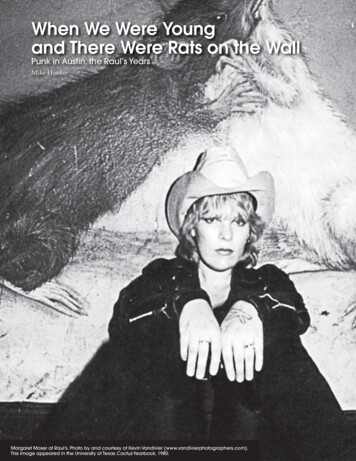

Transcription

Nietzsche and the Vicious Circle

The Universiry o f Chicago Press. Chicago 60637The Athlone Press, London. N W 11 7SGFirst published in France in 1969 byMercure de France, Paris asNietzsche et Ie Cerde Vidcux Editions Mercure de France 1969English translation The Athlone Press 1997Printed in Great Britain06 05 04 03 02 01 00 99 98 9712 3 4 5 6ISBN: 0-226-44386-8 (doth)ISBN: 0-226-44387-6 (paperback)Publisher's noteThe publishers wish to record their thanks to the FrenchMinistry of Culture for a grant towards the cost oftranslation.library of Congress Cataloging in Publication DataKlossowski, Pierre.[Nietzsche et le cercle vicieux. English]Nietzsche and the vicious circle I Pierre Klossowski ; trarulated by Daniel W. Smith.p. cm.Includes bibliographical references and index.ISBN 0-226-44386-8 (doth : alk. paper). —ISBN 0-226-44387-6 (pbk : alk. paper)1. Nietzsche, Friedrich W ilhelm, 1844-1900.I. Title.B3317.K6213 1997193-dc2197-14379CIPThis book is printed on add-free paper.

ContentsTranslator’s PrefaceIntroductionviixiv1 The Combat against Culture12 The Valetudinary States at the Origin of a Semiotico f Impulses153 The Experience of the Eternal Return554 The Valetudinary States at the Origin of FourCriteria: Decadence, Vigour, Gregariousness,the Singular Case745 Attempt at a Scientific Explanation of theEternal Return936 The Vicious Circle as a Selective Doctrine1217 The Consultation of the Paternal Shadow1728 The Most Beautiful Invention o f the Sick1989 The Euphoria of Turin20810 Additional Note on Nietzsche's Semiotic254NotesIndex262274

T o GiUes Deleuze

Translator’s PrefacePierre Klossowski’s Nietzsche and the Vicious Circle Franksalongside Martin Heidegger’s Nietzsche and Giles Deleuze'sNietzsche and Philosophy as one of the most important andinfluential, as well as idiosyncratic, readings of Nietzsche tohave appeared in Europe.1 W hen it was originaly publishedin 1969, Michel Foucault, who frequently spoke of hisindebtedness to Klossowski’s work, penned an enthusiasticletter to its author. ‘It is the greatest book of philosophy Ihave read,’ he wrote, ‘with Nietzsche himself.'2 Nietzsche andthe Vicious Circle was in fact the result of a long apprenticeship.Under the influence of Georges Bataille, Klossowski fintbegan reading Nietzsche in 1934, ‘in competition withl{jerkegaard’. 3 During the next three decades, he publisheda number o f occasional pieces on Nietzsche: an articlein a special issue of the journal Acephale devoted to thequestion o f ‘Nietzsche and the Fascists' (1937); reviews ofKarl Lowith’s and Karl Jasper’s books on Nietzsche (1939);an introduction to his own translation of The Gay Science(1954); and most importantly, a lecture presented to theCoUege de Philosophic entitled ‘Nietzsche, polytheism, andparody' (1957), which Deleuze later praised for having‘renewed the interpretation of Nietzsche’.4It was not until the 1960s, however, that K.lossowski seemsto have turned his full attention to Nietzsche. NieUsche and

