Transcription

20 Common NursingHome Problems and How To ResolveThemBy Eric CarlsonWITH SUPPORT FROM THE COMMONWEALTH FUND

20 Common Nursing Home Problems— and How to Resolve ThemJustice in Agingwith support from The Commonwealth Fundby Eric M. Carlson, Esq.December 2005Updated July 2015Copyright 2005 by Justice in Aging (formerly known as the NationalSenior Citizens Law Center). You may reproduce, copy, or transmit thismaterial free of charge, without prior notice, and without soliciting ourwritten permission, as long as the material remains intact and Justice inAging is given full attribution as author of the work.

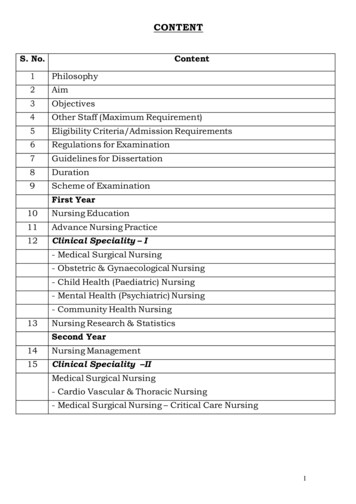

Table of ContentsIntroduction. 5Recommendation: Be a Squeaky Wheel!. 7A Brief Introduction to Medicare & Medicaid. 820 Problems — and How to Resolve Them. 9#1 Discrimination Against Medicaid-Eligible Residents. 9Problems #2–7: Substandard or Inappropriate Care. 10#2 Failing to Take Care Planning Seriously. 10#3 Disregarding Resident Preferences.12#4 Failing to Provide Necessary Services.13#5 Improper Use of Physical Restraints.14#6 Improper Use of Behavior-Modifying Medication.16#7 Excessive Use of Feeding Tubes.17Problem #8: Imposing Visiting Hours on Families and Friends. 18Problems #9–10: Harmful Language in Admission Agreements.19#9 Forcing Family Members and Friends to Take Financial Liability.19#10 Forcing Residents to Give Up Legal Rights and Commit toArbitration. 22Problems #11–14: Losing Medicare Coverage. 24#11 Refusal to Bill Medicare. 24#12 Losing Therapy for Supposed Failure to Make Progress. 26#13 Losing Therapy After Medicare Payment Has Ended. 27#14 Forced Transfer within Nursing Home After Medicare Payment Ends. 28Problem #15: Refusal to Accept Medicaid. 30Justice in Aging www.justiceinaging.org 3

Problem #16: Refusal to Readmit from Hospital. 31Problem #17: Excessive Charges. 32Problem #18: Refusal to Support Resident and Family Councils. 33Problems #19–20: Eviction. 34#19 Eviction Threatened For Being ‘Difficult’. 34#20 Eviction Threatened For Refusing Medical Treatment. 36Concluding Thoughts. 37Justice in Aging www.justiceinaging.org 4

IntroductionThe average consumer knows muchmore about cars (or apartments, or cellphones) than she knows about nursinghomes. What if, for example, an apartment tenant is told by her landlord thatshe has to move out within 48 hours,because she is too “difficult”? The tenantlikely will object, and the law will be onher side in most cases, assuming that therent has been paid.As is explained in the discussion ofProblem #19, being “difficult” never isenough to justify eviction from a nursinghome, and evictions from nursing homesgenerally require 30-day advance notice.These eviction rules are set by the federalNursing Home Reform Law, and theyapply across the country.Unfortunately, however, if a nursinghome resident is told by the nursinghome that she must leave within 48hours on account of being “difficult,”the resident may panic and move out.Because she is unfamiliar with the relevant law, she is inclined to automaticallybelieve everything told to her by thenursing home.Too frequently, nursing homes followstandard operating procedures thatviolate the Nursing Home Reform Lawand are harmful to residents. This guidediscusses some of the most commonpractices, which are actually illegal, andexplains strategies that residents andfamily members can use to avoid orreverse these illegal procedures. The goalis for each resident to receive the bestcare possible in full accordance with thelaw.Important NoteThis guide is not a substitute for theindependent judgment and skills ofan attorney or other professional.If you require legal or other expertadvice, please consult a competentprofessional in your geographic area.The Nursing Home Reform Law,referred to above, applies to every nursinghome that is certified to accept paymentfrom the Medicare or Medicaid programs(or both), even if the resident involved isnot eligible for either program and as aresult is paying privately. Because Medicare and Medicaid are important sourcesof payment, over 95 percent of nursinghomes are governed by the Reform Law.The Reform Law's cornerstone is therequirement that each nursing homeprovide the care that a resident needsto reach his or her highest practicablelevel of functioning. (See Section 483.25of Title 42 of the Code of FederalRegulations) Some residents are capableof gaining strength and function; otherresidents are capable of maintaining theircurrent condition. Still other residents atmost may be able to moderate their levelof decline. In all of these situations, thenursing home must provide all necessarycare.In implementing this guide’s strategies,a resident or resident’s family member attimes may benefit from the assistance ofan attorney or other advocate. One goodsource of assistance is the long-term careombudsman program. Each state hasJustice in Aging www.justiceinaging.org 5

