Transcription

Identity traps:How to think aboutrace & policingpro p o s a lPhillip Atiba GoffabstractSince the summer of 2014, Americans have seen more videosof violent interactions between police and non-Whitesthan ever before. While the interpretation of some specificincidents remains contentious and data on police use of forceare scant, there is evidence that racial disparities in policingexist even when considering racial disparities in crime. Thetraditional civil rights model of institutional reform assumesthat racial bigotry is the primary cause of these disparities; itattempts to address problems through adversarial litigation,protest, and education. This article offers an expansion ofthat model—one based on insights from behavioral science—that facilitates a less adversarial approach to reform andallows one to be agnostic about the role of racial bigotry.The new behavioral insights model focuses on identifying thecontexts—called identity traps—that can escalate negativeinteractions between police and communities, as well asways to interrupt them.Goff, P. A. (2016). Identity traps: How to think about race & policing. Behavioral Science& Policy, 2(2), pp. 11–22.

RwCore FindingsWhat is the issue?Implicit bias and selfthreats are importantidentity traps that mediatethe relationship betweenlaw enforcement andcommunities. Thetraditional civil rightsmodel of reform shouldtherefore be expandedto include thesebehavioral insights.How can you act?Selected interventionsinclude:1) Creating standardsfor law enforcementdata capture to enablemore robust studies2) Increasing the Bureauof Justice Assistancebudget and linking fundingto evidence-basedprograms or practices3) Disseminating bestpractices and guidanceacross law enforcementdepartments communitiesWho should takethe lead?Policymakers anddecision makers in lawenforcement, behavioralscience researchers12ecent disturbing videos depicting thedeaths of unarmed Black citizens via policeinteractions continue to stoke protestand outrage among communities in Baltimore,Maryland; Oakland, California; and Ferguson,Missouri, to name a few. Many non-Whitesbelieve that, because of their race, they routinelyexperience injustice at the hands of law enforcement. Indeed, people of all colors feel thatracism is likely a fundamental problem in American law enforcement.1To combat racism, many reform-minded citizens have depended on what I call the traditionalcivil rights model (TCRM), which relies on directaction, litigation, and legal sanction. In the caseof policing, this model has meant that peoplehave responded to racism with protests, lawsuits,and calls for federal oversight to address grievances. Although these remain valuable tactics,an adversarial approach can, at times, also havethe unintended consequence of exacerbatingtensions between police and the communitiesthey are sworn to protect. In this article, I presentan expanded—and less antagonistic—model,the behavioral insight model (BIM). It is basedon behavioral science research, and I apply it topolice reform.Taking advantage of the insight that situations are more powerful than attitudes whenpredicting behavior (including racial attitudes such as prejudice), 2–4 the BIM approachinvolves attempting to determine which situations improve and which situations undermineinteractions between police and civilians. Acollateral benefit of this framework is that itallows researchers and advocates to remainagnostic about the intentions and characterof police officers while developing a plan topromote equity. Similarly, with its focus on identifying the mechanisms that produce inequality,the BIM also communicates that doing theright thing merits significant resources. Takentogether, these two messages can help defusethreats to the self-concept that arise whenracism is discussed.5,6 It is important to note thata BIM approach need not sublimate concernswith explicit bigotry nor absolve the need fordirect action and litigation. Rather, it providesan expanded tool kit for addressing contextswhere naked bigotry is insufficient to explainracial disparities.What follows is an introduction to the BIM and itscore scientific elements. The scientific researchon BIM for racial reform revolves around identity traps, the universal psychological tendenciesthat can produce racial injustice or detriment fora group, and procedural justice, the consensusamong behavioral scientists that compliancewith the law is more readily facilitated by trust inthe justice system than fear of it. (See Glossary ofKey Terms.) Finally, having outlined the processand the science on which it is based, I concludewith examples of successful interventions (withcaveats on their limitations) and recommendations for improving both the science and thepractice of police reform.A Model Based on BehavioralScience InsightsThe founder of experimental social psychology,Kurt Lewin, is famous for saying, “There isnothing so practical as a good theory.” Theories orient people to problems, guide