Transcription

PRIVATE INVESTMENTS,PUBLIC HARMHow the Opacity of the Massive U.S. PrivateInvestment Industry Fuels Corruption andThreatens National SecurityDecember 2021

Authors: Erica Hanichak, FACT Coalition Lakshmi Kumar, Global Financial Integrity Gary Kalman, Transparency International U.S. OfficeReviewers: John Keenan, American Federation of State, County, and MunicipalEmployees (AFSCME) Ian Gary, FACT Coalition Ryan Gurule, FACT Coalition Elise Bean, Former Staff Director and Chief Counsel, U.S. SenatePermanent Subcommittee on Investigations Josh Rudolph, The German Marshall Fund’s Alliance for SecuringDemocracy Kelly McDermott, Never Again Coalition Scott Greytak, Transparency International U.S. Office Covington & Burling, LLPThe findings and analysis in this report represent the views of itsauthors, and not necessarily those of any participating reviewer ororganization.Every effort has been made to verify the accuracy of the informationcontained in this report. All information was believed to be correct as ofNovember 2021. Nevertheless, the authors cannot accept responsibilityfor the consequences of its use for other purposes or in other contexts. 2021. This report is covered by the Creative Commons “AttributionNo Derivs-NonCommercial” license (see http://creativecommons.org).It may be reproduced in its entirety as long as Global Financial Integrity,Transparency International, and the FACT Coalition are credited, alink to the organizations’ web pages are provided, and no charge isimposed. The report may not be reproduced in part or in altered form,or if a fee is charged, without permission from Global Financial Integrity,Transparency International, and the FACT Coalition. Please let theorganizations know if you reprint.”

ABOUT USFinancial Accountabilityand CorporateTransparency (FACT)CoalitionThe Financial Accountabilityand Corporate Transparency(FACT) Coalition is a non-partisanalliance of more than 100 state,national, and internationalorganizations working toward afair tax system that addresses thechallenges of a global economyand promoting policies to combatthe harmful impacts of corruptfinancial practices.Global FinancialIntegrityTransparencyInternational U.S. OfficeGlobal Financial Integrity (GFI) isa Washington, D.C.-based thinktank focused on illicit financialflows, corruption, illicit tradeand money laundering. Throughhigh-caliber analyses, fact-basedadvocacy to promote beneficialownership and a cloud-baseddatabase to curtail trade fraud,GFI aims to address the harmsinflicted by trade misinvoicing,transnational crime, tax evasionand kleptocracy. By working withpartners to increase transparencyin the global financial systemand promote Trade Integrity, GFIseeks to create a safer and moreequitable world.Transparency International is aglobal movement with one vision:a world in which government,business, civil society and thedaily lives of people are freeof corruption. With more than100 chapters worldwide andan international secretariat inBerlin, we are leading the fightagainst corruption to turn thisvision into reality. The U.S.office focuses on stemming theharms caused by illicit finance,strengthening political integrity,and promoting a positive U.S.role in global anti-corruptioninitiatives. Through a combinationof research, advocacy, and policy,we engage with stakeholders toincrease public understanding ofcorruption and hold institutionsand individuals accountable.

TABLE OFCONTENTS6EXECUTIVE SUMMARY22 The European Union and UK Impose AMLRequirements on Investment FundsINTRODUCTION22 Case Studies8MAPPING THE PROBLEM321415 Assessing Demand for Financial SecrecyInstruments with Long-Term Horizons18UNDERSTANDING THECURRENT FRAMEWORK19 Current U.S. Customer Due DiligenceObligations for Financial InstitutionsExclude Private Investment Companies andInvestment Advisers20 Historical Efforts to create AML/CFTobligations for Investment Companies andAdvisersFINDING THE SOLUTION32 An AML Rule For Investment Advisers andInvestment Companies is Urgently Neededand can be Created Without Any New Actionfrom Congress34 Recommendations36CONCLUSION

