Transcription

DedicationFor Mamaw and Papaw, my very ownhillbilly terminators

ContentsDedicationIntroductionChapter 1Chapter 2Chapter 3Chapter 4Chapter 5Chapter 6Chapter 7Chapter 8

Chapter 9Chapter 10Chapter 11Chapter 12Chapter 13Chapter 14Chapter 15ConclusionAcknowledgmentsNotesAbout the AuthorCreditsCopyrightAbout the Publisher

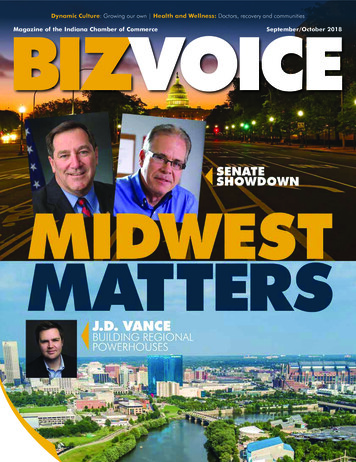

IntroductionMy name is J.D. Vance, and I think Ishould start with a confession: I find theexistence of the book you hold in yourhands somewhat absurd. It says rightthere on the cover that it’s a memoir, butI’m thirty-one years old, and I’ll be thefirst to admit that I’ve accomplishednothing great in my life, certainly nothingthat would justify a complete strangerpaying money to read about it. Thecoolest thing I’ve done, at least on

paper, is graduate from Yale LawSchool, something thirteen-year-old J.D.Vance would have considered ludicrous.But about two hundred people do thesame thing every year, and trust me, youdon’t want to read about most of theirlives. I am not a senator, a governor, or aformer cabinet secretary. I haven’tstarted a billion-dollar company or aworld-changing nonprofit. I have a nicejob, a happy marriage, a comfortablehome, and two lively dogs.So I didn’t write this book becauseI’veaccomplishedsomethingextraordinary. I wrote this book becauseI’ve achieved something quite ordinary,which doesn’t happen to most kids who

grow up like me. You see, I grew uppoor, in the Rust Belt, in an Ohio steeltown that has been hemorrhaging jobsand hope for as long as I can remember.I have, to put it mildly, a complexrelationship with my parents, one ofwhom has struggled with addiction fornearly my entire life. My grandparents,neither of whom graduated from highschool, raised me, and few members ofeven my extended family attendedcollege. The statistics tell you that kidslike me face a grim future—that ifthey’re lucky, they’ll manage to avoidwelfare; and if they’re unlucky, they’lldie of a heroin overdose, as happened todozens in my small hometown just last

year.I was one of those kids with a grimfuture. I almost failed out of high school.I nearly gave in to the deep anger andresentment harbored by everyone aroundme. Today people look at me, at my joband my Ivy League credentials, andassume that I’m some sort of genius, thatonly a truly extraordinary person couldhave made it to where I am today. Withall due respect to those people, I thinkthat theory is a load of bullshit.Whatever talents I have, I almostsquandered until a handful of lovingpeople rescued me.That is the real story of my life, andthat is why I wrote this book. I want

people to know what it feels like tonearly give up on yourself and why youmight do it. I want people to understandwhat happens in the lives of the poor andthe psychological impact that spiritualand material poverty has on theirchildren. I want people to understand theAmerican Dream as my family and Iencountered it. I want people tounderstand how upward mobility reallyfeels. And I want people to understandsomething I learned only recently: thatfor those of us lucky enough to live theAmerican Dream, the demons of the lifewe left behind continue to chase us.There is an ethnic component lurkingin the background of my story. In our

race-conscious society, our vocabularyoften extends no further than the color � “white privilege.” Sometimesthese broad categories are useful, but tounderstand my story, you have to delveinto the details. I may be white, but I donot identify with the WASPs of theNortheast. Instead, I identify with themillions of working-class whiteAmericans of Scots-Irish descent whohave no college degree. To these folks,poverty is the family tradition—theirancestors were day laborers in theSouthern slave economy, sharecroppersafter that, coal miners after that, andmachinists and millworkers during more