an ombudsman program that providesadvocacy for nursing home residents freeof charge. Contact information for a particular state’s ombudsman program canbe found at the website of the NationalLong Term Care Ombudsman ResourceCenter at www.ltcombudsman.org.Each state maintains an inspectionagency (often part of the state’s HealthDepartment) that is responsible formonitoring nursing homes’ compliancewith the Reform Law, certifying nursinghomes for participation in Medicareand Medicaid, and issuing state licenses.Each of these agencies will investigate inresponse to a consumer complaint, andcan issue warnings or impose penalties toforce a nursing home to fix a particularviolation.The National Consumer Voicefor Quality Long-Term Care (www.theconsumervoice.org) has manyhelpful publications for nursing homeresidents and their families. The federalgovernment maintains a Nursing HomeCompare website (www.medicare.gov/nursinghomecompare/search.html) thatprovides extensive information on individual nursing homes.Justice in Aging www.justiceinaging.org 6

Recommendation: Be a Squeaky Wheel!Can it really be possible that manynursing homes follow illegal procedures?Regrettably, the answer to this questionis an emphatic “yes,” based on theexperiences of the author, and of otherattorneys and ombudsman programrepresentatives who assist nursing homeresidents.The next question is “How?” Morespecifically, how can it be that so manynursing homes have been allowed todevelop standard procedures that violatethe Nursing Home Reform Law?Certainly part of the answer isconsumers’ unfamiliarity with nursinghomes, specifically with the protectionsprovided by the Reform Law. Anotherpart of the answer is the unwillingnessof residents and their family membersto make complaints to nursing homes,due to shyness and a fear that a nursinghome will retaliate against a resident insome way. Together, this shyness, lack ofknowledge, and fear of retaliation allowsome nursing homes to develop andfollow illegal procedures.This guide recommends that residentsand their families develop a healthy senseof entitlement to high-quality nursinghome care. A nursing home is paid thousands of dollars monthly to care for aresident, and is obligated by the ReformLaw to provide individualized care. Aresident or family member shouldn’tfeel sheepish to ask (for example) thatnecessary therapy be provided, or that aresident be allowed to sleep as long as shewants in the morning.While a resident or family membermay be afraid of retaliation, that risk issmall, particularly when compared tothe risk of being passive. Nursing homeemployees generally have no reason orinclination to retaliate. Complaints usually are made to a nursing home’s nursesand administrators, but most day-to-daycare is provided by nurse aides. In anycase, the issues covered in this guide are,in most instances, focused on nursinghome policy and are not directed againsta particular employee.As the cliché counsels, the squeakywheel gets the grease. If a resident andfamily are too afraid or shy to ask foranything, the resident almost assuredlywill get relatively little attention. If,however, a resident and family are determined (but generally polite) in asking forindividualized care, and are appropriatelyfriendly and appreciative, the residentwill tend to receive more attention andbetter care.Justice in Aging www.justiceinaging.org 7

