Transcription

At the Intersection of Health, Health Care and PolicyCite this article as:Allison B. Rosen, Ana Aizcorbe, Alexander J. Ryu, Nicole Nestoriak, David M. Cutlerand Michael E. ChernewPolicy Makers Will Need A Way To Update Bundled Payments That Reflects HighlySkewed Spending Growth Of Various Care EpisodesHealth Affairs, 32, no.5 (2013):944-951doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1246The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, isavailable 44.full.htmlFor Reprints, Links & Permissions:http://healthaffairs.org/1340 reprints.phpE-mail Alerts : c.dtlTo Subscribe: ine.shtmlHealth Affairs is published monthly by Project HOPE at 7500 Old Georgetown Road, Suite 600,Bethesda, MD 20814-6133. Copyright 2013 by Project HOPE - The People-to-People HealthFoundation. As provided by United States copyright law (Title 17, U.S. Code), no part of HealthAffairs may be reproduced, displayed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic ormechanical, including photocopying or by information storage or retrieval systems, without priorwritten permission from the Publisher. All rights reserved.Not for commercial use or unauthorized distributionDownloaded from content.healthaffairs.org by Health Affairs on July 11, 2013at LIBRARY OF MEDICINE

Hospital Payment10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1246HEALTH AFFAIRS 32,NO. 5 (2013): 944–951 2013 Project HOPE—The People-to-People HealthFoundation, Inc.doi:Allison B. Rosen(Allison.Rosen@umassmed.edu) is an associate professorof quantitative healthsciences at the University ofMassachusetts MedicalSchool, in Worcester.Ana Aizcorbe is the chiefeconomist at the Bureau ofEconomic Analysis, inWashington, D.C.Alexander J. Ryu is a medicalstudent at Harvard MedicalSchool, in Boston.Nicole Nestoriak is a researcheconomist at the Bureau ofLabor Statistics, inWashington, D.C.David M. Cutler is the OttoEckstein Professor of AppliedEconomics at HarvardUniversity.Michael E. Chernew is aprofessor in the Departmentof Health Care Policy atHarvard Medical School.By Allison B. Rosen, Ana Aizcorbe, Alexander J. Ryu, Nicole Nestoriak, David M. Cutler, andMichael E. ChernewPolicy Makers Will Need A Way ToUpdate Bundled Payments ThatReflects Highly Skewed SpendingGrowth Of Various Care EpisodesABSTRACT Bundled payment entails paying a single price for all servicesdelivered as part of an episode of care for a specific condition. It is seenas a promising way to slow the growth of health care spending whilemaintaining or improving the quality of care. To implement bundledpayment, policy makers must set base payment rates for episodes of careand update the rates over time to reflect changes in the costs ofdelivering care and the components of care. Adopting the fee-for-serviceparadigm of adjusting payments with uniform update rates would be fairand accurate if costs increased at a uniform rate across episodes. But ouranalysis of 2003 and 2007 US commercial claims data showed spendinggrowth to be highly skewed across episodes: 10 percent of episodesaccounted for 82.5 percent of spending growth, and within-episodespending growth ranged from a decline of 75 percent to an increase of323 percent. Given that spending growth was much faster for someepisodes than for others, a situation known as skewness, policy makersshould not update episode payments using uniform update rates. Rather,they should explore ways to address variations in spending growth, suchas updating episode payments one by one, at least at the outset.Bundled payment for episodes ofcare has received significant attention as a means of slowing therapid growth of health care spending that has occurred under thefee-for-service system. Such payment systemspay a single price for all services delivered as partof an episode of care for a specific condition.Both public and private payers are experimenting with episode-based payment modelsas a way to curb spending growth and improvethe quality of care.1 At the federal level, this typeof reimbursement has been used for MedicareParts A and B services in selected demonstrations. For example, it is being used by theCenter for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation’s Bundled Payments for Care Improve944Health Affa irsM ay 20 1 33 2: 5ment initiative to test four innovative bundlingapproaches across a mix of hospital, hospitalphysician, and postacute care services.2At the state level, Arkansas Medicaid and private insurers partnered in 2011 to form theArkansas Health Care Payment ImprovementInitiative, which aims to move the state’s medicalspending to bundled payment.3 In the privatesector, Geisinger Health System offers a bundledpayment rate for coronary artery bypass surgerythat includes both pre- and postoperative care.1As bundled payment programs evolve, it is likelythat they will increasingly be used in conjunctionwith other payment models. For example, payersand providers could agree to a global budget foroverall spending and then to bundled paymentswithin that amount for discretely defined epi-Downloaded from content.healthaffairs.org by Health Affairs on July 11, 2013at LIBRARY OF MEDICINE