viiiNietzsche and the Vicious Circlethe Vicious Cicc/e grew out of a paper entitled ‘Forgettingand anamnesis in the lived experience of the eternal returnof the same'. which Klossowski presented at the famousRoyaumont conference on Nietzsche in July 1964.5 Overthe next few years, Klossowski published a number ofadditiona! articles that were ultimately gathered togetherin Nietzsche and the Vicious Cicde in 1969.b The primaryinnovation of the study lay in the importance it gave toNietzsche's experience of the Eternal Return at Sils-Mariain August 188 1, of which Klossowski provided a new andhighly original interpretation. The book was one o f theprimary texts in the explosion of interest in Nietzsche thatoccurred in France around 1970,7 and it exerted a profoundinfluence on Deleuze and Guaruri’s Anti-Otdipus (1972) andLyotard's Libidinal Economy (1975).8 In July 1972, a secondmajor conference on Nietzsche took place in France atCerisy-la-Sale, which included presentations by Deleuze,Derrida, Lyotard, Nancy, Lacoue-Labarthe and Gandilac,among many others. Klossowski's contribution was a paperentitled ‘Circulus viriosus’, which analysed what he called the‘conspiracy' (complot) of the eternal return. It was the last texthe would write on Nietzsche.9Klossowski is himself a rather idiosyncratic figure whosework on Nietzsche constitutes merely one aspect of anextraordinary and rather enigmatic career. The older brotherof the painter Balthus, he was born in Paris in 1905 into an oldPolish family, and in his youth was a close friend and discipleof Rainer Maria Ri1ke and Andre Gide. In the 1930s heparticipated in the College de Sociologie with Michel Leiris,Roger Calois and Georges BataiUe, with whom he main tained a lifelong friendship. In 1939 he entered a Dominicanseminary, where he studied scholasticism and theology, butthen underwent a religious crisis during the Occupation. In1947, after having participated in the French Resistance, hereturned to the lay life, married, and wrote a now-famousstudy of the Marquis de Sade entitled Sade M y Neighbor. 10 Hisfirst novel, The Suspended Vocation (1950), was a transposition

Translator’s Prefaceixof the vicissitudes of his religious crisis." During the nextdecade. he wrote what is perhaps his most celebrated work,I1ie Laws of Hospitality, a trilogy that includes The Revocationof the Edict of Nantes (1959), Roberte, ce soir (1954), and LeSot!fenr (1960), and in which he created Roberte, thecentral sign of his entire oeuvre. In 1965, he published TheBapltomet, an aUegorical version of the Eternal Return thatreceived the coveted Prix des Critiques. 13 During this period,he also produced numerous translations of German and Latintexts, including works by Benjamin, b , K ierke d,Heidegger, Hamaan, Wittgenstein, Rilke, Klee, Nietzsche,Suetonius and Virgil. Since the publication, in 1970, of LivingCurrency, an essay on the economy and the affects, Klossowskihas devoted himself almost exclusively to painting.14 His large'compositions', as he cals them, executed in coloured pencilson paper, frequently transpose scenes from his novels, andhave been exhibited in Paris, Zurich, Berne, Cologne, NewYork, Tokyo, Rome. Madrid and elsewhere.15 Through out all these endeavours, Klossowski has remained almostunclassifiable, singular. Novelist, essayist, translator, artist, hecategoricallyrefuses the designation 'philosopher'. 'je suis un“maniaque’7 he says. 'U n point, c'est tout.M6 It is hopedthat this translation of Nietzsche and the Vicious Circleprovoke renewed interest in Klossowski’s remarkable workin the English-speaking world.Klossowski describes his books on Nietzsche and Sade as'essays devoted not to ideologies but to the physiognomies ofproblematic thinkers who differ greatly from each otherV 7He has developed an idiosyncratic vocabulary to describesuch physiognomies, and some of his tenninological inno vations deserve comment here.(1) The term fond has a wide range of meanings in French(‘bottom ', ‘ground', ‘depth’, ‘heart', ‘background' and so on),and has been translated unifonnJy here as ‘depth'. Klossowskialmost always uses it in the context of the expression fefond in&hangeable (‘the unexchangeable depth') or le fondunintelligible (‘the unintelligible depth'), which refen to the