A Brief Introduction toMedicare & MedicaidEligibilityUnder both the Medicare and Medicaidprograms, an adult beneficiary generallymust be at least 65 years old, or disabled.For Medicare coverage, the beneficiaryor beneficiary’s spouse usually must havemade certain contributions through payrolldeductions to the Social Security program.A beneficiary’s income and resources do notmatter. In general, Medicare coverage canbe thought of as a health insurance policypurchased through premiums deductedfrom payroll checks.Under the Medicaid program, a beneficiary need not have contributed to the SocialSecurity program, but must have limitedresources and income. Medicaid moneycomes from both federal and state governments; as a result, some Medicaid rules varyfrom state to state. The Medicaid programcan be thought of as a safety-net health careprogram provided by the federal and stategovernments for persons who otherwisehave inadequate resources to pay medicalbills.Payment for Nursing Home CareThe Medicare and Medicaid programsdiffer in the way that they pay for nursinghome care. Because the Medicaid programis (as described above) a safety-net sourceof payment for individuals who have noother options, Medicaid will pay indefinitelyfor nursing home care, assuming that theresident remains financially eligible andcontinues to need nursing home care.Under Medicaid, the resident might haveto pay a monthly deductible, depending onthe resident’s income and (in some cases)the income of the resident’s spouse. Thename of this monthly deductible variesfrom state to state – for example, “patientpay amount,” “share of cost,” or “Medicaidco-payment.” This guide will use the term“patient pay amount.”The Medicare program, by contrast, paysfor nursing home care for a very limitedperiod of time. At most, Medicare will payfor only 100 days of nursing home care perbenefit period. A new benefit period startswhen the Medicare beneficiary for at least60 days has not received Medicare-coveredinpatient care in the nursing home or in ahospital.Of those 100 days, only the first 20 daysare paid in full. For days 21 through 100,the beneficiary must pay a daily co-paymentof 157.50 (for 2015). Many MedicareSupplement insurance policies (commonlycalled “Medigap” policies) will cover thisco-payment.The Medicare program can pay for nursing home care only if the resident is enteringthe nursing home within 30 days after ahospital stay of at least three nights. Theneed for nursing home care must be relatedto the medical care received in the hospital.Finally – and this is the biggest limitationof all – Medicare payment for nursing homecare is only available if the resident requiresskilled nursing services or skilled rehabilitation services on a daily or almost-dailybasis. The need for these skilled services isdiscussed in considerable detail during thisguide’s discussions of Problems #11 and#12.Justice in Aging www.justiceinaging.org 8

20 Problems — and How to Resolve Them#1Discrimination AgainstMedicaid-Eligible ResidentsWhat You Hear: “Medicaid does not pay for the servicethat you want.”The Facts: A Medicaid-eligible resident isentitled to the same level of serviceprovided to any other nursing homeresident.The Nursing Home Reform Law prohibits discrimination based on a resident’sMedicaid eligibility. A nursing home “mustestablish and maintain identical policiesand practices regarding transfer, discharge,and the provision of services required underthe State [Medicaid] plan for all individualsregardless of source of payment.” (Section483.12(c)(1) of Title 42 of the Code ofFederal Regulations [emphasis added])Nursing homes have a love-hate financialrelationship with Medicaid. On one hand,approximately two-thirds of nursing homeresidents are Medicaid-eligible, and theMedicaid program accounts for approximately one-half of nursing homes’ totalrevenues. On the other hand, Medicaidrates tend to be the lowest – lower thanprivate-pay rates, and much lower than therates paid by the Medicare program.What to Do to FightMedicaid DiscriminationA Medicaid-eligible resident should resistany attempt by the nursing home to giveher second-class treatment. She shouldemphasize the federal law (quoted above)that prohibits a nursing home from discriminating against Medicaid-eligible residents.Nursing home staff members are quick toclaim – generally without proof – that thenursing home loses money on each Medicaid-eligible resident. A resident shouldavoid getting drawn into a discussion of thenursing home’s financial status. There is noway to win the argument without a detailedaudit of the nursing home and any relatedcorporations.A better strategy is to assume that thenursing home’s finances are irrelevant as,indeed, they are in this situation. By seekingMedicaid certification, a nursing homepromises the federal and state governmentsthat it will provide Medicaid-eligibleresidents with the care guaranteed by theNursing Home Reform Law. It is completely hypocritical for the nursing home toaccept Medicaid money for a resident’s care,and then turn around and tell the residentthat the care will be inadequate becauseMedicaid payment rates are low.Justice in Aging www.justiceinaging.org 9

