Transcription

DEADLYSECRETSA REPORT BY INTERNATIONAL LABOR RIGHTS FORUMBUILDING A JUST WORLD FOR WORKERS

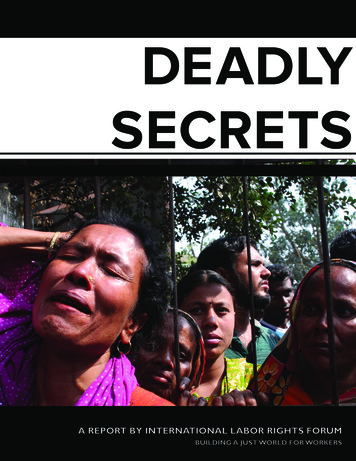

DEADLYSECRETSWHAT COMPANIES KNOW ABOUT DANGEROUS WORKPLACESAND WHY EXPOSING THE TRUTH CAN SAVE WORKERS’ LIVES INBANGLADESH AND BEYONDAuthor: Björn ClaesonDecember ing and proofreading: Judy Gearhart with LianaFoxvog, Laura Gutierrez, and Dan SmithInterview with Lovely: Trina ToccoResearch on factory fires: Robert J.S. Ross with HannaClaeson and Shannon FlowersLayout and design: Haley Wrinkle with Hanna Claesonrelating to the Bangladeshi garment industry.We wish to thank the National Garment WorkersFederation in Bangladesh and the Bangladesh Centerfor Worker Solidarity for their research and reports onBangladeshi garment workers’ wages, social security,housing, and living conditions. The development of thecore ideas for this report has benefitted from our frequentcritical conversations with colleagues at the Clean ClothesCampaign, the IndustriALL Global Union, the MaquilaSolidarity Network, and the Worker Rights Consortium.ILRF remains solely responsible for the views expressed inthis report.The International Labor Rights Forum (ILRF) is an advocacyorganization based in Washington, DC. ILRF is dedicatedto achieving just and humane treatment for workersworldwide and serves a unique role among human rightsorganizations as advocates for and with working poorpeople around the world. We believe that all workershave the right to a safe working environment where theyare treated with dignity and respect, and where they canorganize freely to defend and promote their rights andinterests.We are also grateful for the 21st Century ILGWU Fund,which has supported our research and educational work1634 I Street NW, Suite 1001Washington, D.C. 20006www.laborrights.orgCorporate social responsibility staff of several companiesthat appear in this report critiqued an earlier version. Wehope that their comments have helped us better explainour arguments for ending the deadly secrets in theindustry.Cover photo: Workers mourn the loss of relatives in thefire at the Garib & Garib factory on February 25, 2010.Photographer: Taslima Akhter, taslimaakhter.com.INTERNATIONAL LABOR RIGHTS FORUMBUILDING A JUST WORLD FOR WORKERS

----------------------------------Executive Summary8Chapter 1:Garments of Poverty or Threads to Riches?12Chapter 2:They Know the Perils to Workers19Chapter 3:Cheap Labor and Fighting Workers29Chapter 4:What’s to Be Done: The Views of Government, Companies, and Workers37Conclusion:Let’s Seize the Opportunity for a New Bangladeshi Bargain44Epilogue:Is One Month in Jail, Two Years in Court, and the Death of a Colleague the Price for Organizing?DEADLY SECRETS463