recent times. Americans call themhillbillies, rednecks, or white trash. Icall them neighbors, friends, and family.The Scots-Irish are one of the mostdistinctive subgroups in America. Asone observer noted, “In traveling acrossAmerica,theScots-Irishhaveconsistently blown my mind as far andaway the most persistent and unchangingregional subculture in the country. Theirfamily structures, religion and politics,and social lives all remain unchangedcompared to the wholesale abandonmentof tradition that’s occurred nearlyeverywhere else.”1 This distinctiveembrace of cultural tradition comesalong with many good traits—an intense

sense of loyalty, a fierce dedication tofamily and country—but also many badones. We do not like outsiders or peoplewho are different from us, whether thedifference lies in how they look, howthey act, or, most important, how theytalk. To understand me, you mustunderstand that I am a Scots-Irishhillbilly at heart.If ethnicity is one side of the coin,then geography is the other. When thefirst wave of Scots-Irish immigrantslanded in the New World in theeighteenth century, they were deeplyattracted to the Appalachian Mountains.This region is admittedly huge—stretching from Alabama to Georgia in

the South to Ohio to parts of New Yorkin the North—but the culture of GreaterAppalachia is remarkably cohesive. Myfamily, from the hills of easternKentucky, describe themselves ashillbillies, but Hank Williams, Jr.—bornin Louisiana and an Alabama resident—also identified himself as one in his ruralwhite anthem “A Country Boy CanSurvive.” It was Greater Appalachia’spolitical reorientation from Democrat toRepublican that redefined Americanpolitics after Nixon. And it is in GreaterAppalachia where the fortunes ofworking-class whites seem dimmest.From low social mobility to poverty todivorce and drug addiction, my home is

a hub of misery.It is unsurprising, then, that we’re apessimistic bunch. What is moresurprising is that, as surveys have found,working-class whites are the mostpessimistic group in America. Morepessimistic than Latino immigrants,many of whom suffer unthinkablepoverty. More pessimistic than blackAmericans, whose material prospectscontinue to lag behind those of whites.While reality permits some degree ofcynicism, the fact that hillbillies like meare more down about the future thanmany other groups—some of whom areclearly more destitute than we are—suggests that something else is going on.

Indeed it is. We’re more sociallyisolated than ever, and we pass thatisolation down to our children. Ourreligion has changed—built aroundchurches heavy on emotional rhetoric butlight on the kind of social supportnecessary to enable poor kids to dowell. Many of us have dropped out ofthe labor force or have chosen not torelocate for better opportunities. Ourmen suffer from a peculiar crisis ofmasculinity in which some of the verytraits that our culture inculcates make itdifficult to succeed in a changing world.When I mention the plight of mycommunity, I am often met with anexplanation that goes something like this:

“Of course the prospects for workingclass whites have worsened, J.D., butyou’re putting the chicken before the egg.They’re divorcing more, marrying less,and experiencing less happiness becausetheir economic opportunities havedeclined. If they only had better accessto jobs, other parts of their lives wouldimprove as well.”I once held this opinion myself, and Ivery desperately wanted to believe itduring my youth. It makes sense. Nothaving a job is stressful, and not havingenough money to live on is even moreso. As the manufacturing center of theindustrial Midwest has hollowed out, thewhite working class has lost both its

economic security and the stable homeand family life that comes with it.But experience can be a difficultteacher, and it taught me that this story ofeconomic insecurity is, at best,incomplete. A few years ago, during thesummer before I enrolled at Yale LawSchool, I was looking for full-time workin order to finance my move to NewHaven, Connecticut. A family friendsuggested that I work for him in amedium-sized floor tile distributionbusiness near my hometown. Floor tileis extraordinarily heavy: Each pieceweighs anywhere from three to sixpounds, and it’s usually packaged incartons of eight to twelve pieces. My

