Transcription

Brühl et al. BMC Psychiatry(2019) EARCH ARTICLEOpen AccessChild maltreatment, peer victimization, andsocial anxiety in adulthood: a crosssectional study in a treatment-seekingsampleAntonia Brühl1,2* , Hanna Kley3, Anja Grocholewski2, Frank Neuner3 and Nina Heinrichs1,2AbstractBackground: Childhood adversities, especially emotional abuse, emotional neglect, and peer victimization areconsidered to be crucial risk factors for social anxiety disorder (SAD). We investigated whether particular forms ofretrospectively recalled childhood adversities are specifically associated with SAD in adulthood or whether we findsimilar links in other anxiety or depressive disorders.Methods: Prevalences of adversities assessed with the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ) and a questionnaireof stressful social experiences (FBS) were determined in N 1091 outpatients. Adversity severities among patientswith SAD only (n 25), specific phobia only (n 18), and generalized anxiety disorder only (n 19) were compared.Differences between patients with anxiety disorders only (n 62) and depressive disorders only (n 239) as well asbetween SAD with comorbid depressive disorders (n 143) and SAD only were tested.Results: None of the adversity types were found to be specifically associated with SAD and severities did not differamong anxiety disorders but patients with depressive disorders reported more severe emotional abuse, physicalabuse, and sexual abuse than patients with anxiety disorders. SAD patients with a comorbid depressive disorderalso reported more severe adversities across all types compared to SAD only.Conclusion: Findings indicate that particular forms of recalled childhood adversities are not specifically associatedwith SAD in adulthood. Previously established links with SAD may be better explained by comorbid depressivesymptoms.Keywords: Social anxiety, Social phobia, CTQ, Trauma, Child maltreatment, Peer victimizationBackgroundChildhood maltreatment and peer victimization areknown to be crucial risk factors for mental health [1]. Insocial anxiety disorder (SAD), social learning experiencesin childhood and adolescence are an important component of contemporary etiological models [1–3]. Therefore,* Correspondence: bruehl@uni-bremen.deThe authors Antonia Brühl and Nina Heinrichs changed universities and arenow at University of Bremen, Department of Psychology, Clinical Psychologyand Psychotherapy.1Department of Psychology, Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy,University of Bremen, Grazer Strasse 2, 28359 Bremen, Germany2Department of Psychology, Institute of Clinical Psychology, Psychotherapyand Assessment, Outpatient clinic, Technische Universität Braunschweig,Humboldtstr. 33, 38106 Braunschweig, GermanyFull list of author information is available at the end of the articlemany researchers investigated the link between childhoodmaltreatment and SAD and repeatedly showed that exposure to such experiences in childhood are associated withSAD in adulthood [4, 5]. However, comparing resultsacross studies is difficult because a variety of assessmentshave been employed to assess childhood maltreatment.A growing body of research investigated the associationbetween history of childhood maltreatment and SAD byusing the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ) [6],which assesses emotional abuse, physical abuse, sexualabuse, emotional neglect, and physical neglect. These studies linked specific maltreatment types to SAD symptomseverity in individuals with SAD [4, 5, 7, 8] and/or compared histories of child maltreatment between individuals The Author(s). 2019 Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, andreproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link tothe Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication o/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Brühl et al. BMC Psychiatry(2019) 19:418with SAD and non-clinical control groups [5, 9]. Findingsshowed that emotional abuse [5, 9] and emotional neglect[5] were more often reported by subjects suffering fromSAD in comparison with healthy controls. Moreover, emotional abuse and emotional neglect have been significantlyassociated with greater SAD symptom severity [4, 5, 7, 8],even in non-clinical samples [10, 11]. One study [5] furtherfound that emotional abuse and neglect were linked togreater severity of depressive symptoms. Fewer studiesfound significant associations of physical neglect [4] andsexual abuse [7, 9] with SAD.In addition to childhood maltreatment types, whereperpetrators usually include parents and other adults,peer victimization is considered to be a further adversesocial learning experience contributing to the development of SAD. In the interactional model of SAD, Spenceand Rapee propose that exposure to peer victimizationmay increase the risk of developing SAD