strategicthinking, and shape decisionmaking. Forinstance, a theory that a sports team’s losingrecord is the fault of a subpar defense will leadto very different hiring, practice, and salary decisions than will a theory that the subpar offenseis at fault. And so too it is with theories of racialinequality. The belief that racial inequalitystems from the immoral behaviors of Blacksand Latinos leads to different solutions to theproblem than the theory that the racial prejudices of Whites cause racial inequality.The theory that has tacitly undergirded much ofthe work around police reform and racial justiceis the TCRM. This model assumes that raciallydisparate outcomes and bigotry are synonymousand that the solutions to racial inequality, therefore, must engage prejudice.7 If the problem isracial bigotry, then the solution must be education, confrontation, litigation, or a combinationof these strategies.Think about what applying the TCRM might doto a police department that believes it is progressive despite what appear to be racial disparities.behavioral science & policy volume 2 issue 2 2016

Someone embracing a TCRM approach mightaccuse the department of not caring aboutthose disparities or, worse, welcoming them.If these claims are inaccurate, then the TCRMmay alienate an otherwise cooperative department—and likely provoke a powerful identity trapin police officers: the concern with appearingracist.5,6,8 The accusation will also seem unfair—or illegitimate—in the minds of law enforcement,which in turn jeopardizes police participation inthe reform process. And, as Figure 1 illustrates,when the TCRM fails, it can lead to further adversarial entrenchment. This is not to claim that aTCRM approach is never best or suitable. Itoften is. However, the BIM sees racial disparitiesthrough a different lens and adds to the varietyof tools available. As no two situations are thesame, having a diversity of tools is useful forfixing stubborn problems.The BIM is an expansion of the TCRM, not analternative. The BIM is rooted in certain facts:that racial disparities can arise from a variety ofcauses, that situations are often more powerfulpredictors of human behavior than attitudes,and that collaboration is usually preferableto combat. When the BIM is used in policingcontexts, researchers and advocates take thetime to look into the causes of disparities. Thiscommunicates that they take seriously a policedepartment’s desire to reduce racial inequality.By working backward from the disparity withoutan a priori theory about police officers’ character, the BIM allows researchers to assume(either strategically or genuinely) that all actorsinvolved intend to do the morally just thing.If the implementation of the BIM falls short ofreformers’ expectations, then the more testedTCRM approach is still available (see Figure 1). It ismore challenging, however, to move in the otherdirection—from TCRM to BIM—because accusations of ignorance, apathy, and bigotry cannotbe unsaid.Racial Inequity in Procedural Justice& Use of Force by PoliceHow much of a problem are racial disparities in policing? After all, ifone group commits more crimes than another, we should expect thatgroup to experience more negative consequences of the criminaljustice system, right? This expectation, however, does not hold up inthe light of several analyses of police stops,A,B use of force,C,D sentencing,E,F and subsequent employment prospects,G all demonstrating thatthe size of racial disparities across every phase of the criminal justicesystem cannot be fully explained by racial disparities in crime.For instance, in a recent study that my colleagues and I conducted forthe White House and the Austin, Texas, police department, we examined both the frequency and the severity of force used in that city bypolice. By controlling for the level of crime in a given census tract, aswell as other factors such as income, graduation rate, percentage ofowner-occupied homes, and employment, we were able to see thedegree of racial disparities that persisted.C The results demonstratedthat even though both neighborhood crime and poverty were strongpredictors of police force, neither was sufficient to explain increaseduse of force in Black and Latino neighborhoods. This analysis wasconsistent with previous research my colleagues and I conductedacross 12 departments that examined how racial disparities in arrestrates related to racial disparities in the number and severity of policeforce encounters.C There, again, we found that racial disparities inarrests predicted racial disparities in force, but they were not sufficientto explain them completely.This is consistent with other research on use of force that shows asimilar pattern nationwide at the state level.D So although there is stillconsiderable research to be done on the nature of race and policing,the basic question of why racial disparities exist in police outcomescannot be answered with a simple “because of racially disparate crime.”A. Fagan, J. A., Geller, A., Davies, G., & West, V. (2009). Street stops and brokenwindows revisited: The demography and logic of proactive policing in a safe andchanging city. In S. Rice & M. White (Eds.), Race, ethnicity, and policing: New andessential readings (pp. 309–348). New York, NY: New York University Press.B. Geller, A., & Fagan, J. (2010). Pot as pretext: Marijuana, race, and the new disorder inNew York City street policing. Journal of Empirical Legal Studies, 7, 591–633.C. Goff, P. A., Lloyd, T., Geller, A., Raphael, S., & Glaser, J. (2016). The science of justice:Race, arrests, and police use of force. Retrieved from Center for Policing Equitywebsite: 07/CPE SoJ Race- Arrests-UoF 2016-07-08-1130.pdfD. Ross, D. (2015, May 17). 