Transcription

Arts, Health andWell-Being across theMilitary ContinuumWHITE PAPER AND FRAMINGA NATIONAL PLAN FOR ACTION

www.ArtsAcrossTheMilitary.org

Arts, Health and Well-Being across the Military ContinuumWhite Paper and Framing a National Plan for ActionTABLE OF CONTENTS2012 National Roundtable: Summary ofDiscussion about Research30A Message from2013 National Summit: Summary of Discussionabout Research30Summary314Rear Admiral Alton L. Stocks, SHCE, USN,Commander, Walter Reed Bethesda6A Brief History of Arts in the MilitaryBy Robert L. Lynch, President & CEO, Americans for the Arts8Executive SummaryChapter 3: Practice32Starting an Arts and Health Program orService in the Military32Healthcare Facilities33Community Settings3536Collaborating for Action: The NationalInitiative for Arts & Health in the Military9Key Considerations in PracticeResearch Recommendations9Practice Recommendations92012 National Roundtable: Summary of Discussionabout Practice 2013 National Summit37Policy Recommendations102013 National Summit: Summary of Discussionabout Practice38Moving Forward: A Call to Action11Summary39Introduction—Laying the Groundwork for ActionEnvisioning a National Plan for Action byOpening a National DialogueChapter 1: The Arts, Health, and Well-Being121315Chapter 4: Policy40Military Initiatives40National Initiatives41Corporate Initiatives41Why Do Humans Engage in the Arts?15Key Considerations in Policy42How Art Works16Arts in Health and Well-Being162012 National Roundtable: Summary ofDiscussion about Policy42Defining a Continuum of Arts andHealth Practitioners172013 National Summit: Summary ofDiscussion about Policy43Implications for Arts and Health acrossthe Military ContinuumSummary4419Chapter 2: Research20Conclusion: Choosing to Lead TogetherReferences454650Post-Traumatic Stress21Traumatic Brain Injury22Depression24APPENDIX A: DEFINITIONSPhysical Injuries and Illnesses25The Military Continuum26APPENDIX B: ARTS & HEALTH IN THE MILITARY NATIONALROUNDTABLE—Participants54Art and Design28Key Considerations in Research29AppendicesAPPENDIX C: SUGGESTED ACTIVITIESTO ADDRESS RECOMMENDATIONSAcknowledgements505558

A Message fromRear Admiral Alton L. StocksIn the fall of 2011, the congressionally mandated integration of Walter Reed Army Medical Center(WRAMC) and the National Naval Medical Center (NNMC) officially took place. NNMC was renamedas Walter Reed National Military Medical Center (WRNMMC), in Bethesda, MD. Also known as thePresident’s hospital, Walter Reed Bethesda is the largest military medical center in the UnitedStates—a tertiary care destination providing services in over 100 clinics and specialties for nearly1 million patient visits a year including wounded warriors and their family members.Often the first destination in the continental United States forthe wounded, ill, and injured from global conflicts, Walter ReedBethesda also provides care for the President and Vice Presidentof the United States, Members of Congress, and Justices of theSupreme Court and, when authorized, provides care for foreignmilitary and embassy personnel. The Walter Reed Bethesdacampus is also home to the National Intrepid Center of Excellence(NICoE), a 72,000-square-foot facility dedicated to advancingthe clinical care, diagnosis, research, and education of servicemembers and families experiencing combat related traumaticbrain injury (TBI) and psychological health (PH) conditions.One might ask, “What has art got to do with it?” Surprisinglyto some, the answer is “plenty.” Through our Creative ArtsProgram, the arts have been a growing component of thehealth and healing services we provide for our service menand women, their families, as well as staff. Partnerships withartists and arts groups, such as ArtStream’s Allies in the Arts,Musicorps, and Smith Center for Healing and the Arts, providea broad range of projects and experiences in multiple artisticdisciplines for wounded service members and their families.Walter Reed Bethesda’s Department of Psychiatry hosts monthlyperformances for staff, patients, and family through the Stages ofHealing program, which also includes bedside performances inindividual wards and patient rooms.The Healing Arts Program at the NICoE integrates art into thepatient’s continuum of care, providing each individual sufferingunder the effects of traumatic brain injuries and psychologicalhealth conditions with new tools in artistic and creativemodalities—including creative writing, music, and visual art—to mitigate anxiety or trouble focusing, as well as to provide anonverbal outlet to help service members express themselvesand process traumatic experiences. Creative arts therapists atNICoE work with partners such as the National Endowment forthe Arts’ Operation Homecoming to expand artistic outlets forpatients and their families.In October of 2011, I hosted the first National Summit: Artsin Healing for Warriors at Walter Reed Bethesda and theNICoE. The 2011 Summit was the first time various branches ofthe military collaborated with civilian agencies to discuss howengaging with the arts provides opportunities to meet the keyhealth issues our military faces and a key strategy to help heal ourwounded warriors.Arts, Health and Well-Being across the Military ContinuumWhite Paper and Framing a National Plan for Action4