ABBREVIATEDKEY TERMSAML/CFTAnti-Money Laundering/Combatting the Financingof TerrorismBSABank Secrecy ActCDDCustomer Due DiligenceCTACorporate Transparency ActFATFFinancial Action Task ForceFinCENFinancial Crimes Enforcement NetworkKYCKnow Your CustomerSARSuspicious Activity ReportSECSecurities and Exchange CommissionVCFVenture Capital Firm

EXECUTIVESUMMARYA growing body of evidencesuggests that this gap – theabsence of requirementsthat investment fundsand investment advisersestablish anti-moneylaundering programsand conduct reviews tounderstand with whomthey are doing business – isa significant vulnerabilitythat negatively impactsU.S. national securityand the lives of ordinaryAmericans.The Pandora Papers exposéagain reveals how financialsecrecy in the United States hasmade the country a favoreddestination for the world’s eliteto hide illicit funds. The U.S.private investment industry,unfortunately, offers a perfectconfluence of factors that make itan ideal place to hide and launderthe proceeds of corrupt andcriminal activity. It is large. The U.S. marketalone holds more than US 11trillion dollars in assets. It is opaque. Private funds,which target high-net worthinvestors, do not have thesame reporting requirementsas public equity and retailfunds marketed for ordinaryinvestors. It is complex. In the UnitedStates, there are nearly13,000 investment adviserswith little to no anti-moneylaundering due diligenceresponsibilities.The U.S. has adopted andimplemented a series of rulesto detect and prevent illicitfunds from entering its financialsystem. The Bank Secrecy Act(BSA), passed in 1970, establishedan anti-money laundering6(AML) framework. Subsequentlegislative updates andregulations built out a risk-basedapproach to AML reporting in theU.S. across 25 types of financialinstitutions ranging from banks,broker-dealers, mutual funds,credit unions, casinos, pawnshops, and others. The expansionof the U.S. rules largely followinternational standards. Twonotable exceptions are 1) thelack of regulation of investmentadvisers – that is, individualsor firms in the compensatedbusiness of providing adviceabout investing in securities;and 2) unregistered investmentcompanies such as hedge funds,private equity, venture capitalfunds, and real estate investmenttrusts, and family offices.A growing body of evidencesuggests that this gap – theabsence of requirements thatinvestment funds and investmentadvisers establish anti-moneylaundering programs and conductreviews to understand withwhom they are doing business –is a significant vulnerability thatnegatively impacts U.S. nationalsecurity and the lives of ordinaryAmericans.

PRIVATE INVESTMENTS, PUBLIC HARMAs detailed in this report, a fewexamples demonstrate the risks: Russian and Chineseinterests have sought accessto sensitive U.S. technologyand innovation throughprivate investment vehicles. A cryptocurrency scheme runthrough private equity wasamong the largest financialscams in history. A lack of disclosure in privateequity obscured the majoritystake owned by a Russianoligarch in a U.S. votingmanagement firm activein Maryland, calling intoquestion election security.A leaked FBI intelligencebulletin included examples ofillicit financial schemes usingpooled investment vehiclesinvolving Mexican drugcartels, Russian organizedcrime, and U.S. sanctionedcountries.In 2002, 2003, and 2015, the U.S.Treasury Department proposedrules to close the gap and requirethe private investment industryto perform due diligence onpotential investors. Unfortunately,the proposed rules were neverfinalized and the vulnerability inour financial system remains.The FACT Coalition, GlobalFinancial Integrity, and theTransparency InternationalU.S. Office recommend that theU.S. Treasury Department updateand finalize an AML rule coveringboth investment advisers andinvestment companies to addresssignificant threats to America’sfinancial system, national security,and citizens. The rule shouldrequire (1) establishing a riskbased anti-money laundering andcounter terrorist financing (AML/CTF) program; (2) identificationof the real, “beneficial” owners oflegal entities that open accounts;(3) assessments of those ownersand their transactions to identifymoney laundering risk; (4)the filing of suspicious activityreports with the Financial CrimesEnforcement Network (FinCEN)when sufficient risk is identified;and (5) the ongoing monitoringof accounts with a higherrisk profile.A strong rule that wouldbolster national security andmitigate threats to America’sfinancial system should coverthe full range of unregisteredinvestment companies andinvestment advisers, to avoidinadvertently creating loopholesripe for exploitation. FinCENshould design the rule toinstitute affirmative anti-moneylaundering obligations for thefollowing categories of advisers:1. Advisers currently registeredwith the U.S. Securities andExchange Commission (SEC);2. Advisers working solely withhedge funds, private equity,venture capital funds, ruralbusiness investment companies,family offices, or any other typeof private fund; and3. Advisers working as foreignprivate advisers.The Biden administration hasrightfully designated the fightagainst corruption as a nationalsecurity priority and as a corepillar of the forthcoming Summitfor Democracy. Committing tofinalize a rule on unregisteredinvestment companies and thefull range of investment adviserswould provide critical safeguardsto close money launderingloopholes and protect theintegrity of the U.S. and globalfinancial systems.7

