Transcription

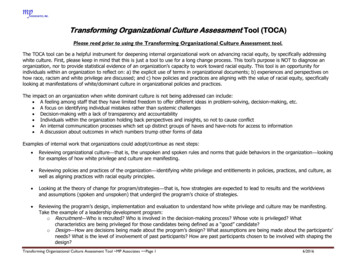

RESOURCE GUIDEAdvancing Racial Equity andTransforming GovernmentA Resource Guide to Put Ideas into ActionRACIALEQUITYALLIANCE.ORG

This Resource Guide is published by theGovernment Alliance on Race and Equity,a national network of government working toachieve racial equity and advance opportunities for all.AUTHORSJulie NelsonDirector, Government Alliance on Race and EquityLauren Spokane, Lauren Ross, and Nan DengUW Evans School of Public Policy Student ConsultantsACKNOWLEDGMENTSThank you to the following people who contributed to this guide byparticipating in interviews, feedback, and editing:Brenda Anibarro, Jordan Bingham, Lisa Brooks, Karla Bruce, Jane Eastwood, JonathanEhrlich, Pa Vang Goldbeck, Deepa Iyer, Michelle Kellogg, Wanda Kirkpatrick, Sanjiv Lingayah,Judith Mowry, Karen Shaban, Benjamin Duncan, Kelly Larson, Jenny Levison,Marlon Murphy, MaryAnn Panarelli, Heidi Schalberg, Libby Starling, Carmen WhiteLAYOUT/DESIGNLauren Spokane, Rachelle Galloway-Popotas,and Ebonye Gussine WilkinsCONTACT INFOJulie Nelsonjulie.nelson62@gmail.com, 206-816-5104GARE IS A JOINT PROJECT OFRACIALEQUITYALLIANCE.ORGCOVER IMAGE BY SEATURTLE/CREATIVE COMMONS LICENSEEDITING & COPYEDITINGSara Grossman and Ebonye Gussine WilkinsHaas Institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society

TABLE OF CONTENTSAbout the Government Alliance on Race & Equity.5Introduction. 7Section 1: Use a Shared Racial Equity Framework. 13Section 2: Build Organizational Capacity for Racial Equity.21Section 3: Implement Racial Equity Tools. 27Section 4: Use Data and Metrics. 35Section 5: Partner with Others. 43Section 6: Communicate and Act with Urgency. 49Bringing the Pieces Together. 53Conclusion. 53References. 54SPOTLIGHTS ON BEST PRACTICESDubuque, IA. 18Saint Paul, MN. 19Multnomah County, OR. 25Seattle, WA. 29Madison, WI . 31Minneapolis Park & Recreation Board, MN. 32Fairfax County, VA. 40Portland, OR. 45APPENDICESGlossary of Frequently Used Terms. 57Seattle Racial Equity Tool. 58

4Across the country,governmental jurisdictions are:Making acommitmentto achievingracial equityFocusing onthe powerand influenceof their owninstitutionsWorking inpartnershipwith othersWhen this occurs, significant leverageand expansion opportunities emerge,setting the stage for the achievement ofracial equity in our communities.RESOURCEGUIDEAdvancingRacial Equity &TransformingGovernmentGovernmentAlliance onRace and Equity

5ABOUT THE GOVERNMENTALLIANCE ON RACE & EQUITYThe Government Alliance on Race and Equity (GARE) is a national network of governmentworking to achieve racial equity and advance opportunities for all. Across the country, governmental jurisdictions are: making a commitment to achieving racial equity; focusing on the power and influence of their own institutions; and, working in partnership with others.When this occurs, significant leverage and expansion opportunities emerge, setting the stagefor the achievement of racial equity in our communities.GARE provides a multi-layered approach for maximum impact by: supporting a cohort of jurisdictions that are at the forefront of work to achieve racial equity. A few jurisdictions have already done substantive work and are poised to be a modelfor others. Supporting a targeted cohort of jurisdictions and providing best practices, toolsand resources is helping to build and sustain current efforts and build a national movement for racial equity; developing a “pathway for entry” into racial equity work for new jurisdictions from acrossthe country. Many jurisdictions lack the leadership and/or infrastructure to address issuesof racial inequity. Using the learnings and resources from the cohort will create pathwaysfor increased engagement and expansion of GARE; and, supporting and building local and regional collaborations that are broadly inclusive andfocused on achieving racial equity. To eliminate racial inequities in our communities, developing a “collective impact” approach firmly grounded in inclusion and equity is necessary. Government can play a key role in collaborations for achieving racial equity, centeringcommunity and leveraging institutional partnerships.To find out more about GARE, visit gRacial Equity &TransformingGovernmentGovernmentAlliance onRace and Equity