5 ways to jumpstart the release of open dataon policing [Blog post]. Retrieved from ng/E. Mustard, D. B. (2001). Racial, ethnic, and gender disparities in sentencing: Evidencefrom the US federal courts. The Journal of Law and Economics, 44, 285–314.F. Sidanius, J., & Pratto, F. (2004). Social dominance theory: A new synthesis. New York,NY: Psychology Press.G. Pager, D. (2003). The mark of a criminal record. American Journal of Sociology,108, 937–975.Identity Traps: Thinking,Fast & Slow, About RaceSocial psychology research offers two mainsets of literature regarding the mechanisms ofracial bias. Both emphasize situations over attitudes or intentions in explaining racially disparate13outcomes. And, it is important to note, both literatures demonstrate how racial inequality canarise even in the absence of racial bigotry. Thefirst concept, implicit bias, refers to the humanbehavioral science & policy volume 2 issue 2 2016

Figure 1. A conceptual flow chart comparing the traditional civil rights model& the behavioral insight model for addressing racial disparitiesTheory TitleMethods for Changing ProcessTraditionalCivil Rights ModelBehavioralInsight ModelIgnorance,Apathy, and/or BigotryPsychologicalVulnerabilities orSituational FactorsAwareness Raising,Public Shaming,LitigationConstructing anEvidence BaseProcess SuccessIf SuccessfulIf UnsuccessfulIf SuccessfulIf UnsuccessfulOutcomesPublic Pressurefor Change &Successful LegalPrecedentResentment& ResistanceCollaborativePolicy ReformBegin TraditionalCivil Rights Modeltendency to store and retrieve informationabout groups and group members in associatedchunks.9–14 Simply storing information in chunksis not, in itself, bias. If memories did not function this way, it would be difficult to recall linesfor a school play, burdensome to navigate one’scommute to work every day, and impossible toremember the name of anyone encountered at acocktail party. The second concept, self-threats,refers to the social contexts that cause people tobe concerned that they will be negatively stereotyped because of their identity, that their identitywill not be valued, or that they will be deniedmembership in an important identity group.15–18Because the literatures about these two conceptsoften overlap, “implicit biases and self-threats” iscumbersome to say, and I am often asked whatto call the mechanisms of racial inequality thatdo not require prejudice, I refer to both literatures by one name: identity traps. Identity trapsare robust human psychological tendenciestriggered by someone’s identity (our own or14another’s). They can cause people to act inconsistently with their beliefs and often in ways thatdisadvantage already stigmatized groups (again,either one’s own group or another’s). In additionto unifying two research literatures, this termhas the advantage of simultaneously reducingthe emphasis on individual attitudes and foregrounding the importance of the situation.To distinguish between the two literatures, Iborrowed from Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking, Fastand Slow.19 Because implicit bias works quicklyand beneath conscious awareness, I refer to it asa fast trap. And, because people are often awarethat they are experiencing self-threats, they seemthe appropriate analog to a slow trap. Someexamples may make the distinction more clear.Fast Identity TrapsHere’s an example of a fast identity trap. If weregularly see Norwegians playing handball, wewould tend to think of handball as a Norwegianpastime. Because we store trait information (forbehavioral science & policy volume 2 issue 2 2016