INTRODUCTIONAs the world’s largest economy, the United States is a prime targetfor financial investment using legitimate and illegitimate resourcesalike. A recent paper by Global Financial Integrity found thefollowing: The amount of illicit non-tax evading money generatedand laundered annually in the US is estimated at 300 billion. Whenmoney laundered from tax evasion, coupled with illicit funds thatenter the US financial system from outside the country are added,that figure could approach as much as 1 trillion.1D8

PRIVATE INVESTMENTS, PUBLIC HARMIn recent years, significantattention has been generatedon the use of anonymouscompanies, art, antiquities, andtrade-based money launderingto facilitate illicit money in andout of the United States. Theattention and advocacy aroundthese issues culminated inthe passage of the CorporateTransparency Act (CTA) in 2021.This landmark law requiresthe creation of a beneficialownership directory and an AML/CFT rule for antiquities dealersalongside a requirement that theTreasury Department undertakestudies into the risks of moneylaundering through art andtrade-based money laundering.One area of risk that has beenconspicuously absent in all ofthese efforts to strengthen theU.S. financial system againstabuse are measures to createaccountability within the U.S.private investment industryincluding hedge funds, privateequity, venture capital firms, andfamily offices.These vulnerabilities in the U.S.financial system from the privateinvestment sector are far fromhypothetical and encompassmore than one-off examples. InJuly 2020, a leaked FBI intelligencebulletin revealed that the FBIbelieved with ‘’high-confidence”that the US 11 trillion privateinvestment fund industry wasbeing used to launder money.2The assessment concluded thathedge funds, private equityfunds, and other types of privateplacements of funds were beingutilized to move illicit proceeds,3and referred back to a 2019FBI report where it likewiseconcluded criminal actors were“very likely” to launder proceedsfrom fraud schemes through“fraudulent hedge funds andprivate equity firms.”4So why are criminal and corruptactors turning to privateinvestment vehicles to legitimizetheir illicit funds? Choosing howto obscure one’s illicit fundsinvolves a number of factors,including, but not limited to, theopacity of transactions and thesize of the market. The privateinvestment sector in the UnitedStates, unfortunately, offers aperfect confluence of favorablefactors that make it an ideal placeto hide and launder the proceedsof corrupt and criminal activity.One area of risk thathas been conspicuouslyabsent in all of theseefforts to strengthenthe U.S. financialsystem against abuseare measures to createaccountability within theU.S. private investmentindustry including hedgefunds, private equity,venture capital firms, andfamily offices.9

First, the U.S. privateinvestment market isopaque. While retail tradingplatforms have several publicreporting requirements, privateinvestments have almost none.U.S. securities laws requireprivate equity firms to ensurethat the clients they acceptare “qualified purchasers” or“accredited investors,”but do not require them todisclose – to the public or thegovernment – the identity ofthose clients. While investmentfirms must ensure their clientshave an ability to weather a lossand assume investment risk, theycurrently do not have to screenthe clients’ funds or businessactivities to avoid investing illicitfunds. In addition, accreditedWhat does an investment advisor do?An investment adviser is a firm or individual that offersguidance on, or otherwise manages, the investmentdecisions of their clients.While an investment adviser may direct decision’s aboutclients’ portfolio with their consent, the adviser may ormay not personally execute the purchase, sale, or tradeon behalf of their client. They sometimes work through athird-party broker-dealer to get the job done.It is other instances, in which the investment adviseroperates independently outside the scope of anti-moneylaundering safeguards, that pose the most risk.10investors can be either naturalpersons or legal entities5 whichcan further add to the opacity ofan investor’s identity.Furthermore, public investmentfunds almost always employregistered investment brokersto identify clients and executetrades on the clients’ behalf.These brokers are required bylaw to know with whom theyare doing business, as theyhave what is called “know yourcustomer” (KYC) due diligenceresponsibilities.6 That means thatU.S. brokers have an obligationto check that any prospectiveclient, either an individual or anentity, is not attempting to movedirty money into the U.S. financialsystem. In contrast, privateinvestment vehicles do not alwaysuse registered brokers withAML obligations. While no U.S.business is allowed to directlyengage with anyone on an officialU.S. sanctions list, unlike someother financial service providers– banks for instance – private