in individuals“who are intrinsically vulnerable “ ([1], p., 8) (e.g., due toa genetic predisposition and/or inhibited temperament),through their impact upon behavioral and cognitivefactors, including avoidance behavior or maladaptiveschemes.Therefore, a child exposed to peer victimization ismore likely to experience social interactions as harmful,which may reinforce negative beliefs about themself andrelationships with peers. This may lead to the avoidanceof social interactions, and thereby increasing levels of social anxiety [1, 12]. Indeed, studies have shown that peervictimization, including threats or acts of physical aggression (overt victimization), relational manipulation orsocial exclusion (relational victimization), and damaginga peers’ reputation (reputational victimization) is associated with social anxiety symptoms in adolescence andadulthood [13–15]. Growing evidence from prospectiveinvestigations implies that peer victimization puts children and adolescents at risk for developing social anxiety[12, 14, 16, 17], with findings differing across types ofvictimization. Especially relational victimization, which istypically initiated by friends [18] and comprises behaviorsuch as excluding someone or withholding a relationship,is most strongly associated with social anxiety comparedto overt or reputational victimization [14]. However,cross-sectional studies further suggest that socially anxious youth are also more likely to become targets for peervictimization [17, 19–21], so that peer victimization seemsto constitute both, a predictor as well as a consequence ofsocial anxiety [12, 14, 17, 22].Preliminary studies, which investigated peer victimizationand childhood maltreatment simultaneously, report inconsistent findings. While cross-sectional data [23] implies thatemotional child maltreatment and peer victimization areindependently linked to SAD symptom severity, longitudinal data [24] suggest that emotional peer victimization,Page 2 of 11but not parental emotional abuse, increases social anxietysymptoms. In this longitudinal study [24], emotional peervictimization was assessed with the items on relationalvictimization from the victimization scale of the Peer Reactions Questionnaire [25].In sum, the balance of evidence to date demonstratesthat particular forms of recalled childhood adversities,namely emotional abuse, emotional neglect, and peervictimization may have more impact on SAD than otherforms of childhood adversities. However, one of the keyquestions concerning effects of childhood adversities onSAD is the specificity of these effects. In other words,does having experienced emotional abuse, emotionalneglect, or peer victimization increase the risk for SADspecifically, any anxiety disorder, any affective disorder,or any psychopathology? The above summarized studieson child maltreatment usually recruited participants forspecific research projects, e.g. a brain imaging studies [5] orintervention trials [4, 7, 8], in which high internal validity isrequested. Comorbidity was therefore allowed only on alimited basis. In some studies, depressive disorders wereallowed [4, 8, 9], in others, these were excluded [5, 7].Assessing comorbidity, however, may be highly relevant forthe conclusions of such investigations.For example, Rapee [26] reviewed the evidence forspecificity of sexual or physical abuse as a risk factor foranxiety disorders and concluded that “sexual abuse isshown to be a risk factor for a variety of forms ofpsychopathology “(p. 73). In fact, some of the effects ofsexual abuse may rather unfold in patients with comorbidity of anxiety and affective disorders rather than in“pure” anxiety disorders only (p. 40) [27]. Beyond that,exposure to childhood adversities is associated with arange of mental health problems in later life. Forexample, child maltreatment has shown to be associatedwith mood and anxiety disorders, substance abuse,psychotic symptoms, and personality disorders [28].Similarly, peer victimization does increase the risk forseveral dimensions of psychopathology, specificallyinternalizing problems [29–31]. Only preliminary evidence suggests that social anxiety and not depressionmay be specifically linked to peer victimization [13].Taken together, key limitations in previous studies include a) the unclear specificity of the effects of childhood adversities on SAD. Most previous studiesinvestigated associations with SAD symptom severity inindividuals with SAD but did not examine whether theselinks are specific to a SAD diagnosis compared to otherdisorders. b) The neglected role of comorbid disordersin these effects, and c) limited generalizability of previous results to clinical treatment-seeking samples withhigh external validity (individuals not participating in arandomized controlled trial or recruited for a specific research project). Given the evidence that patients exposed