primary duty was to lift the floor tileonto a shipping pallet and prepare thatpallet for departure. It wasn’t easy, but itpaid thirteen dollars an hour and Ineeded the money, so I took the job andcollected as many overtime shifts andextra hours as I could.The tile business employed about adozen people, and most employees hadworked there for many years. One guyworked two full-time jobs, but notbecause he had to: His second job at thetile business allowed him to pursue hisdream of piloting an airplane. Thirteendollars an hour was good money for asingle guy in our hometown—a decentapartment costs about five hundred

dollars a month—and the tile businessoffered steady raises. Every employeewho worked there for a few yearsearned at least sixteen dollars an hour ina down economy, which provided anannual income of thirty-two thousand—well above the poverty line even for afamily. Despite this relatively stablesituation, the managers found itimpossible to fill my warehouse positionwith a long-term employee. By the time Ileft, three guys worked in the warehouse;at twenty-six, I was by far the oldest.One guy, I’ll call him Bob, joined thetile warehouse just a few months beforeI did. Bob was nineteen with a pregnantgirlfriend. The manager kindly offered

the girlfriend a clerical positionanswering phones. Both of them wereterrible workers. The girlfriend missedabout every third day of work and nevergave advance notice. Though warned tochange her habits repeatedly, thegirlfriend lasted no more than a fewmonths. Bob missed work about once aweek, and he was chronically late. Ontop of that, he often took three or fourdaily bathroom breaks, each over half anhour. It became so bad that, by the end ofmy tenure, another employee and I madea game of it: We’d set a timer when hewent to the bathroom and shout the majormilestones through the warehouse—“Thirty-five minutes!” “Forty-five

minutes!” “One hour!”Eventually, Bob, too, was fired.When it happened, he lashed out at hismanager: “How could you do this to me?Don’t you know I’ve got a pregnantgirlfriend?” And he was not alone: Atleast two other people, including Bob’scousin, lost their jobs or quit during myshort time at the tile warehouse.You can’t ignore stories like thiswhen you talk about equal opportunity.Nobel-winning economists worry aboutthe decline of the industrial Midwest andthe hollowing out of the economic coreof working whites. What they mean isthat manufacturing jobs have goneoverseas and middle-class jobs are

harder to come by for people withoutcollege degrees. Fair enough—I worryabout those things, too. But this book isabout something else: what goes on inthe lives of real people when theindustrial economy goes south. It’s aboutreacting to bad circumstances in theworst way possible. It’s about a culturethat increasingly encourages socialdecay instead of counteracting it.The problems that I saw at the tilewarehouse run far deeper thanmacroeconomic trends and policy. Toomany young men immune to hard work.Good jobs impossible to fill for anylength of time. And a young man withevery reason to work—a wife-to-be to

support and a baby on the way—carelessly tossing aside a good job withexcellent health insurance. Moretroublingly, when it was all over, hethought something had been done to him.There is a lack of agency here—afeeling that you have little control overyour life and a willingness to blameeveryone but yourself. This is distinctfrom the larger economic landscape ofmodern America.It’s worth noting that although I focuson the group of people I know—working-class whites with ties toAppalachia—I’m not arguing that wedeserve more sympathy than other folks.This is not a story about why white

people have more to complain aboutthan black people or any other group.That said, I do hope that readers of thisbook will be able to take from it anappreciation of how class and familyaffect the poor without filtering theirviews through a racial prism. To manyanalysts, terms like “welfare queen”conjure unfair images of the lazy blackmom living on the dole. Readers of thisbook will realize quickly that there islittle relationship between that specterand my argument: I have known manywelfare queens; some were myneighbors, and all were white.This book is not an academic study.In the past few years, William Julius