“collaboration is usually preferable to combat”example, handball players) alongside categoryinformation (for example, Norwegian), we wouldtend to recall them together and make an automatic—implicit, or unconscious—associationbetween the two. These automatic associationscan influence behaviors ranging from when welook at a person2 to what we see14 and how werespond to her or him.20,21 For instance, in researchby Dovidio and colleagues, implicit anti-Black biasinfluenced the subtle elements of interpersonalcommunication. In one laboratory study, undergraduate students were brought in two at a timeto have a conversation that researchers videotaped. Coders then counted the number of eyeblinks, nervous fidgets, and gaze aversions (thatis, times when one participant wasn’t looking theother in the eye). What they found was that Whitestudents who were higher in implicit bias wereless likely to make eye contact and more likely tolook uncomfortable with Black students—regardless of their explicit values.2Certain situations can promote fast traps, suchas being in a bad mood or mentally taxed,feeling threatened, needing to make a quickdecision, or experiencing unfamiliar circumstances.10,12,22–25 In these situations, people tendto rely on overlearned associations—such aswhen, after a long, frustrating day at the office,you choose the tried-and-true restaurant ratherthan the new one around the corner. But fastidentity traps happen much more quickly than adecision about where to eat.Can training help? In a laboratory simulation study published in Personality and SocialPsychology Bulletin, Sim and her colleaguesfound that, among people who were not usedto making decisions about shooting, exposureto negative stereotypes about Blacks exacerbated the likelihood of “shooting” unarmedBlack targets. 25 However, participants who weretrained not to associate race with criminality(through exposure to a set of pictures in whichrace was uncorrelated with the likelihood of theperson being armed) were not as easily influenced by stereotypes.15It is tempting to view these laboratory successesas promising evidence that fast traps can betrained out of people, yet it is important to resistthat temptation. Analyses of hundreds of thousands of data points suggest that Americans holdautomatic associations between Blacks and negative stereotypes (for example, criminal, dangerous,armed) at high rates and that these associationsare difficult to eliminate.26–28 The success of theSim intervention, as well as successes experienced by others using similar methods, 29 arebetter viewed as interventions that target the situations within which officers encounter suspects.This is because, although researchers are ableto alter behavior in the moment, there is notgood evidence that those changes persist oversignificant periods of time, and the automaticassociations that undergird them are often notmaterially altered. 29–32 Consequently, it may bemore useful to focus racial equality interventionson defusing the traps that situations lay for one’sautomatic associations than on identifying who isor is not “implicitly biased.”Slow Identity TrapsAgain, slow identity traps roughly correspondto self-threats, which are threats to a person’sconcept of him- or herself. How could a threatto one’s self-concept lead to racially biasedbehavior? Here’s one example.In a series of studies on interactions, socialpsychologists found that Whites who weregearing up to have a conversation with someoneof a different race sat farther away from thatperson when they feared that their racial attitudes might come up,5 and they spontaneouslyworried that they would be stereotyped asracist. 5,8 Further, after having an introductoryconversation with an individual of anotherracial group, both Whites and Blacks reportedconcerns with being stereotyped as prejudiced,and this concern was cognitively taxing.33,34 Thiscognitive depletion can, in turn, lead to subtleforms of bias that disadvantage the stigmatizedgroup by facilitating a reliance on stereotypesfound in fast traps as well as a desire to avoidthose situations altogether.35behavioral science & policy volume 2 issue 2 2016

“procedural justice constitutesa revolution”The literature on self-threats suggests thatthey are most powerful when the threatenedidentity is salient (for example, when peopleare reminded of the identity), 36 when peoplecare about the outcome,16,37 and when peoplebelieve failure might reveal something abouttheir character.5,38–40 The problem is that somesituations threaten many people to the detrimentof vulnerable groups (for example, Blacks). Forinstance, worrying about being seen as racistcan cause Whites to avoid looking at Blacks41 andeven harbor more racist attitudes.42It is easy to imagine how these laboratory resultscould prove disastrous in police–communityinteractions. For instance, in the current climateof concern among many citizens regardingpolice legitimacy, officers patrolling majorityBlack neighborhoods—regardless of their ownrace—may fear being seen as racist. This could,in turn, provoke a relative retreat from proactivecommunity engagement and an increased reliance on racial stereotypes through fast traps.Obviously, none of these possibilities bode wellfor police–community relations. Also notable,however, is that these can happen even when anindividual officer is not bigoted.Procedural JusticeWithin the last three decades, behavioral scienceresearch on the concept of procedural justicehas significantly advanced understanding of howthe mind interprets fairness in policing contexts.The Final Report of the President’s Task Force on21st Century Policing asserts the following:Decades of