Transcription

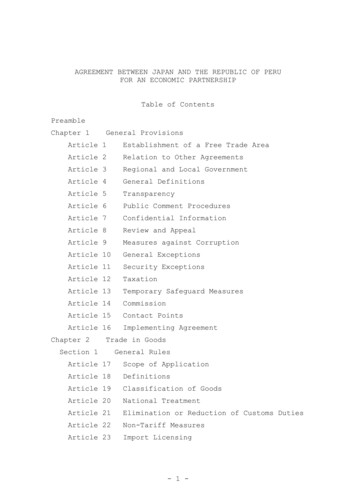

ARTICLE IIEXECUTIVE DEPARTMENTCONTENTSPageSection 1. The President .Clause 1. Powers and Term of the President .Nature and Scope of Presidential Power .Creation of the Presidency .Executive Power: Theory of the Presidential Office .Hamilton and Madison .The Myers Case .The Curtiss-Wright Case .The Youngstown Case .The Practice in the Presidential Office .Executive Power: Separation-of-Powers Judicial Protection .Tenure .Clauses 2, 3 and 4. Election .Electoral College .‘‘Appoint’’ .State Discretion in Choosing Electors .Constitutional Status of Electors .Electors as Free Agents .Clause 5. Qualifications .Clause 6. Presidential Succession .Clause 7. Compensation and Emoluments .Clause 8. Oath of Office .Section 2. Powers and Duties of the President .Clause 1. Commander-in-Chiefship; Presidential Advisers; Pardons .Commander-in-Chief .Development of the Concept .The Limited View .The Prize Cases .Impact of the Prize Cases on World Wars I and II .Presidential Theory of the Commander-in-Chiefship in World War II—and Beyond .Presidential War Agencies .Constitutional Status of Presidential Agencies .Evacuation of the West Coast Japanese .Presidential Government of Labor Relations .Sanctions Implementing Presidential Directives .The Postwar Period .The Cold War and After: Presidential Power to Use Troops Overseas WithoutCongressional Authorization .The Historic Use of Force Abroad .The Theory of Presidential Power .The Power of Congress to Control the President’s Discretion .The President as Commander of the Armed Forces 443444445447448450451453409

410ART. II—EXECUTIVE DEPARTMENTSection 2. Powers and Duties of the President—ContinuedClause 1. Commander-in-Chiefship; Presidential Advisers; Pardons—ContinuedThe Commander-in-Chief a Civilian Officer .Martial Law and Constitutional Limitations .Martial Law in Hawaii .Articles of War: The Nazi Saboteurs .Articles of War: World War II Crimes .Martial Law and Domestic Disorder .Presidential Advisers .The Cabinet .Pardons and Reprieves .The Legal Nature of a Pardon .Scope of the Power .Offenses Against the United States; Contempt of Court .Effects of a Pardon: Ex parte Garland .Limits to the Efficacy of a Pardon .Congress and Amnesty .Clause 2. Treaties and Appointment of Officers .The Treaty-Making Power .President and Senate .Negotiation, a Presidential Monopoly .Treaties as Law of the Land .Origin of the Conception .Treaties and the States .Treaties and Congress .Congressional Repeal of Treaties .Treaties versus Prior Acts of Congress .When Is a Treaty Self-Executing .Treaties and the Necessary and Proper Clause .Constitutional Limitations on the Treaty Power .Interpretation and Termination of Treaties as International Compacts .Termination of Treaties by Notice .Determination Whether a Treaty Has Lapsed .Status of a Treaty a Political Question .Indian Treaties .Present Status of Indian Treaties .International Agreements Without Senate Approval .Executive Agreements by Authorization of Congress .Reciprocal Trade Agreements .The Constitutionality of Trade Agreements .The Lend-Lease Act .International Organizations .Executive Agreements Authorized by Treaties .Arbitration Agreements .Agreements Under the United Nations Charter .Status of Forces Agreements .Executive Agreements on the Sole Constitutional Authority of the President .The Litvinov Agreement .The Hull-Lothian Agreement .The Post-War Years .The Domestic Obligation of Executive Agreements .The Executive Establishment 7

