Transcription

A new—and intriguing—science revealsthe triggers that influence us.By David BerrebyI L L U S T R AT I O N SB Y P E T E R H O R VAT H

TheGentleArtofPersuasion57

TheGentleArtof Persuasionhile staying at a hotelin Montreal recently,Tom Dietz found a card near his sinkthat urged him to use his towels morethan once. It didn’t tell him that reusingtowels was good for the environment orthat it would reduce society’s energy costs (though those areboth good reasons for guests to refold). Instead, it simplyinformed him that most other people were reusing theirtowels, and asked him to “join your fellow guests in helpingto save the environment.”Dietz, a professor of sociology and environmental science and policy at Michigan State University who has longstudied environmentally related behaviors, recognized anidea familiar from lab work and other research: You getpeople to reuse towels by telling them that’s what mostpeople do. The study showing this had been conducted inmore than a thousand hotel rooms across the U.S. in 2003,and it had found that telling guests they could help the environment by saving their towels had caused about a thirdto comply. But telling them that most guests were alreadydoing so caused nearly 45 percent to go along. What struckDietz that evening, though, was not that he was readingabout towels in a social science lab or library. “For the firsttime since I read that study,” he says, “I was staying in ahotel where they actually used the message.”59

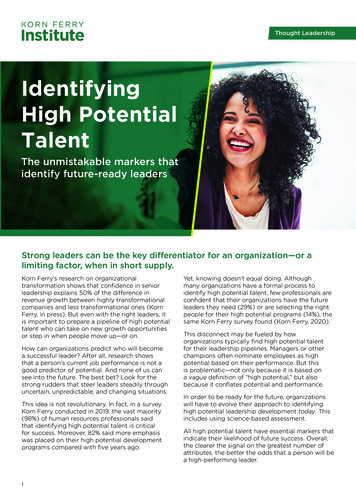

UNDER THEINFLUENCERobert Cialdini, thepsychologist who literallywrote the book on thesubject of influence, hasidentified six drivers thatincline people to go alongwith what others want.They are:Six DriversforPersuasionRECIPROCITYSOCIAL PROOFCOMMITMENT& CONSISTENCYLIKENESSAUTHORITYSCARCITYPeople whofeel they havereceived agift, favor orgood treatment feelimpelled togive back.Handwrittennotes are effective.Many peopleare guided bywhat othersdo—or whatthey thinkothers do.For example:Electricity bills thatcompare yourneighbors’usage.People willdo things toavoid feelingthey have notkept theirword or because they’vedone it in thepast. Remindstudentsthey’re supposed to behonest andthey’ll cheatless.Any kindof sense ofsimilaritymakes peopleinclined to favor or cooperate well witheach other,including similar names andeven similarSocial Security numbers.People trustauthority. In asense we haveto. We don’thave the timeor energy tofigure out everything fromtraffic lawsto weddingplanning forourselves.People willbe eager tohave whatappears hardto obtain. Ifthey thinksomething israre or hardto get, theywill chase it.

