Transcription

Self-PracticeCecilia HarrisonThis edition of Iyengar Yoga News explores thetheme 'self-practice'. IYN is honoured to have twoexceptional international Iyengar yoga teacherscontribute to this theme. Dr Rajvi Mehta1 gives awonderful, illuminating personal insight into selfpractice from her earliest days as a student ofMr. Iyengar in Mumbai to her work now aspractitioner, teacher and researcher in yogatherapy in an interview. Mr Faeq Biria2 shares withus an article on self-practice and the codificationhe has made of yoga postures that prepare thebody for asana practice, discussing method andmeans through ancient texts and a life spentlearning from Guruji. Both the interview and thearticle bring to life something of the extraordinary texture of the Ramamani Iyengar MemorialYoga Institute, Pune, India.Iyengar Yoga News No. 24 - Spring 2014Iyengar Yoga TextsA totally transformative yoga practice sequence isgiven at the end of Yogacharya B.K.S. Iyengar'sbook Light on Life.Mr. Iyengar calls the sequence “Asanas forEmotional Stability”. He outlines asanas to calmthe mind and cool the brain, asanas to balance theintelligence of the head (the intellectual centre)and the intelligence of the heart (the emotionalcentre), asanas to stimulate the brain for positivethinking, an asana to bring quietness in the body,and an asana that allows the practitioner to experience inner silence.In Light on Yoga Mr Iyengar gives a short three daycourse “which whenever followed will benefit thebody and bring harmony to the mind” (p.466).Geeta Iyengar's Basic Guidelines for Teachers of Yogagives ten sequences that can go in rotation afterstudents learn the asanas from “PreliminaryCourse” – this variety of sequences of asanas shedescribes: “asanas work effectively on the body,4mind and breath in order to bring about therequired change” (p.57)Yoga changes us and transforms our energies. Thetexts of B.K.S. Iyengar and Geeta Iyengar are thecornerstone of Iyengar yoga practitioners selfpractice. Geeta Iyengar's superlative new bookYoga in Action – Intermediate Course 1 provides amethod for practice that, she writes, gives “a clueto the student on how to approach one's practiceand how one has to form practice sequences”(p. 111). The chapter on pranayama – the importance of pranayama – is for people who seek“calmness, quietness, silence and peace ofmind”(p.101).Daily Practice – Why is it important?The Dalai Lama writes the forward to B.K.S.Iyengar's Core of the Yoga Sutra's. The Dalai Lamaacknowledges the diversity of different traditions:“The most important thing is practice in daily lifethat is how we can gradually get to know the truevalue of whatever teaching we follow”.B.K.S. Iyengar writes “make your yoga sessions adaily practice” (p. 386 in Yoga: The Path to HolisticHealth)In How to Practice the Dalai Lama writes: “thecentral method for achieving a happier life is totrain your mind in a daily practice that weakensnegative attitudes and strengthens positive ones”(p.5)Through Iyengar yoga practice we seek to transform ourselves. This is a spiritual practice – ouraim is to increase awareness in order to bringfreedom through the exchange between body andmind learnt in asana and pranayama.1.Rajvi Mehta, senior teacher at Iyengar Yogashraya in Mumbai,India. Rajvi taught at the annual IY(UK) conference 2013.2. Faeq Biria co-directs the Iyengar Yoga Centre in Paris. Heteaches annual Iyengar Yoga intensives at Blacon, France.

Yoga-Kritya (Self-Practice)Faeq BiriaThe terms that we often use for practice areabhyasa and sadhana (which includes tapas).Sadhana conveys generally the idea of “means”and “aids” and especially the means and aids foremancipation. In the second chapter of yogasutras, Patanjali gives the three fold Kriya-yoga asthe method of sadhana and the astanga yoga asthe means to do sadhana.He talks about abhyasa in the first chapter. Thischapter is meant especially for the most vehement yogis. The precise description of NagojiBhatta of abhyasa as “the attempts made by yogiagain and again, to bring back the citta to the stateof stability within the stream of unmoving onepointedness, whenever it wanders outside of theobject of meditation” shows the important position of abhyasa in the hierarchy of yoga practice.For this reason, some of the traditional commentators of yoga sutras like Nagoji Bhatta himselfand Ramananda Yati believe that abhyasa and itsfollowing component vairagya cannot be practicedby someone who hasn’t yet attained the state ofCitta-suddhi (purification of the mind). VacasprtiMisra goes even further and demands the“purification of the entire personality” to becomeeligible for abhyasa.It must be based on this view that the yogis likeHariharananda Aranya, having most probably inmind the three works of Lord Patanjali (that werepeat in our daily invocation) consider the kriyayoga as the method to reach to a three-foldsamyama: Tapas as the control of the body Svadhyaya as the control of the speech Isvara-pranidhana as the control of the mindThe order of transformationThough I am asked to write about asana practice,yet I have to clear a first erroneous conceptionwhich consists of considering sadhana as only thepractice of asanas and the practice of asanas onlyon a physical plane.In our Guruji’s assessment of yoga sutras, sadhanameans the practice of all petals of yoga on physical, physiological, energetical, mental, intellectualand spiritual planes, with zeal, awareness anddevotion. The oral tradition of yoga has set anevolutive diagram for the natural transformationof a disciplined adept, and his evolution from mild(mrdu) state to a supremely intense (tivrasamvegin) level.Iyengar Yoga News No. 24 - Spring 2014Self-practice is the very foundation of yoga and allother paths of inner quest. I borrowed this termyoga-kritya from the great epic of India, TheMahabharata (XII. 294.6). It means the yogapractice.5