6“Government is one of the places wherethe community comes together anddecides who it chooses to be as a people.Government is a key keeper of our values,and our policies and investments needto reflect that. Government has greatopportunity to have an impact on the dailylives of all people and the power to shapepolicies that reduce our inequities.”- Mayor Betsy Hodges, Mayor of MinneapolisRESOURCEGUIDEAdvancingRacial Equity &TransformingGovernmentGovernmentAlliance onRace and Equity

7INTRODUCTIONAcross the country, more and morecities and counties are making commitmentsto achieve racial equity. The Government Alliance on Race and Equity (GARE) is a nationalnetwork of government working to achieveracial equity and advance opportunity for all.When government focuses on the power andinfluence of their own institution and works inpartnership with others, significant leverageand expansion opportunities emerge, settingthe stage for the achievement of racial equityin our communities.Over the past decade, a growing field of practice has emerged. This toolkit is based on thelessons learned from practitioners, as wellas academic experts and national technicalassistance providers. You may be participatingin a structured workshop and using it as a partof the workshop; or you may be using it as areference. It is a resource that will hopefully beinformative, but more importantly, one that wehope will assist government leaders in operationalizing racial equity.We know that is importantfor us to work together.If your jurisdiction has already initiated workto achieve racial equity, join the cohort ofjurisdictions at the forefront. Sharing bestpractices, peer-to-peer learning, and academic resources helps to strengthen work acrossjurisdictions.If your jurisdiction is just getting started,consider joining one of the new cohorts GAREis launching, focusing on jurisdictions at thatinitial stage. The cohort will be supported witha body of practice including racial equity training curricula, infrastructure models, tools, andsample policies.If your jurisdiction needs assistance with racialequity training, racial equity tools, model policies, communications coaching or assistancewith particular topic areas, such as criminaljustice, jobs, housing, development, health oreducation, please contact GARE. If you are in aregion where there are opportunities to buildcross-jurisdictional partnerships with otherinstitutions and communities, GARE can helpbuild regional infrastructure for racial equity.Together, we can make a difference.Why government?From the inception of our country, government at the local, regional, state, and federallevels have played a role in creating and maintaining racial inequity, including everythingfrom determining who is a citizen, who canvote, who can own property, who is property,and where one can live, to name but a few.Governmental laws, policies, and practicescreated a racial hierarchy and determinedbased on race who benefits and who is burdened. When Jefferson wrote, “all men arecreated equal,” he meant men, and not women;he meant whites and not people of color; andhe meant people with property and not thosewithout.Abraham Lincoln’s aspirations in the Gettysburg Address were about the transformationRESOURCEGUIDEAdvancingRacial Equity &TransformingGovernmentGovernmentAlliance onRace and Equity