If a nursing home feels that Medicaidrates truly are too low, then it should cancelits Medicaid certification. Otherwise, thenursing home should provide Medicaideligible residents with the high-quality carerequired by the Nursing Home Reform Law.Problems #2–7: Substandard or Inappropriate Care#2Failing to Take Care Planning SeriouslyWhat You Hear: The Facts: “The nursing staff will determine the carethat you receive.”The resident and resident’s familyhave the right to participate indeveloping the resident’s care plan.A nursing home must complete a fullassessment of a resident’s condition within14 days after admission, and thereafter atleast once every 12 months and after a significant change in the resident’s condition.More limited assessments must be done atleast once every three months. Assessmentsuse a standardized document called theMinimum Data Set (“MDS”).Assessments are used for development ofa comprehensive care plan, which must beprepared initially within seven days aftercompletion of the first full assessment. Everythree months, care plans must be reviewedand, if necessary, revised. Also, a care plancan be reviewed and revised at any time asnecessary.The care plan is prepared by a team thatincludes the resident’s doctor, a registerednurse, and other appropriate nursing homestaff members. Most importantly, the teamshould include the resident, the resident’slegal representative, and/or a member of theresident’s family. (See Section 483.20(k)(2)of Title 42 of the Code of Federal Regula-tions) The nursing home staff is required toschedule care plan meetings at a time thatallows others to attend.What to Do to Ensurea Good Care PlanThe resident or family member shouldattend all care plan meetings. (In this discussion, “family member” includes the resident’s legal representative.) If the nursinghome fails to give notice of the meetings,the resident or family member should askwhen the meetings are being held, andrequest to be included.Care planning should be taken seriously.An individualized care plan can be aninvaluable tool to improve the care providedto a resident.Prior to a care plan meeting, the residentor family member should think creativelyabout what the resident might want orappreciate. There is no reason to be timid.A nursing home is paid thousands ofJustice in Aging www.justiceinaging.org 10

dollars monthly to care for a resident, andshould be expected to provide personalizedcare. Also, the Reform Law requires that anursing home address a resident’s particularneeds and preferences. (See Problem #3 formore information.)Some nursing homes treat care plans asa meaningless formality, resulting in careplans that are almost identical from oneresident to the next. This is a great waste ofthe care planning process. To be meaningful,a care plan truly should address individualneeds and preferences.A resident or family member often feelsintimidated by care planning meetings.“Who am I,” a family member might think,“to tell a nurse what should be done for mydad in a nursing home?” The sense of intimidation or shyness is only intensified by thefact that, in a care plan meeting, a residentor family member is likely to be outnumbered by nursing home staff members.The resident or family member shouldresist any sense of intimidation. In mostcases, care planning decisions do not involvecomplicated medical issues. Instead, theoptimal plan of care is relatively obvious,and the issue is whether or not the nursinghome will commit to providing that type ofcare.So, the resident or family member shouldnot feel limited to a one-size-fits-all careplan presented by the nursing home. Theresident or family member should think ofwhat the resident needs or prefers, and askthat that service be written into the careplan.Once the care plan is in place, the resident or family member can use it as neededto assure that the resident receives the bestpossible care. Assume for example that thecare plan calls for the resident to be walkedaround the block daily, but the nursinghome fails to make a staff member availableto assist the resident. In such a case, theresident or family member can point to thecare plan as a requirement that the nursinghome provide the resident with the necessary assistance.Justice in Aging www.justiceinaging.org 11