Wilson, Charles Murray, Robert Putnam,and Raj Chetty have authoredcompelling, well-researched tractsdemonstrating that upward mobility felloff in the 1970s and never reallyrecovered, that some regions have faredmuch worse than others (shocker:Appalachia and the Rust Belt scorepoorly), and that many of the phenomenaI saw in my own life exist acrosssociety. I may quibble with some of theirconclusions, but they have demonstratedconvincingly that America has aproblem. Though I will use data, andthough I do sometimes rely on academicstudies to make a point, my primary aimis not to convince you of a documented

problem. My primary aim is to tell a truestory about what that problem feels likewhen you were born with it hangingaround your neck.I cannot tell that story withoutappealing to the cast of characters whomade up my life. So this book is not justa personal memoir but a family one—ahistory of opportunity and upwardmobility viewed through the eyes of agroup of hillbillies from Appalachia.Two generations ago, my grandparentswere dirt-poor and in love. They gotmarried and moved north in the hope ofescaping the dreadful poverty aroundthem. Their grandchild (me) graduatedfrom one of the finest educational

institutions in the world. That’s the shortversion. The long version exists in thepages that follow.Though I sometimes change thenames of people to protect their privacy,this story is, to the best of myrecollection, a fully accurate portrait ofthe world I’ve witnessed. There are nocomposite characters and no etailswithdocumentation—reportcards,handwritten letters, notes on photographs—but I am sure this story is as fallibleas any human memory. Indeed, when Iasked my sister to read an earlier draft,that draft ignited a thirty-minute

conversation about whether I hadmisplaced an event chronologically. Ileft my version in, not because I suspectmy sister’s memory is faulty (in fact, Iimagine hers is better than mine), butbecause I think there is something tolearn in how I’ve organized the events inmy own mind.Nor am I an unbiased observer.Nearly every person you will read aboutis deeply flawed. Some have tried tomurder other people, and a few weresuccessful. Some have abused theirchildren, physically or emotionally.Many abused (and still abuse) drugs. ButI love these people, even those to whomI avoid speaking for my own sanity. And

if I leave you with the impression thatthere are bad people in my life, then I amsorry, both to you and to the people soportrayed. For there are no villains inthis story. There’s just a ragtag band ofhillbillies struggling to find their way—both for their sake and, by the grace ofGod, for mine.

Chapter 1Like most small children, I learned myhome address so that if I got lost, I couldtell a grown-up where to take me. Inkindergarten, when the teacher asked mewhere I lived, I could recite the addresswithout skipping a beat, even though mymother changed addresses frequently, forreasons I never understood as a child.Still, I always distinguished “myaddress” from “my home.” My addresswas where I spent most of my time with

my mother and sister, wherever thatmight be. But my home never changed:my great-grandmother’s house, in theholler, in Jackson, Kentucky.Jackson is a small town of about sixthousand in the heart of southeasternKentucky’s coal country. Calling it atown is a bit charitable: There’s acourthouse, a few restaurants—almostall of them fast-food chains—and a fewother shops and stores. Most of thepeople live in the mountains surroundingKentucky Highway 15, in trailer parks,in government-subsidized housing, insmall farmhouses, and in mountainhomesteads like the one that served asthe backdrop for the fondest memories of

my childhood.Jacksonians say hello to everyone,willingly skip their favorite pastimes todig a stranger’s car out of the snow, and—without exception—stop their cars,get out, and stand at attention every timea funeral motorcade drives past. It wasthat latter practice that made me awareof something special about Jackson andits people. Why, I’d ask my grandma—whom we all called Mamaw—dideveryone stop for the passing hearse?“Because, honey, we’re hill people. Andwe respect our dead.”My grandparents left Jackson in thelate 1940s and raised their family inMiddletown, Ohio, where I later grew

up. But until I was twelve, I spent mysummers and much of the rest of my timeback in Jackson. I’d visit along withMamaw, who wanted to see friends andfamily, ever conscious that time wasshortening the list of her favorite people.And as time wore on, we made our tripsfor one reason above all: to take care ofMamaw’s mother, whom we calledMamaw Blanton (to distinguish her,though somewhat confusingly, fromMamaw). We stayed with MamawBlanton in the house where she’d livedsince before her husband left to fight theJapanese in the Pacific.Mamaw Blanton’s house was myfavorite place in the world, though it

