Transcription

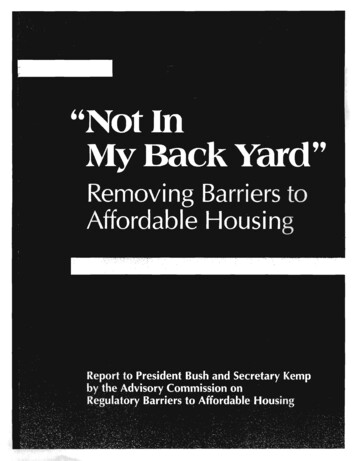

((Not In My Backyard"Removing Barriers toAfforda ble HousingHUD-5806

Advisory Commission onRegulatory Barriers to Affordable HousingU.S. Department of Housing and Urban DevelopmentJuly 8, 1991Honorable Jack KempSecretary of Housing and Urban DevelopmentU.S. Department of Housing and Urban DevelopmentWashington, OC 20410Dear Mr. Secretary:The American Dream for every family has at its core a comfortable home in a safe neighborhood, a home availableto buy or rent at a cost within the family budget, a home reasonably close to the wage earner's place of work.Unfortunately, too many American families today carmot fulfill their version of that dream because they carmot findaffordable housing.The cost of housing is being driven up by an increasingly expensive and time-consuming permit-approval process,by exclusionary zoning, and by well-intentioned laws aimed at protecting the environment and other featuTes ofmodem-day life. The result is that fewer and fewer young families can afford to buy or rent the home they want.These were among the concerns, Mr. Secretary, that you expressed when you established the Advisory Commissionon Regulatory Barriers to Affordable Housing. In your Charter, you asked this group of distinguished andexperienced Americans to explore the effect of the maze of Federal, State, and local laws, regulations, ordinances,codes, and innumerable other measures that act as barriers to the development of affordable housing in appropriateplaces. You asked the Commission to catalogue the barriers, identify the sources of those barriers, and proposesolutions that would help millions of American families to achieve their dream.Pursuant to your charge, the Commission has prepared a comprehensive Report that identifies regulatory barriers toaffordable housing and, just as important, proposes action to lower those barriers. Throughout the Report, theCommission expresses its belief that change is essential if the Nation is to meet its goals of a decent home andsuitable living environment for every American family.In closing, we wish to extend our deep gratitude to members of the Commission, who gave of their time and talentto fashion this Report. On their behalf, we have the honor to transmit to you, Mr. Secretary, pursuant to Section 12of the Charter, "Not In My Back Yard" : Removing Barriers to Affordable Housing, the Report of the AdvisoryCommission on Regulatory Barriers to Affordable Housing.Respectfully,Thomas H. Kean, Chainnan!2;: :: e;,:: /l

Marlldate to the CommissionWhen she visited the United States, the Russian human rights "activist"Yelena Bonner said to the American people: The people of the world do not wantwar, they want to own a house. They want to own a home. They want the decencyand dignity that goes along with their own home.The American dream is a universal dream. But all too often this dream ofownership, of decent and affordable housing, is being denied to fIrst-timehomebuyers and low- and moderate-income families. Government rules and redtape are regulating the dream out of existence. The challenge to this Commissionis to discover and to tell us how to remove those regulatory barriers.Jack KempSecretary of Housing and Urban DevelopmentFirst Meeting of the CommissionMay 31,1990

Commission MembersChairmanThomas H. KeanPresidentDrew UniversityVice ChairmanThomas Ludlow AshleyPresidentAssociation of Bank Holding CompaniesJerry E. AbramsonMayor of Louisville, KYKimi O. GrayChairperson, Board of DirectorsKenilworthlParkside Resident ManagementCorporationLarry P. ArnnPresidentClaremont Institute for the Study ofStatesmanship and Political PhilosophyRobert 1. BuchertPresidentAmerican Heritage Construction andDevelopment Corp.Stuart M. ButlerDirector, Domestic and Economic Policy StudiesThe Heritage FoundationBarbara M. Carey*Metro-Dade County CommissionerMiami, FLGale CincottaExecutive DirectorNational Training and Infonnation CenterJoanne M. CollinsMember of City CouncilKansas City , MOThomas B. CookDirector of Housing and Land UseBay Area CouncilSan Francisco, CAAnthony DownsSenior FellowThe Brookings InstitutionJ. Roger GluntPresidentGlunt Building Co., Inc .*Resigned October 5, 1990Greenlaw Grupe, Jf.Immediate Past President, Urban Land InstituteChainnan/CEOThe Grupe CompanyMaureen HigginsDirectorCalifornia State Department of Housing andCommunity DevelopmentJohn T. MaldonadoDirectorColorado Division of HousingRichard E. MandellVice PresidentThe Greater Construction Corp.James C. Miller IIIChainnanCitizens for a Sound Economy FoundationSue MyrickMayor of Charlotte, NCRobert B. O'Brien, Jf.Chainnan/CEOCarteret Bancorp, Inc.Paul M. WeyrichPresidentFree Congress Research and EducationFoundationRobert L. WoodsonPresidentNational Center for NeighborhoodEnterprise