sodes, such as hip replacements.Despite burgeoning interest in bundled payment models, implementation has been challenging because of many persistent barriers.4One such barrier is how payment rates shouldbe set and later updated over time to reflectchanges in the costs of delivering care. The initialpayment rate may be set to provide a one-timereduction in spending. However, the success ofsuch systems in slowing the trajectory of spending growth—bending the cost curve—will greatlydepend on how the bundled payment rates areupdated over time. It will also depend on the extent to which spending growth reflects changesin spending per episode (which may be controlled by limiting growth in episode payments)versus changes in the number of episodes (whichmay not).Initially, bundled payments may be updatedusing the paradigm employed by Medicare,which bases updates on recent cost growth within each broad service category—for instance,physician services or hospital care. At present,Medicare reimbursement rates are based on a setof relative weights applied to all services within agiven service category and a conversion factor, orbase payment rate, to which these weights areapplied. It is the conversion factor that gets updated over time.Payments for acute care inpatient hospitalstays under Medicare Part A are a perfect example. Each inpatient hospital stay is categorizedinto a diagnosis-related group (DRG), and eachDRG in turn has a relative payment weight assigned to it that is based on the average resourcesused to treat Medicare patients in that group.Medicare applies these relative weights to thesingle conversion factor to obtain the paymentamounts for each DRG.For instance, the DRG weight for an admissionfor a kidney transplant is 3.0825. Payment in anygiven year, ignoring some adjustments that arenot specific to any DRG, is thus 3.0825 times theconversion factor, which was about 5,300 in2013. For an admission associated with anginapectoris, the DRG weight is 0.5207. So paymentis 0.5207 times the same conversion factor. Overtime, the conversion factor gets updated, but theDRG weights are generally kept the same unlessspecial adjustments are made. For example, therelative weight of a specific DRG might be increased to encourage the use of a less invasivebut more costly treatment if it improves patientoutcomes.If spending growth among services is heavilyskewed—that is, much more rapid for some thanfor others—applying uniform updates will createinequities in pricing. For example, if the cost ofadmission for kidney transplants rises fasterthan the cost of admission for angina pectoris,the updates will be inaccurate unless the Centersfor Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS)makes special adjustments. Although the relative weights can be changed, it is a cumbersomeand often criticized process.5 The uniformitymakes updating easier.The problem of pricing inequity may be evenmore serious with episodes than with DRGs,which include only inpatient payments, becausethe breadth of the bundle is greater, reflecting alarger number of services. As a result, spendinggrowth can reflect more factors, probably increasing the variation.The extent to which bundled payments couldbe uniformly and fairly updated using methodssimilar to those used by Medicare depends onthe skewness of spending growth. If spendinggrowth is skewed across episodes, a uniform update factor would not be ideal.To provide insight into these issues, we decomposed spending growth into the portion attributable to changes in episode volume versuschanges in episode spending, and we exploredin greater detail the clinical conditions that contribute the most and the least to per capita spending growth. We also examined the skewness ofspending growth across episodes of care in alarge, commercially insured population.Study Data And MethodsData We used data from the 2003 and 2007MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters Database from Truven Health Analytics(formerly Thomson Reuters and, before that,MedStat). The MarketScan data captured theclaims of about 17.5 million commercially insured people in 2003 and, because of an increasing number of employers submitting claims,more than 31 million in 2007. About half ofthe insurance claims for this period were submitted by very large employers; the other halfwere submitted by insurance plans. Insuranceplan data included claims from both large andsmall firms.For each of these years we selected peopleunder age sixty-five who had drug coverage, werein a commercial plan with valid plan type, andwere continuously enrolled for the full year (thisrequirement was to ensure that entire episodeswere captured). We excluded people enrolled incapitated plans because their utilization data arefrequently incomplete, which complicates episode formation and spending estimation. Thisprocess left 5.8 million and 11.1 million people inour samples for 2003 and 2007, respectively.We used three types of files for each year. First,the enrollment files contained information onMay 2 01332:5Downloaded from content.healthaffairs.org by Health Affairs on July 11, 2013at LIBRARY OF MEDICINEH ea lt h A f fai r s945