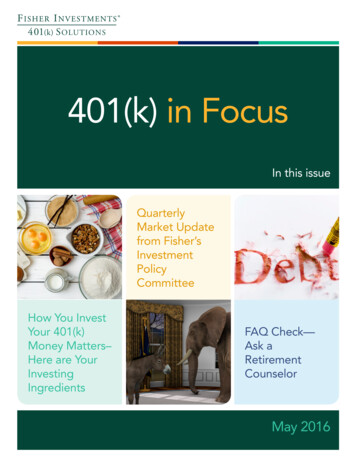

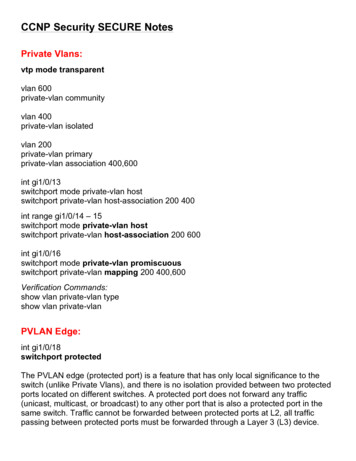

PRIVATE INVESTMENTS, PUBLIC HARMGDPS FOR 2020U.S. PRIVATEINVESTMENT 2.7 T 11.0 TCHINA 3.8 T 14.7 TUNITEDSTATES 5.0 T 20.9 TU.S. private investment market would be 3rd largest economyin the world.JAPANGERMANYU.K.21Trillions (USD)Private equity, hedgefunds, and venture capitalhad approximately US 11trillion in assets in 2020,and the private investmentmarket is growing rapidly.0*Source: D?most recent value desc trueinvestment vehicles are notrequired to perform even a basiccheck to determine if an agentor entity requesting servicesis actually a front for a corruptor criminal actor. Nor are theyrequired to report suspiciousactivity to authorities, limiting lawenforcement’s ability to detect orprevent illicit transactions.Second, the U.S. privateinvestment sector is verylarge. Overall, the total equitymarket – public and privateinvestments – in the United Statesis larger than the economy itself.With more than US 59 trillionin assets under management,the U.S. market is at leastfour times the size of the nextlargest market.7 While privateinvestment makes up only aportion of the total market, it isstill a very large market by anymetric. Private equity, hedgefunds, and venture capital hadapproximately US 11 trillion inassets in 2020, and the privateinvestment market is growingrapidly.8 Investments in privateequity have “grown more thansevenfold since 2002, twice asfast as global public equity.”9Venture capital firms, a formof private equity, grew by 13percent per year in that sameperiod including in 2018, whichranked as the third biggest yearfor raising capital on record.10Experts project private equity willdouble its current portfolios toUS 9 trillion by 2025, and hedgefunds will grow to a little morethan US 4 trillion.11 The U.S.commercial banks, which do haveKYC responsibilities, now holdapproximately US 22.5 trillion indeposits.12 The private investmentmarket is quickly growing to anequivalent size.Finally, while there are almost5,000 commercial banks inthe United States, all with KYCobligations, almost 13,000 hedgefunds, private equity, venturecapital firms, and family officesare operational without similarrequirements.1311