Commission Staffu.s. Department of Housing and Urban DevelopmentJohn C. WeicherAssistant Secretary for Policy Development and ResearchJames W. StimpsonDeputy Assistant Secretary for ResearchResearch and Technical StaffMartin D. AbravanelTerrence L. ConnellDeborah J. DevineHarold R. HolzmanLester RubinSteven F. SmithDavid EngelOperations and Administrative StaffHeather A veilheKatherine L. O'LearyValerie F. DancyVanessa D. Void-TaylorLinda M. DeFilippoSenior AdvisorsAnthony M. Villane, Jr., DDS, Regional AdministratorLawrence L. Thompson, Executive AssistantAcknowledgmentsThe Commission wishes to thank the following individuals for their invaluable assistance andcontributions to its work: James E. Allen, Director, City of Louisville Department of Housing and UrbanDevelopment, Louisville, KY; William C. Myers, Director of State Policy, Free Congress Research andEducation Foundation, Washington, DC; and Margaret Howard, Chief of Staff, Office of the President,Drew University, Madison, NJ.

·"ContentsCo ntentsPreface . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1Executive Summary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3Part I. Regulatory Barriers and Affordable Housing . . . . . . . . 1-1Chapter 1. The Causes and Regulatory Consequences of the NIMBY Syndrome . . . . 1-1The Impact of NIMBY on Affordability . . . . . . . . . . . 1-2The Personal Basis of NIMB Y . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1-5Institutional Aspects of NIMBY . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1-7Checking the Effects of NIMBY and NIMTOO . . . . . . . . . . . . 1-9Chapter 2. Regulatory Barriers in the Suburbs . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2-1Growth Controls . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2-1Restrictive and Exclusionary Zoning . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2-5Excessive Subdivision Controls . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2-8Inequitable Fees on Development . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2-1 0Burdensome and Uncoordinated Approval and Permitting Systems . . . . . . . . . 2- 12Chapter 3. Regulatory Barriers in Cities . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3-1Restrictions on Urban Rehabilitation and Infill . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3- \Rent Control . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3-5Restrictions on Low-Cost Housing . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3-6Regulatory Restrictions on Certain Types of Housing . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3- 9Reinvestment in Older Urban Neighborhoods . .:. . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3-12Chapter 4. Environmental Protection Regulation and Affordable Housing . . . . . 4-1How Environmental Regulations Affect Housing Affordability . . . . . . . . . . . 4-1Wetlands and Affordable Housing . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4-3The Endangered Species Act and Its Effect on Housing . . . . . . . . . . . . 4-7Timber Production and Housing Affordability . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4-11Chapter 5. Other Factors Affecting Housing Affordability . . . . . . 5-1Poverty and Housing Affordability . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5-1The Housing Finance System . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5- 3The Tax System . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5-4Actions to Address Affordability Problems . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5-5The Affordability Problems of Low-Income Renters . . . . . . . . . . . . 5-7Conclusion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5-10

ContentsPart II. Commission Recommendations and Implementation Strategy . . II-lChapter 6. The Federal Role: Stimulating Regulatory Reform . . . . . 6-1Federal Initiatives . . . . . . 6-1Integrating Barrier Removal Into Housing Programs . . . . . . 6-2Recognizing Affordable Housing as a Major Federal Concern . . . . . . . 6-6Actively Working to Promote Affordable Housing . . 6-11Chapter 7. Increasing State Responsibility and Leadership . . . 7-1Rationale for Looking to the States . . . 7-1State Initiatives to Remove Local Regulatory Barriers . . . . . . . . 7-3What States Can Do, Are Doing, and Should Do . 7-5Chapter 8. Working Together: Efforts to Educate the Public, Build Coalitions, andConvince Local Policymakers to Dismantle Regulatory Barriers . . 8-1Common Misunderstandings About Regulatory Barriers . . . . . . . 8-2Raising Awareness and Educating the Public . 8-3The Need for Collective Action . . . . . 8-4The Role of Employers . . . 8-9Initiating Local Barrier-Removal Strategies . . . . . . 8-9Chapter 9. Strategy for Implementation . . . . . . . 9-1Dissemination of Commission Findings and Recommendations . . . . . 9-1Strategy for Implementing Federal Recommendations . . . 9-3Strategy for Implementing State and Local Recommendations . . . 9-5Appendices . . . . . . . . . . . . . . III-lA. Commission Hearings and Witnesses . . . A-IB. Biographies of Commissioners . . . . . . . B-1C. Charter of the Secretary's Advisory Commission onRegulatory Barriers to Affordable Housing . . . C-l

