Transcription

Z i N E OFTUFTSUNIVERSITYTrr\SCHOOLOFVETERINARYMEDICr5 U h\ M 5 ;iTicks-PublicTuftstargets

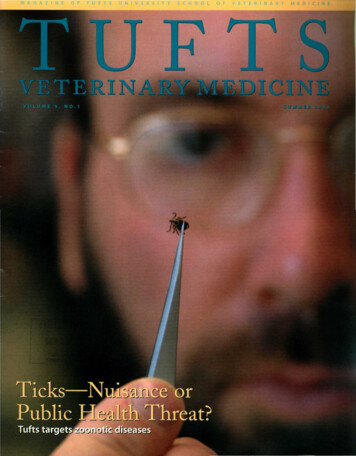

FROMZ.DTHEDEANy G 3 T SP r e p a r i n gf r o n tlinesStatelater,the mission continues:v e t e r i n a r i a n so fp u b l i cf o rt h eh e a l t hFundingU p d a t eWe are pleased to announce that MassachusettsGovernor Mitt Romney has signed the state's 2004budget, which includes a 3,004,000 appropriationfor Tufts University School of Veterinary Medicine.We are grateful to the governor for acknowledgingthe necessity of state funding in order to operate theCommonwealth's and New England's only veterinaryschool./"As health professionals, veterinarians have a responsibility to protect not onlythe health of animals, but also that of humans and the environment.There are important links between animals, humans and the environment,and the well-being of all three are dependent on sustainable ecosystems.Because of this comprehensive view, Tufts Veterinary School had the vision inits early years to establish an educational program that preparesgraduates to protect our environment and maintain public health. IBIn our core curriculum, students learn about the ecologicalcontext of health, the control and prevention of zoonotic infectiousdiseases as critical to both animal and human health, the importanceof protecting a healthy and secure food and water supply, and thechallenges we face globally as international health professionals.Because of the flexible design of our curriculum, many veterinarystudents elect to become more knowledgeable and active in specificareas of public health.A VTen years ago, we had the foresight to establish a programwith Tufts Medical School to enable students to obtain a dualdegree in veterinary medicine and public health (D.V.M./M.RH.) injust four years. To be sure, this rigorous program is not for the faint of heart!The first students in this program graduated in 1997 and continue to maketheir mark.The seriousness of public health preparedness has been on everyone's mindsince 9/11, anthrax attacks, and numerous global outbreaks of infectiousdiseases. I have attended many meetings locally and regionally about theurgent need to prepare for bioterroism. Other veterinary schools are alsofollowing Tufts' lead by establishing combined D.V.M./M.RH. programs. Thisis a good thing, because our profession must prepare many more veterinarygraduates for public health jobs in the future.It is also vital that we keep in mind the important impact thatveterinarians in traditional private practice have on public health. Whether it'spreventing common zoonoses such as toxoplasmosis and rabies—or providingearly diagnosis and reporting of an emerging zoonotic infectious disease such asMad Cow disease—private veterinary practitioners are on the front line ofpublic health disease surveillance. This is why we have emphasized educatingall of our veterinary students about their responsibilities to protect publichealth, while encouraging some to devote their careers to this by participatingin Tufts' combined veterinary medicine and public health degree program.Throughout this academic year, Tufts Veterinary Medicine will report onsignificant achievements the school has made during its first 25 years. Thisissue focuses on the work our faculty is doing to safeguard public health. I hopeit will help you understand the many ways in which Tufts Veterinary School isleading the veterinary profession's efforts in protecting the health of animals,humans and the environment.TUVETERINARYDean2 TUFTS VETERINARY MEDICINE Summer 2 O OJTSMEDICINEVOLUME5.N0.1Summer 200JExecutive EditorDr. Philip C. Kosch, DeanSchool of Veterinary MedicineEditorBarbara Donato, Assistant DirectorPublic RelationsManaging EditorMargaret LeRouxEditorial AdviserShelley Rodman, DirectorVeterinary Development and Alumni RelationGraphic DesignerLinda DagnelloPhotographerAndrew CunninghamWritersBarbara Donato, Margaret LeRouxTufts Veterinary Medicine is funded in part by thEdward Hyde Cox Fund for Publications. It ispublished three times a year and distributed to keyuniversity personnel, veterinary students,veterinarians, alumni, friends and others.We welcome your letters, story ideas andsuggestions. Send correspondence to:Editor, Tufts Veterinary Medicine,Tufts University School of Veterinary Medicine,200 Westboro Road, North Grafton, MA 01536Telephone: (508) 839-7910To view recent back issues of Tufts Veterinarytine visit our web site at: www.tufts.edu/vetOn thePhilip C. Kosch, D. KM., Ph.D.Fcover:Dr. Stephen M. Rich, assistant professor inthe infectious diseases division at TuftsSchool of Veterinary Medicine, studies ticksto track the progression of Lyme disease