XNietzsche and the Vicious Circle'obstinate singularity' of the human soul that is by naturenon-communicable.(2) Impulsion has been rendered throughout as ‘impulse',and its cognate impulsionnel as 'impulsive'. The term isrelated to the French pulsion, which translates the Freudianterm Triebe ('drive’), but which Klossowski uses only inrare instances. Nietzsche himself had recourse to a variedvocabulary to describe what Klossowski sununarizes in theterm ‘impulse': 'drive' (Triebe), 'desire* (&gierden), 'instinct’(Instinke), 'pow er' (Miichte), ’force’ (Krofte), 'impulse' (Reize,Impulse), ‘passion' (Leidenschtiften), 'feeling' (Geflilen). ‘affect'(Affekte), ‘pathos’ (Pathos), and so on. ,B The essential pointfor Klossowski is that these te ra refer to intensive states ofthe soul that are in constant fluctuation.(3) Klossowski's use of the term 'soul' (dme) is in partderived from the theological literature of the mystics, forwhom the unexchangeable depth of the soul was irreducibleand uncreated; it eludes the exercise of the created intel lect, and can be grasped only negatively.” If there is anapophaticism in Klossowski, however, it is related exclusivelyto the immanent movements of the soul’s intensive affects,and not to the transcendence of God. Klossowski frequentlyemploys the French term tonalite to describe these states o f thesoul's fluctuating intensities (their diverse tones, timbres andamplitudes). Since this use of the term is as unusual in Frenchas it is in English, we have retained the English 'tonality’ asits equivalent.(4) PhanttJSme ('phantasm') and simulacrum (’simulacrum')are perhaps the most important te u in Klossowski’svocabulary. The former comes from the Greek phantasia(appearance, imagination), and was taken up in a more tech nical sense in psychoanalytic theory; the latter comes from theLatin simulare (to copy. represent, feign), and during the lateRoman empire referred to the statues of the gods that linedthe entrance to a city. In Klossowski, the term 'phantasm'refers to an obsessional image produced instinctively fromthe life of the impulses. ‘My true themes', writes Klossowski

Translator's PrefaceXIof himself. 'are dictated by one or more obsessional (or"obsidianal”) instincts that seek to express themselves. A ‘simulacrum’, by contrast. is a w iled reproduction ofa phantasm (in a literary, pictorial, or plastic form) thatsimulates this invisible agitation of the soul. 'The simulacrum,in its imitative sense, is the actualization of something in itselfincommunicable and nonrepresentable: the phantasm in itsobsessional constraint.'21 If Nietzsche and the Vicious Circleis primarily an interpretation of Nietzsche’s physiognomy,it is because it attempts to identify the impulses or powersthat exercised their constraint on Nietzsche (notably thoseassociated with his valetudinary states), the phantasms theyproduced (notably the phantasm of the Eternal Return thatNietzsche experienced at Sils-Maria in August 1881), and thevarious simulacra Nietzsche created to express them.(5) Simulacra stand in a complex relationship to whatKlossowski, in his later works, calls a stereotype ('stereo type'). 22 O n the one hand, the invention of simulacraalways presupposes a set of prior stereotypes - what hehere calls 'the code of everyday signs' - that express thegregarious aspect of a lived experience in a form schematizedby the habitual usages of feeling and thought. In this sense,the code of everyday signs, by making them intelligible,necessarily invens and falsifies the singularity of the soul'sintensive movements: 'H ow can one give an account o f anirreducible depth of sensibility except by acts that betray it?123On the other hand, Klossowski also speaks of a 'science ofstereotypes’ in which the stereotype, by being 'accentuated*to the point of excess, can itself bring about a critique of itsown gregarious interpretation of the phantasm: 'Practicedadvisedly, the institutional stereotypes (of syntax) provoke thepresence of what they circumscribe; their circumlocutionsconceal the incongruity of the phantasm but at the m e timetrace the outline ofits opaque physiognomy. 4Klossowski’s own prose is an example of this latter 'scienceof sterotypes*. By his own admission, it is written in a“'conventionaly" classical syntax* that makes systematic