MONEY LAUNDERING IN A PRIVATE INVESTMENT TRANSACTIONMr. Bad is a corrupt official who stole millions and is sanctioned bythe U.S. government.SCENARIO 1: U.S. BANKMr. Bad takes his stolen money to a U.S. bank. The bank does a “knowyour customer” check and turns him down.SCENARIO 2: ANONYMOUS COMPANYMr. Bad creates an anonymous company and moves his stolen moneyinto the company. The company goes to a U.S. bank. The bank does a“know your customer” check and turns him down.SCENARIO 3: OFFSHOREMr. Bad registers his anonymous company offshore and tries to investthe money through a U.S. investment broker in public funds. The brokerdoes a “know you customer” check and turns him down.PRIVATE INVESTMENT TRANSACTIONMr. Bad’s anonymous company uses the offshore account to invest withan investment adviser in private funds, who may only check to see if thereare enough funds in the account. Then, they can legally say yes, let’s dobusiness!12

PRIVATE INVESTMENTS, PUBLIC HARMThe Biden administration’sexpansive anti-corruptionplatform has created anenvironment ripe for actionto close gaps in the U.S.AML framework. In its June2021 national security studymemorandum, the White Houseelevated anti-corruption as a corenational security interest, callingcorruption a threat to “UnitedStates national security, economicequity, global anti-povertyand development efforts, anddemocracy itself” and proposing,as a solution, U.S. policiesaround “effectively preventingand countering corruption anddemonstrating the advantagesof transparent and accountablegovernance.”14 A senior WhiteHouse official explained, “we’relooking to make significantsystemic changes to theregulatory structure that governsillicit finance.”15 Safeguardingthe U.S. investment market fromabuse by corrupt regimes, U.S.adversaries, and criminals helpsprotect Americans and Americannational security interests whileaiding U.S. partners in low- andmiddle-income countries tocombat illicit financial flows thatundermine good governanceand rob them of much-neededresources.Safeguarding the U.S.investment market fromabuse by corrupt regimes,U.S. adversaries, andcriminals helps protectAmericans and Americannational security interestswhile aiding U.S. partnersin low- and middle-incomecountries to combatillicit financial flowsthat undermine goodgovernance and rob themof much-needed resources.13

MAPPINGTHE PROBLEM14

PRIVATE INVESTMENTS, PUBLIC HARMAssessing Demandfor Financial SecrecyInstruments with LongTerm HorizonsThe first mention of a moneylaundering operation oftenconjures up the mental image ofa seedy, all-cash business on theedge of town. Yet methodologiesto launder illicit financial flowsare plentiful, and many have keptpace with a modern, globalizedeconomy. The benefits to thecriminal and corrupt are twofold: they discover increasinglysophisticated ways to evadelaw enforcement by diversifyingtheir holdings, while theysimultaneously maximize returnson ill-gotten gains.Established criminal networkslike Italy’s ‘Ndrangheta mafiahave shown the necessarypatience to leverage financialmarkets for their fraudulentschemes. For instance, between2015 and 2019, the powerfulmafia organization reportedlyattracted approximately US 1.6billion in legitimate internationalinvestment – from hedge funds,family offices, pension funds,and other market participants,including one of Europe’slargest private banks – by sellingprivate bonds backed by frontcompanies embedded in Italy’shealth sector.16 The assets werereportedly sold through aninstrument created by CFE, aSwiss investment bank, whichclaimed no knowledge of thecriminal nature of the assets.17The benefits to thecriminal and corruptare two-fold: theydiscover increasinglysophisticated ways toevade law enforcementby diversifying theirholdings, while theysimultaneously maximizereturns on ill-gotten gains.Likewise, foreign corruptionpresents a threat to the integrityof U.S. investment channels.Many authoritarians haveinvestment horizons that matchtheir decades-long rule. As such,they engage in the equivalentof illicit estate planning: toconsolidate power in-country, tokeep their wealth out of reach ofpolitical opponents by moving itto rule-of-law jurisdictions, andultimately, to pass on their wealthto their children.15