Prologue: Lovelyfor her injuries. Just 17 years old at the time of ourinterview with her, she describes a ruined -------------------------------On February 23, 2006, a factory fire at the KTSTextile Factory in the city of Chittagong, Bangladesh,claimed the lives of 63 trapped garment workers,including young girls. Locked exits preventedworkers from escaping the fire. One media sourcereported that it was possible the main gate wasintentionally locked at the time of the fire to preventtheft from the factory. Other sources reported thatthere was no fire safety equipment at the factory, norhad there ever been a fire drill.Lovely, who was 11 years old at the time of the fire,barely survived. Her face is deformed and shesuffered burns all over her body. She appears frail.ILRF spoke with her in Dhaka, Bangladesh, five yearsafter the fire. She never received compensationChild labor in Bangladeshi garment factories wasnot common in 2006 and is virtually non-existenttoday. But it still serves us well to let Lovely, thechild, be the face of the horrors of the fires. Let usremember her story and her appeal to us as wework towards real safety for workers in Bangladeshand -------ILRF: We can start with your name, how old you are,and where you come from.Lovely: My name is Lovely. I’m from Banskhali, inChittagong, and I’m 17 years old.ILRF: Tell me about your family. Do you havebrothers and sisters, maybe a dog?Lovely: Yes, I have a family. I have two sisters andLovely. Photo: ILRFDEADLY SECRETS4

two brothers, and I have my parents.ILRF: And are you the oldest, or the middle or theyoungest?Lovely: I’m the second one of five.ILRF: Talk with me about why you went to work in thefactory.Lovely: I’m from a poor family, and I didn’t haveenough money to go to school. And my parentscouldn’t afford to send me to school. And theyneeded support. And for those reasons I had to goto work in a garment factory.ILRF: What was your favorite subject in school?Lovely: When I was in school, my favorite subjectwas math.ILRF: Why did you like math?Lovely: Because I used to work in business, that iswhy I liked math. When I was five years old—from 5to 11—I sold mouri [a type of fried rice].ILRF: So you went to the factory. How did you applyfor the job?Lovely: I was told by someone that KTS is appointingworkers, so I went there and they asked for myname, my age, and my father’s name, and they didnot ask anything else, and I got the job.ILRF: And when did you start the job?Lovely: I started to work in the garment factory in2006.ILRF: And so then you were 14, or 15, or how oldwere you?Lovely: I was 11 plus years old.ILRF: Why did you decide on KTS? Did you havefamily that worked there? How did you know KTS?Lovely: I decided to get a job in KTS because otherfactories did not appoint workers my age. So onlyKTS was appointing workers my age, child workers.That is why I chose to get a job in KTS.ILRF: What kind of job did you have when you wereat KTS?Lovely: I worked in “Finishing” as a helper.ILRF: What does that mean, what did you do?Lovely: Just helping, packing goods.ILRF: What were you packing? Were they shirts, orpants?Lovely: They were socks.ILRF: Did the whole factory make socks?Lovely: No. I don’t know about the whole building.I can only tell you about the second floor, becauseI used to work on the second floor. And I workedthere for only 23 days. And on the 23rd day, a firebroke out in the factory.ILRF: How many other workers were there with you?Lovely: On my floor, on the second floor where Iused to work, there were about 400 workers.ILRF: What did you think about your job, did you likeit? Did you dislike it?Lovely: I liked my work, what I used to do.ILRF: Why did you like it?Lovely: Because I hadn’t done that job before, and itwas a new job for me. That is why I liked it.ILRF: And so the day that there was the fire, whathappened?Lovely: First the electricity went. Then the factory,they had a generator, so they started the generator.After half an hour, when the electricity came on, theperson who was responsible for the generator didnot switch off the generator. So for that reason, thefire broke out in the factory.Interpreter and Lovely talk.Interpreter: I just asked her, according to theinformation we had, a boiler burst on the groundfloor. She said, she doesn’t know about that.Lovely: The fire took place on the ground floor, andsoon the fire broke out in the factory. The securityguard, he just locked the main gate and went away.So not even one person was able to escape throughthat gate.ILRF: Why did they lock the gate?Lovely: The door had been locked before the firebroke out. The security guard, he went to get teaDEADLY SECRETS5