Faculty awardsDr. Gary Patronek, director of Tufts'Center for Animals and Public Policy anddirector of the graduate program in animalsand public policy, received the Carl J.Norden Distinguished Teacher Award atcommencement ceremonies this spring.He was cited for his excellence as ateacher, mentor and colleague.Three years ago, Patronek was namedthe first Agnes Varis University Chair inScience and Society at Tufts University.Last year, he was elected to the NationalAcademies of Practice and was honoredby the American Humane Association forhis dedicated and unselfish service to thewelfare of animals."Policy decisions concerning animalsin society have all too often been made onemotional or political basies, rather thanbeing science-based," said Dean PhilipKosch, who presented the award atcommencement. "Dr. Patronek and hiscolleagues teach students how to evaluatethe available data objectively and how toapply the scientific method to obtainneeded data to better inform policymakers."Tufts a l u m n aNqivenThe Pfizer Animal Health Award forResearch Excellence was presented toDr. Andrew Hoffman, associate professorof large animal medicine, who headsTufts' lung function testing service.Hoffman has successfully developedan independent, externally-sponsoredresearch program that is internationallyrecognized. He secured more than 1 millionin grants from the National Institutes ofHealth and other agencies to studycomparative respiratory pathophysiology.Working with collaborators at HarvardMedical School, Hoffman developed anon-invasive thorascopic technique forlung reduction surgery in people withend-stage emphysema. He developed anovel, mechanical ventilator for the care ofpeople with critical respiratory illnesses, aswell as non-invasive lung function testsfor horses and dogs.Along with Dr. Melissa Mazan, V93,and other Tufts colleagues, he characterizedequine airway hyper-reactivity as a modelof human asthma to study the pathogenesisof asthma in horses and humans.StudentBRIEFachievementChristopher Weber, V05, was one of 12Tufts students to receive the 2003presidential awards for citizenship andpublic service from President Lawrence S.Bacow. Recipients were nominated byfaculty, students, staff, alumni andcommunity partners for their outstandingcommunity service and leadershipachievements.Under Weber's leadership, participationin Gap Junction increased four-fold. Thisstudent-run program encourages primaryand secondary school children to enjoylearning about science.As a member of the neonatal intensivecare team at Tufts' Hospital for LargeAnimals, Weber organized training sessionsfor 60 to 80 volunteers during foalingseason. He also scheduled three shifts ofvolunteers every day from February toJune, including difficult-to-coverovernight shifts.Weber is a full-time student andemergency technician at the Hospital forLarge Animals.honoredThe late Dr. Annelisa Kilbourn, V96, waselected posthumously to the United NationsEnvironment Program's Global 500 Roll ofHonor for her outstanding contributions tothe protection of the environment. She wasone of eight individuals and organizationsto receive the honor in 2003.Kilbourn died in a plane crash inGabon in November 2002, while researchingthe link between the Ebola virus and westernlowland gorillas for the Wildlife ConservationSociety'sfieldveterinary program. Her workin thefieldproduced the first proof thatgorillas are infected and quickly die of thevirus, information which may serve toprotect both gorillas and humans.Classmates and friends of Kilbournhave established the Annelisa M. KilbournConservation Medicine Fund at Tufts tosupport an annual wildlife and internationalveterinary medicine conference at Tuftsand a keynote Annelisa M. KilbournMemorial Lecture.Gifts in support of the fund shouldbe directed to Tufts University School ofVeterinary Medicine, Development Office,200 Westboro Road, North Grafton, MA01536.summer 200JTUFTS VETERINARY MEDICINE3