For both the criminaland the corrupt, moneylaundering is not justabout short-term gains.16The dictatorial demand for longterm investments moves moneythrough a multitude of financialvehicles. For instance, look toreal estate. Teodoro Obiang –president of oil-rich EquatorialGuinea and one of the world’slongest serving dictators – hasdepleted the country’s coffers andmade Equatorial Guinea one ofAfrica’s lowest per-capita incomecountries.18 He has reportedlyused the stolen wealth tocement his financial and politicaldominance, make extravagantpurchases abroad (including aUS 2.6 million mansion a fewmiles from the U.S. Capitol),and tee up rule for his sons.19According to a settlement withthe Department of Justice,Teodorin Obiang, one of two sonsand the current vice president,reportedly used shell companiesas conduits for embezzled moneyto buy real estate in Malibu,California, Michael Jacksonmemorabilia, and a US 35 millionGulfstream jet. 20,21Trusts offer another investmentvehicle. Ferdinand Marcos ruledthe Philippines as president for21 years, and during that time,was believed to have stolenUS 10 billion while in office.22 Yet,during this 20-year period, hisofficial annual salary never roseabove US 13,500.23 Though manyof the Marcos family accountswere frozen after his governmentfinally fell in the 1980s, hundredsof millions of dollars remainedunrecovered. Two decades later,a whistleblower stated that“lawyers for KPMG (then knownas Fides, a subsidiary of CreditSuisse) moved the 400 million inMarcos funds to a Liechtensteintrust, Limag Management undVerwaltungs AG” where, left toaccrue interest in the interveningyears, its value was estimated tohave doubled.24 KPMG has deniedthe whistleblower’s accusations.The availability, secrecy, and longinvestment horizon of a trustprovide parallels to the operationof many U.S. private investmentfunds.

PRIVATE INVESTMENTS, PUBLIC HARMOther powerful figures injurisdictions plagued bycorruption likewise turn to longterm investments, includingby recruiting family offices andother gatekeepers to managetheir wealth. Jahangir Hajiyev,former chair of the biggest bankin Azerbaijan, earned a salaryof US 70,650 in 2008. 25 YetJahangir and his wife Zamira –who, according to Bloomberg,“earned no significant incomeherself” – spent millions of dollarsin the UK purchasing a US 14.3million townhouse in Londonand a Gulfstream jet for US 42.5million.26 Zamira, in a weekalone, reportedly spent nearlya million dollars at the Harrodsdepartment store in London.27According to a National CrimeAgency investigation, the couplewas allegedly able to hide andspend all this money throughthe assistance of a network ofgatekeepers including the globaltrust administration firm TridentTrust, which has operations inthe U.S., and a multi-family officeWerner Capital, based in London,that helped set up entities to holdthe couple’s various assets.28 It’sunclear what questions eitherfirm asked the couple aboutthe source of their wealth whentaking them on as clients.29Perhaps surprisingly, even thesetraditionally long-term horizoninvestments are not safe fromshort-term exploitation for thepurposes of financial secrecy.There is no better example thanthe 1MDB scandal, a global caseof corruption in which privateequity played a prominent rolein the theft of billions fromthe country’s developmentfund by the former PrimeMinister of Malaysia.30 A 2016U.S. Department of Justice civilforfeiture complaint regardingthe 1MDB scandal claimedthat hundreds of millions ofdollars from the developmentfund meant for a bond offeringwere layered through privateinvestment funds and thenpocketed by the perpetrators ofthe fraud. In one such example,over the course of one weekin May 2013, an arm of thedevelopment bank, 1MDBGlobal, purportedly transferreda total of US 1.59 billion from itsSwiss bank account to accountsbelonging to three differentoverseas investment funds inthe British Virgin Islands and inCuraçao.31 The funds were passedback and forth through multipleaccounts held in the names ofdifferent legal entities but all withthe same beneficial owner. In arelated case, it was determinedthat the crisscross movementof funds had no legitimatecommercial purpose and wasdesigned to “obscure the nature,source, location, ownership and/or control of the funds.”32 Clearly,private investment funds areripe for exploitation, includingas short-term and long-terminvestment vehicles used todisguise and conceal the origin ofillicit funds.The 1MDB case, in particular,illustrates an additional point:the lack of AML programs anddisclosure requirements in theU.S. private investment industryheighten risks among advisersand companies located in theUnited States as well as amongadvisers located outside the U.S.seeking to access U.S. markets.Non-U.S. advisers are boundto view the U.S. financial sectoras an attractive avenue to hideillicit funds, given the lack of AMLcontrols and opacity of the U.S.private investment industry.Increasing the risk to the U.S.financial system is the low level ofAML enforcement activity outsideof the United States, whetherdue to limited resources, a weakregulatory climate, or a lack ofpolitical will to tackle moneylaundering. These non-U.S.deficiencies can be exploited tocreate added opacity around theidentity of non-U.S. individualsand entities seeking to exploit theU.S. financial system.For both the criminal and thecorrupt, money laundering is notjust about short-term gains. Asthe above examples from acrossthe globe illustrate, criminals andkleptocrats are, in fact, interestedin financial instruments with alonger horizon, an acceptablereturn on investment, and theability to diversify their holdingsand conceal their moneylaundering tactics. For those withthe means, the long horizon, highyield, and opacity of multi-yearinvestments like those offered byhedge funds, private equity, andventure capital firms make themattractive conduits for moneylaundering.17