of government, and a “government of thepeople, by the people, and for people” is stillon the table. For us to achieve racial equity,the fundamental transformation of government is necessary.Current inequities are sustained by historicallegacies, structures, and systems that repeatpatterns of exclusion. The Civil Rights movement was led by communities, and government was frequently the target. One of themany successes of the Civil Rights movementwas making racial discrimination illegal.However, despite progress in addressingexplicit discrimination, racial inequities continue to be deep, pervasive, and persistentacross the country. Racial inequities existacross all indicators for success, includingin education, criminal justice, jobs, housing,public infrastructure, and health, regardless of region. In 2010, for example, AfricanAmericans made up 13 percent of the population but had only 2.7 percent of the country’swealth. Additionally, the median net worthfor a white family was 134,000, while themedian net worth for a Hispanic family was 14,000, and for an African American family itwas 11,000 (Race Forward).Clearly, we have not achieveda “post-racial” society,and taking a “color-blind”approach simply perpetuatesthe status quo.Unfortunately, what we have witnessed is themorphing of explicit bias into implicit bias,with implicit bias perpetuated by institutional policies and practices. These policies andpractices replicate the same racially inequitable outcomes that previously existed.Too often, government has focused on symptoms and not causes when attempting to workon racial equity. We will fund programs andservices, that act as simple bandages ratherthan addressing the underlying drivers of inequities. While programs and services are oftennecessary, they will never be sufficient forachieving racial equity. We must focus on policy and institutional strategies that are drivingthe production of inequities.We are now at a critical juncture where thereis a possible new role for government—to proactively advance racial equity.8Why race?Race is complicated. It is a social construct,and yet many still think of it as biological. Racial categories have evolved over time, and yetmany think of race as static. Race is often “onthe table,” and yet fairly rarely discussed withshared understanding. More frequently, it isthe elephant in the room.Race, income, and wealth are closely connected in the United States. However, racial inequities are not just about income. When we holdincome constant, there are still large inequitiesbased on race across multiple indicators forsuccess, including education, jobs, incarceration, and housing. For us to advance racialequity, it is vital that we are able to talk aboutrace. We have to both normalize conversationsabout race, and operationalize strategies foradvancing racial equity.In addition, we must also address income andwealth inequality, and recognize the biasesthat exist based on gender, sexual orientation,ability and age, to name but a few. Focusing on race provides an opportunity to alsoaddress other ways in which groups of peopleare marginalized, providing the opportunityto introduce a framework, tools, and resources that can also be applied to other areas ofmarginalization. This is important, because tohave maximum impact, focus and specificityare necessary. Strategies to achieve racialequity differ from those to achieve equity inother areas. “One-size-fits all” strategies arerarely successful.A racial equity framework that is clear aboutthe differences between individual, institutional, and structural racism, as well as the historyand current reality of inequities, has applications for other marginalized groups.Race can be an issue that keeps other marginalized communities from effectively comingtogether. An approach that recognizes the inter-connected ways in which marginalizationtakes place will help to achieve greater unityacross communities.Please note: In thisResource Guide, weinclude some datafrom reports that focused on whites andAfrican Americans,but otherwise, provide data for all racial groups analyzedin the research.For consistency,we refer to AfricanAmericans andLatinos, althoughin some of theoriginal research,these groups werereferred to as Blacksand Hispanics.RESOURCEGUIDEAdvancingRacial Equity &TransformingGovernmentGovernmentAlliance onRace and Equity