ART. II—EXECUTIVE DEPARTMENTSection 2. Powers and Duties of the President—ContinuedClause 2. Treaties and Appointment of Officers—ContinuedOffice .Ambassadors and Other Public Ministers .Presidential Diplomatic Agents .Appointments and Congressional Regulation of Offices .Congressional Regulation of Conduct in Office .The Loyalty Issue .Financial Disclosure and Limitations .Legislation Increasing Duties of an Officer .Stages of Appointment Process .Nomination .Senate Approval .When Senate Consent Is Complete .Commissioning the Officer .Clause 3. Vacancies during Recess of Senate .Recess Appointments .Judicial Appointments .Ad Interim Designations .The Removal Power .The Myers Case .The Humphrey Case .The Wiener Case .The Watergate Controversy .The Removal Power Rationalized .Other Phases of Presidential Removal Power .The Presidential Aegis: Demands for Papers .Private Access to Government Information .Prosecutorial and Grand Jury Access to Presidential Documents .Congressional Access to Executive Branch Information .Section 3. Legislative, Diplomatic, and Law Enforcement Duties of the President .Legislative Role of the President .The Conduct of Foreign Relations .The Right of Reception: Scope of the Power .The Presidential Monopoly .The Logan Act .A Formal or a Formative Power .The President’s Diplomatic Role .Jefferson’s Real Position .The Power of Recognition .The Case of Cuba .The Power of Nonrecognition .Congressional Implementation of Presidential Policies .The Doctrine of Political Questions .Recent Statements of the Doctrine .The President as Law Enforcer .Powers Derived from This Duty .Impoundment of Appropriated Funds .Power and Duty of the President in Relation to Subordinate Executive Officers .Administrative Decentralization Versus Jacksonian Centralism .Congressional Power Versus Presidential Duty to the Law .Myers Versus Morrison .Power of the President to Guide Enforcement of the Penal Laws 1562563

412ART. II—EXECUTIVE DEPARTMENTSection 3. Legislative, Diplomatic, and Law Enforcement Duties of the President—ContinuedThe President as Law Enforcer—ContinuedThe President as Law Interpreter .Military Power In Law Enforcement: The Posse Comitatus .Suspension of Habeas Corpus by the President .Preventive Martial Law .The Debs Case .Present Status of the Debs Case .The President’s Duty in Cases of Domestic Violence in the States .The President as Executor of the Law of Nations .Protection of American Rights of Person and Property Abroad .Congress and the President versus Foreign Expropriation .Presidential Action in the Domain of Congress—Steel Seizure Case .The Doctrine of the Opinion of the Court .The Doctrine Considered .Power Denied by Congress .Presidential Immunity from Judicial Direction .The President’s Subordinates .Section 4. Impeachment .Impeachment .Persons Subject to Impeachment .Judges .Impeachable Offenses .The Chase Impeachment .The Johnson Impeachment .Later Judicial Impeachments .The Nixon Impeachment .Judicial Review of Impeachments 83583584584586587588589589590

EXECUTIVE DEPARTMENTARTICLE IISECTION 1. The executive Power shall be vested in a President of the United States of America. He shall hold his Officeduring the Term of four Years and, together with the VicePresident, chosen for the same Term, be elected, as follows:NATURE AND SCOPE OF PRESIDENTIAL POWERCreation of the PresidencyOf all the issues confronting the members of the PhiladelphiaConvention, the nature of the presidency ranks among the mostimportant and the resolution of the question one of the most significant steps taken. 1 The immediate source of Article II was theNew York constitution in which the governor was elective by thepeople and thus independent of the legislature, his term was threeyears and he was indefinitely re-eligible, his decisions except withregard to appointments and vetoes were unencumbered with acouncil, he was in charge of the militia, he possessed the pardoningpower, and he was charged to take care that the laws were faithfully executed. 2 But when the Convention assembled and almost toits closing days, there was no assurance that the executive department would not be headed by plural administrators, would not beunalterably tied to the legislature, and would not be devoid ofmany of the powers normally associated with an executive.Debate in the Convention proceeded against a background ofmany things, but most certainly uppermost in the delegates’ mindswas the experience of the States and of the national governmentunder the Articles of Confederation. Reacting to the exercise ofpowers by the royal governors, the framers of the state constitutions had generally created weak executives and strong legislatures, though not in all instances. The Articles of Confederation1 The background and the action of the Convention is comprehensively examined in C. THACH, THE CREATION OF THE PRESIDENCY 1775–1789 (Baltimore: 1923).A review of the Constitution’s provisions being put into operation is J. HART, THEAMERICAN PRESIDENCY IN ACTION 1789 (New York: 1948).2 Hamilton observed the similarities and differences between the President andthe New York Governor in THE FEDERALIST, No. 69 (J. Cooke ed. 1961), 462–470.On the text, see New York Constitution of 1777, Articles XVII-XIX, in 5 F. THORPE,THE FEDERAL AND STATE CONSTITUTIONS, H. Doc. No. 357, 59th Congress, 2d sess.(Washington: 1909), 2632–2633.413