Hospital Paymentpatient demographics, enrollment periods, andtype of health insurance coverage. Second, theevent files contained inpatient, outpatient, andprescription drug claims, and they includeddates and types of services, diagnosis (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision,Clinical Modification, or ICD-9-CM) and procedure (Current Procedural Terminology, FourthEdition, or CPT-4) codes, types of providers, andcosts of services.Third, the episode files linked each event witha clearly defined episode of care and providedinformation on the type of episode, discussedbelow. These data included information on bothreimbursements and charges. However, all analyses used the actual amount received by theprovider, which included payments from boththe insurer and the patient.Methods We classified spending into episodes using Truven Health Analytics’ MedicalEpisode Grouper, which is widely available.6This commercial grouper employs a proprietaryalgorithm, based on clinical knowledge, whichreviews claims and either assigns them to one of569 possible episodes of care for different conditions or classifies them as “ungroupable.” Ungroupable claims were typically claims for prescription drugs or ancillary services such aslaboratory or radiologic tests for patients whodid not have a relevant episode for the service.Weomitted these claims from our analysis.We further classified the episodes into five different types using the labels that the grouperassigned to each episode: acute, three types ofchronic episodes (chronic maintenance, exacerbation of chronic condition, and chronic nonstratified), and well care.We combined the threechronic episode types into a single chroniccategory for reporting summary statistics andspending growth by disease, but we describethem separately when reporting spendinggrowth by episode acuity. The lone well care episode, “encounter for preventive health services,”was considered separately.For each episode, we computed average spending per episode in 2003 and 2007 and the totalcount of episodes per capita, adjusted for age andsex.7 We decomposed overall spending growthinto growth in the number of episodes, changesin the mix of episodes, and growth in spendingper episode, both at the disease level and foroverall spending. We then examined the distribution of spending growth by episode acuity,calculating the contribution to overall spendinggrowth for each type of episode.Finally, we examined the distribution ofspending growth across disease categories, andwe calculated the contribution of each disease tooverall spending growth and, importantly, the946Health A ffairsMay 2 01332:5heterogeneity in spending growth per episode.The formulas used for our decomposition areprovided in the online Appendix.8To address the possibility that findings wereunduly affected by outliers, we conducted a sensitivity analysis in which cost was top coded atthe ninety-ninth percentile within each episodetype. Analyses were conducted using two statistical software packages: SAS version 9.2 andStata version 11.Limitations Our study had some limitations.First, our data set, although large, is a convenience sample from select employers and insurers—and thus is not representative of the privatemarket. Our sample was restricted to peopleunder age sixty-five who were continuously enrolled in noncapitated plans with drug coverage.These exclusions were necessary to ensure complete claims data on all members of the sample.We excluded 20 percent of spending from ouranalyses because we could not group thoseamounts to a particular episode. Although thedistribution of spending growth across episodeswas determined using one commercial grouper,there are several other episode groupers in use ordevelopment. However, we would expect spending growth across episodes to be skewed regardless of which grouper is used.Another limitation related to our inability toassess the appropriateness of episode spendinggrowth or whether the appropriateness of spending growth per episode varied across episodes.Also, our use of fee-for-service spending growthas a basis for projecting episode trends assumesno behavioral changes on the part of providers inresponse to bundled payment incentives. Ourresults nonetheless illustrate the skewness inspending growth observed in the past; it remainsto be seen how new payment models would (orshould) affect that.Despite these limitations, this study is broadlyrelevant to payers and policy makers interestedin operationalizing bundled payment.Study ResultsDescriptive statistics for our sample are shown inExhibit 1. The age and sex distribution of oursamples remained relatively constant over time.Overall, the grouper allocated 78 percent ofspending into 558 types of episodes: 361 acute,196 chronic,9 and one well care. The grouper wasunable to allocate 23.7 percent and 21.1 percentof spending to episodes in 2003 and 2007, respectively. The final sample included total annual spending of 18.9 billion and 42.1 billionin 2003 and 2007, respectively, on inpatientservices, outpatient services, and prescriptiondrugs.Downloaded from content.healthaffairs.org by Health Affairs on July 11, 2013at LIBRARY OF MEDICINE