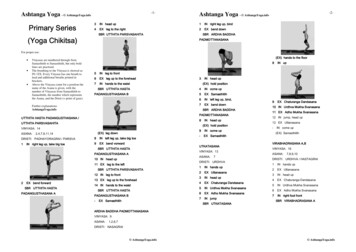

This means that a yogi of our Guruji’s attainmentcan engage fully his entire physical, mental andspiritual being in an asana and can get any asanafrom any layer, from the skin to the innermostcore of his being. This idea may look strange, evenshocking to the philosophers and they may evenobject against it: How can the atman or purusa,the immutable self, which cannot be grasped (thefamous quotation in Brhad-Aranyaka-Upanisad),which reveals itself only to itself, do an asana?The answer is by reaching to Guruji Iyengar’sstandard.Iyengar Yoga News No. 24 - Spring 2014Three major principles in the practiceof asanas1. The aim and goal of practice:We must define why we are practicing a sequenceor an asana and we must not forget it throughoutour practice. “Never lose the sight of the self”,says a famous yogic adage.We must also clearly define whether the aim ofpractice is: to learn? to consolidate? to study? to reach maturity in the asana?22. The personal mood:The approach to practice is very important.According to Bhagavad-Gita, the fruits of practicedepend upon the spirit with which we undertakethe practice. Some 40 years ago, I read an advicein Linga Maha-purana, that even after four decadesremains fresh in my mind and guides me in mydaily practice: “The aspirant must undertake thepractice always with a good mood”.3. Vinyasa or the proper sequencing:It is indispensable to respect a proper sequencingto reach the desired asana and to choose a rightmethod to realise through that desired asana thedesired effects or states inherent to it.Etymologically vinyasa means “arrangement”,“order”, “putting in”, “placing down” or “position(of the limbs)”. Most probably the term was usedin the ancient art of jewelry as the art of6arranging and positioning the gems, and reachedyogasastra through Mimamsa-darsana.Guruji Iyengar defines Vinyasa as “a sequence toreach the ultimate or final state of asana, wherethe mind and intelligence, along with energy(prana) and conscious awareness (prajna) are builtup within the system in different aspects ofhuman beings sequentially and gradually”1. Thereis a great adage attributed to a yogi of old times,Vamana Rishi: “O yogi, never attend the practicewithout proper sequencing”.Three stages in the practice of an asanaThe yogasanas must be performed with respect tothe three stages of practice of an asana. Indeedthe yogis have divided the practice of an asanainto three stages2, borrowing two terms fromSad-Linga3 for the first and the third stages:1. Upakrama3, the beginning, the introductionor: how to enter into the pose.Vacaspati Misra, Vijnana Bhiksu and Bhoja Raja, allbelieve that the word asana has as root “as” (tosit) and define it as asyate ’nena, that is “theprocedure and way through which one enters inthe pose”. Unfortunately most of Iyengar yogapractitioners feel only concerned by this stageand only on a purely physical level. Prashantjioften insists on the fact that upakrama mustcondition the body, the mind, the intelligence andthe awareness to go into the pose, and to reachthe purpose of it.22. Sthiti, maintaining or: how to stay in the pose.This is the stage where the very effects of theasana are created. The students of yoga who visitPune and observe our Guruji’s practice, areamazed to see the stability and the deepintrospective state with which the master stays ineach pose. We can almost consider this stage asasana-jaya or the conquest of the pose.3. Upasamhara3, the end, the conclusion, therecapitulation or, how to conclude the pose.