414ART. II—EXECUTIVE DEPARTMENTSec. 1—The PresidentCl. 1—Powers and Terms of the Presidentvested all powers in a unicameral congress. Experience had demonstrated that harm was to be feared as much from an unfetteredlegislature as from an uncurbed executive and that many advantages of a reasonably strong executive could not be conferred on thelegislative body. 3Nonetheless, the Virginia Plan, which formed the basis of discussion, offered in somewhat vague language a weak executive. Selection was to be by the legislature, and that body was to determine the major part of executive competency. The executive’s salary was, however, to be fixed and not subject to change by the legislative branch during the term of the executive, and he was ineligible for re-election so that he need not defer overly to the legislature. A council of revision was provided of which the executive wasa part with power to negative national and state legislation. Theexecutive power was said to be the power to ‘‘execute the nationallaws’’ and to ‘‘enjoy the Executive rights vested in Congress by theConfederation.’’ The Plan did not provide for a single or plural executive, leaving that issue open. 4When the executive portion of the Plan was taken up on June1, James Wilson immediately moved that the executive should consist of a single person. 5 In the course of his remarks, Wilson demonstrated his belief in a strong executive, advocating election bythe people, which would free the executive of dependence on thenational legislature and on the States, proposing indefinite re-eligibility, and preferring an absolute negative though in concurrencewith a council of revision. 6 The vote on Wilson’s motion was putover until the questions of method of selection, term, mode of removal, and powers to be conferred had been considered; subsequently, the motion carried, 7 and the possibility of the development of a strong President was made real.Only slightly less important was the decision finally arrived atnot to provide for an executive council, which would participate notonly in the executive’s exercise of the veto power but also in theexercise of all his executive duties, notably appointments and treaty making. Despite strong support for such a council, the Convention ultimately rejected the proposal and adopted language vesting3 C. THACH, THE CREATION OF THE PRESIDENCY 1775–1789 (Baltimore: 1923),chs. 1–3.4 The plans offered and the debate is reviewed in C. THACH, THE CREATION OFTHE PRESIDENCY 1775–1789 (Baltimore: 1923), ch. 4. The text of the Virginia Planmay be found in 1 M. FARRAND, THE RECORDS OF THE FEDERAL CONVENTION OF1787 (New Haven: rev. ed. 1937), 21.5 Id., 65.6 Id., 65, 66, 68, 69, 70, 71, 73.7 Id., 93.

ART. II—EXECUTIVE DEPARTMENTSec. 1—The President415Cl. 1—Powers and Terms of the Presidentin the Senate the power to ‘‘advise and consent’’ with regard tothese matters. 8Finally, the designation of the executive as the ‘‘President ofthe United States’’ was made in a tentative draft reported by theCommittee on Detail 9 and accepted by the Convention without discussion. 10 The same clause had provided that the President’s titlewas to be ‘‘His Excellency,’’ 11 and, while this language was also accepted without discussion, 12 it was subsequently omitted by theCommittee on Style and Arrangement 13 with no statement of thereason and no comment in the Convention.Executive Power: Theory of the Presidential OfficeThe most obvious meaning of the language of Article II, § 1, isto confirm that the executive power is vested in a single person,but almost from the beginning it has been contended that thewords mean much more than this simple designation of locus. Indeed, contention with regard to this language reflects the muchlarger debate about the nature of the Presidency. With JusticeJackson, we ‘‘may be surprised at the poverty of really useful andunambiguous authority applicable to concrete problems of executivepower as they actually present themselves. Just what our forefathers did envision, or would have envisioned had they foreseenmodern conditions, must be divined from materials almost as enigmatic as the dreams Joseph was called upon to interpret for Pharaoh. A century and a half of partisan debate and scholarly speculation yields no net result but only supplies more or less aptquotations from respected sources on each side of any question.They largely cancel each other.’’ 14 At the least, it is no doubt truethat the ‘‘loose and general expressions’’ by which the powers andduties of the executive branch are denominated 15 place the President in a position in which he, as Professor Woodrow Wilson noted,‘‘has the right, in law and conscience, to be as big a man as he can’’and in which ‘‘only his capacity will set the limit.’’ 168 Thelast proposal for a council was voted down on September 7. 2 id., 542.185.10 Id., 401.11 Id., 185.12 Id., 401.13 Id., 597.14 Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer, 343 U.S. 579, 634–635 (1952) (concurring opinion).15 A. UPSHUR, A BRIEF ENQUIRY INTO THE TRUE NATURE AND CHARACTER OFOUR FEDERAL GOVERNMENT (Petersburg, Va.: 1840), 116.16 W. WILSON, CONSTITUTIONAL GOVERNMENT IN THE UNITED STATES (NewYork: 1908), 202, 205.9 Id.,