PrefacePrefaceThe Commission and theSecretary's MandateUnnecessary regulations at all levels of governmentstifle the ability of the private housing industry tomeet the increasing demand for affordable housingthroughout the country. To address this problem,President George Bush asked Secretary of Housingand Urban Development Jack Kemp to convene anAdvisory Commission that could identify regulatorybarriers to affordable housing and recommend howthese barriers could be removed. The Presidentobserved:[At] all levels of governments we have got to takea second look at some of the well-intendedhousing policies that actually decrease ourhousing supply. I'm talking about the excessiverules, regulations, and red tape that add unneces sarily to the cost of housing-by tens of thou sands of dollars---or that create perverse incen tives to allow existing housing to deteriorate .The negative impact of overregulation has causedconcern in the affordable housing debate for severaldecades. In the past 24 years, no fewer than 10federally sponsored commissions, studies, or taskforces have examined the problem, including thePresident's Commission on Housing in 1981-1982.These study groups have made many thoughtfulrecommendations, usually to little avail. In thedecade since 1981, the regulatory environment has ifanything become a greater deterrent to affordablehousing: regulatory barriers have become clearlymore complex, and apparently more prevalent.But opponents of regulatory barriers that inhibitaffordable housing have scored some successes.Perhaps the greatest success has been the increase inState activism, which has been a primary forcebehind code reform. Local building codes, widelyregarded in the past as barriers to the use of innova tive cost-saving technology, have in recent yearsbecome less of a problem as States more widelyadopt model codes and local governments moresystematically update their codes. Some States and anumber of localities have adopted policies to pro mote affordable housing, with impressive results.Encouraged by the successes and stimulated by thechallenge, this Commission eagerly accepted theinvitation of President Bush and Secretary Kemp. Attheir first meeting, the Commissioners voiced strongagreement with the sentiment of CommissionerRoger Glunt: "I don't come with an attitude that wecan't do anything. I have not been on a Federalcommission before-I have never failed at thisbefore-so I am going to try as hard as I can."The Commission represents a broad range of citizenswith extensive knowledge of and interest in thebuilding regulatory process and its impact uponhousing affordability. It includes builders, develop ers, and heads of nonprofit organizations who havedeveloped affordable housing units; governmentofficials who have promoted reform of housingregulations; appointed State and local officials withresponsibility for the regulatory process; recognizedpolicy experts who have analyzed the implicationsof regulation; and individuals representing interestsof low- and moderate-income families.

PrefaceGoal and ObjectiveThe Commission's goal has been to assess compre hensively prevailing Federal, State, and localregulations governing construction and rehabilita tion, and to recommend ways to reduce the barriersto affordable housing these regulations may raise.The year-long review included an examination ofFederal housing and environmental regulations andState and local regulations regarding growth con trols, zoning, permitting, and building codes. Mind ful of previous efforts, the Commission establishedearly the objective of developing implementationstrategies for its recommendations. With thesestrategies as part of this Report, the Commissionbelieves its recommendations are more likely to beadopted, and more likely to be effective.To guide its deliberations, the Commission devel oped a definition of the problem of affordablehousing. It concluded that, most urgently, there isnot enough "affordable housing" when a low- ormoderate-income family cannot afford to rent or buya decent-quality dwelling without spending morethan 30 percent of its income on shelter, so muchthat it cannot afford other necessities of life. Withrespect to renters, the Commission is particularly2concerned about those. with incomes below 50percent of the area median income. In other cases, italso means that a moderate-income family cannotafford to buy a modest home of its own because itcannot come up with the downpayment, or makemonthly mortgage payments, without spending morethan 30 percent of its income on housing.The problem of housing affordability touches manyAmericans: renters who lack savings to afford adownpayment on a house, parents whose childrencannot afford to live nearby when they start theirown families, low-income households who spendhalf of their income on housing, and persons whocommute long distances because they cannot affordto live near where they work.The Commission recognizes the influence of manyfactors and phenomena on housing affordability,ranging from macroeconomic policy to technologi cal change. The Commission's charter specifies,however, that it should focus on regulatory barriersas a particularly important and growing cause of theshortage of affordable housing. The Commissionbelieves that a successful effort to reduce regulatorybarriers will benefit many American families,especially young households and low-incomefamilies, and will substantially ameliorate thenational housing affordability problem.