T u f t sr e s e a r c hk etick-borneCdiseaseshecking their pets—and themselves—for ticks after a walk hasbecome an all too familiar ritualfor residents of central Massachusetts.That's because the spread of Lyme disease,the most frequently diagnosed tick-borneinfection in the U.S., has added a publichealth risk to the simple pleasures ofenjoying the great outdoors.Dr. Stephen M. Rich, assistantprofessor in the infectious diseases divisionat Tufts School of Veterinary Medicine,has tracked the progression of the diseasefor more than a decadeDr. Stephen Rich and is working on agathers ticks invaccine to prevent it.the field."When I was a graduatestudent studying Lymedisease in 1991, it was rare to find tickscarrying the disease inland or in urbanareas," Rich said. "We used to see it primarily along the coast."Now, ticks carrying Lyme disease canfind human and animal hosts in city parksas well as in the woods of the Northeast.More than 17,000 cases of Lyme diseasewere reported in Northeastern states andWisconsin in 2000, the most recent yearfor which statistics are available.Lyme disease is zoonotic, whichmeans it's transmitted to humans fromanimals. Zoonotic diseases can bedangerous, if not lethal to humans—recent examples include SARS andmonkey-pox—and they represent threefourths of the world's emerging diseases.Writing in the June 2, 2003, issue ofthe Boston Globe, Madeline Drexler, authorof "Secret Agents: The Menace ofEmerging Infections," noted, "Whateverdeadly pandemic next sweeps the world,whatever newly christened scourgedominates the headlines, it will almostsurely have vaulted across the Darwinianorder."4 TUFTS VETERINARY MEDICINE summer 200J

Zoonotic diseases such asanthrax, tularemia and plagueare also implicated by theCenters for Disease Controland Prevention (CDC) aspotential instruments ofbioterrorism. (See page 6 forinformation on Tufts'involvement in bioterrorismpreparedness.)Though rarely seen inhumans, these same diseasesoccur periodically in animals.Veterinarians and veterinarymedical researchers, with theirexpertise in diagnosing andtreating zoonotic diseases inanimals, now find themselvesin the spotlight when publichealth issues and bioterrorismare discussed."Tufts, with its strengthsboth in veterinary medicineand biological research, ispoised for a major role studying and communicating aboutzoonotic diseases," Rich said.rid of the problem, you haveto get rid of it at the root."Rich's group is attackingtick-borne diseases with atwo-pronged approach, goingafter Lyme disease in the wildwith a bait-infused oral vaccine for white-footed mice.They're also beginning towork with Tufts colleagues,Dr. Jean Mukherjee and Dr.Sam Telford III, to develop avaccine against tick bites toprevent other diseases causedby ticks.then the disease won't betransmitted to the tick's host."The Lyme disease vaccineresearch involves Rich andcolleagues from Yale University and the University of California at Irvine. It's an effortmodeled after the Tufts rabiesvaccine program on Cape Codheaded by Dr. Steve Rowell,V83, and Dr. Alison Robbins,V92. This effort—the longestrunning program of its kind—has kept Cape Cod rabies-freefor the past 10 years. (Seerelated story, page 17.)"We're making a case thatthis might be a strategy forpublic health departments tofollow," Rich said. "Similar tospraying for mosquitoes, theycould be vaccinating miceagainst ticks."The Tufts researcher isoptimistic about the potentialfor tick vaccines. "We have thepotential to wipe out tickborne diseases," he said." W h e n p e o p l e t h i n k a b o u t L y m e disease, t h e y t e n d tot h i n k a b o u t v a c c i n e s a n d c o n t r o l l i n g it i n t h ehumanp o p u l a t i o n . T o a basic scientist, w h a t ' s h a p p e n i n g in t h ew i l d is o f g r e a t e r r e l e v a n c e . If y o u w a n t t o g e t r i d o f t h ep r o b l e m , y o u h a v e t o g e t r i d o f it a t t h e r o o t . "The L y m e diseaseconnectionUnlike other zoonoticdiseases, Lyme disease symptoms are similar in bothhumans and animals. Thosesuffering from the diseasehave a fever and arthritis-likepain and stiffness in theirjoints. Unless treated withantibiotics, the infection canbecome serious and affect thebrain and heart. Ticks pick upthe bacteria that cause Lymedisease from white-footedmice and ultimately pass it onto other hosts as they feed ondeer, dogs and humans."When people thinkabout Lyme disease, they tendto think about vaccines andcontrolling it in the humanpopulation," Rich said. "To abasic scientist, what's happening in the wild is of greaterrelevance. If you want to getRich vividly describedticks in action as he explainedhow a vaccine against tickborne disease would work:When ticks land onhumans or animals, they takeabout a day to burrow theirmouth into the skin of theirhost, creatinga tiny pool.Dr. Rich at work inThis poolhis laboratory.becomes amixture of blood andenzymes, as ticks literally spitin and out of it, slurping upthe blood of their victim. It'shere, in the pool, that tickstransmit the bacteria thatcause Lyme disease."We're exploring ways ofdeveloping a vaccine that willcreate antibodies against theenzymes in the saliva of ticks,"Rich said. "If these antibodiescan stop the tick from feeding,summer 20ojTUFTS VETERINARY MEDICINE5