was neither large nor luxurious. Thehouse had three bedrooms. In the frontwere a small porch, a porch swing, anda large yard that stretched into amountain on one side and to the head ofthe holler on the other. Though MamawBlanton owned some property, most of itwas uninhabitable foliage. There wasn’ta backyard to speak of, though there wasa beautiful mountainside of rock andtree. There was always the holler, andthe creek that ran alongside it; thosewere backyard enough. The kids allslept in a single upstairs room: a squadbay of about a dozen beds where mycousins and I played late into the nightuntil our irritated grandma would

frighten us into sleep.The surrounding mountains wereparadise to a child, and I spent much ofmy time terrorizing the Appalachianfauna: No turtle, snake, frog, fish, orsquirrel was safe. I’d run around withmy cousins, unaware of the ever-presentpovertyorMamawBlanton’sdeteriorating health.At a deep level, Jackson was the oneplace that belonged to me, my sister, andMamaw. I loved Ohio, but it was full ofpainful memories. In Jackson, I was thegrandson of the toughest woman anyoneknew and the most skilled auto mechanicin town; in Ohio, I was the abandonedson of a man I hardly knew and a woman

I wished I didn’t. Mom visited Kentuckyonly for the annual family reunion or theoccasional funeral, and when she did,Mamaw made sure she brought none ofthe drama. In Jackson, there would be noscreaming, no fighting, no beating up onmy sister, and especially “no men,” asMamaw would say. Mamaw hatedMom’s various love interests andallowed none of them in Kentucky.In Ohio, I had grown especiallyskillful at navigating various fatherfigures. With Steve, a midlife-crisissufferer with an earring to prove it, Ipretended earrings were cool—so muchso that he thought it appropriate to piercemy ear, too. With Chip, an alcoholic

police officer who saw my earring as asign of “girlieness,” I had thick skin andloved police cars. With Ken, an odd manwho proposed to Mom three days intotheir relationship, I was a kind brother tohis two children. But none of thesethings were really true. I hated earrings,I hated police cars, and I knew thatKen’s children would be out of my lifeby the next year. In Kentucky, I didn’thave to pretend to be someone I wasn’t,because the only men in my life—mygrandmother’s brothers and brothers-inlaw—already knew me. Did I want tomake them proud? Of course I did, butnot because I pretended to like them; Igenuinely loved them.

The oldest and meanest of theBlanton men was Uncle Teaberry,nicknamed for his favorite flavor ofchewing gum. Uncle Teaberry, like hisfather, served in the navy during WorldWar II. He died when I was four, so Ihave only two real memories of him. Inthe first, I’m running for my life, andTeaberry is close behind with aswitchblade, assuring me that he’ll feedmy right ear to the dogs if he catches me.I leap into Mamaw Blanton’s arms, andthe terrifying game is over. But I knowthat I loved him, because my secondmemory is of throwing such a fit overnot being allowed to visit him on hisdeathbed that my grandma was forced to

don a hospital robe and smuggle me in. Iremember clinging to her underneath thathospital robe, but I don’t remembersaying goodbye.Uncle Pet came next. Uncle Pet wasa tall man with a biting wit and araunchy sense of humor. The mosteconomically successful of the Blantoncrew, Uncle Pet left home early andstarted some timber and constructionbusinesses that made him enough moneyto race horses in his spare time. Heseemed the nicest of the Blanton men,with the smooth charm of a successfulbusinessman. But that charm masked afierce temper. Once, when a truck driverdelivered supplies to one of Uncle Pet’s