The success of the first Summit led to the launching of theNational Initiative for Arts & Health in the Military, aneffort that Walter Reed National Military Medical Center is pleasedto be co-chairing along with Americans for the Arts. In Novemberof 2012, the second major event in this movement, the Arts &Health in the Military National Roundtable, took place andresulted in the first policy paper, Arts, Health, and Well-Being acrossthe Military Continuum, which recommends collective actions tohelp increase access to the arts as tools for healing and wellnessfor all military service men and women, medical staff, veterans,their families, and caregivers.Finding solutions requires action and partnershipsacross military, government, nonprofit, and forprofit sectors. The recommendations presentedin Arts, Health and Well-Being across the MilitaryContinuum—White Paper and Framing a NationalPlan for Action are the next steps in this continuingdialogue—and a starting place for understandinghow each of us can do our part.Rear Admiral Alton L. Stocks, SHCE, USN,Commander, Walter Reed BethesdaThe second National Summit: Arts, Health, and Well-Beingacross the Military Continuum held in April 2013, again atWalter Reed Bethesda, took this conversation one step further.We examined the benefits of the arts not just for woundedwarriors, but across the entire military continuum, includingpre-deployment, deployment, reintegration into community andfamily, veteran, and late-life care. And we asked the more than200 military, health, and arts professionals in attendance how wecan, by working together, advance the mission of the NationalInitiative to make the arts part of health, healing, and healthcareacross the entire military continuum. Their voices and ideas arereflected in this White Paper.The challenges service members face are more complex anddifficult than any branch of the military, federal agency, or civilianorganization can address alone. We have seen first-hand thesuccess and value of creative arts programs and will continueexpanding our arts programs through partnerships with artistsand arts organizations to ensure those who are in most needhave access.The labyrinth meditation room at the National Intrepid Center ofExcellence at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Bethesda,MD. Courtesy of NICoE.Arts, Health and Well-Being across the Military ContinuumWhite Paper and Framing a National Plan for Action5

A Brief History of Arts in the Militaryby Robert L. LynchI have always been fascinated by a quote from John Adams: “I must study politics and war, thatmy sons may have the liberty to study mathematics and philosophy, geography, natural historyand naval architecture, in order to give their children a right to study painting, poetry, music,architecture, statuary, tapestry, and porcelain.” John Adams clearly valued the arts and alsounderstood that the freedom to engage in the arts for our citizenry was linked to the ability ofour citizens and military to secure the peace and create a strong nation.The link between our U.S. military and the arts goes back a longway to the very beginnings of our nation. Our founding fatherswere learned individuals and well aware that the arts—visualart, music, poetry, dance, drama—had all played a vital role inthe militaries of ancient civilizations and even prehistoric times.General George Washington was passionate about theater, somuch so that he commissioned a performance of Addison’s Catoat Valley Forge to inspire his Continental Army. And passagesfrom this very play, this work of art, went on to inspire some ofour great American patriotic quotations: “Give me liberty or giveme death” from Patrick Henry and, “I regret that I have but onelife to give for my country,” spoken by Nathan Hale.The arts went beyond inspiration, too—they were embeddedin the tactics and strategy of everyday battle. Military bands inAmerica go all the way back to an artillery regiment commandedby none other than Benjamin Franklin in 1756. Ben Franklinwas later asked by General George Washington to help bringdiscipline through movement to the rag tag Continental Armyof 1778. So Franklin enlisted Prussian Officer Baron Friedrich VonSteuben to come to Valley Forge and teach the art of the drill,which instilled discipline and attention to detail in the troops andhas been core to military preparation ever since. In fact, musicianswere a critical component of all of America’s early militias, wheredrummers, the Internet of their day, would send out calls to aregion that it was time to assemble and take up arms. Fife anddrum units were there not just for entertainment and diversionbut to provide sound signals to soldiers to execute variousmovements and orders in the midst of the smoke and the chaosof battle.That function was not limited to the battlefield. In 1798, just 30days after our U.S. Navy Department was formed, the USS Gangesrecruited to its decks 21 privates, one sergeant, one corporal, andtwo musicians as essential personnel for a cramped ship of war.And just think of the role of the bugle, which was introducedlater, probably around the War of 1812. Music through thisinstrument has been used to order the life of the military fromdawn to dusk for the last 200 years, up to and including at theend of that life: “Taps,” which was adapted and introduced forthat purpose by Union General Daniel Butterfield in July 1862, hasstood in for the sadness of individuals and for an entire nationduring these most solemn times.By the time America was engaged in World War II, 500 bandswere serving the U.S. Army, and the War Department hadestablished an emergency Army Music School and a schoolfor bandmasters at the Army War College. The employment ofthe arts through bands and musicians for inspiration, discipline,ceremony, battle, and healing continued through our warsin Korea, Vietnam, Desert Storm, and right through to today’smilitary conflicts.Arts, Health and Well-Being across the Military ContinuumWhite Paper and Framing a National Plan for Action6