Why now?In addition to a moral imperative we may feelfor righting wrongs, there is particular urgencyin our current moment to integrate and incorporate racial equity frameworks and tools dueto our country’s changing racial demographics.By 2060, people of color will represent approximately 57 percent of the US population,numbering 241.3 million out of a total population of 420.3 million (US Census Bureau, 2012).Latinos and Asians are driving the demographic growth. According to the Pew ResearchCenter, the Latino population is on the risedue to a record number of US births, whileimmigration is the primary reason behindAsian American growth (Brown, 2014). Simultaneously, the white population will stay thesame until 2040, at which point it will begin todecrease (US Census Bureau, 2012).We are well on our way tobecoming a multiracial,pluralistic nation, in whichpeople of color will comprisethe majority population.These changes are visible around us already. InSeptember 2014, the US Department of Education reported that the number of students ofcolor surpassed the white student populationin public schools for the first time (Krogstadand Fry, 2014; US Department of Education,2014). Additionally, many counties and metropolitan areas have become multiracial jurisdictions already. As of 2013, the 10 largest metropolitan areas where the percentage of peopleof color was greater than 50 percent of theoverall population included New York, Los Angeles, Houston, Miami, Dallas, the WashintonDC-Maryland-Virginia area, Riverside, Atlanta,San Francisco, and San Diego.Changes in migration flows are also responsible for these changes. In 1960, 75 percent ofthe immigrant population was from Europeancountries. In 2010, the top five countries ofbirth for foreign-born residents in the UnitedStates were Mexico, China, India, the Philippines, and Vietnam (Grieco, 2012). Now, morethan 80 percent of the foreign-born come fromLatin America or Asia. The refugee populationsfrom non-European countries are also on therise. In 2013, of the nearly 70,000 refugees admitted into the United States, 75 percent camefrom Iraq, Burma, Bhutan, and Somalia (Martinand Yankay, 2014).9As the racial landscape in the United Stateschanges, it is also important to recognizethat greater numbers do not equal greaterpower. That is, even as people of color become larger numerical populations, their dailylives will not change unless the systems andinstitutions that create barriers to opportunity undergo transformation. From housingto criminal justice to health access, peopleof color and immigrant communities facedisproportionately unequal outcomes. Theseconditions will not automatically change withthe increase in the populations of people ofcolor—stakeholders must work together tocorrect course through thoughtful and inclusive programs and services.What do we meanby “racial equity”?GARE defines “racial equity” as when race canno longer be used to predict life outcomesand outcomes for all groups are improved.Equality and equity are sometimes usedinterchangeably, but actually convey significantly different ideas. Equity is about fairness,while equality is about sameness. We are notinterested in “closing the gaps” by equalizingsub-par results. When systems and structuresare not working well, they are often not working well across the board. Many of the examples of strategies to advance racial equity areadvantageous not only for people of color, butalso for all communities, including whites.For more on this definition, see page 15. Fordefinitions of other terms used in this guide,see the Glossary in the Appendix.How does advancingracial equity improve ourcollective success?Government focusing on racial equity iscritically important to achieving differentoutcomes in our communities. However, thegoal is not to just eliminate the gaps betweenwhites and people of color, but to increase thesuccess for all groups. To do so, we have toRESOURCEGUIDEAdvancingRacial Equity &TransformingGovernmentGovernmentAlliance onRace and Equity

easily understood definitions of racial equity and inequity, implicit and explicit bias,and individual, institutional, and structuralracism.develop strategies based on the experiences ofthose communities being served least well byexisting institutions, systems, and structures.Advancing racial equity moves us beyond justfocusing on disparities. Deeply racialized systems are costly and depress outcomes and lifechances for all groups. For instance, althoughthere are a disproportionate number of AfricanAmericans, Latinos, and Native Americans whodo not graduate from high school, there arealso many white students who don’t graduate.We have seen strategies that work for youth ofcolor also work better for white youth.Disproportionalities in the criminal justicesystem are devastating for communities ofcolor, most specifically African Americanmen, but are financially destructive and unsustainable for all of us. Dramatically reducing incarceration and recidivism rates andre-investing funds in education can work toour collective benefit.When voting was/is constrained for communities of color, low-income white voters are alsolikely to be excluded. During the period of polltaxes and literacy tests, more eligible whiteswere prohibited from voting than AfricanAmericans.Systems that are failing communities of colorare failing all of us. Deeply racialized systemsdepress life chances and outcomes and arecostly. Advancing racial equity will increaseour collective success and be cost effective.What are our strategies—whatis our theory of change?Across the country, we have seen the introduction of many policies and programmatic efforts to advance racial equity. These individualapproaches are important, but are not enough.To achieve racial equity, implementation of acomprehensive strategy is necessary.We have seen success with advancing racialequity and government transformation withthe following six strategies:1.Use a racial equity framework. Jurisdictions need to use a racial equity framework that clearly names the history ofgovernment and envisions and operationalizes a new role; and utilizes clear and2.Build organizational capacity. Jurisdictions need to be committed to the breadth(all functions) and depth (throughouthierarchy) of institutional transformation.While the leadership of elected membersand top officials is critical, changes takeplace on the ground, and infrastructurethat creates racial equity experts andteams throughout local and regional government is necessary.3.Implement racial equity tools. Racialinequities are not random —they have beencreated and sustained over time. Inequities will not disappear on their own. Toolsmust be used to change the policies, programs, and practices that are perpetuatinginequities, as well as used in the development of new policies and programs.4.Be data-driven. Measurement must takeplace at two levels—first, to measure thesuccess of specific programmatic andpolicy changes, and second, to developbaselines, set goals, and measure progresstowards community goals.5.Partner with other institutions and communities. The work of local and regionalgovernment on racial equity is necessary,but it is not sufficient. To achieve racialequity in the community, local and regional government must be working inpartnership with communities and otherinstitutions.6.Communicate and act with urgency.While there is often a belief that change ishard and takes time, we have seen repeatedly, that when change is a priority andurgency is felt, change is embraced andcan take place quickly. Building in institutional accountability mechanisms via aclear plan of action will allow accountability. Collectively, we must create greaterurgency and public will to achieve racialequity.The remainder of this Resource Guide provides additional information about each ofthese strategies. Why are they important?What is the theory? What is the practice?How does change happen? How can govern-10RESOURCEGUIDEAdvancingRacial Equity &TransformingGovernmentGovernmentAlliance onRace and Equity