#3Disregarding Resident PreferencesWhat You Hear:The Facts: “We don’t have enough staff to accommodate individual schedules. You must wakeup every morning at 6 a.m.” “Because of our scheduling, your bathalways will be at 2 p.m.” “If you don’t like the meal entrée, youronly option is a peanut butter sandwich.” A nursing home must makereasonable adjustments to honorresident needs and preferences.Freedom of choice is a vital part of aresident’s quality of life. A nursing homeshould feel like a home rather than a healthcare assembly line.Accordingly, the Nursing Home ReformLaw requires a nursing home to make reasonable adjustments to meet resident needsand preferences. For example, a resident hasthe right to “[c]hoose activities, schedules,and health care consistent with his or herinterests, assessments, and plans of care.”(Section 483.15(b)(1) of Title 42 of theCode of Federal Regulations)The resident or resident’s representativeshould not feel bound by a nursing home’sstandard operating procedures. It doesnot necessarily matter that up to now thenursing home never has allowed residentsto sleep past 6 a.m., or has refused to serveChinese food (for example). If a requestedchange in procedure is reasonable, the nursing home must make the change.Of course, the 64 million question is“What is reasonable?,” but this question hasno scientific answer. Because the definitionof “reasonable” is not precise, residents andfamily members must be prepared to explainwhy the benefit from a proposed change isworth whatever inconvenience or expensemay be involved.More enlightened nursing homes are realizing the benefits – both to residents and tothe nursing homes – of giving more controlto residents and to individual staff members. The goal is to change the culture ofnursing homes so that care is more “residentcentered.” By implementing this “culturechange,” nursing homes across the countryhave improved resident care and customersatisfaction, and have done so while makinga profit. The message to nursing homes is:“Good care is good business.”Helpful information about nursing homeculture change and resident-centered care isavailable from the Pioneer Network, www.pioneeernetwork.net.Justice in Aging www.justiceinaging.org 12

What to Do to Have ResidentPreferences HonoredAs is true throughout the problems discussedin this guide, a resident or resident’s representative should not be hesitant about making arequest to the nursing home. The nursing homeis paid to care for each resident, and there arelegal and moral reasons why each resident isentitled to be treated as an individual humanbeing.Letting a resident sleep past 6 a.m. is easilysupportable, because most observers wouldunderstand why an adult would not want tobe awakened every single day at the crack ofdawn. The nursing home could adjust its nurseaide schedules or, if necessary, increase its nurseaide staffing. A very late-waking resident could#4be served cereal and fruit rather than a hotbreakfast.In requesting a change, the resident orresident’s representative should explain whythe change would be good for the resident,and why the law requires such a change. Afollow-up letter is helpful, as is a copy of thisguide. Oftentimes, the request for a change canbe made in a care planning meeting.A resident council or family council (seeProblem #18) can be a good place in whichto organize support for a change in a nursinghome’s procedures, and specifically for care thatis more resident centered. There is strength innumbers: if an entire group of residents and/or family members is pushing for a particularaction, the nursing home is much more likelyto give in.Failing to Provide Necessary ServicesWhat You Hear: “We don’t have enough staff. You shouldhire your own private-duty aide.”The Facts: A nursing home must provide allnecessary care.The foundation of the Nursing HomeReform Law is the previously discussed requirement that each nursing home provide the carethat a resident needs to reach the highest practicable level of functioning. (See Section 483.25of Title 42 of the Code of Federal Regulations)Obviously, that requirement is being violated ifthe nursing home is expecting or encouragingthe hiring of private-duty aides.What to Do to EnsureAll Necessary ServicesAre Being ProvidedThe resident or family member should makeclear that it is the nursing home’s legal responsibility to provide necessary care, and that aclaimed shortage of staff or money is no excuse.The specific request should be made in writingand, if necessary, the relevant law and/or a copyJustice in Aging www.justiceinaging.org 13