When we start to look closely in this way, it seems almostobvious: of course music is everywhere in the military, and it iseasy to see (and hear) its impact. Yet it is not alone. Art in all itsforms is interwoven throughout the history of our U.S. military,but it is just not often pointed out as such.President Abraham Lincoln called for the dome of the U.S.Capitol—a piece of magnificent architecture employingsculpture, painting, glasswork, and skilled craftsmanship inboth wood and stone—to be completed in the middle of theCivil War. Though at first the timing might sound unwise, themonumental and artistic nature of the construction providedthe best vehicle for Lincoln to convey and embody—in a highlyvisible symbol—hope and the promise of our future, as well asmake a statement about who we are as a nation. It is no accidentthat on September 11, 2001, this symbol was targeted for aterrorist attack.One of the very biggest museums in Washington, DC, a cityof museums, serves another function, too, for which it is morefamous. That building is the Pentagon, but its acres of hallwaysand spaces are filled with centuries of paintings, sculptures,dioramas, photos, and art explaining battles, military actions andthe related political issues, and commemorating the fallen. At theWest Point Museum, I was fascinated to see beautiful paintingsdone by famous military leaders like Ulysses S. Grant or WilliamTecumseh Sherman. In fact, drawing courses were a core part ofthe cadet curriculum well into the 20th century1, and The New YorkTimes pointed out that in recent years, poetry has been offered asone way to teach cadets to deal with ambiguity in an increasinglycomplex world.2Sometimes the art connection has been more spontaneous, likethe practice of World War II air servicemen to name their aircraftand paint the noses and sides to illustrate “Snake Eyes” or “TheDragon Lady” to create a human connection to the team and themachines upon which they depended.And sometimes, the art connection is so deep and so critical,very few people know about it at all. A few years back, I had thehonor of sitting at dinner with the great American contemporaryartist Ellsworth Kelly, and he told me a story that astonished me.1“The History of Art at West Point.” The Creative Arts Project at West Point. %20Art%20at%20West%20Point.aspx2Samet, Elizabeth D. “In the Valley of the Shadow.” New York Times. Published30 September 2007. URL: oint-t.html?pagewanted all& r 0He told me of the 23rd Headquarters Special Troops, U.S. Army,nicknamed the Ghost Army, in which he served during World WarII. Classified until 1996, this was a 1,100-man unit of the U.S. Armymade up entirely of artists, painters, actors, sound engineers,writers, and others. It was designed to create disinformation—likethe famous inflatable tanks that the artist-soldiers of the GhostArmy invented to confuse the enemy and create advantage forour U.S. forces.The art connection has been there for centuries now, but oftenwe simply see it as something else. In my grandfather’s PurpleHeart medal most of us see an important symbol of sacrifice; it isalso a small sculpture by an artist, based on a commissioned printby an artist, and designed as a medal by another artist, to be oneof our nation’s most honored and treasured statements.As a people and a nation, we stand up for a poem, the “StarSpangled Banner.” We are inspired and moved by a song, themusic for our national anthem. We salute a visual art creation, andcall it Old Glory, the flag of our nation. And we reach for the artsto tell our story at every solemn and joyous occasion we have inour military and in our secular lives.Today, the arts and military connection is biggerand stronger than ever—but still not obvious. Fromart and craft instruction in recreation facilities onbases throughout the world, to the extensive militarymusic program, to battle photography and visualart battlefront illustration, to the use of writingand theater programs for service men and womenreturning from war, to art and music therapy andarts healing programs for the wounded, the artstoday are there as a partner, as a support system, asa friend to the military—as they have been since thebeginning of our great nation.Robert L. Lynch, President & CEO,Americans for the ArtsArts, Health and Well-Being across the Military ContinuumWhite Paper and Framing a National Plan for Action7