research and practicesupport the premise that people aremore likely to obey the law when theybelieve that those who are enforcingit have authority that is perceived aslegitimate. . . . The public conferslegitimacy only on those whom theybelieve are acting in procedurally justways. In addition, law enforcementcannot build community trust if it is16seen as an occupying force coming infrom outside to impose control on thecommunity.43It may at first seem that the insights of proceduraljustice are obvious: Treat people fairly and theyare more likely to comply with an officer’s lawfulrequest. Respect someone’s dignity and she orhe will return that respect. Threaten someone, onthe other hand, and he or she will act to defendthemselves against you. Yet, in a criminal justicesystem long governed by deterrence theory—thenotion that threats of harsh punishments are thebest way to deter crime44–47—procedural justiceconstitutes a revolution.Indeed, for those who believe that force bestprotects communities, it may seem laughable tosuggest that preserving citizens’ dignity is moreimportant. But research confirms that concernsabout fair treatment trump the threat of sanction in producing compliance with the law.48,49Issues of procedural justice are more powerfulthan the fear of punishment in predicting criminal behavior,50 compliance with police,51–53 andreporting crime. 54,55 When officers are trainedto communicate the reason for a contact,provide residents with a voice in their outcomes,and ensure equitable treatment, this actuallyimproves outcomes.54,56,57In two large surveys of New York City residents,Sunshine and Tyler of Yale Law School testedwhether concerns with fair treatment were abigger, a smaller, or an equal predictor of intentions to cooperate with the law. In samplestaken before and after the events of September11, 2001, and for both Black and White respondents, the perception that police treat peoplefairly rather than the fear of getting caught wasthe primary driver of an intention to cooperatewith the police.52Given that large and robust racial differencesexist in the perceptions of procedural justicein policing, 58–61 it stands to reason that raciallydisparate gains can be made by improvinga department’s procedural fairness. Again,this need not implicate the racial attitudesof individual officers nor those of an entiredepartment. Rather, where procedural justicebehavioral science & policy volume 2 issue 2 2016

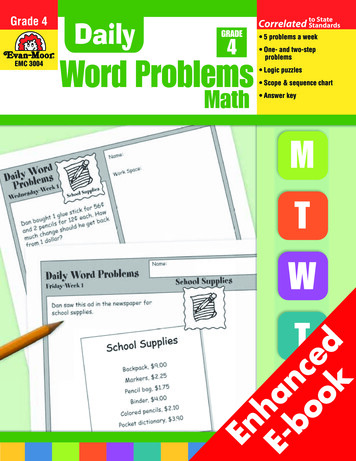

is a newly popular concept in the professionof policing, a cultural shift in police philosophy may accomplish a great deal to improvecommunity trust.62Identity Traps in PolicingThe concepts of identity traps and proceduraljustice are highly relevant to officers’ day-to-dayexperiences. Line officers frequently multitask.63They engage the neighborhoods most vulnerable to crime and violence.64,65 They are oftenasked to do so while working odd hours66,67 andbeing stereotyped as racist.49,68 Their uniformsare a constant reminder of their police identity.And they are tasked with making high-stakes,split-second decisions—some that remove libertyand some that end life. A police officer’s dayseems to be the perfect context for promotingbehavior influenced by fast and slow traps. Sohow can a police department defuse them?The Las Vegas Metropolitan Police Department(LVMPD), Queensland (Australia) Police Department, and the President’s Task Force on 21stCentury Policing provide promising examplesand recommendations.Case Study, Las Vegas, Nevada:Defusing the Fast Trap of Foot PursuitsIn 2010, the LVMPD reached out to the Centerfor Policing Equity (CPE), a nonprofit researchand action think tank based at the John JayCollege of Criminal Justice and the Universityof California, Los Angeles. The LVMPD askedCPE, where I serve as cofounder and president, to conduct research that would determinewhether it showed a pattern of excessive use offorce that would be considered racially disparate based on the distribution of force in thecity. Before CPE’s formal analyses began, it wasdiscovered that a high percentage of use-offorce incidents occurred immediately after footpursuits. Although good data on foot pursuitswere lacking (the LVMPD did not begin collectingfoot pursuit data until 2014), these chases werestill deemed an ideal context in which to gatherevidence because of the nature of the contact.For anyone familiar with police serial dramas, itmay seem as if foot pursuits are high-adrenalinechases that end when an officer springs on the17suspect, tackling the runner to the ground (and,potentially, moaning that he or she is “getting tooold for this”). However, although foot pursuitsare indeed high-adrenaline events, they do nottend to end via police tackle. Rather, the bulk offoot pursuits stop when the suspect realizes heor she is surrounded and gives up. Yet, if asked,“How do most foot pursuits end?” a police officer’s most likely response will be, “With the useof necessary force to subdue the