xiiNietzsche and the Viaous Circleuse of the literary tenses and conjunctions of the Frenchlanguage, giving it a decidedly erudite and even ‘bourgeois'tone. At the same time, however, it is also sprinkled withminor grammatical improprieties and solecisms: certain ofKlossowski's phrasings tum out to be fragments that arelinked together through a profuse utilization of colons, semi colons, and dashes, which often run the length of an entireparagraph. While we have tried to follow Klossowsk.i's syntaxas closely as possible, it has been impossible to reproducemany of his stylistic devices, and we have often elected tochoose intelligible English renderings. perhaps at the cost ofsacrificing some of his stylistic effects. Klossowski often makesuse of the present historique tense in the French, which we havegeneraUy translated by the past tense in the English.(6) We have translated the unusual but important termsuppot as ‘agent'. The word is derived from the Latinsuppositum, ‘that which is placed under'. In contemporaryusage, it refers to a subordinate who acts on behalf ofsomeone else. such as a ‘secret agent', and usually impliesthat the subordinate is carrying out the designs o f a wickedsuperior (suppot de Satan is a current French locution for a‘hellhound’ or evil person; the suppots de la tyrannie referto the ‘henchmen' of a tyrant or a tyrannicaJ regime). ButKlossowski's use of the term also refers back to a more distantand technical philosophicaJ history. In scholastic philosophy,the Latin suppositum was closely linked to the terms substantia(‘substance') or subjectum (‘subject'). In particular. it referredto a complete and individual subject that has its ownexistence, integrating heterogenous elements into a uniquewhole.25 In sixteenth- and seventeenth-century philosophy,the French suppot retained an analogous meaning, thoughit was applied to new philosophical problems.26 Klossowskiin tum has retrieved the term from the scholastic tradition,and applied it to a specificaUy Nietzschean problematic. Thesuppot is itself a phantasm, a complex and fragile entity thatbestows a psychic and organic unity upon the movingchaos of the impulses, primarily through the m a tic a l

Translator's Prefacefiction of the ‘I’, which interprets the impulses in te re ofa hierarchy o f gregarious needs {both material and moral), anddissimulates itself through a network o f concepts (substance,cause. identity, self, world, God) that reduces the combat ofthe impulses to silence.27 Unfortunately, there is no obvioustranslation for the term suppot: the English word ‘suppost’survived through the nineteenth century, but is now archaic.The term ‘agent’, while it does not adequately render .al thesenuances, nonetheless has the advantage of connoting boththe colloquial and philosophical senses o f suppot. The threeinstances, in Chapter 3, where Klossowski uses the Frenchterm agent (‘the agent of meaning’) a.re indicated clearly inthe text.Moi has generaly been translated as ‘self; however, it isalso the French translation of the Freudian ‘ego’, and wehave adopted d ls translation in contexts (such as Chapter 9)where Klossowski makes explicit reference to Freud.This translation would not have been completed withoutthe support of a Chateaubriand Fellowship from the Frenchgovernment, and a doctoral fellowship from the ChicagoHumanities Institute at the University of Chicago. Theirgenerosity is gratefuUy acknowledged. Elisabeth Beauregard,Peter Canning, Christoph Cox, Michael Greco, EleanorKaufinan, Tracy McNulty, Graham Parkes and Alan Schriftprovided welcome advice on various aspects of the trarnhtion. I consulted an earlier translation of Chapter 3 by A lenS. Weiss, which appeared in The New Nietzsche: ContemporaryStyles of Interpretation, ed. David B. Allison (New York: D elta1977), pp. 107-20.