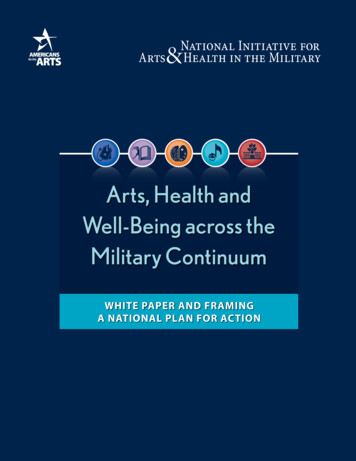

Introduction: Laying the Groundwork for ActionExecutive SummaryToday’s military faces urgent challenges. Military service canbe difficult, demanding, and dangerous (Morin, 2011). Over thecourse of the 20th and 21st centuries, the United States has sentmillions of men and women into harm’s way to defend Americaninterests and to protect our allies and weaker nations. Yet therehave been differences in recent wars. While overall the combatdeath rate has decreased, an increasing proportion of servicemembers return home with severe injuries, some visible, someinvisible (Eastridge et al., 2012).Returning to civilian life has its own challenges, and veteransreport difficulty adjusting, especially those who have servedsince the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks (Morin, 2011).According to the U.S. Department of Housing and UrbanDevelopment (2012), about 10 percent of our homeless citizenson a single night in 2012 were veterans. Combat trauma has leftone out of every three Iraq and Afghanistan veterans with PostTraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI), or acombination of the two (Tanielian & Jaycox, 2008).Military service constitutes a major influence on the lifespan ofservice members and veterans, presenting multiple challengesacross the military continuum associated with mission readiness,deployment, family readiness, and reintegration into thecommunity post-deployment. A variety of common transitions,such as enlistment, training, or deployment, have an impact onindividuals’ cognitive and behavioral performance. Often oneof the most difficult of these experiences is the transition frommilitary to civilian life. The National Center for Veterans Analysisand Statistics (2010) projects that there are more than 22 millionveterans in the United States today, with the largest number fromthe Vietnam era (see Figure 1).There are significant challenges for families as well. Servicemembers make incredible sacrifices and put themselves inharm’s way for the sake of us all: “They do not make thesesacrifices alone. When our troops are called to action, so too aretheir families” (Joining Forces, n.d.).An all-volunteer military force has left many individuals andcommunities feeling disconnected from these growingchallenges. The draft of the past had a leveling effect; everyoneknew someone who served. Today, with only 1 percent of thepopulation in military service, it is common for many individualsto not know anyone who serves (Pew Research, 2011). Withoutpersonal connections, communities are often out of touch withthe issues confronting service members, veterans, and theirfamilies, and may not be aware of these issues or how they mighthelp. This is in fact one of the “unintended consequences” ofsuccess—the United States having the best military in the worldand a truly professional military force.Figure 1: Veterans by Period of ServiceFrom U.S. Census Bureau, 2012.Gulf War to present25%9%10%24%Vietnam eraKorean conflict32%World War IIPeacetimeArts, Health and Well-Being across the Military ContinuumWhite Paper and Framing a National Plan for Action8