ment normalize conversations about race,operationalize new behaviors, and organize toachieve racially equitable outcomes? The toolkit shares the stories and lessons learned fromlocal government leaders across the countrywho have built (and continue to build) racialequity strategies. We hope that by learningfrom others’ experiences, we can all strengthen our ability to achieve racial equity.11RESOURCEGUIDEAdvancingRacial Equity &TransformingGovernmentGovernmentAlliance onRace and Equity

12“This analysis is direct aboutconfronting the ineffectiveness ofour current practices, our policies,and our procedure. It is a bold stepto address the root causes that leadto racial disparities.”- Supervisor Sheila Stubbs, Dane County, WIRESOURCEGUIDEAdvancingRacial Equity &TransformingGovernmentGovernmentAlliance onRace and Equity

131. USE A SHARED RACIALEQUITY FRAMEWORKAcross the United States, race canbe used to predict one’s success. Deep andpervasive inequities exist across all indicatorsfor success, including jobs, housing, education,health, and criminal justice. Taking a “color-blind” approach has not helped. In orderfor us to achieve equitable outcomes, it isnecessary for us to understand the underlyingdrivers of inequity.Talking about race in our society can be difficult, but it doesn’t have to be the case. Much ofthe challenge exists because we do not have acommon understanding or shared definitions.There are four main concepts that are criticalfor shared understanding:A.Historical role of government laws,policies and practices in creating andmaintaining racial inequitiesB.A definition of racial equity and inequityC.The difference between explicit andimplicit biasD.The difference between individual,institutional, and structural racismA. Historical Role ofGovernment in Creating andMaintaining Racial InequitiesFrom the beginning of the formation of theUnited States, government played an instrumental role in creating and maintaining racialinequities. Through decisions about who couldgain citizenship, who could vote, who couldown property, who was property, and whocould live where, governments at all levelshave influenced distribution of advantage anddisadvantage in American society. Early on inUS history, rights were defined by whiteness.As an example, the first immigration law of thenewly formed United States, the NaturalizationAct of 1790, specified that only “whites” couldbecome naturalized citizens (Takaki, 1998).While the definition of race in American society was formed around the divide betweenwhites and African Americans in the context ofslavery, Native Americans as well as Asians andother immigrant groups came to be definedracially as non-white, maintaining a binary between those who enjoy the privileges of whiteness and those who are seen as undeserving ofsuch privileges (Kilty 2002).Even legislation that on its surface appeared tobe race neutral, providing benefits to all Americans, has often had racially disproportionateimpact, as evidenced by the examples below.The National Housing Act of 1934 was ostensibly passed to improve the lot of those whootherwise might not be able to afford to own ahome, but the way it was implemented using aneighborhood grading system (now known asredlining) that labeled minority neighborhoodsas too unstable for lending resulted in entrenched segregation and benefits largely onlyaccrued to white families (Jackson 1985).Another New Deal policy, the National LaborRelations Act of 1935, excluded agriculturaland domestic employees as a compromise withSouthern Democrats (Perea 2011). While theRESOURCEGUIDEAdvancingRacial Equity &TransformingGovernmentGovernmentAlliance onRace and Equity