subject.”Recall that depletion, time pressure, high stakes,and limited resources are all likely to exacerbateidentity traps. Consequently, CPE used the BIMtheory of change to recommend a revised policyto the LVMPD: whenever possible, the officer inthe foot pursuit is not permitted to be the firstperson to lay hands on the subject if the subjecthas surrendered and is not deemed to be animmediate danger to him- or herself or others.Adjusting the situation so that the officers experiencing an adrenaline-pumping chase were notthe ones to “go hands on” with a possible criminal should help prevent police from succumbingto identity traps.The policy went into place at the end of 2011.Figure 2 reveals that the LVMPD experienced a23% drop in use-of-force incidents and a furtherdecline the following year. However, the data didnot look at foot pursuits in particular. Becausethe department did not keep foot pursuit statistics and because of other simultaneous policychanges, it is unwise to make a strong causalstatement about the effects of this intervention. Still, although this is far from a randomizedexperiment, both the LVMPD and Departmentof Justice (DOJ) believe the interventions werecentral enough to these declines in force thatthey feature prominently in the DOJ report onthe progress the LVMPD has made in keepingthe department out of a federal consent decree,the tool that the DOJ uses to compel departments to reform.69 In addition, more than 10major police departments, including those inLos Angeles, Seattle, and St. Louis County, havevisited the LVMPD with the aim of adoptingthis program (among others). It is critical thatadditional rigorous research be run to test thepotential benefits of this intervention.23%drop in use-of-forceincidents experienced bythe LVPD after pilotingbehavioral interventions 14mamount set aside bythe Laura and JohnArnold Foundation forrandomized controlledexperiments in policingthe National JusticeDatabase is the largestUS effort to collect,standardize, and analysedata on police behaviorbehavioral science & policy volume 2 issue 2 2016

Number of Nondeadly Use-of-Force Incidentsper Year in LVMPDFigure 2. Number of nondeadly use-of-force incidentsper year in the Las Vegas Metropolitan Police Department(LVMPD), 2010–20131,2001,0901,000Unfortunately, this study is among the fewrandomized field tests of procedural justicein policing. So, although research exists thatsupports the claim that procedural justice worksin the field, both the laboratory and the surveystudies would benefit from significantly moreevidence on generalizability and boundaryconditions. For instance, because Black Americans are far more likely to experience contactwith police, would similar interventions be moreor less powerful in improving perceptions of lawenforcement in those The Intersection of Policy & ResearchIntervention in late 2011/early 2012Source: Data are from Collaborative Reform Model: Final Assessment Report of the LasVegas Metropolitan Police Department, by G. Fachner and S. Carter, 2014, Washington, DC:Community Oriented Policing Services. Copyright 2014 by CAN.Case Study, Queensland, Australia:Trust Breeds ComplianceTo demonstrate the benefit of procedural justicein improving compliance with the law and theperceived legitimacy of a police action, Mazerolle and her colleagues convinced a policedepartment in Queensland, Australia, to workwith them on a randomized, controlled study.70,71Mazerolle, who is an Australian Research CouncilLaureate Fellow, and her research team randomlyassigned officers at random breath tests (roadblocks to screen for intoxicated driving) toconduct business-as-usual stops or to readfrom a treatment script designed to communicate the tenets of procedural justice duringa stop (community voice, respect, neutrality,and trustworthiness). Drivers were then givena survey about procedural justice and theirintended compliance with police. Drivers whoreceived the procedural justice script reportedthat the stop was more legitimate than did thosesubjected to the business-as-usual stop. Moreover, the procedural justice script drivers felt thepolice department itself was more legitimate and18these factors, in turn, predicted their intendedfuture compliance with police. In other words,fair treatment improved perceptions of aspecific stop and of the police in general; it alsopromoted future police compliance.President Obama’s Task Force on 21st CenturyPolicing provided a series of recommendationsdesigned to advance public safety. Although therecommendations are not binding and a changein administration likely means a pivot in the federalagencies’ priorities, the task force recommendations still constitute a road map for reducingracial disparities. Many of those

Fast & Slow, About Race Social psychology research offers two main sets of literature regarding the mechanisms of racial bias. Both emphasize situations over atti-tudes or intentions in explaining racially disparate outcomes. And, it is important to note,