditions, the United States may denyvisas or admission on either a temporary or a permanentbasis. For example, people may be denied admission onthe grounds of health, criminal history, security or terrorism concerns, the likelihood of their “becoming a publiccharge,” their seeking work in the United States withoutproper labor certification and qualifications, prior illegalentry or violations of immigration law, lack of properdocumentation, or previous removal from the country.Those grounds may be waived for certain admissioncategories.BTo reunite families by admitting immigrants who already have family members living in the United States;BTo admit workers in occupations with strong demandfor labor;BTo provide a refuge for people who face the risk of political, racial, or religious persecution in their homecountries; andBTo provide admission to people from a diverse set ofcountries.It is difficult to determine how many people might seekto enter the United States, on either a permanent or temporary basis. Various factors in addition to numerical limits affect those admissions. For example, backlogs in theprocessing of applications for visas for permanent legalresidency and for nonimmigrant visas may slow admissions for the year. Waiting periods may vary by countryand deter people who would otherwise seek lawful entryto the United States.5. Tammany J. Mulder and others, U.S. Census Bureau Measurementof Net International Migration to the United States: 1990 to 2000,Population Division Working Paper No. 51 (Department ofCommerce, Bureau of the Census, December 2001), available atwww.census.gov/population/www/techpap.html.The goals of current immigration policy are wideranging:Several categories of permanent admission have been established to implement those goals.Admissions of Immediate Relatives of U.S. Citizens. Inkeeping with the objective of family reunification, theimmediate relatives of U.S. citizens—spouses, parents ofcitizens ages 21 and older, and unmarried children under21—are admitted without numerical limitation. In 2004,about 406,000 immediate relatives of U.S. citizens wereadmitted, accounting for about 43 percent of all permanent admissions. Immediate relatives of citizens have generally accounted for the largest share of permanent immigrant admissions (see Figure 1).

IMMIGRATION POLICY IN THE UNITED STATESFigure 1.Total Lawful Permanent Admissions,by Admissions Category, 2004DiversityBased(5%)Other(5%)established ceilings—for instance, the 214,000 people admitted in 2004 compare with a total ceiling for all familybased categories of 226,000 visas—because of either lowdemand for visas or processing backlogs that sometimesaffect the number of admissions granted each year.Employment-Based Preference Admissions. Historically,U.S. immigration policy also has sought to bring inworkers with certain job skills. The country currently hasfive employment-based preference categories underwhich a person may be admitted:Refugees andAsylum-Seekers(8%)ImmediateRelatives ofU.S. BasedPreference(23%)BPriority workers with extraordinary ability in the arts,athletics, business, education, or science;6BProfessionals holding advanced degrees or individualsof exceptional ability;BWorkers in occupations deemed to be experiencingshortages;BSource: Congressional Budget Office based on Department ofHomeland Security, Office of Immigration Statistics,2004 Yearbook of Immigration Statistics (January 2006).Note: In 2004, the latest year for which data are available, therewere 946,142 permanent admissions.Family-Sponsored Preference Admissions. In addition totheir immediate relatives, U.S. citizens can sponsor otherrelatives for permanent admission under the familysponsored preference program, which is subject to numerical limits. Under that program, admission is governed by a system of ordered preferences (see Table 2). In2004, about 214,000 people—or 23 percent of all lawfulpermanent immigrants—were granted admission underthe family-sponsored preference program. Between thiscategory and the preceding (for immediate relatives ofU.S. citizens), family-based immigrants accounted for almost two-thirds of permanent admissions in 2004.The various preference categories under the familysponsored program (and under the employment-basedprogram described below) have different numerical limits(see Table 3). Unused visas in each category may bepassed to the next-lower preference category, and unusedvisas in the lowest preference category are passed on tothe first category. Actual admissions often fall short of theBReligious and other special workers;7 andPeople willing to invest at least 1 million in businesses located in the United States.A total of about 155,000 people were admitted in 2004under those employment-based preference categories, accounting for roughly 16 percent of permanent admissions. The majority of them—55 percent—were admitted as workers in occupations deemed to be experiencingshortages (see Table 3).For most immigrants to be admitted under theemployment-based preference program, an employermust first submit a lab

The Evolution of U.S. Immigration Policy Immigration has been a subject of legislation for U.S. policymakers since the nation's founding. In 1790, the Congress established a process enabling people born abroad to become U.S. citizens. The first federal law lim-iting immigration qualitatively was enacted in 1875, pro-