businesses, he told my old hillbillyuncle, “Off-load this now, you son of abitch.” Uncle Pet took the commentliterally: “When you say that, you’recalling my dear old mother a bitch, soI’d kindly ask you speak morecarefully.” When the driver—nicknamedBig Red because of his size and haircolor—repeated the insult, Uncle Pet didwhat any rational business owner woulddo: He pulled the man from his truck,beat him unconscious, and ran anelectric saw up and down his body. BigRed nearly bled to death but was rushedto the hospital and survived. Uncle Petnever went to jail, though. Apparently,Big Red was also an Appalachian man,

and he refused to speak to the policeabout the incident or press charges. Heknew what it meant to insult a man’smother.Uncle David may have been the onlyone of Mamaw’s brothers to care littlefor that honor culture. An old rebel withlong, flowing hair and a longer beard, heloved everything but rules, which mightexplain why, when I found his giantmarijuana plant in the backyard of theold homestead, he didn’t try to explain itaway. Shocked, I asked Uncle Davidwhat he planned to do with illegal drugs.So he got some cigarette papers and alighter and showed me. I was twelve. Iknew if Mamaw ever found out, she’d

kill him.I feared this because, according tofamily lore, Mamaw had nearly killed aman. When she was around twelve,Mamaw walked outside to see two menloading the family’s cow—a prizedpossession in a world without runningwater—into the back of a truck. She raninside, grabbed a rifle, and fired a fewrounds. One of the men collapsed—theresult of a shot to the leg—and the otherjumped into the truck and squealedaway. The would-be thief could barelycrawl, so Mamaw approached him,raised the business end of her rifle to theman’s head, and prepared to finish thejob. Luckily for him, Uncle Pet

intervened. Mamaw’s first confirmedkill would have to wait for another day.Even knowing what a pistol-packinglunatic Mamaw was, I find this storyhard to believe. I polled members of myfamily, and about half had never heardthe story. The part I believe is that shewould have murdered the man ifsomeone hadn’t stopped her. She loatheddisloyalty, and there was no greaterdisloyalty than class betrayal. Each timesomeone stole a bike from our porch(three times, by my count), or broke intoher car and took the loose change, orstole a delivery, she’d tell me, like ageneral giving his troops marchingorders, “There is nothing lower than the

poor stealing from the poor. It’s hardenough as it is. We sure as hell don’tneed to make it even harder on eachother.”Youngest of all the Blanton boys wasUncle Gary. He was the baby of thefamily and one of the sweetest men Iknew. Uncle Gary left home young andbuilt a successful roofing business inIndiana. A good husband and a betterfather, he’d always say to me, “We’reproud of you, ole Jaydot,” causing me toswell with pride. He was my favorite,the only Blanton brother not to threatenme with a kick in the ass or a detachedear.My grandma also had two younger

sisters, Betty and Rose, whom I lovedeach very much, but I was obsessed withthe Blanton men. I would sit among themand beg them to tell and retell theirstories. These men were the gatekeepersto the family’s oral tradition, and I wastheir best student.Most of this tradition was far fromchild appropriate. Almost all of itinvolved the kind of violence that shouldland someone in jail. Much of it centeredon how the county in which Jackson ons, but they all had one theme:The people of Breathitt hated certain

things, and they didn’t need the law tosnuff them out.One of the most common tales ofBreathitt’s gore revolved around anolder man in town who was accused ofraping a young girl. Mamaw told methat, days before his trial, the man wasfound facedown in a local lake withsixteen bullet wounds in his back. Theauthorities never investigated themurder, and the only mention of theincident appeared in the localnewspaper on the morning his body wasdiscovered. In an admirable display ofjournalistic pith, the paper reported:“Man found dead. Foul play expected.”“Foul play expected?” my grandmother

would roar. “You’re goddamned right.Bloody Breathitt got to that son of abitch.”Or there was that day when UncleTeaberry overheard a young man state adesire to “eat her panties,” a referenceto his sister’s (my Mamaw’s)undergarments. Uncle Teaberry drovehome, retrieved a pair of Mamaw’sunderwear, and forced the young man—at knifepoint—to consume the clothing.Some people may conclude that Icome from a clan of lunatics. But thestories made me feel like hillbillyroyalty, because these were classicgood-versus-evil stories, and my peoplewere on the right side. My people were