V e t e r i n a r i a n sa h e a d o f t h e c u r v e in b i o t e r r o r i s mpreparednessArecent series of bioterrorismpreparedness programs for areaveterinarians and other animalcaretakers is another example of TuftsVeterinary School's role in protectingpublic health.Developed by Tufts and sponsored bythe Massachusetts Bureau of AnimalHealth, the programs are designed to educate people involved in animal healthabout signs of zoonotic diseases that havethe potential for use as bioterrorismagents. These diseases, such as plague,anthrax and tularemia, occur periodicallyin animals—and when they occur inhumans, they can be just as deadly.Tufts faculty and other speakers areholding separate sessions for groups suchas animal control officers, livestock owners,animal shelter workers and pet store owners.They will identify the signs of dangerouszoonotic diseases likely to be used in abioterrorist attack, and what peopleshould do if they detect them in animals."In the event of a bioterrorist act, it'slikely that animal caretakers will be thefirst to notice signs," said Dr. GeorgeSaperstein, assistant dean for research andchair of the veterinary school's Departmentof Environmental and Population Health."Our goal is to make them aware ofunusual signs, so they will immediatelycontact a veterinarian."Fast action is critical in controllingthe spread of disease, Saperstein noted.This point was brought home duringTufts' participation in the test of anemergency response plan for controlling asimulated outbreak of foot-and-mouthdisease last year. The Bureau of AnimalHealth and the Massachusetts EmergencyManagement Agency,Dr. George Sapersteinworking with theexamines a ewe for Massachusettssigns of disease.Bureau of Animal6 TUFTS VETERINARY MEDICINE summer 200J

Control and other organizations such asTufts, developed the plan.Besides being potentially lethal tolivestock, the economic impact of such abioterrorist act could be devastating."Any terrorist act on U.S. domesticmeat production could have verydamaging impacts on the U.S. and worldeconomy," said Dr. Gilbert E. Metcalf,chair of Tufts University's Department ofEconomics.The United States produces roughlyone-quarter of the world's supply of beef.There are some three million workersemployed directly in the agricultural sector.An additional half-million workers areemployed in meat products manufacturingand processing, 3.5 million employed infood stores, and over eight million inrestaurants and bars."There was an enormous learningcurve to get people to understand thedegree and seriousness of the risk of foreignanimal diseases and zoonotic diseases likeplague or anthrax," he said.Sherman is the former head of Tufts'international veterinary medicine programand former director of Tufts' Center forConservation Medicine."I knew from my international workthat (a disease like foot-and-mouth) wasendemic to Africa and Asia, but findingthe highly contagious disease in England—with its close historical, cultural and traderelations with New England—was worrisome," he said."Someone could have been hiking inthe English countryside, picked up footand-mouth on their shoes or nasalpassages, get on a plane and be at a farmCAOFLENDARF V F N T SSeptember 6Open HouseSeptember 21PetTrekOctober 2-4Tufts'Canine andFeline Breeding andGenetics ConferenceDecember 7Timely Topics inInternal Medicine,5th annual conferenceFor more information aboutOpen House, visit the Tufts web site:www.tufts.edu/vet" I n t h e e v e n t o f a b i o t e r r o r i s t a c t , it's l i k e l y t h a t a n i m a lc a r e t a k e r s will b e t h e first t o n o t i c e signs.""Clearly, any bioterrorist act thatthreatened the nation's beef supply wouldhave large spill-over effects into manyparts of the U.S. economy," Metcalf said.Veterinarians and economists learneda hard lesson from the foot-and-mouthdisease outbreak in Great Britain twoyears ago."At the time of the foot-and-mouthoutbreak in the UK, there was very littleawareness and concern about threats toagriculture in Massachusetts," said Dr.David M. Sherman, chief of theMassachusetts Department of Food andAgriculture Bureau of Animal Health.in New England the next day—then pet acow or sheep. That's