".Ex ecutiveExecutive SummarySummaryillions of Americans are being priced outof buying or renting the kind of housingthey otherwise could afford were it not fora web of government regulations. Forthem, America-the land of opportunity-has be come the land of a frustrating and often unrewardedsearch for an affordable home:M Middle-income workers, such as policeofficers, firefighters, teachers, and other vitalworkers, often live many miles from thecommunities they serve, because they cannotfind affordable housing there.II Workers who are forced to live far from theirjobs commute long distances by car, whichclogs roads and highways, contributes to airpollution, and results in significant losses inproductivity . Low-income and minority persons have anespecially hard time finding suitable housing.II Elderly people cannot find small apartments tolive near their children; young married couplescannot find housing in the community wherethey grew up.These people are caught in the affordability squeeze.Contributing to that squeeze is a maze of Federal,State, and local codes, processes, and controls. Theseare the regulatory barriers that--often but not alwaysintending to do so-delay and drive up the cost ofnew construction and rehabilitation. These regulatorybarriers may even prohibit outright such seeminglyiJUloCUOUS matters as a household converting sparerooms into an accessory apartment.Govenunent action is essential to any strategy toassist low- and moderate-income families in meetingtheir housing needs. But government action is also amajor contributing factor in denying housing oppor tunities, raising costs, and restricting supply. Exclu sionary, discriminatory, and unnecessary governmentregulations at all levels substantially restrict theability of the private housing market to meet thedemand for affordable housing, and also limit theefficacy of government housing assistance and sub sidy programs.In community after community across the country,local governments employ zoning and subdivisionordinances, building codes, and permitting proce dures to prevent development of affordable housing."Not In My Back Yard"-the NIMBY syndrome has become the rallying cry for current residents ofthese communities. They fear that affordable housingwill result in lower land values, more congestedstreets, and a rising need for new infrastructure suchas schools.What does it mean if there is not enough "affordablehousing"? Most urgently, it means that a low- ormoderate-income family cannot afford to rent or buya decent-quality dwelling without spending morethan 30 percent of its income on shelter, so much thatit cannot afford other necessities of life.) With re spect to renters, the Commission is particularlyconcerned about those with incomes below 50 per cent of the area median income. In other cases, it alsomeans that a moderate-income family cannot affordto buy a modest home of its own because it caJUlotcome up with the downpayment, or make monthlymortgage payments, without spending more than 30percent of its income on housing.Concern about the effects of regulation on housingaffordability is not new. Other commissions over thepast two decades have examined the causes, framedI For purposes of this Repon, the Commission believes that ahousing affordability problem exists when a household earning100 percent or less of area median income cannot afford to rentor buy safe and sanitary housing in the market without spendingmore than 30 percent of its income.3

Executive Summarythe issues, and recommended solutions concerningthe impact of regulation on housing prices. The factthat the problem remains today should not detercontinued efforts to resolve it. This Commission hastherefore considered both what should be done andhow to make sure that it is done.Many forces in addition to regulatory barriers affectthe problem of affordability of housing. Certainlysome aspects of both the housing finance system andthe tax structure seem to inhibit the availability ofaffordable housing. For very low-income house holds, the root problem is poverty. But even for verylow-income households, regulatory barriers makematters worse.Those other forces are beyond the purview of thisCommission's study. What is within its purview isthe effect of regulatory barriers on the cost of hous ing, and that is substantial. The Commission hasseen evidence that an increase of 20 to 35 percent inhousing prices attributable to excessive regulation isnot uncommon in the areas of the country that aremost severely affected.The Basic ProblemWhether the search for housing takes place in rap idly growing suburban areas or older central cities,the basic problem is the same: because of excessiveand unnecessary government regulation, housingcosts are too often higher than they should and couldbe. Yet the specific government regulations that addto costs in suburban and high-growth areas tend todiffer from those adding to costs in central cities.Regulatory Barriers in theSuburbsIn the Nation's suburbs, the landscape of theaffordability problem reveals a variety of topicalfeatures. Exclusionary zoning, reflecting the perva sive NIMBY syndrome, is one of the most prom i 4,nent. Some suburban areas, intent on preservingtheir aesthetic and socioeconomic exclusivity, erectimpediments such as zoning for very large lots todiscourage all but the few privileged householdswho can afford them. Some exclude, or minimallyprovide for, multifamily housing, commonly ac knowledged to be the most affordable form ofhousing.In theory a way of separating "incompatible" landuses to protect health and safety, zoning has becomea device for screening new development to ensurethat it does not depress community property values.As a result, some suburban communities, consistingmainly of single-family homes on lots of one acre ormore, end up as homogeneous enclaves wherehouseholds such as schoolteachers, firefighters,young families, and the elderly on fixed incomes areall regulated out.Suburban gatekeepers also invoke gold-plated subdi vision controls to make sure that the physical anddesign characteristics of their communities meetvery demanding standards. Many of these communi ties are requiring that developeTs provide offsiteamenities such as parks, libraries, or recreationalfacilities that can add substantially to the housingcosts of new homebuyers.