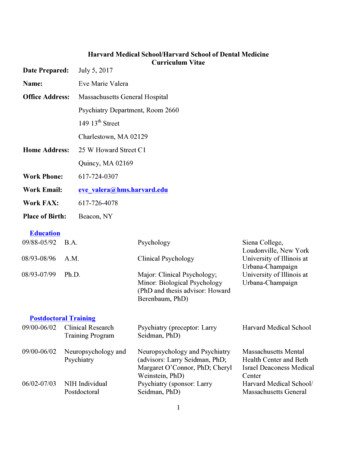

Between 2003 and 2007, spending per capitaincreased by 15 percent, from approximately 3,253 to 3,739, holding age and sex constant.This increase was lower than the national privatespending growth rate of 21 percent, which includes growth due to the aging of the population.10 Exhibit 2 displays the decomposition ofper capita spending growth into changes inspending per episode, episode mix, a shift fromlower-cost to higher-cost episodes or the reverse,and the number of episodes per beneficiary.The increase in spending per episode was thekey driver of spending growth, accounting for73 percent of the total. The number of episodesper person increased as well, from 10.39 to 10.94,accounting for a 36 percent increase in spendinggrowth. The episode mix was slightly tilted toless expensive episodes over time, although notgreatly.Spending growth was highly skewed, with10 percent of episodes accounting for 82.5 percent of total spending growth. Spending on the10 percent of episodes with the smallest contribution to cost growth actually decreased 12.9 percent between 2003 and 2007, contributing 16 percent to overall spending growth. Amongepisodes with at least 1,000 observations peryear, spending per episode rose 323 percent inthe fastest-growth episode and fell 75.5 percentin the slowest.Exhibit 3 displays the contribution to spending growth of the major episode types. Chronicepisodes accounted for 43.5 percent of baselinespending and 40.6 percent of spending growth.Acute episodes accounted for 53.1 percent ofbaseline spending and 46.2 percent of spendinggrowth. The remaining 13.2 percent of spendinggrowth was attributable to well care.We found much heterogeneity in spendinggrowth per episode across episodes and withineach episode type as well. Among acute episodeswith at least 1,000 observations per year, spending per episode rose 323 percent in the fastestgrowth episode, disorders of bilirubin excretion,and fell 75.5 percent in the slowest-growth episode, bacterial meningitis. Among chronic episodes with at least 1,000 observations per year,spending per episode rose 190 percent in thefastest-growth episode, other maternal conditions affecting newborns, and fell 44.1 percentin the slowest-growth episode, hepatitis G.Exhibit 4 displays our decomposition of costincreases for the ten episodes with the largestand the ten with the smallest contributions to percapita spending growth. The lone well care episode was the single largest contributor to percapita spending growth, accounting for morethan twice as much spending growth—13.2 percent—as the next-fastest-growth episode. OtherExhibit 1Descriptive Statistics Of The Sample, Analysis Of Bundled Payment In A Nonelderly,Commercially Insured Population, 2003 And 2007Characteristic20032007Number of unique individuals (millions)Mean age (years)5.835.611.334.9Age distribution (%)Younger than 18Age 18–29Age 30–39Age 40–49Age 50–59Age 60–64Male 7.146.118.976.23,25342.179.93,739Spending grouped to episodes ( billions)Portion of total spending grouped (%)Spending per capita ( )SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data from the MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters Database,2003 and 2007. NOTE Includes people continuously enrolled in noncapitated plans with drug coveragefor the full year.top contributors included breast cancer, contributing 5.3 percent; osteoarthritis of the lowerback, 4.5 percent; and type 2 diabetes, 4.4 percent. In contrast, reductions in spending on angina pectoris and acute myocardial infarctionactually slowed per capita spending growth by5.9 percent and 2.3 percent, respectively.There was also considerable heterogeneity inspending growth per episode across the ten episodes with the largest and the ten episodes withthe smallest contributions to per capita spendinggrowth. Among the top ten episodes, spendingper episode rose 48.4 percent in the two fastestgrowth episodes, colon cancer and multiple sclerosis, and fell 23.9 percent in the slowest-growthepisode, renal failure. Among the ten episodeswith the smallest contribution to overall spend-Exhibit 2Decomposition Of Per Capita Spending Growth In A Nonelderly, Commercially InsuredPopulation, 2003–07Contributing factorsTotal change in spending per capitaChange in spending due toCost per episodeEpisode mixEpisodes per personInteraction termsGrowth in spendingper capita ( )486.16Contribution to totalspending growth (%)—a355.57 20.51172.66 21.5673.1 4.235.5 4.4SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data from the MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters Database, 2003 and 2007. NOTES Each line represents the contribution to the change in spending percapita holding the other components of the decomposition fixed at their 2003 levels. Directadjustment was used to standardize age and sex to 2003 levels to account for spending growthattributable to demographic changes in the population. aNot applicable.M ay 2 0 1 332:5Downloaded from content.healthaffairs.org by Health Affairs on July 11, 2013at LIBRARY OF MEDICINEHealth Affa irs947