Brühl et al. BMC Psychiatry(2019) 19:418to childhood adversities show poorer treatment outcomes [32], research in representative treatment-seekingsamples is key in informing practitioners and developingtreatment interventions for patients commonly seen inout-patient clinics.Therefore, the primary aim of the present study is toexamine whether particular forms of recalled childhoodadversities, namely emotional abuse, emotional neglect,and peer victimization are specifically associated withSAD in adulthood or whether we find similar links inother anxiety or depressive disorders by using a clinicalsample who is seeking psychotherapy more in a routinecare setting instead of a randomized controlled trial.In order to investigate the specificity of links betweenrecalled childhood adversities and SAD, we hypothesizethat (1) recalled childhood emotional abuse, emotionalneglect, and peer victimization are more likely to be associated with SAD than with any other mental disorderwhile controlling for comorbidity, (2) childhood adversity severities will differ across SAD, specific phobia(SP), and generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) withoutcomorbidities, and (3) childhood adversity severities willdiffer between anxiety disorders and depressive disorderswithout comorbidities. The secondary aim of this studyis to clarify the role of comorbid depressive disorders inthe assumed effects of recalled childhood adversities.Therefore, (4) we expect that patients with SAD and comorbid depressive disorder will report more childhoodadversities than patients with SAD only.MethodsParticipantsData for the present cross-sectional study were obtainedfrom N 1091 treatment-seeking outpatients, who completed the CTQ before the initiation of psychotherapytreatment. All patients were assessed in a routine caresetting in one of two German outpatient clinics affiliatedwith the University of Braunschweig (n 218) or Bielefeld University (n 873). Eligible patients were 1) at least18 years old, 2) met the criteria for at least one mentalhealth diagnosis according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV TR) [33],and 3) provided their data for research purposes. Primary diagnoses of all patients (690 women, 401 men,Mage 34.83, SD 12.11) included 42% depressive disorders and 21% anxiety disorders (within 32% with SAD).Further diagnoses included reaction to severe stress, andadjustment disorders (13%), eating disorders (5%),obsessive-compulsive disorder (4%), personality disorders (4%), somatoform disorders (4%), disorders due topsychoactive substance (1%), schizophrenia, schizotypaland delusional disorders (1%), and other disorders (6%;e.g., sleep disorders, sexual dysfunction, habit and impulse disorders, dissociative conversion disorders, andPage 3 of 11hyperkinetic disorders). About half of the sample (52%)had at least one comorbid disorder. The majority of thesample (44%) had a part-time or full-time job, while 31%were students or apprentices, 3% were housewives, 7%were retired or unemployable, and 11% were unemployed (4% did not respond to this question). Mostpatients (84%) were presently married or in a relationship, 5% were single, and 11% were divorced orseparated.For the primary aim of our study, we examined differentsubgroups of patients with: (a) SAD with or without anycomorbidity (SAD / , n 171) and patients with anyother mental disorder with or without comorbidity (OD / , n 801). We further compared groups that still indicated acceptable cell numbers for analyses after excludingpatients with comorbidities: (b) patients with SAD only(SAD-, n 25), GAD only (GAD-, n 19), SP only (SP-,n 18), and (c) patients with an anxiety disorder only(AD-, n 62; i.e. SAD-, SP- or GAD-) versus patients witha depressive disorder only (DEP-, n 239; i.e. depressiveepisode, recurrent depressive disorder, or dysthymia). Forthe secondary aim of the study, we compared patientswith SAD and a comorbid depressive disorder (SAD DEP,n 143) versus SAD only (SAD-, n 25).MeasuresAssessment of diagnosisDiagnostic data were obtained using the German versionof the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCIDI) [34] to diagnose major mental disorders (DSM-IVAxis I) according to the Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders [33]. The SCID for Axis I is routinely used in both clinics. All interviewers were trainedand either licensed therapists or those in training undergoing supervision.Assessment of child maltreatmentRetrospective data on recalled child maltreatment wereassessed with the German version of the ChildhoodTrauma Questionnaire (CTQ) [6, 35]. The 28-itemversion of the CTQ contains five subscales to assessdifferent forms of trauma: emotional abuse, physicalabuse, sexual abuse, emotional neglect, and physicalneglect. Each of these subscales consists of 5 items, suchas “people in my family said hurtful or insulting thingsto me” (emotional abuse). Each item is rated from 1(never true) to 5 (very often true), so that subscale scorescan range from 5 to 25 with higher scores indicatingmore severe maltreatment. The continuous subscalescores were used to test our hypotheses. The employedversion further contained 3 items to assess minimization/denial indicating a positive response bias. Given that thesubscale physical neglect shows insufficient internalconsistence and high intercorrelations with the other