all it would take toget an epidemic started here."The state's need for a plan to controlthe spread of diseases caused by acts ofbioterrorism became evident after Sept. 11.Saperstein, who took part in thesimulated foot-and-mouth disease outbreak,noted that the exercise helped putMassachusetts at the forefront of disasterpreparedness."Veterinarians are ahead of the curvewhen it comes to public health preparedness," he said.To learn more about PetTrek, or toregister, visit the web site:www.pettrek.orgor call Nancy Thompson:(508) 839-5395, ext. 84627.For more information on continuingeducation classes, visit the web site:www.tufts.edu/vet/contineduor contact Susan Brogan in theContinuing Education Department:(508) 887-4723;susan.brogan@tufts.edusummer 2oojTUFTS VETERINARY MEDICINE 7

Mosquitor e s e a r c h links Tufts t o i n t e r n a t i o n a l p u b l i c h e a l t h e f f o r t sDr. Stephen M. Rich and hiscolleagues are studying malaria todetermine how the mosquitoborne parasites maintain their ability tocause disease despite efforts to eradicatethem over the course of the last century.This critical research impacts far beyondthe Tufts campus, and spans across theglobe to developing countries wheremillions die from malaria every year.Though it is now extremely uncommonin the U.S., malaria is a serious, sometimesfatal disease that occurs in over 100 countriesand affects more than 40 percent of theworld's population. Approximately 500Cameroon, collecting blood samples frompeople hospitalized with malaria," he said."We want to find out if the parasites differfrom site to site—Sudan to Nigeria, forexample—and if they differ from year toyear in the same site."Rich explained that in the early 1960s,health officials undertook a multinationalDr. Rich focuses on e f f o r t t 0 eradicate malaria.malaria parasites" A f t e r a five-year effort, andmillions of dollars spent, theparasites and mosquitoes became resistantto the agents used to combat them," he said."We would like to make certain that futureefforts to reduce malaria transmission aresustainable for the long-term public healthbenefit."" T h a t parasites h a v e b e c o m e so diversified in s u c h as h o r t t i m e s p a n is a s t r o n g i n d i c a t i o n t h a t m a l a r i a isn o t o n l y a m o v i n g t a r g e t , b u t t h a t i t is m o v i n gq u i c k l y in w a y s t h a t a l l o w parasites t o a d a p to v e r c o m e our efforts to t h w a r tmillion people are infected with malariaannually. Of the two million who die eachyear from the disease, 85 percent arechildren under the age of five.Mosquitoes carry, or are vectors for,malaria by biting an infected person andingesting malaria parasites. After growinginside the mosquito, the parasites can betransmitted to another person when themosquito bites again.There are more than 20 differentmalaria vaccines under development byresearchers throughout the world—at acost of hundreds of millions of dollars.With funding from the World HealthOrganization and the National Institutesof Health, Rich and his colleagues arestudying the genes that encode proteinson the parasite that causes malaria in aneffort to determine which vaccines are likelyto be most effective.8 TUFTS VETERINARY MEDICINE summerveryv e c t o r stothem."While malaria was long thought tobe an age-old parasite of humans, Richand his colleagues demonstrated that thedisease probably traces its origins to lessthan 10,000 years ago with the rise ofhuman agricultural activity. This period isa mere "blink of the eye" in evolutionarytime scales, but in that time frame malariaparasites have greatly diversified. Thedevelopment of an effective vaccinerequires finding target proteins that differlittle among malaria strains."That parasites have become so diversified in such a short time span is a strongindication that malaria is not only amoving target, but that it is moving veryquickly in ways that allow parasites toadapt to overcome our efforts to thwartthem," Rich said."We're looking at parasite strains inGhana, Sudan, Nigeria, Kenya and2oojThose vexiiyme disease is one of several"vector-borne" diseases thatTufts researchers are targeting.Vectors are living organismsthat transmit diseases.Ticks, forexample, are vectors for severaldiseases, including Lyme disease.Mosquitoes are also vectors fora variety of diseases frommalaria and encephalitis to theWest Nile virus. Vectors like ticksare particularly vexing becausethey can transmit diseases toother organisms as well as actas parasites that feed on them.