For example, thanks to the new discipline ofbehavioral economics, which tracks how peoplemake often-irrational choices, governments arebuilding policies that rely on our biases and rough,often inaccurate, rules of thumb. They’re oftenknown as “nudges,” the term coined for them bythe economist Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein,the law professor and former chief of the WhiteHouse’s Office of Information and RegulatoryAffairs. (“Nudge” policies are in place in 136 out ofthe world’s 196 nations, according to a recent studyby Mark Whitehead, a geographer at AberystwythUniversity in Wales.) At the same time, businesseshave turned to similar techniques to deal withemployees and customers.Today, as a tool for persuading people to dothings, “behavioral science is in a kind of GoldenAge,” writes Cialdini, the Regents’ ProfessorEmeritus of Psychology and Marketing at ArizonaState University, in his latest book, “Pre-Suasion: ARevolutionary Way to Influence and Persuade.”Cialdini, who styles himself “the Godfather ofinfluence,” is one of the main drivers of this trend.Like the “nudge” approach, Cialdini’s begins byaccepting that people’s decisions often are notrational. But nudges often work outside people’sawareness, Dietz notes: You can be nudged intoa 401(k) plan without knowingthat was what happened. His 1984book “Influence” introduced theidea of non-explicit persuasionto millions. To map “the factorsthat cause one person to say yes toanother person,” he says, he spentthree years shadowing “compliance professionals”, who sold thepublic on everything from cars totelevisions to stock. From that, hedistilled the basic principles thatmade people susceptible to pitches.Not incidentally, it was Cialdiniand his colleagues who devised thetowel study. The towel-recyclingpitch appeals to “social proof,” oneof the six principles named in “Influence.” The fact that a lot of usare doing something is a powerfulmotivator for us to do the same.If we were thinking about itPeople aroundthe world areencounteringfewer pitchesaimed at theirpocketbooks andmore aimed attheir psyches. Thepersuasive magicthat once belongedto self-mademasters is turninginto a science.61TheGentleArtof PersuasionThe new science ofpersuasion—which showshow subtle, often unnoticed,cues can drive people morethan facts, arguments, quantifiable carrots (like bonuses)and sticks (like fines)—has gone mainstream. It’smaking itself felt in organizations large and small,and in government as well.If you have received a letter from your powercompany or local water authority telling you howyour use of their product compares with yourneighbors’; or found yourself asked to commit publicly to a goal (like weight loss or quitting tobacco);or noticed calorie information on a restaurantmenu; or just shopped for a mattress on a websitewhose background image was of fluffy clouds, thenyou too have felt it.Today, says psychologist Robert Cialdini, socialscientists have figured out the workings of the mindinto which persuasive pitches fit like a key in a lock.It is now, he argues, “possible to learn scientificallyestablished techniques that allow any of us to bemore influential” than we are when we use onlyfacts and figures. We can, he says, “front-load theseprinciples and motives in people, so that when theyencounter our evidence, they’re ready to see it.”Not long ago, governments andbusinesses assumed that peoplewere rational—or that at least theyhad to treat people as if they wererational—because they didn’t havean alternative model. Experts atpersuasion (the top salesman, thegenius copywriter) followed theirinstincts and couldn’t entirelyexplain how they did it. And whenan organization assumes peopleare calculating their decisionsrationally, Dietz notes, “then to getpeople to change, it’ll try to changeincentives, which usually meansprices.” Today, though, peoplearound the world are encounteringfewer pitches aimed at their pocketbooks and more aimed at theirpsyches. The persuasive magic thatonce belonged to self-made mastersis turning into a science.

Apparentlyinsignificant orunnoticed aspectsof a situation canlead people to leantoward a “yes”before they hearany detail of arequest.consciously, we might express this as “if we’re alldoing that, it must be the right thing for us to do.”But the key is that in general we don’t think aboutit. The mechanism of social proof is a precursorto thinking about it—an automatic response that,in many circumstances, saves time and effort. AsDietz puts it, we like to be in line with “what peoplewe care about are doing.” It works for towels, andit works for many other behaviors. For example,Dutch high school students ate 35 percent morefruit at lunch after they were repeatedly told thatthe majority of high school students make an effortto eat fruit for their health. And in India and Indonesia, companies that were shown to be heavierpolluters than their peers have cut their emissionsby some 30 percent.Cialdini identified six principles of persuasion(see “Under the Influence: Six Drivers for Persuasion”). Lately, Cialdini says, he has found a seventhprinciple hiding all this time in his data: sharedidentity (if a persuader feels like she is “one of us,”we’re more receptive to her message).Cialdini has come to think that there is a secondchannel of persuasion that is even harder to resistthan the influence factors he has been describingsince the 1980s. It exists before the pitch even starts,when apparently insignificant or unnoticed aspectsof a situation can lead people to lean toward a “yes”before they hear any detail of a request. In otherwords, the seven principles don’t just operate withinpitches—they also operate before the communicationeven starts. Cialdini dubs the effect “pre-suasion.”Pre-suasion, he says, is the creation of a moment,before the pitch, that inclines the “targets” to favorwhat they are about to hear. In creating those moments, the principles apply. “The factor most likelyto determine a person’s choice in a situation is oftennot the one that offers the most accurate or usefulcounsel; instead, it is the one that has been elevatedto attention [ ] at the moment of decision.” Makesomeone feel they should reciprocate in this “privileged moment,” and they’ll be inclined to do so when,in the next, they hear your message. Make someoneworry that something is scarce, and they’ll be readyto receive such a message. Recently, for example,Cialdini was in a big-box store browsing for a possible television purchase but not planning on buyinganything. While eyeing a particular TV, a salespersontold him that there was only one set left at that price,“and a lady had just called from Scottsdale and she62