Executive SummaryHere . in Mercer County, a majorsubdivision would receive . ll differ ent reviews from 9 different agencies.Seven of those reviews concern them selves with the adequacy of storm -drainage. Jet fighter planes and moonrockets get by with triple redundantcontrol systems. We need seven gov ernment agencies to look at whetherthe storm drainage will drain. It is animportant concern, but it is probablynot that important.William Connolly, DirectorDivision of Housing andDevelopmentNew jersey Department ofCommunity AffairsCommunities are increasingly charging large fees todevelopers who seek the privilege of building hous ing in them. These fees may bear little resemblanceto the actual cost of providing services and facilitiesthat new subdivisions require. Although fee sched ules are often driven by fiscal concerns, they have aregressive effect. Fees are generally fixed regardlessof how much they affect the cost of a new home.Thus, households that can only afford less expensivehouses end up paying a higher proportion of thesales price to cover the cost of fees.Slow and overly burdensome permitting is anotherregu1atory obstacle. The original rationale for estab lishing permitting and approval processes isunassailable: to ensure that construction meetsestablished standards related to health, safety, andother important public concerns. But, in manyjurisdictions, the process involves multiple, time consuming steps that add unnecessarily to housingcosts. Delays of 2 to 3 years are not uncommon.The affordability landscape comes most sharply intofocus in areas that are experiencing rapid growth.These are the places that attract households seekingopportunities, and the places where growth-control-ling regulations can add considerably to the cost ofhousing. Local residents--concerned about roadcongestion, overburdened sewer and water systems,overcrowded schools, and strained city budgets have many ways to limit growth. Households that donot want to forgo the job opportunities in growingareas must often travel far afield to find affordablehousing.A look at some cost data can be very sobering. Landdevelopers in Central Florida, a boom area underintense development pressure, must add a 15,000surcharge to the price of a 55,000 house to coverthe costs of excessive regulation. A 55,000 housebecomes a 70,000 house. In Southern California,the cost of fees alone has contributed 20,000 to theprice of many new homes, and fees of 30,000 ormore are not rare. In New Jersey, developers reportthat excessive regulation is adding 25 to 35 percentto the cost of a new house. It is clear that the costs ofregulation in suburban and high-growth areas arecausing large numbers of households to forgo theirdreams of homeownership or to make difficulttradeoffs involving very long commutes.In Moreno Valley, California, themorning rush hour begins a little after4:00 a.m. as thousands of sleepycommuters-mostly men-stumbleinto their cars to begin their 70-mUe - .westward trek to the job centers ofOrange County. If they're lucky,they'll slip throug the Highway 91 Interstate 15 bottleneck in nearbyCorona before 5:00, when the morn ing traffic jam typically begins. Thatway, they'll be in Orange County by6:00,able to catch an extra hoor ofsleep in their cars before the.workdaybegins.William ·Fultoo"The Long Commute'"PlanningJuly 1 2(J .5

Executive SummaryRegulatory Barriers in CitiesAny government regulation that adds to the cost ofurban housing is especially significant because ofthe concentration of low-income households incentral cities. Unlike suburban areas where large scale new subdivision development is taking place,the regulatory problems in cities involve either therehabilitation of older properties or new infill con struction to provide afforaable housing for familiesof limited means. Central-city reinvestment has beenfurther co

The American dream is a universal dream. But all too often this dream of ownership, of decent and affordable housing, is being denied to fIrst-time . Claremont Institute for the Study of . Statesmanship and Political Philosophy . Robert 1. Buchert . Research and Technical Staff . Martin D. Abravanel Harold R. Holzman