D r . T z i p o r in a m e dd i s t i n g u i s h e dp r o f e s s o rTzipori's groundbreaking research ishelping to develop an effective defenseagainst a virulent strain of E. coli. Anotherof his major initiatives investigatesCryptosporidium parvum, a water-borneprotozoa that causes diarrhea in humansand animals. It can be fatal to malnourished children and people whose immunesystems are comproDr. Saul Tziporim i s e d W i t h fundr.«-Dr. Saul Tzipori, director of theinfectious diseases division of theDepartment of Biomedical Sciences, was appointed to the rank of distinguished professor; Dean Philip Koschannounced the appointment at the 2003commencement ceremony. It was only thefifth time the honor has been given in the25-year history of Tufts VeterinarySchool.Dean Kosch noted that Tzipori "hasdevoted his career to the investigation andcontrol of enteric diseases in humans andanimals sharing similar environments withhumans. His work will result in improveddiagnostic and therapeutic approaches tolife-threatening diarrheal diseases in children and immuno-compromised adults inthis country and the world."Tzipori joined the Tufts faculty in1991 after a distinguished research careerin Australia and Bangladesh, includingbeing named a Fellow of the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons by the RoyalVeterinary College in London for meritorious contributions to learning. He earnedhis veterinary degree and Ph.D. in tropical viral diseases from the University ofQueensland in Australia.In less than three years after joiningTufts Veterinary School, and supportedentirely by external funding, he built thedivision of infectious diseases. Today,Tzipori is one of the university's bestfunded researchers, with support frompublic and private sources including theNational Institutes of Health (NIH), theU.S. Department of Agriculture, the Cen-ing from the NIH,Tzipori and colleagues are sequencing thenucleotides of the entire Cryptosporidiumgenome.Tzipori also wrote the proposal thatgained university approval for TuftsVeterinary School's Ph.D. program and hecurrently chairs the school's researchcommittee. He represented Tufts in workingwith key researchers and deans from otherveterinary schools to establish a studentresearch training grant funded by NIH.Tzipori's "leadership and team-buildingskills have resulted in the most successfulsponsored research program in the entireuniversity. They have cemented ourinstitutional reputation as a leader inbiomedical research within the universityand nationally," Kosch said. "I have greatrespect for him as a member of our facultyand consider him to be the most distinguished biomedical scientist anywhere inacademic veterinary medicine today."As distinguished professor, Tzipori'sinscribed photograph will hang in theWebster Family Library with those of theveterinary school's other four distinguished"Tzipori has d e v o t e d his career t o t h einvestigationa n d c o n t r o l o f enteric diseases in h u m a n sanimals sharing similar e n v i r o n m e n t s w i t hters for Disease Control and Prevention,the Federal Food and Drug Administrationand the Environmental Protection Agency.andhumans."professors: Dr. Sawket Anwer, Dr. SusanCotter, Dr. Irwin Leav and Dr. James N.Ross, Jr.summer 200JTUFTS VETERINARY MEDICINE 9