Hospital PaymentExhibit 3Decomposition Of Spending Growth In A Nonelderly, Commercially Insured Population, ByEpisode Type, 2003–07Episode typeGrowth in spendingper capita ( )Well careChronic episodesChronic maintenanceChronic with acute flareChronic nonstratifiedAcute episodesContribution to overallspending growth (%)64.3113.22197.247.89 12.16201.51224.7240.561.62 2.5041.4446.21SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data from the MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters Database, 2003 and 2007. NOTE Direct adjustment was used to standardize age and sex to 2003levels to account for spending growth attributable to demographic changes in the population.ing growth, spending per episode rose 19.8 percent in the fastest-growth episode, benign breastneoplasm, and fell 39.1 percent in the slowestgrowth episode, sleep disorders.The robustness of our results was maintainedwhen we dampened the effect of outliers by topcoding spending at the ninety-ninth percentilewithin each episode type. Sensitivity analysisresults are presented in more detail in theAppendix.8DiscussionEpisode-based bundled payment systems havegained traction in the public and private sectors.Yet many important questions must be addressed before episode-based payment can become a sustainable solution to rapid spendinggrowth.2,11–13Whether or not bundled payment can controlspending growth depends in part on the extentto which spending growth is driven by increasesin cost per episode as opposed to increases inepisode volume. Spending growth that is attributable to increased number of episodes will notbe materially curtailed by episode-based payment; spending growth due to costs per episodeis more likely to be affected.On this first point, our news is generally good.We found that spending per episode—includingprice increases, not episode volume—was themain driver of spending growth, accountingfor 73.1 percent of overall spending growth.14The success of episode-based payment modelsin curbing the rate of spending growth, as opposed to just providing a one-time reduction inlevel of spending, will rely greatly on the abilityto update payment rates over time. Initial episode-based spending models may rely on thefee-for-service system as a reference when updating rates. However, an alternative updating approach will be needed as the fee-for-service948Health Affai rsM ay 20 1 332 : 5system shrinks and becomes less representativeof the prevailing costs of care.Importantly, uniform updates based on historical spending growth will be appropriate onlyif spending growth per episode is relativelyevenly distributed across episodes. Our findingson this second point are more problematic. Ouranalysis found spending growth to be highlyskewed across episodes: 10 percent of episodesaccounted for more than 80 percent of spendinggrowth, and within-episode spending growthranged from 75 percent to 323 percent acrossepisodes.This skewness has important implications forbundled payment mechanisms. Most notably, itimplies that reimbursement rates cannot be updated uniformly across episodes. Some episodes,such as encounter for preventive health servicesand malignant breast neoplasm for females, experienced rapid growth. Others, such as anginapectoris and acute myocardial infarction, didnot. In this context, uniformly updating payment rates would result in overpayment for angina and acute myocardial infarction care andunderpayment for breast cancer care and preventive health services.Our finding that the encounter for preventivehealth services topped the spending growth listwarrants further investigation into specific clinical drivers of spending in primary care. Themarked growth in well-care spending concurrentwith an impressive decline in spending on acuteexacerbations of chronic conditions raises thequestion of whether the two are related—in otherwords, whether there might be a causal relationship between preventive care delivered in a wellcare episode and a decline in spending on acuteexacerbations of chronic illness.In designing a system to differentially updatereimbursement rates, it is critical to understandwhy spending per episode rises at different ratesfor different episodes. It might be the case, forexample, that during our short time window,spending growth reflected only differential increases in the price per service (for example,inpatient or outpatient services or prescriptiondrugs) within episodes and that these differential increases would reverse themselves overtime.However, most research on spending growthindicates that a large share of health care spending increases must be due to the diffusion ofmedical technology. If so, updates for differentepisodes should be based on some sense ofwhere technology is driving changes in practicepatterns.Downloaded from content.healthaffairs.org by Health Affairs on July 11, 2013at LIBRARY OF MEDICINE