UNDERSTANDINGTHE CURRENTFRAMEWORKThe U.S. anti-money laundering regime – enshrined in BankSecrecy Act (BSA) regulations – has built out a risk-based approachto AML reporting across 25 types of financial institutions includingbanks, mutual funds, credit unions, casinos, pawn shops, andothers.33 The list includes broker-dealers who, like investmentadvisers, can execute trades in securities on behalf of clients.FinCEN’s CDD rule was animportant step towardmeeting internationalstandards, but it failedto include a strongdefinition of beneficialowner, and it failed toencompass all of theentities specified in FATF’sdefinition of “financialinstitution,” such asprivate investment funds.Unlike broker-dealers, however,investment advisers are notcurrently required to maintainanti-money laundering/combatting the financing ofterrorism (AML/CFT) programsunder the BSA. Nor are severaltypes of “investment companies,”which are explicitly exemptedfrom that requirement.34 WhileFinCEN has made multipleattempts to create anti-moneylaundering obligations forinvestment advisers and certaininvestment companies, the U.S.has failed to finish the workand so remains an outlier asthe United Kingdom and othercountries with similar financialsystems in the European Unionhave applied their anti-moneylaundering requirements to theprivate investment sector.This section examines U.S. effortsat strengthening customer duediligence (CDD) requirements forfinancial institutions, previous18attempts at creating AML/CFTrequirements for investmentadvisers and investmentcompanies, and current regulatorypractice among U.S. allies.Current U.S. CustomerDue DiligenceObligations for FinancialInstitutions ExcludePrivate InvestmentCompanies andInvestment AdvisersThe BSA has been regularlyamended over the course ofits 50-year history to meetmodern challenges. The FinancialAction Task Force (FATF), theinternational standard-settingorganization for anti-moneylaundering and combatingterrorist financing, describedthe U.S. framework in its mostrecent evaluation in 2016 as “welldeveloped,” coordinated acrossgovernment agencies, and rooted

PRIVATE INVESTMENTS, PUBLIC HARMin a sophisticated understandingof money laundering and terrorfinancing risks.35Yet the same 2016 FATFevaluation highlighted a majorU.S. deficit. The deficit wasthat, in the United States, lawenforcement and other essentialparties had no way of learning theidentity of the true, “beneficial”owner of legal entities formedin the 50 U.S. states. In January2021, Congress took an importantstep towards curing that deficitby enacting the CorporateTransparency Act, which will,when implemented, requirecorporations, limited liabilitycompanies, and other similarentities to report their beneficialowners to a secure database atFinCEN.A related problem was that,although as of 2001 the BSArequired financial institutionsto establish AML programs,BSA

GFI aims to address the harms inflicted by trade misinvoicing, transnational crime, tax evasion and kleptocracy. By working with partners to increase transparency in the global financial system and promote Trade Integrity, GFI seeks to create a safer and more equitable world. Transparency International U.S. Office Transparency International is a