extreme, but extreme in the service ofsomething—defending a sister’s honoror ensuring that a criminal paid for hiscrimes. The Blanton men, like thetomboy Blanton sister whom I calledMamaw, were enforcers of hillbillyjustice, and to me, that was the very bestkind.Despite their virtues, or perhapsbecause of them, the Blanton men werefull of vice. A few of them left a trail ofneglected children, cheated wives, orboth. And I didn’t even know them thatwell: I saw them only at large familyreunions or during the holidays. Still, Iloved and worshipped them. I onceoverheard Mamaw tell her mother that I

loved the Blanton men because so manyfather figures had come and gone, but theBlanton men were always there. There’sdefinitely a kernel of truth to that. Butmore than anything, the Blanton menwere the living embodiment of the hillsof Kentucky. I loved them because Iloved Jackson.As I grew older, my obsession withthe Blanton men faded into appreciation,just as my view of Jackson as some sortof paradise matured. I will always thinkof Jackson as my home. It isunfathomably beautiful: When the leavesturn in October, it seems as if everymountain in town is on fire. But for allits beauty, and for all the fond memories,

Jackson is a very harsh place. Jacksontaught me that “hill people” and “poorpeople” usually meant the same thing. AtMamaw Blanton’s, we’d eat scrambledeggs, ham, fried potatoes, and biscuitsfor breakfast; fried bologna sandwichesfor lunch; and soup beans and cornbreadfor dinner. Many Jackson familiescouldn’t say the same, and I knew thisbecause, as I grew older, I overheard theadults speak about the pitiful children inthe neighborhood who were starving andhow the town could help them. Mamawshielded me from the worst of Jackson,but you can keep reality at bay only solong.On a recent trip to Jackson, I made

sure to stop at Mamaw Blanton’s oldhouse, now inhabited by my secondcousin Rick and his family. We talkedabout how things had changed. “Drugshave come in,” Rick told me. “Andnobody’s interested in holding down ajob.” I hoped my beloved holler hadescaped the worst, so I asked Rick’sboys to take me on a walk. All around Isaw the worst signs of Appalachianpoverty.Some of it was as heartbreaking as itwas cliché: decrepit shacks rottingaway, stray dogs begging for food, andold furniture strewn on the lawns. Someof it was far more troubling. Whilepassing a small two-bedroom house, I

noticed a frightened set of eyes lookingat me from behind the curtains of abedroom window. My curiosity piqued,I looked closer and counted no fewerthan eight pairs of eyes, all looking at mefrom three windows with an unsettlingcombination of fear and longing. On thefront porch was a thin man, no older thanthirty-five, apparently the head of -updogsprotected the furniture strewn about thebarren front yard. When I asked Rick’sson what the young father did for aliving, he told me the man had no joband was proud of it. But, he added,“they’re mean, so we just try to avoid

them.”That house might be extreme, but itrepresents much about the lives of hillpeople in Jackson. Nearly a third of thetown lives in poverty, a figure thatincludes about half of Jackson’schildren. And that doesn’t count thelarge majority of Jacksonians who hoveraround the poverty line. An epidemic ofprescription drug addiction has takenroot. The public schools are so bad thatthe state of Kentucky recently seizedcontrol. Nevertheless, parents send theirchildren to these schools because theyhave little extra money, and the highschool fails to send its students tocollege with alarming consistency. The

people are physically unhealthy, andwithout government assistance they lacktreatment for the most basic problems.Most important, they’re mean about it—th

hillbilly at heart. If ethnicity is one side of the coin, then geography is the other. When the first wave of Scots-Irish immigrants landed in the New World in the eighteenth century, they were deeply attracted to the Appalachian Mountains. This region is admittedly huge— stretching from Alabama to Georgia in