Executive SummaryCollaborating for Action: The NationalInitiative for Arts & Health in the MilitaryIn the spring of 2010, a small group of arts and health leadersand military leaders began a conversation about the role of thearts in addressing these challenging issues, and in October 2011the National Summit: Arts in Healing for Warriors was heldto explore the possibilities. The following year the NationalInitiative for Arts & Health in the Military was established towork across military, government, private, and nonprofit sectors to:1. advance the policy, practice, and quality use of arts andcreativity as tools for health in the military;2. raise visibility, understanding, and support of arts and health inthe military; and3. make the arts as tools for health available to all active dutymilitary, medical staff, family members, and veterans.To date, the National Initiative, co-chaired by Americans for theArts and Walter Reed National Military Medical Center with acoalition of public and private sector agencies, has implementedtwo additional important convenings: the Arts & Health inthe Military National Roundtable (November 2012), and theNational Summit: Arts, Health and Well-being across theMilitary Continuum (April 2013). Participants at these meetingswere asked to propose recommendations for action to furtherthe National Initiative’s goals. From these meetings came a seriesof recommendations in the areas of research, practice, and policy.Research RecommendationsResearchers are looking at the impact of arts in health programsand services across the military continuum. The National Initiativefor Arts & Health in the Military defines this continuum as (a) predeployment/active duty, (b) re-entry/reintegration, (c) veterans/VA and community systems, (d) late-life veteran care, and (e)families/caregivers.We must strengthen the growing body of knowledge concerningthe health benefits of arts programming and creative artstherapies in the military and veteran populations. Researchersshould be encouraged and supported to investigate the manyways the arts can have an impact—physically, emotionally,economically, educationally—on the lives of service members,veterans, families, healthcare providers, and the community.1. Support a broad research agenda. Current federalinteragency efforts to invest in and broaden the arts andhealth research agenda, specifically in the military, should beopen to a wide range of possibilities and be expanded to takeadvantage of important research efforts taking place in theprivate and nonprofit sector. Both quantitative and qualitativeresearch methods should be supported. Although scientificevidence is crucial, anecdotal accounts—the stories—play afundamental role in humanizing the arts and health movementand in helping the community at large understand itsimportance. Above all, supporting a broad research agendathat incorporates a variety of methods and tools is the mostpromising path for improving practice.2. Seek research opportunities to link to others beyond thefields of arts, health, and the military. Arts and health inthe military research has implications for policy in other areasof health—stress reduction, employment, trauma, suicideprevention, resiliency—presenting additional opportunities forcollaborative studies and most importantly, the potential forbroader impact.3. Establish a central research depository. A central locationto house research findings on an online, accessible, searchabledatabase will promote sharing of research and expeditefuture research. It will also provide the essential knowledgethat practitioners need to develop effective evidence-basedpractices and policies.4. Conduct a needs assessment and benchmark research.A comprehensive needs assessment is required to determineand address needs, or “gaps,” between current conditionsand desired conditions, or “wants.” Benchmarking willmeasure the quality of an organization’s policies, products,programs, and strategies, and compare them with standardor similar measurements of others in the arts and health inthe military field. Identifying best practice will help both oldand new programs and services determine what and whereimprovements are needed to match these standards.Practice RecommendationsWe must create mechanisms to inform the expansion andeffectiveness of existing programs and the development ofnew ones. We can foster best practice by applying and sharingevidence-based principles at all stages of arts programming:planning, preparation, implementation, and evaluation. We canArts, Health and Well-Being across the Military ContinuumWhite Paper and Framing a National Plan for Action9