The trouble arises when conscious, logicalthought ought to be brought to bear, but peopleare too hurried, sleepy, distracted (or all three) andso rely on their built-in decision-making guides.Many social scientists, Dietz says, have seen thiskind of tunnel vision. As a colleague of his toldhim, “You get called into a room where you’re theonly social scientist, and you get asked, ‘How do weget people to stop doing stupid things?’ And what‘stupid things’ means is ‘not in line with the valuesof the people in the room.’ ”Because it works outside our awareness (andbecause it can be made to work even better bymaking people rushed, sleep deprived and scattered), the new science of persuasion is now thesubject of an ongoing and lively debate among bothscholars and practitioners. Is it ethical to nudgepeople to do something they don’t know you’repromoting? What is the difference between a legitimate tactic for setting up a privileged moment, andcreating an unfair advantage?What if organizations decide they should takeadvantage of the fact that persuasive principles workwell “under the radar”? Cialdini believes, in the longterm, such organizations only harm themselves.Deceptive organizations’employees have lower productivity, more turnover andare more likely to cheat theiremployers, he says. “It’s akind of triple tumor.”Still, the power ofpersuasive science towork “under the radar”means society needs somesafeguards, Dietz says.The only assurance we canhave against abuse is forpeople who are targets ofpersuasion to have a rolein deciding when and howthey will be used. “To whatdegree are people—who aregoing to be affected—empowered to design the process?” he asks. “That’s goingto be a crucial question.” TheGentleArtof Persuasionwas on her way over,” he says. “Ten minutes later I’mwalking out of the store with that television set. Iwrite books on this and it worked on me.”Cialdini was happy with his purchase, becausethe television really was a good deal. These tacticswork best when people don’t reflect, and we oftendon’t notice that they’re being used. “One thingabout pre-suasion is that it almost always fliesunder the radar,” Cialdini says. “People don’t recognize that they’re being influenced.”But of course pre-suasion, and other tools fromthe science of getting people to do what you want,can also be used to steer people toward harm.For example, marketers can create the illusion ofscarcity about a product that isn’t really scarce. Or,like the officials at the British Department of Workand Pensions in 2014, they can create phony socialproof. In that office, all unemployed people who hadtaken a personality test were told they had traitsincluding “love of learning” and “curiosity” and“originality.” People who believe they have thosetraits have been shown to spend less time unemployed. But what people were told had no relationto their real test results. (The test program was discontinued after it was revealed by The Guardian.)

INFLUENCE Robert Cialdini, the psychologist who literally wrote the book on the subject of influence, has identified six drivers that incline people to go along with what others want. They are: RECIPROCITY People who feel they have received a gift, favor or good treat-ment feel impelled to give back. Handwritten notes are ef-fective. SOCIAL PROOF

![No, David! (David Books [Shannon]) E Book](/img/65/no-20david-20david-20books-20shannon-20e-20book.jpg)