IntroductionThis is a book thatexhibit an unusual ignorance. Howcan we speak solely of ‘Nietzsche’s thought’ without takinginto account everything that has subsequently been said aboutit? WiU we not thereby run the risk of foUowing paths thathave already been travelled more than once, blazing trailsthat have been marked out many times - imprudently askingquestions that have long ago been left behind? And wiU wenot in this way reveal a negligence, a total lack of scrupleswith regard to the meticulous exegeses that recently havebeen written - in order to interpret, as so many signals, theflashes of summer lightning that a destiny continues to sendour way from the horizon of our century?What then is our aim - if indeed we have one? Let us saythat we have written a false study. Because we are readingNietzsche’s texts directly, because we are listening to himspeak, can we perhaps make him speak to 'us'? Can weounelves make use of the whisperings, the breathings, thebunts of anger and laughter in what may be the mostingratiating - and also the most irritating - prose yetwritten in the German language? For those who can hearit, the word of Nietzsche gains a power that is al the moreexplosive insofar as contemporary history. current events.and the univene are beginning to answer, in a more orless circuitous manner, the questions Nietzsche was asking

Introductionxvsome eighty years ago. Nietzsche was interrogating thenear and distant future, a future that has now become oureveryday reality - and he predicted that this future wouldbe convulsive, to the point where our own convulsions arecaricatures of his thought. W etry to comprehend howand in what sense Nietzsche's interrogation describes what weare now living through.W e must not overlook two essential points that havehitherto remained veiled, if not passed over in silence, inthe study of his thought. The first is that, as Niettsche’sthought unfolded, it abandoned the strictly speculative realmin order to adopt, if not simulate, the preliminary elementso f a conspiracy. h thereby made our o era the object ofa tacit accusation. The indictment had been handed down bythe Marxist exegesis, which had at least exposed the intentionof the conspiracy, since every individual thought of bourgeoisorigin necessarily reveals its complicity in a class ‘conspiracy’.But there is a Niewchean conspiracy which is not that o f aclass but that of an isolated individual (like Sade), who usesthe means of this class not only against his own class, but alsoagainst the existing fo u of the human species as a whole.The second point is closely related to the first. BecauseNietzsche’s thought meditated on a lived experience tothe point where it became inverted into a systematic pre meditation, prey to an interpretative delirium that seemedto diminish the ‘responsibility of the thinker’, there is atendency to grant it, as it were, ‘extenuating circumstances’- which is worse than the Marxist indictment. For whatdo we want to extenuate? The jccl that his thought revolvedaround delirium as irs axis. Now early on, Niettsche wasapprehensive about this propensity in himseli; and his everyeffort was directed toward fighting the irresistible attractionthat Chaos (or, more precisely, the ‘chasm’) exerted on- a hiatus which, starting in his childhood, he strove to filin and cross over through his autobiography. The more heprobed the phenomenon of thought and the different behavioursthat result from it, and the more he studied the individual

Nietzsche and the Vicious Circlcreactions provoked by the structures of the modern world(and always in relation to his conception of the ancient world),the closer he drew to this chasm.Lucid thought, delirium and the conspiracy form anindissoluble whole in Nietzsche - an indissolubility thatwould become the criterion for discerning what is ofconsequence or not. This does not mean that, since itinvolved delirium, Nietzsche's thought was ‘pathological’;rather, because his thought was lucid to the extreme, ittook on the appearance of a delirious interpretation - andalso required the entire experimental initiative of the modemworld. It is modernity that must now be charged withdetermining whether this initiative has failed or succeeded.But because the world is itself concerned with Nietzsche’sinitiative, the more the modem world experiences the threatof its own failures, the more Nietzsche's thought gains instature. Modem catastrophes are always confused - in themore or les short term - with the ‘good news’ of a ‘falseprophet’. a t then is the act of thinking? There was a suspicion lurkingsilendy in the writings of Nietzsche’s youth, which came tothe fore in an increasingly virulent way in the unpublished m ents contemporaneous with Human, AH too Human and,especially, The Gay Science. What is lucid and what is unconsaousin our thought and in our actions? - a subterranean questionthat disguised itself outwardly in a critique of culture, and thatintentionaUy made itself explicit in a form that could stiU beintegrated into the speculative and historical discussions ofhis time. Niettsche’s thought thus foUowed, in an absolutelysimultaneous manner, two divergent movements: the notionof lucidity was valid only to the degree that total obscuritycontinued to be envisioned, and thus affirmed:‘At every moment chaos is stil pursuing its work in ourmind: conccpts, images, feelings are there juxtaposedfortuitously, thrown together pell-meU. In this way,