A 25 yearlegacy:of animals, humans, and t h e e n v i r o n m e n tRinderpest eradication helps prevent famineDr. Jeffrey C. Mariner,V90, helped develop a heat-stablevaccine for rinderpest, a devastating cattle disease that ragedacross much of Africa in the early 1980s, causing losses of at least 2 billion. Previous vaccines for the deadly disease requiredrefrigeration, which hindered distribution in the hot and remoteareas where it was needed. The vaccine has been so successful, theUnited Nation's Food and Agriculture Organization estimatesthat rinderpest could be eradicated by the year 2010, only the secondtime in history a disease has been globally eliminated. Tufts' successin helping resolve this classic conservation medicine case hasprompted the university to initiate a similar campaign that wouldabolish the measles virus in developing countries.Tufts' animal-facilitatedtherapy program helped firstgraders at South Grafton Elementary School improve theirreading skills by connecting them with a canine audience.Comforted by friendly dogs, the kids' confidence and theirreading ability grew. Here, Brandon Doyle shares a story withHag rid, an English pointer owned by Debra Gibbs,veterinary technician at Tufts'Henry and Lois Foster Hospitalfor Small Animals.What better w a y t o observe t h e2 5 t h a n n i v e r s a r y o f TuftsUniversity School of V e t e r i n a r yMedicine than to note new and importantc o n t r i b u t i o n s t o p u b l i c h e a l t h t h a t faculty,staff a n d a l u m n i are m a k i n g h e r e a n d acrosst h e g l o b e ? T h e r e are a b u n d a n t e x a m p l e s ;f o l l o w i n g are a r e p r e s e n t a t i v e f e w .10 TUFTS VETERINARY MEDICINE SUMMER 2003Therapy program demonstrates animals'role inhuman healthTufts' animal-facilitated therapy program promotes thehuman-animal bond in settings from nursing homes and mentalhealth facilities to an elementary school reading program. Withsupport from Tufts' Center for Animals and Public Policy, thecertified therapy dogs exemplify the vital role animals play inhuman health.Rabies vaccine helps reduce threat to humansFor the past decade, Dr. Steve Rowel, V83, and Dr. AlisonRobbins, V92, have led a raccoon rabies vaccination program,preventing the disease from reaching Cape Cod. Their efforts,supported by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts through theDepartment of Public Health, have also been successful inreducing rabies carried by raccoons within three towns that borderthe Cape.Educating veterinarians and the public aboutbioterrorismIn addition to Tufts' involvement in developing bioterrorismpreparedness programs, several veterinary school alumni areheading efforts to educate the public and veterinarians aboutbioterrorism, emergency management and public health. Theyinclude: Dr. Elizabeth Stone, V90, public health veterinarian forthe Maine Bureau of Health; Dr. Louisa Castrodale, V97, epidemiologist for the state of Alaska; Dr. Fredric Cantor, V84,public health veterinarian for the Commonwealth of Massachusetts;and Dr. Hugh Mainzer, V90, senior preventative medicine officerand epidemiologist in the Division of Emergency and EnvironmentalHealth Services at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Veterinarians as diplomats in the Middle EastDr. George Saperstein headed a 2.3 million project fundedby the U.S. Agency for International Development that improveddiagnostic capabilities and training in disease surveillance in theMiddle East. The five-year effort created a network of expertsfrom neighboring countries that worked together despite theirpolitical differences.Genomics research promotes shrimp and seafoodindustryInnovative research in shrimp genetics by Dr. AcaciaAlcivar-Warren is helping create disease-resistant strains andboost domestic production of the popular seafood.Study exposes second-hand smoke as cause ofcancer in catsA first-of-its-kind study conducted by researche

for Tufts University School of Veterinary Medicine. We are grateful to the governor for acknowledging the necessity of state funding in order to operate the Commonwealth's and New England's only veterinary school. TUFTS VETERINARY MEDICINE VOLUME5.N0.1 Summer 200J Executive Editor Dr. Philip C. Kosch, Dean School of Veterinary Medicine Editor