Iyengar Yoga News No. 24 - Spring 20147

How to prepare the body and its components for the practice of asanasOnce I have read in one of the Puranas (mostprobably in Visnu Maha-Purana) that in old timesthe guru, before initiating a disciple into a newasana, used to give him proper mantras whichprepared the specific parts of his body to get thepose without effort.Prashantji has studied deeply the effects ofvibrations of Sanskrit alphabet on the body andmind and I am sure that readers who have hadthe good luck of participating in his classes havebeen amazed realising the powerful effect of thesevibrations on their body, breath and mind.4Iyengar Yoga News No. 24 - Spring 2014In the early 1970s when I was travelling as astudent of yoga, I saw in a yoga community howthey fed the aspirants, from childhood, with aspecial diet (with a completely secret recipe) forabout twelve years. This, along with three sessionsof practice a day, created a full disposition in theirbodies to get the most complicated asanas with a8great ease (I saw the children in the backyard ofthe monastery having fun, balancing in Kandasanawith the heels under the throat!). I witnessed alsoa Kalaripayyattu5 master of Nair clan who throughdiet, full rest in a dark room and long sessions ofoil massage, created such a softness in the bodytissues of his disciples that he could adjust eventhe scoliotic spines, before re-muscling the bodyagain, curing deformity.How Guruji’s words ignited in me thereflection over the preparation of the bodyfor asanasTwo incidents particularly made me think offinding the way to prepare the body for enteringin a specific asana: During the years when Iyengaryoga was beginning to be spread in the world,many people used to practice with Light on Yoga.Sometimes they used to write to Guruji abouttheir injuries caused by practice or their failuresin getting some advanced asanas. It was amazingto see how quickly Guruji used to answer them: ifthe injury came while practicing a pose, it wasbecause anotherpose, whichwas on alower hierarchy in Lighton Yoga, hasnot been wellpracticed. Ifone did fail ingetting a newpose, it wasbecause thepreparatoryposes inprecedingweeks of theprogrammehave not beenwellmastered.The secondincidenthappened

He could open the body andmind of all of us within a fewminutes with a few very wellchosen points and then have usdoing the most difficult asanaswith ease, comfort andpleasure. I will never forget thathot evening of April 1980 whenhe walked in and asked us togo directly in an intensevariation of ViparitaDandasana. That day he showedus that he could also preparethe body for an asana, throughthe asana itself.6 Indeed, as toldme once by the late VandaScaravelli, “he did himself theposes for us, within us, makingus believing that we were doingGuruji’s method ofpreparing the body forasanasThis became the beginning of anew era ofreflection for.alertness of activity andme. Havingparticipatedpassivity in the body are increasedfor so manyor decreased, which helps to openyears in thethe horizon of the mindclasses taughtby Guruji,Geeta and Prashant I began tothem by ourselves”, breakingthink about the preparationsthis way our psychological andthey used to give in theirmental barriers. I learned toclasses and their methods ofponder over the pose that Ilinking. In October 1989, duringwas going to do or to teacha walk one very cold evening inand, inspired by Guruji’sMoscow, Guruji granted mesequencings, I started towith a few precious guidelinesprepare the body graduallyto think about the hierarchy ofthrough the other simple (andasanas and about the preparasometimes more difficult)7poses to get that requiredtions of the body. However, itpose.took me almost eight years ofpractice, teaching and observaGuruji calls this method thetion to reach to a satisfactorypratiloma vinyasa of samputanaclassification, approved bykriya (ascending sequence ofMaster.encasement action) and callsthe returning method asI had always understood andanuloma vinyasa. He explainsadmitted with humility thatvery beautifully: “This way ofnone of us could be Guruji!changing the body, vital energy,mind, senses of perception, andlightening the intelligence and“I”-consciousness (ego) iscalled pratiloma vinyasa,whereas returning fromcomplicated to simple asanaand pacifying the completesystem of the body andconsciousness is called anulomavinyasa. This way, the alertnessof activity and passivity in thebody are increased ordecreased, which helps to openthe horizon of the mind.”1Aum Sri Gurubhyo Namah 123456

Iyengar Yoga Texts A totally transformative yoga practice sequence is given at the end of Yogacharya B.K.S. Iyengar's book Light on Life. Mr. Iyengar calls the sequence “ Asanas for Emotional Stability”. He outlines asanas to calm the mind and cool the brain, asanas to balance the intelligence of the head (the intellectual centre) and the intelligence of the heart (the emotional centre .