416ART. II—EXECUTIVE DEPARTMENTSec. 1—The PresidentCl. 1—Powers and Terms of the PresidentHamilton and Madison.—In Hamilton’s defense of PresidentWashington’s issuance of a neutrality proclamation upon the outbreak of war between France and Great Britain may be found notonly the lines but most of the content of the argument that ArticleII vests significant powers in the President as possessor of executive powers not enumerated in subsequent sections of Article II. 17Said Hamilton: ‘‘The second article of the Constitution of the United States, section first, establishes this general proposition, that‘the Executive Power shall be vested in a President of the UnitedStates of America.’ The same article, in a succeeding section, proceeds to delineate particular cases of executive power. It declares,among other things, that the president shall be commander in chiefof the army and navy of the United States, and of the militia ofthe several states, when called into the actual service of the UnitedStates; that he shall have power, by and with the advice and consent of the senate, to make treaties; that it shall be his duty to receive ambassadors and other public ministers, and to take care thatthe laws be faithfully executed. It would not consist with the rulesof sound construction, to consider this enumeration of particularauthorities as derogating from the more comprehensive grant inthe general clause, further than as it may be coupled with expressrestrictions or limitations; as in regard to the co-operation of thesenate in the appointment of officers, and the making of treaties;which are plainly qualifications of the general executive powers ofappointing officers and making treaties.‘‘The difficulty of a complete enumeration of all the cases of executive authority, would naturally dictate the use of general terms,and would render it improbable that a specification of certain particulars was designed as a substitute for those terms, whenantecedently used. The different mode of expression employed inthe constitution, in regard to the two powers, the legislative andthe executive, serves to confirm this inference. In the article whichgives the legislative powers of the government, the expressions are,‘All legislative powers herein granted shall be vested in a congressof the United States.’ In that which grants the executive power, theexpressions are, ‘The executive power shall be vested in a Presidentof the United States.’ The enumeration ought therefore to be considered, as intended merely to specify the principal articles impliedin the definition of executive power; leaving the rest to flow fromthe general grant of that power, interpreted in conformity withother parts of the Constitution, and with the principles of free gov17 32 WRITINGS OF GEORGE WASHINGTON, J. Fitzpatrick ed. (Washington: 1939),430. See C. THOMAS, AMERICAN NEUTRALITY IN 1793: A STUDY IN CABINET GOVERNMENT (New York: 1931).

ART. II—EXECUTIVE DEPARTMENTSec. 1—The President417Cl. 1—Powers and Terms of the Presidenternment. The general doctrine of our Constitution then is, that theexecutive power of the nation is vested in the President; subjectonly to the exceptions and qualifications, which are expressed inthe instrument.’’ 18Madison’s reply to Hamilton, in five closely reasoned articles, 19was almost exclusively directed to Hamilton’s development of thecontention from the quoted language that the conduct of foreign relations was in its nature an executive function and that the powersvested in Congress which bore on this function, such as the powerto declare war, did not diminish the discretion of the President inthe exercise of his powers. Madison’s principal reliance was on thevesting of the power to declare war in Congress, thus making it alegislative function rather than an executive one, combined withthe argument that possession of the exclusive power carried withit the exclusive right to judgment about the ob

414 ART. II—EXECUTIVE DEPARTMENT Sec. 1—The President Cl. 1—Powers and Terms of the President 3 C. THACH, THE CREATION OF THE PRESIDENCY 1775-1789 (Baltimore: 1923), chs. 1-3. 4 The plans offered and the debate is reviewed in C. THACH, THE CREATION OF THE PRESIDENCY 1775-1789 (Baltimore: 1923), ch. 4. The text of the Virginia Plan may be found in 1 M. FARRAND, THE RECORDS OF THE .