Executive Summaryexpand the knowledge base of providers in the arts, health, andmilitary by encouraging reciprocal training in arts and health bestpractices. For resource efficiency, every effort should be made toleverage existing military programs during implementation (e.g.,the Army’s Ready and Resilient Campaign and its ComprehensiveSoldier and Family Fitness program that provides resiliencetraining to soldiers, their family members, and Army civilians).1. Develop training programs for artists and performers,artists in healthcare, arts coordinators, and healthcareproviders. The military, healthcare, and arts fields representdistinct cultures, each with its own body of knowledge,terminology, philosophies, rules, and regulations. An effectivearts and health workforce requires training to ensure thatartists and performers and artists in healthcare possess specificknowledge and skills to enable them to work safely andsuccessfully within the military culture, including knowing thelimits of one’s preparation and when to refer to a mental healthprofessional. Informed and enlightened healthcare providerswill reduce barriers to the initiation of arts programmingthroughout the military and veteran healthcare systems andthe community at large. As we learn about potential benefitsof arts programming in helping service members and theirfamilies leverage resilience skills to increase unit readinessand enhance performance, we can create champions for themovement as well as provide tools for physicians, nurses, andallied health members to use the arts in their own practice.2. Incorporate family-centered arts programming atall stages of military service and beyond. The arts andcreative arts therapies will play an important role in troopreadiness and service and family member resiliency, duringpre-deployment, deployment, post-deployment, and acrossthe military continuum and individual’s lifespan.3. Engage artists and performers, artists in healthcare,arts organizations, and creative arts therapists at thegrassroots level. Many individuals and organizations arestanding by eager to help, but do not know how. Connectingthem through existing networks of nonprofit organizations willharness that power. Veteran artists will be celebrated as livingexamples of the efficacy of the arts in the military. Militaryand veteran artists also have a valuable role as mentors forwounded service members at the grassroots level.4. Establish an online presence to promote informationsharing, collaboration, and samplings of interactivearts experiences. An online resource for service members,veterans, and their families; healthcare providers; artists andperformers, artists in healthcare, arts organizations, andcreative arts therapists; and policy- and decision-makers, willpromote and increase service member, veteran, and familymember access to the arts in the healthcare system, at homebases/duty stations, and in the community at large.5. Get the word out. A variety of educational materials andmethods will be required to generate understanding andgarner broad support to fulfill the National Initiative’s goal ofincreasing access to the arts for service members, veterans,their family members, and providers.Policy RecommendationsWe must develop policies to ensure that every service member,veteran, family member, and caregiver has access to the artsand creative arts therapies, as appropriate. Arguably, the term“policy” has different meanings depending on the context andcircumstances in which it is being employed. Because of thediverse cross-sector representation of views, we consider policybroadly to include actions and guidelines, both formal andinformal, that can be implemented, monitored, and evaluated—including, but not limited to, specific organizational policies,government laws, and private sector practices.1. Promote the inclusion of the arts and creative artstherapies in national health and military strategicagency and department plans and interagencyinitiatives. Examples include expanding the work ofthe Federal Interagency Task Force on Arts and HumanDevelopment (led by the National Endowment for theArts) to include additional focus on the military, as wellas incorporation of the arts and creative arts therapiesin developing federal agency plans, such as the NationalPrevention Strategy (Office of the Surgeon General).2. Promote increased interagency and private sectorsupport and expedite funding for research. Currentresearch shows great promise for the efficacy of arts andhealth in the military for service members, veterans,families, providers, and the community. Expedited fundingwill allow researchers to build on this nascent but rich baseof knowledge.3. Increase policies that provide for the support ofcreative arts therapists within the Department ofDefense and Veterans Administration. Budgets willArts, Health and Well-Being across the Military ContinuumWhite Paper and Framing a National Plan for Action10

Executive Summaryrecognize the importance of creative arts therapists asmembers of the healthcare team. Trained clinical creative artstherapists will be integrated where appropriate and regardedas a reimbursable service.4. Encourage increased public and private sectorfunding for program development, implementation,and evaluation, and bringing successful programs toscale. Especially in light of the still challenging economyand decreasing public funding across the board, public andprivate collaboration is essential for encouraging the initiationof promising ideas and the sustainability of programs thathave proven effective. Strategic investment now will laythe groundwork for consideration of “scaling up” effectiveprograms once the economy recovers.5. Delineate an “Arts & Health in the Military” continuumof services, including the use of creative arts therapies,therapeutic arts, and arts for educational andexpressive purposes. Policies will address the inclusion ofarts in wellness; the concept of person-centered care, that onesize does not fit all; timeline variations for wounded servicemembers; and healing as a lifelong process that includestransition into employment and/or educational opportunities,aging, and end of life.6. Recognize that artists and performers and artistsin healthcare rendering these services are valuedprofessionals. Policies wil

How Art Works 16 Arts in Health and Well-Being 16 Defining a Continuum of Arts and Health Practitioners 17 Implications for Arts and Health across . By the time America was engaged in World War II, 500 bands were serving the U.S. Army, and the War Department had established an emergency Army Music School and a school