Introductionxviirelations that astonish the mind are created; the mindrecalls something similar, it feels a flavor, it retains andelaborates both according to its an and its knowledge.- Here is the last small fragment of the world wheresomething new is produced, at least as far as the humaneye is concerned. In sum, here again it is a matter o f anew chemical combination, which as yet has no parallelin the becoming of the world.28A thought only rises by falling, it progresses only by regressing- an inconceivable spiral, which to describe as ’useless’ isso repugnant to us that we are wary even of admitting thatsuccessive generations follow the same movement - evenif this means that we associate ourselves with the rise ofa m ind only as long as it seems to follow, in unison withculture, the ascent of history. As for the remainder, weleave the descending movement of this spiralling thoughtto those who specialize in the failures, the dregs, the wasteproducts produced by the function of thinking and living experts who, in accordance with this convenient division oflabour, hardly need to concern themselves with this tensionbetween lucidity and obscurity, except perhaps to note, onthe day when each reaches a verdict on the other, that theyhad picked up the accent of delirium.To want to detect this accent in Nietzsche’s thought wouldfrom the outset require us to consult the very authoritiesthat his thought called into question. Either Nietzsche wasdelirious from the outset in even wanting to attack theseauthorilies; or else he was dear-sighted in attacking thevery notion of lucidity directly. This is why, at every step,Nietzsche’s thought found itself circumscribed:on the inside:by the principle of identity on which language (the code ofeveryday signs) depends, in accordance with the realityprinciple;

XviiiNietzsche and the Vicious Circleon the outside:by competent institutional authorities (the historians ofphilosophy), but also and above all by the psychiatrists, thesurveyors of the unconscious who, for this very reason,control the more or less variable range of the realityprinciple, to which the person who thinks or acts wouldbear witness;finaly:on both sides, by science and its experimentations, whichsometimes separates and sometimes brings the two together,thus displacing the boundaries and 'adjusting' the demarca tions between the inside and the oulside.Pu long as Nietzsche respected these variously delimitedspheres from the viewpoint of inquiry, his understandingseemed to comply with two principles: the principle of reality(insofar as he simply described reality historically, he analysedit in order to reconstruct it, and thus to communicate theresults of his research to others) and the principle of identily(insofar as he defined himself as a teacher in relation to whathe was teaching).But once the demonstration (required by institutionallanguage for the teaching of reality) was turned into themovmenl of a declarative mood, and the contagious mood ortonality of the soul supplanted the demonstration, Nietzschereached the limit of the principles of identity and reality,which were answerable lo the very authorities his own discoursewas presumably based upon. Nietzsche introduced intoteaching what no authority responsible for the transmission ofknowledge (philosophy) had ever been advised to teach. ButNietzsche introduced it surreptitiously, his language on thecon trary having pushed to an extreme severity the applicationof the laws required for communication. The tonality of thesoul, in making itself thought, was pursuing its own inquiry,to the point where the te w of the latter were reconstituted asa muteness: this thought spoke to itself o f an obstacle that theintenlion to teach would stumble over at the outset.