from a nearby tea store. So, when he saw that thefire broke out on the ground floor, he did not comeback.ILRF: Did you see other people from the factory inthe hospital when you woke up?Lovely: Yes, I saw many of them.Interpreter and Lovely talk.ILRF: What had happened to them?Lovely: Some of them died. And some of themrecovered and went home.Lovely: After the fire broke out on the ground floor,nobody knew upstairs that there was a fire on theground floor. Suddenly we saw that there was somesmoke coming up, but we thought that it was fromanother factory, nearby to our factory. We thoughtthat the smoke was coming from that factory.ILRF: Did the security normally lock the doors?Lovely: Yes. It was normal for the main door of thefactory to be locked, all the time.ILRF: And did they lock the doors between the floorsas well?Lovely: No.ILRF: Did they lock the doors because they didn’twant you to leave?Lovely: I think that they used to lock the doors allthe time because most of the workers were my age,and they thought that we might leave the factoryany time, as we were kids. That is why they alwayslocked the main door.ILRF: So then, what happened, you saw smoke andthen what?Lovely: When we saw the smoke, and after moresmoke came, then, along with the other workers,we tried to escape by way of the stairs. I fell downbecause somebody pushed me. I don’t know whathappened afterwards.ILRF: Why were they pushing?Lovely: Everyone was hurrying to go because therewas a fire, so everyone was in such a hurry. I don’tthink they pushed me intentionally, it happenedrandomly, so I just fell down on the stairs.ILRF: Then what happened?Lovely: I don’t know. I cannot remember anything. Ijust remember that after two days, I was conscious ina hospital. I found myself in a hospital. I don’t knowwho took me there.ILRF: Then what happened when you were in thehospital? Did your family come to see you? Did thefactory managers come to see you or talk with you?Lovely: When I was in the hospital, my family, theycame to me, and they were beside me. But, I don’tknow if the management came. They didn’t even askwhere we were. I didn’t see any management.ILRF: What was the year of the fire?Lovely: It was in 2006, in February.ILRF: Since 2006, there have been many otherfactory fires. Why do you think there are so manyfires in Bangladesh, and why are workers being hurtin the fires?Interpreter: She says she doesn’t have any ideaabout that.ILRF: What should have been different in yourfactory when the fire happened? How do we preventworkers from being hurt or dying in fires?Lovely: I think that if they always keep the gatesopen, then even if there is a fire, I don’t feel like somany lives will be injured, like mine.ILRF: Because you were injured, did you receivecompensation, maybe from the factory, or BGMEA[Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers and ExportersAssociation]?Lovely: I haven’t received anything.ILRF: So you worked for 23 days, and then on the23rd day, you were 11 years old, not even 12 yearsold, and now you’re not able to work for the rest ofyour life?Lovely: I can’t do anything.ILRF: What does that mean for your family?Lovely: It’s just that I became a burden for them, sothey mistreat me. It’s like, if they give me food oneDEADLY SECRETS6

day, maybe the next three days I won’t get food,even from my family. So my family is not supportingme either.ILRF: Do you know who was wearing the socks, afteryou made them?Lovely: I don’t have any idea. It might be, I could getsome idea, if I could have had a chance to work afew more days there.Interpreter: See, I can’t do interview [crying]ILRF: What do you think, maybe when you were 11 or10, what did you dream about, what did you want tobe when you grew up?Lovely: I wanted to study as much as I could, and geta good job and support my family, but my wish wasnever fulfilled. I couldn’t do that.ILRF: And so, it’s been maybe five years, right? Doyou still have health problems?Lovely: Many times I have been to the hospitalbecause it was hurting inside. Neither of my parentshad any money, so they borrowed money for mefrom my neighbors and they took me to the hospital.And, see, I cannot move my fingers, so it is alwayslike this. And after the fire, and the injury, I had tolearn, and it was very hard, I had to learn how to eatrice with these hands.others in your family who are still working in thegarment factories. And we are working very hardto try to make sure that no more fires happen inBangladesh.“My family members stillwork in the factory, but notonly for my family, but for allthose who are working in thefactory, on behalf of them, Iwant to say, please keep thefactory a safe place to work. Idon’t want to see anyone elselike me.”--Lovely, who suffered burns in the KTS TextileFactory fire, February 23, 2006, when she was only11 years oldILRF: Maybe people in your family work in thegarment factories, and there are still many unsafefactories. Do you have anything to say maybe to thepeople that run the factories, or that buy from thefactories?Lovely: My family members still work in the factory,but not only for my family, but for all those who areworking in the factory, on behalf of them, I want tosay, please keep the factory a safe place to work. Idon’t want to see anyone else like me.ILRF: Is there anything else you want to say?Lovely: I want to live a normal life, like other girls. ButI can’t do that.ILRF: Thank you very much for travelling all night onthe bus, and for sharing your story. We will shareyour story. We will make sure that people in othercountries know your story and the story of so manyDEADLY SECRETS7