Brühl et al. BMC Psychiatry(2019) 19:418subscales [36], only the first four subscales were used totest our hypotheses. In order to describe frequency ratesof maltreatment forms, cut-offs for each subscale wereapplied according to Walker and colleagues [37]: emotional abuse 10, physical abuse 8, sexual abuse 8, andemotional neglect 15. However, frequency rates were notused to test our hypotheses due to reduced cell sizes. TheGerman version has been shown to be a reliable and validmeasure to screen for these four forms of childhoodmaltreatment. Wingenfeld and colleagues [35] found goodpsychometric properties, including high internalconsistency of all trauma scales with Cronbachs α 0.89,except for physical neglect with α 0.62. Similar, internalconsistencies in our study were high to excellent, withCronbach’s α .88 (emotional abuse), α .86 (physicalabuse), α .96 (sexual abuse), α .91 (emotional neglect),except for physical neglect (α .61).Assessment of peer victimizationThe Questionnaire of Aversive Social Experiences in thePeer Group (Fragebogen zu belastenden Sozialerfahrungen in der Peer Group, FBS) [38] was employed to retrospectively assess the exposure to various forms of peervictimization. On a list of 22 aversive social situations,such as being excluded, insulted or laughed at (e.g., “Ithappened that everyone was invited to a party, but notme”), patients reported whether they had experiencedthis situation or not (Yes or No) during childhood (age6–12) or adolescence (age 13–18). In this study, the totalsum score of all Yes responses (0–44) was used for analyses. Preliminary evaluations report satisfying psychometric properties, with solid stability over a period of 20months and good construct validity [38]. Moreover,findings suggest that the FBS may assess a distinct formof child maltreatment, due to its incremental contribution to the prediction of psychopathology beyond childmaltreatment assessed with the CTQ [31]. In our study,we obtained excellent internal consistencies for the FBSchildhood scale (Cronbach’s α .90), the adolescencescale (α .96), and the total sum score (α .97).ProcedureThe study was approved by the ethics committee of theUniversity of Braunschweig. Data for this cross-sectionalinvestigation was collected in two outpatient clinicswithin the scope of the routine diagnostic assessmentbetween 2013 and 2018. The standard routine assessment comprised structured clinical interviews and a battery of self-report questionnaires, assessing participants’demographics, mental health, and psychosocial functioning. For research purposes only, patients further completed the CTQ and the FBS in the outpatient clinic ofthe University of Braunschweig. In the outpatient clinicof Bielefeld University, the CTQ was already included inPage 4 of 11the routine diagnostic assessment and only the FBS wascompleted for research purposes only. Self-report questionnaires were completed via a paper-pencil version.Patients provided their written consent for using theanonymized data for research. A list of all available measures employed in this research project can be obtainedfrom the second and third authors.Data analysesAnalyses included the entire sample for whom CTQ and/orFBS responses were available (N 1091). Missing data analyses indicated a systematically missing of values so that wedid not impute missing values in our study (see Additional file 1A). In cases where the assumptions for parametric analyses were violated, non-parametric tests wereemployed. Demographic characteristics, rates of child maltreatment, and peer victimization are descriptively reportedwith means (M) and standard deviations (SD) for continuous variables as well as counts for categorical variables.Demographic group differences were tested with χ2 analysesand independent t-tests. Further preliminary analyses included the calculation of the CTQ minimization/denial severity across patient groups (see Additional file 1B).Intercorrelations among demographic characteristics, childmaltreatment scales, and peer victimization were calculatedusing Spearman rs (see Additional file 1C).In order to investigate, whether particular forms ofrecalled childhood adversities are more likely to be associated with SAD than with any other mental disorder, we examined the odds of developing SAD / by conducting abinary logistic regression