IntroductionThis obstacle, whose muteness was experienced as intensityand resistance, put the aim ofteaching itself in question. Nowthe resistance of the mute obstacle was nothing other than thevirtual reaction exerted by the authorities of identity and reality.Muteness on the inside was merely speech on the outside.The assent (assentiment) of thought to this speech on theoutside was merely the resentmenl (ressentiment) of the moodor the mute tonality. Nietzsche’s declarations transferred themuteness of the mood onto thought, insofar as the moodcame up against the resistance of culture from without (thatis. the speech of universities, scientists, authorities, politicalparties, priests, doctors).In identifying himselfwith this mule obstacle of the mood inorder to think it, 'Professor Nietzsche' destroyed not onlyhis own identity but that of the authorities of speech. Asa consequence, he suppressed their presence within hisdiscourse, and along with their presence, he suppressed thereality principle itself. His declarations were directed to anoutside that he had reduced to the silence of his own moods.Though they were reduced to silence in Nietzsche'sdeclarations, however, the speaking agencies had never beenanything other than the configuration of his moods. The muteintensity of the soul's tonality could be sustained only as longas a resistance from the outside was still speaking: culture.Culture (the sum total of knowledge) - that is, theintention to teach and learn - is the obverse of thesoul’s tonality, its intensity, which can be neither taughtnor learnt. The more culture accumulates, however, themore it becomes enslaved to itself - and the more itsobverse. the mute intensity of the tonality of the soul, grows.The soul's tonality catches the teacher by surprise, and finailybreaks with the intention to teach: the servitude of culturethus breaks forth at the moment it collides with the mutenesso f Nietzsche's discourse.Since Professor Nietzsche's ultima veverba turned into aphasia,it is easy for doctors to see th.is as a confirmation of theirown reality principle: Nietzsche went beyond the limits, he

XXNietzsche and the Vicious Circlelapsed into incoherence, he ceased to speak, he howled orremained silent.No one sees that science itself is aphasic, and that if itadmitted it had no foundation, no reality would subsist from which it derives a power that induces it to calculate:it is this decision that invents reality. It calculates so as notto have to speak, for fear of falling back into nothingness.

1The Combat against CultureI. Is the ‘philosopher’ still possible today? Is the extento f what is known too great? Is it not unlikely that heever manage to embrace everything within his vision,al the less so the more scrupulous he is? Would it nothappen too late, when his best time is past? O r at thevery least. when he is damaged, degraded, degenerated,so that his value judgement no longer means anything?In the opposite case, hebecome a dilettante witha thousand antennae, having lost the great pathos, hisrespect for himself - the good, subtle conscience.Enough - he no longer either directs or commands.If he wanted to, he would have to become a great actor,a kind of Cagliostro philosopher.2. W hat does a philosophical existence mean for ustoday? Isn’t it almost a way of withdrawing? A kind ofevasion? And for someone who lives that way, apart andin complete simplicity, is it likely that he has indicatedthe best path to foUow for his own knowledge? W ouldhe not have had to experiment with a hundred differentways o f living to be authorized to speak of the value oflife? In short, we think it is necessary to have lived in atotaUy ‘antiphilosophical' manner, according to hithertoreceived notions, and certainly not as a shy man ofvirtue - in order to judge the great problems from livedexperiences. The man with the greatest experiences,who condenses them into general conclusions: would

2Nielzschcandthc i'iciotts Circlehe not have to be the most powerful nun? - For a longtime we have confused the Wist" MJ.n with the scientificman, and for an even longer time with the religiouslyexalted man.2 1Only now has it dawned on humanity that music isa semiological language of affects: and later welearn how to recognize dearly the impulsive systemof a musician through his music. In truth, he didnot intend to betray himself in this manner. Such is theinnocence of this type of confession, as opposed to everywritten work.Yet this innocence also exists in the great philo sophers: they are not conscious that they are speakingof themselves - they claim it would be a question of‘the truth* - when at bottom it is only a question ofthemselves. O r rather: their most violent impulse isbrought to light with al the impudence and innocenceof a fun m ental impulse: it wants to be sovereign and,if possible, the aim of every thing and every event!The philosopher is only a kind of occasion and chancethrough which the impulse isfina/ly able to speak.There are many more languages than we think: andman betrays himself more often than he desires. Howthings speak! - but there are very few listeners, so thatman can only, as it w

8 The Most Beautiful Invention of the Sick 198 9 The Euphoria of Turin 208 10 Additional Note on Nietzsche's Semiotic 254 Notes Index 262 274. To GiUes Deleuze. . obsessional constraint.'21 If Nietzsche and the Vicious Circle is primarily an interpretation of Nietzsche's physiognomy,