Executive ---------------------------------“The fire alarm: Waved off bymanagers. An exit door: Locked. Thefire extinguishers: Not working andapparently ‘meant just to impress’inspectors and customers. That is thepicture survivors paint of the garmentfactory fire Saturday that killed 112people who were trapped inside orbetter conditions, workers and worker advocatescourageous enough to demand their rights oftenbecome targets of police and security forces. Theymay face arbitrary detentions, arrests and criminalproceedings on the basis of spurious charges, andthey sometimes endure beatings or threats to theirphysical safety. They are silenced.Meanwhile, the brands and retailers collectivelypossess thousands of confidential factory audits thatmay reveal workplace hazards and even imminentthreats to workers’ health and safety. But it seemsthey have chosen to cease business with factories tosafeguard their reputations and brand images ratherthan reveal their deadly secrets and tell workersabout the risks they face. They have kept theirsilence.jumped to their deaths in desperation.”---Associated Press report on the horrors of the fireat Tazreen Fashions, November 24, 2012. It wasBangladesh’s deadliest garment factory fire --------------------------------For many years the dirty secret of the steadilygrowing Bangladeshi garment industry has been itsunderpaid workers, treated as disposable objects.The lowest paid garment workers anywhere in theworld, hundreds of them have died in preventablefactory fires and building collapses during the lasttwo decades, and many more have been injured.After each tragedy, workers have demanded “nomore fires,” but they have not been heard. Brandsand retailers have conducted factory audits, butnot shared the results with government agenciesor workers even to tell them about imminentdangers. The audits are confidential, their ownprivate knowledge of workplace hazards and laborviolations.Herein lies the twin obstacles to a safe and secureworkplace for Bangladeshi garment workers:workers own voices are silenced and companieschoose not to talk openly about what they know.Although Bangladeshi law and codes of conductof global brands and retailers guarantee workers’rights to organize and bargain collectively forUp to this point, U.S. and European corporateinvestment in the Bangladeshi garment industryhas grown steadily over two decades despitewidespread unsafe workplaces. Bangladesh—at thebottom of the global economy in terms of workers’wages—has emerged as the number-two garmentexporter in the world after China. According to anindustry analysis, Bangladesh is expected to tripleits garment exports over the next ten years and maywell surpass China.2Yet, recent media and political attention to lowwages and unsafe conditions in the Bangladeshigarment industry has raised the possibility thatthe low-road path to industry growth has reachedits limit in Bangladesh. Brands have taken theunprecedented step of calling on the Bangladeshigovernment to raise wages for garment workers.3U.S. and European industry associations have openlyspeculated that Bangladeshi security forces may beresponsible for the recent murder of the Bangladeshilabor rights activist, Aminul Islam.4 Bangladeshimedia is abuzz with reports that CEOs of majorapparel brands worry that their own brands maybe tarnished by association with the Bangladeshi“brand,” threatening diminished investment if thelabor rights climate does not improve.5A shared sense of urgency about a growing crisisfor garment workers has created the possibility fora group of unusual allies to begin designing a wayforward in Bangladesh together. Two major apparelDEADLY SECRETS8