of this guide can be included as support.The need for the specific care might beshown by such documents as a doctor’sorder, the assessment, and/or the care plan.If the nursing home continues to refuseto provide necessary care, a complaint can#5be made to the state inspection agency (seeIntroduction). Other options include raisingthe issue at a resident or family councilmeeting (see Problem #18), seeking assistance from the long-term care ombudsmanprogram (see Introduction), or consultingwith an attorney.Improper Use of Physical RestraintsWhat You Hear: The Facts: “If we don’t tie your father into his chairhe may fall or wander away from thenursing home. There’s just no way we canalways be watching him.”Physical restraints cannot be usedfor the nursing home’s convenienceor as a form of discipline.A physical restraint is a device thatrestricts a resident’s freedom of movement.Perhaps the most common physical restraintis a vest or belt that ties the resident into hiswheelchair or bed. A seat belt is a physicalrestraint, as is a chair that is angled back toprevent the resident from standing up. Bedrails are another common type of physicalrestraint.Under the Nursing Home Reform Law,a physical restraint can be utilized onlyto treat a resident’s medical conditions orsymptoms. Restraints never can be usedfor discipline or the nursing home’s convenience. (See Section 483.13(a) of Title 42 ofthe Code of Federal Regulations)The use of physical restraints has droppeddrastically over the past twenty yearsand many nursing homes now functioncompletely restraint-free. Part of thisdecline certainly is due to the Reform Law’srestriction on the use of physical restraints.Another part of the decline is due to agrowing medical consensus that, instead ofprotecting residents, the use of restraints isharmful, both physically and psychologically. By limiting a resident’s ability to move,restraints may cause a resident to becomeever more unsteady, and more susceptibleto falls and injuries. Some residents areasphyxiated and die after becoming tangledup in restraints. Psychological consequencescan be equally devastating.Like any type of medical intervention,physical restraints can be used only with theconsent of the resident or, if the residentdoes not have the mental capacity toconsent, the resident’s representative. If theuse of restraints is recommended by theresident’s doctor, the resident or resident’srepresentative has the choice whether toaccept or reject that recommendation, butthat choice should be made with knowledgeof restraints’ negative consequences. Thenursing home must suggest less restrictiveJustice in Aging www.justiceinaging.org 14

methods of managing the problem forwhich restraints are being recommended.What to Do to LimitUse of RestraintsIf the nursing home recommendsrestraints to prevent the resident fromwandering, the resident’s representativeshould just say no. First, of course, the useof restraints requires an order from theresident’s doctor, not just a recommendationfrom the nursing home. Also, in this casethe use of restraints evidently is beingproposed solely for the nursing home’sconvenience. Instead of imposing restraints,the nursing home should explore optionssuch as increasing staffing levels, installingan electronic monitoring system, or havingmeaningful activities available to combatboredom and use up excess energy.What if a resident’s doctor proposes arestraint to prevent the resident from falling– for example, a vest restraint proposed toprevent the resident from slipping from hiswheelchair? Although the restraint likelywill be presented as a means of preventingfalls and injuries, it is important to keep inmind that the restraint instead may causethe resident to become weaker and morevulnerable to injury. In addition, the experience of being tied to a chair may tend tomake the resident agitated or depressed. In aworst-case scenario, the resident becomes sodepressed that he is mute, withdrawn, andslumped over. Also, the use of restraints notinfrequently leads to injury, as an agitatedresident thrashes around in an attempt tofree himself. The worst-case scenario ofphysical injury is that the resident strangleshimself while trying to get loose.Alternatives to restraints always exist,and those alternatives can be effective inprotecting residents’ health and safety. Analternative to bed rails, for example, is abed that can be lowered to just a few inchesfrom the floor, along with a padded matplaced next to the bed.The ultimate decision on the use ofrestraints rests with the resident or (morelikely) the resident’s representative, anddepends on the facts of the particular situation. In making the decision, the resident’srepresentative should make sure that theuse of restraints is a last resort, and shouldbe aware of the considerable research onhow the use of restraints can be limited orvirtually eliminated.If and when restraints are recommended,a resident’s representative may want todiscuss the issues in a care plan meeting. Thecare planning process is a good opportunityto discuss the pros and cons of restraints,and to examine possible alternatives.Justice in Aging www.justiceinaging.org 15

#6Improper Use of Behavior-Modifying MedicationWhat You Hear: “Your mother needs medication in orderto make her more manageable.”The Facts: Medication can be used to modifybehavior only when the behavioris caused by a diagnosed illnessfor which a specific medication isneeded for the resident’s treatment.Under the Reform Law, a behavior-modifying medication – also called a “psychoactive” medication – can be used only totreat a resident’s medical conditions orsymptoms. Behavior-modifying medicationcannot be used for discipline or the nursinghome’s convenience. (See Section 483.13(a)of Title 42 of the Code of Federal Regulations)Like any other medication, behavior-modifying medication can be administered only with the consent of the residentor – if the resident does not have mentalcapacity to consent – the resident’s representative. If behavior-modifying medication isrecomm

ally are made to a nursing home's nurses and administrators, but most day-to-day care is provided by nurse aides. In any case, the issues covered in this guide are, in most instances, focused on nursing home policy and are not directed against a particular employee. As the cliché counsels, the squeaky wheel gets the grease. If a resident and