Exhibit 4Spending Decomposition For Diseases With Largest And Smallest Contributions To Overall Spending Growth In ANonelderly, Commercially Insured Population, 2003–07EpisodetypeGrowth inspending percapita ( )Contribution tooverall spendinggrowth (%)Growth inspending perepisode (%)Top 10Encounter for preventive health servicesNeoplasm, malignant: breast, femaleOsteoarthritis, lumbar spineDiabetes mellitus type 2Osteoarthritis, except spineDelivery, cesarean sectionRenal failureNeoplasm, malignant: colon and rectumMultiple sclerosisOther spinal and back disorders: low backWell .9831.634.323.54.927.210.4 onicAcuteChronicaChronic 1.44 1.52 1.82 2.05 2.16 2.51 2.58 3.84 11.29 28.47 0.30 0.31 0.37 0.42 0.44 0.52 0.53 0.79 2.32 5.8619.81.3 39.17.26.6 7.5 23.7 5.21.1 11.2Bottom 10Neoplasm, benign: breastInfluenzaSleep disordersEndometriosisCongestive heart failureSinusitisHepatitis CDepressionAcute myocardial infarctionAngina pectoris, chronic maintenanceSOURCE Authors’ analysis of data from the MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters Database, 2003 and 2007. NOTE Directadjustment was used to standardize age and sex to 2003 levels to account for spending growth attributable to demographic changes inthe population. aEpisode type considered chronic with an acute exacerbation.ConclusionEpisode-based payment models constitute apromising advance in the evolution of paymentreform; implementing and realizing cost containment from these systems, however, will bechallenging. The marked skewness in spendinggrowth demonstrated in this study indicates thatreimbursement rates should not be updated uniformly across episodes of care. In the short term,as payers experiment with a limited number ofepisodes, individual updates for each episodemay be appropriate. As the breadth of coveredepisodes expands, though, more systematic approaches to updating payment rates will likely berequired.Furthermore, whereas episode reimbursement rate updates can help control spendinggrowth, they do nothing to control the numberof episodes or those episodes’ clinical appropriateness. Over time, moving from updates basedThe authors gratefully acknowledge thesupport of the Robert Wood JohnsonFoundation (Grant No. 70266) and theNational Institute on Aging (P01on historical cost growth, which may reinforceoveruse, to updates based on the appropriate useof evidence-based best practices would be ideal.In the future, it will be important to decidewhether increases in episode spending are justified by improved health or whether they reflectunnecessary use. Coupling payment with qualitymeasures may be helpful. However, given timelags, it will also be important to have a systemthat assesses the need to increase reimbursements to allow the diffusion of valuable newmedical technologies and other innovations.Developing such a system will require the integration of greater clinical knowledge intopayment update systems. Yet as episode-basedpayments become a larger part of our future payment system, we must begin the discussion ofhow such payments can be updated to allow theappropriate diffusion of medical technology. AG031098). The authors also thank EliLiebman for research assistance, andAbe Dunn for help with the MarketScandata and helpful comments on capitatedplans. The authors have no conflicts ofinterest pertinent to the current article.M ay 20 1 332 : 5Downloaded from content.healthaffairs.org by Health Affairs on July 11, 2013at LIBRARY OF MEDICINEHealth A ffairs94 9

Hospital PaymentNOTES1 A summary of nineteen high-profilepublic and private bundled paymentexperiments is provided in: BailitMH, Burns ME, Painter MW.Bundled payment across the US today: status of implementations andoperational findings [Internet].Newtown (CT): Health CareIncentives Improvement Institute;2012 [cited 2013 Apr 1]. (IssueBrief). Available from: IssueBrief-4-2012.pdf2 Center for Medicare and MedicaidInnovation. Bundled Payments forCare Improvement (BPCI) initiative:general information [Internet].Baltimore (MD): Centers forMedicare and Medicaid Services;2011 [cited 2013 Apr 1]. Availablefrom: ments/3 Emanuel EJ. The Arkansas innovation.

HEALTH AFFAIRS 32, NO. 5 (2013): 944-951 2013 Project HOPE— The People-to-People Health Foundation, Inc. Allison B. Rosen (Allison.Rosen@umassmed.edu)isanassociateprofessor of quantitative health sciences at the University of Massachusetts Medical School, in Worcester. Ana Aizcorbeis the chief economist at the Bureau of Economic Analysis, in