companies have recently agreed to join a newworker safety program with Bangladeshi andinternational unions and labor rights groups, theBangladesh Fire and Building Safety Agreement.The program, when widely accepted and fullyimplemented, may spell the end of the deadlysecrets in the industry. It calls for independentfactory inspections, transparent reporting, andgenuine worker participation in monitoring theirown safety. It includes mechanisms for financingfactory improvements. Unlike other corporatefire safety initiatives, this program is not voluntaryor charitable, but a legally binding agreement.Workers will have a means of holding companiesaccountable for workplace safety and obtainingreparation for wrongdoings.The Bangladesh Fire and Building SafetyAgreement may open a path of collaborationtowards better working conditions for Bangladeshigarment workers. But genuine collaborationrequires a new openness in the industry: acommitment to share knowledge that has beenhidden, and to listen to workers who have beenignored. Knowledge about workplace hazardscannot remain in private hands, but must be shared.Worker voices must be valued and respected, andworkers must be active participants in workplacedecisions that affect their livelihood, life, and death.Based on these principles of openness a broadrange of stakeholders who may not be used toworking together can make a determined joint effortthat will ultimately benefit all.Beyond BangladeshThe last word on this report had hardly been writtenbefore the world awoke to the devastating news ofat least 259 workers trapped and killed in a factoryfire on September 11, 2012.6 This fire was not inBangladesh, but in Pakistan, where textile andclothing exports make up about 58% of the country’stotal exports.7 Local trade unions have reported thatWomen mourning a garment worker who was killed in a fire at Ali Enterprises, Karachi, Pakistan, on September 11, 2012.Photo: Akhtar Soomro / ReutersDEADLY SECRETS9

the factory operated illegally, without the requiredregistration. When the fire broke out more than 600workers were trapped on the upper floors of thefour-story building with only one accessible exit.Most doors were locked, reportedly to prevent theft.8There were no fire exits.9 Windows were barred.Surviving workers reported that stairs and doorwayswere blocked with piles of finished merchandise.10On the same day, a shoe factory fire in Pakistankilled an additional 25 workers.11 Just one day afterthe fires in Pakistan, a fire in a Moscow sweatshopkilled 14 Vietnamese immigrants who were trappedbehind a door that was locked and barred with asledgehammer from the outside.12It turns out that garment factory fires have spreadfar beyond Bangladesh. While a global surveyis beyond the scope of this report, a glance atinternational media and reports of labor rights groupsfrom the last decade reveals substantial numbersof reported garment factory fires in several majorgarment producing countries, including India, theworld’s third largest garment exporter, and China, thetop garment exporter.13For example, the Clean Clothes Campaign reportsthat a fire at Shree Jee International, a footwearmanufacturing and export factory in Agra, India, killed43 workers and injured 11 workers on May 24, 2002.The factory produced shoes for UK brands.14According to the The Indian Express, on May 1,2009, at least six workers died and 30 workerswere injured in a fire at the Lakhani Shoe Factory inFaridabad, India.15 Lakhani Shoes is India’s largestexporter of canvas and vulcanized shoes and beachslippers.16China Labor Watch reports that five workers werekilled in a deadly fire on August 29, 2009, at theRegina Miracle Factory, a women’s undergarmentfactory in Shenzhen, China. The group had earlierreported on sweatshop conditions at this factory,which produced for international brands.17 Chinesepress reported at the time of the fire that the ReginaMiracle Factory was part of the world’s largestmanufacturer of women’s undergarments.18In Pakistan alone, we found at least a dozen garmentor shoe factory fires reported in the media since2004.19Consumers, apparel brands and retailers,governments, and everyone else who has a stakein the global apparel industry must now accept andconfront another deadly secret. Factory fires thatkill the workers who make the clothes we wear arenot the product of exceptional circumstances. Theyare not isolated examples of especially greedy ornegligent owners or corrupt government officials.These are not freak accidents that strike like naturaldisasters with nobody responsible, or the result ofother quirky circumstances of far away places thatare beyond our comprehension. Instead, deadlyfires are the inevitable product of an industryfounded on the idea of underpaid and disposableworkers.Along with abundant low-cost apparel, the industryregularly churns out poverty wages, exhaustingworking hours, and abusive working conditions thatgradually rob workers of their health and vitality,and, sometimes, produces dramatic deadly eventslike fires and building collapses. The unhealthyconditions of the everyday life of garment workersare largely invisible in the world of consumers,causing nobody much concern or discomfort, butthe deadly fires sometimes flare up in the media,shocking us out of our acquiescence.Deadly fires are the inevitableproduct of an industryfounded on the idea ofunderpaid and disposableworkers.We must now be open to a different perspectiveon deadly factory fires. The problem of the fires isnot just a Bangladeshi problem, or just a problemof the major garment exporting nations. Instead,the problem lies not very far from home, if home issomewhere among the major apparel consumercenters of the world. Now that the horrors of themost recent deadly fires in Pakistan and BangladeshDEADLY SECRETS10