14History of Government and Racelaw was written in “race-neutral” language,the predominance of African Americans inthese occupations created disparities in laborprotection that exist to this day, as these jobsremain largely held by people of color and havenever been incorporated into the NLRA.The Serviceman’s Readjustment Act of 1944,also known as the GI Bill, is often credited forhelping to build the modern American middle class. While this program did not includeexplicit racial language, there were significantdisparities in its impact (Herbold, 1994–95).Tuition benefits were theoretically offeredto African American veterans, but largelycould not be used where they were excludedfrom white colleges, and space was not madeavailable in overcrowded African Americancolleges. Banks and mortgage agencies refused loans to African Americans, and whenAfrican Americans refused employment atwages below subsistence level, the VeteransAdministration was notified and unemployment benefits were terminated. As an exampleof the uneven impact of the GI Bill, of the 3,229GI Bill guaranteed loans for homes, businesses,and farms made in 1947 in Mississippi, only twoloans were offered to African American veteranapplicants (Katznelson 2006).In response to the many acts of governmentthat created racial disparities and exclusion,both explicitly and in effect, the Civil Rightsmovement of the 1960s put pressure on government to address inequity. These new lawsinclude the Supreme Court ruling in Brown v.Board of Education that judged school segregation unconstitutional; the Civil Rights Actof 1964, which prohibited discrimination basedon race, color, sex, religion, or national originand desegregated public facilities; and theVoting Rights Act of 1965, which made racialdiscrimination in voting illegal.Following the victories achieved during theCivil Rights movement, many overtly discriminatory policies became illegal, but racialinequity nevertheless became embedded inpolicy that did not name race explicitly, yet stillperpetuated racial inequalities.The New Deal and GI Bill policies describedabove showcase how even before civil rightslegislation became the law of the land, policymakers had found ways to accommodate thosewho benefit from continued racial disparitieswhile appealing to broader American ideals offairness and equality.Now, with a growing movement of governmentleaders examining the racial impacts of publicpolicy on their communities, there is tremendous opportunity for the development of proactive policies, practices, and procedures thatadvance racial equity. We are seeing a growingRESOURCEGUIDEAdvancingRacial Equity &TransformingGovernmentGovernmentAlliance onRace and Equity

field of practice of local and regional governments working to advance racial equity in avariety of realms, from internal hiring policiesto criminal justice reform to education andworkforce development.B. A Definition of Racial Equityand InequityEquality and equity are sometimes usedinterchangeably, but actually convey significantly different ideas. Equity is about fairness,while equality is about sameness. We are notinterested in “closing the gaps” by equalizingsub-par results. When systems and structuresare not working well, they are often not working well for most people. Although they mightwork a little bit better for white people thanfor people of color, when they are broken, improvements work to the benefit of all groups.Racial equity means thatrace can’t be used to predictsuccess, and we havesuccessful systems andstructure that work for all.What matters are the real results in the lives ofpeople of color, not by an abstract conceptionthat everyone has equal opportunity. As thehistorical examples above show, barriers tosuccess attainment go far beyond whether thelaw contains explicit racial exclusion or discrimination. Because of the inter-generationalimpacts of discrimination and continued disparities due to implicit bias, policies must betargeted to address the specific needs of communities of color. This means that sometimesdifferent groups will be treated differently, butfor the aim of eventually creating a level playing field that currently is not the reality.C. The Difference betweenExplicit and Implicit BiasWe all carry bias, or prejudgment. Bias canbe understood as the evaluation of one groupand its members relative to another. Acting onbiases can be discriminatory and can createnegative outcomes for particular groups.In its 2013 annual review, the Kirwan Institutedefined implicit bias

jurisdictions at the forefront. Sharing best practices, peer-to-peer learning, and academ-ic resources helps to strengthen work across jurisdictions. If your jurisdiction is just getting started, consider joining one of the new cohorts GARE is launching, focusing on jurisdictions at that initial stage. The cohort will be supported with