have jolted our conscience and opened a space foraction towards a safer world for garment workers,everyone concerned should walk through thatopening and seize the opportunity to rethink theindustry.The setting for this report is Bangladesh and thebasis for the proposals for change are the inhumaneconditions of millions of Bangladeshi garmentworkers. But reports based on other settingswould yield the same conclusions, namely, that thebest model for real fire safety in the global apparelindustry is one founded on respect for workers.Real fire safety means workers are free to reporton dangers in their own workplace and have theability to negotiate better conditions; they have avoice that cannot be ignored. It also means that thelarge apparel buyers share their private knowledgeabout workplace hazards with workers and acceptresponsibility for their safety.Real fire safety means workersare free to report on dangersin their own workplace andhave the ability to negotiatebetter conditions; theyhave a voice that cannot beignored. It also means thatthe large apparel buyersshare their private knowledgeof workplace hazardswith workers and acceptresponsibility for their safety.DEADLY SECRETS11

Chapter 1: Garments ofPoverty or Threads -----------------------------------improve.24 Yet, poverty remains stark, especially inthe cities. As of 2009, some 70% of Bangladesh’surban population lived in slums where only one-fifthof households have access to adequate sanitation.25Access to safe drinkable water is deteriorating. Inthe city of Chittagong, the second largest city inBangladesh, more than 17% of households’ water hastested positive for unsafe levels of arsenic.26“The industry is growing so fast nowbut we are failing our garment workers.We can build huge multi-story factoriesbut we can’t ensure they meet basichealth and safety standards.”--Khondaker Golam Moazzem, senior research fellowat the Dhaka-based Center for Policy Dialogue, afterthe fire at That’s It Sportswear, December 14, ---------------------------------Bangladesh is a country endowed with naturalbounty—rich agricultural lands, abundant water withthe world’s largest delta, and substantial reserves ofnatural gas and coal—but it is also one of the world’spoorest and most densely populated countries.Some 156 million people, equivalent to about half theU.S. population, live in an area the size of the stateof Iowa. Half the population lives on less than 1.25 aday, 84% on less than 2 a day.21 While the countryremains largely rural with 45% of Bangladeshisworking in agriculture, rural livelihoods are moretenuous than ever as farmers face frequent naturaldisasters and the growing threat of climate change.As a result, the cities are growing rapidly. Dhaka, thecapital, is expected to become world’s fourth largestcity with 22 million inhabitants by 2025.22 Fifty-fivepercent of the urban population is crowded togetherin only four cities.23According to the World Bank, Bangladesh has madeimpressive economic and social progress in thepast decade, despite frequent natural disasters.Poverty has declined from 49% of the population in2000 to 32% in 2010, life expectancy is up from 65.7years in 2002 to 68.9 years in 2012, and primaryschool enrollment and literacy rates continue toFor children, poverty is a particularly heavy burden.More than nine percent of children in the slums diebefore the age of five, the highest child mortality ratein any urban area in Asia. Nearly 40% of the childrenunder five are chronically malnourished, the thirdhighest rate in world. Only half of primary-schoolage children attend school. In Dhaka, nearly 14%of children between the ages of five to 14 are childlaborers.27 The International Labour Organizationestimates that there are seven million child workersoverall in Bangladesh and that 1.3 million of themwork in hazardous sectors.28Path to growthThe Bangladeshi government has long seenthe export-oriented garment industry asBangladesh’s ticket out of poverty. A few shortyears after independence in 1971, Bangladeshbegan to take steps towards a market economy,encouraging private enterprise and investment anddenationalizing public industries. The private sectorhas developed unevenly, with major portions of thebanking and jute sectors still under governmentcontrol.29 But the Multi-Fiber Agreement (MFA) intextiles and clothing, in effect from 1974 to 2004,gave Bangladesh a chance to develop a garmentexport industry. The MFA placed export limits ongarment producing nations such as Korea, HongKong, China and India, forcing importers to findadditional sourcing locations.According to the Bangladesh Garment Manufacturersand Exporters Association (BGMEA), Bangladesh’sfirst exports of ready-made garments in 1978 wereworth 12,000.30 The ready-made garment industryhas grown steadily for more than 30 years. TodayBangladesh is the world’s second largest exporterof apparel with 19.1 billion of exports in 2011-2012.31DEADLY SECRETS12

Orders from western brands and retailers, suchas Walmart, H&M, JC Penney, Zara, Tesco, Gap,Kohl’s, Marks and Spencer, G-Star, and Li & Fungflood into Bangladesh’s low-cost garment sectorat ever increasing rates. The ready-made garmentindustry now accounts for 13% of the country’s grossdomestic product and over 78% of total exports with5,000 factories employing 3.6 million workers.32Indirect employment is estimated at around 10 millionpeople.33 Some 59% of Bangladesh’s garmentexports go to the European Union, 26% to the U.S.,and 5% to Canada.34Orders from western brandsand retailers, such asWalmart, H&M, JC Penney,Zara, Tesco, Gap, Kohl’s,Marks and Spencer, G-Star,and Li & Fung flood intoBangladesh’s low-costgarment sector at everincreasing rates.Most analysts and observers believe substantialadditional growth is likely. According to a WorldBank analysis, future growth will be driven bylarger demand for lower cost garments in theU.S. and European markets.35 Apparel makers inBangladesh expect to reach the 30 billion exportmark within the next three years.36 Major apparelretailers and brands also expect continued growthof the Bangladeshi ready-made garment sector. AMcKinsey & Company survey of U.S. and Europeanchief purchasing officers of apparel companies thattogether represent 66% of total Bangladeshi exportsto the U.S. and Europe shows that leading apparelcompanies expect to decrease production in Chinaand increase production in Bangladesh in the nextfive years.The reason for decreasing sourcing in China, saysLi & Fung, one of Walmart’s top suppliers, is thatwages for Chinese garment workers rose by 40%in 2010 and up to 30% in 2011, and that Chinesegarments may be 15% more expensive in 2012compared to 2011.37 Bangladesh, with the region’syoungest and cheapest labor force, a huge capacitywith 5,000 factories, and long-term experience inthe sector, is ideally positioned to benefit f

DEADLY SECRETS 5 two brothers, and I have my parents. ILRF: And are you the oldest, or the middle or the youngest? Lovely: I'm the second one of five. ILRF: Talk with me about why you went to work in the factory. Lovely: I'm from a poor family, and I didn't have enough money to go to school. And my parents couldn't afford to send me to school.