with age, gender, occurrence ofcomorbidity, CTQ maltreatment scales, and peervictimization as independent variables (forced entrymethod). All CTQ subscales were included in the analysisof hypothesis 1 nevertheless we expected based on the literature that emotional abuse, emotional neglect, and peervictimization are more likely to be associated with SAD / . We controlled for participants age and gender by including these variables into the model because participant’sage significantly differed between our groups (see Table 1)and gender differences in social anxiety have been established [39]. Results of Nagelkerke’s R2 and HosmerLemeshow test are reported to evaluate the goodness of fitof the model. In order to find an anticipated R2 0.10, OR1.8 with a power of 95%, a sample size of n 328 was required for the logistic regression. Given that the homogeneity of covariance matrices could not be assumed,multivariate tests could not be implemented. Instead, weused multiple tests for independent samples for examiningwhether effects of childhood adversities are specific toSAD. Kruskal-Wallis tests were employed to comparechildhood adversities among the patient groups SAD-, SP-,and GAD-. Due to reduced statistical power, these resultsshould be interpreted cautiously. Independent t-tests were

Brühl et al. BMC Psychiatry(2019) 19:418Page 5 of 11Table 1 Demographic Characteristics, Child Maltreatment and Peer Victimization in the total Sample, Patients with SAD, and Patientswith other DisordersCharacteristicsTotal(n 1091)SAD / (n 192)nOD / (n 899)n(%)n(%)(%)Genderχ2Test 660.4257463.85Emotional abuse49746.808747.0341046.75.945Physical abuse27325.305126.8422224.97.590Sexual abuse17916.702714.2115217.23.311Emotional neglect42239.897741.6234539.52.596MSDMSDMSDt-Test (p)Age34.8312.1131.2910.0035.6012.39 .001Peer Victimization11.858.3813.538.7311.498.26.003Child MaltreatmentNote. M Mean, SD Standard Deviation, SAD / Social anxiety disorder with or without comorbidity, OD / Other disorders with or without comorbidity. Childmaltreatment threshold for clinical significance in CTQ established by Walker et al. [37]computed to investigate differences in childhood adversities between AD- and DEP-. In order to compare the patient groups SAD- and SAD DEP, further t-tests wereemployed. Effect sizes Hedge’s g were computed for eachcomparison by adjusting the calculation for different sample sizes. Given the multiple testing, alpha levels were Bonferroni adjusted for the number of tests (i.e. adjusted alpha:p .0028). All analyses were carried out with SPSS 24.ResultsPreliminary analysesTable 1 shows demographic characteristics, child maltreatment rates, and peer victimization for the total sample(N 1091), patients with SAD (87% with comorbidities)and patients without SAD. Descriptive analyses showedemotional abuse as the most commonly reported type ofchild maltreatment (46%), followed by emotional neglect(39%), physical abuse (25%), and sexual abuse (16%).Table 2 summarizes the extent and severity of childhood maltreatment in patients with SAD only as well aspatients with SAD and comorbidities in our study. Severities and rates found in other clinical studies,including a large sample of German in- and outpatients[35] as well as a representative sample drawn from thegeneral German Population [40], can be found in theAdditional file 1D.Emotional abuse, emotional neglect, and peervictimization are more likely to be associated with SADthan with other mental disorders (hypothesis 1)The results of the binary logistic regression are presented in Table 3. A total of n 972 cases were analyzedand the full model significantly predicted SAD / (omnibus χ2 137.94, df 8, p .001; HosmerLemeshow Test χ2 2.72, df 8, p .950). Nagelkerke’sR2 indicated that the model accounted for 22% of thevariance in SAD / . Age and the presence of comorbidity predicted SAD / . The values of the coefficients revealed that an increase of 1 year in age is associated witha decrease in the odds of SAD / by a factor of 0.97(95% CI 0.95 and 0.99). For patients without comorbidities, the chance of SAD / decreases by a factor of 0.12(95% CI 0.07 and 0.19) when compared to patients withcomorbidities. Neither emotional abuse, emotional neglect nor peer victimization was associated with SAD.Childhood adversity severities will differ across SAD, SP,and GAD only (hypothesis 2)The Kruskal-Wallis tests revealed that the patient groupsSAD-, SP-, and GAD- did not differ in their severity ofemotional abuse (χ2 [2, N 62] 0.60, p .741), physicalabuse (χ2 [2, N 62] 2.61, p .272), sexual abuse (χ2 [2,N 62] 0.91, p .634), emotional neglect (χ2 [2, N Table 2 Frequencies and Severities of Child maltreatment assessed with the CTQ in Social Anxiety DisorderEmotional AbuseNSADSAD / M (SD)Physical AbuseSexual AbuseEmotional Neglect%M (SD)%M (SD)%M (SD)%258.12 (2.88)28.005.24 (0.72)4.005.04 (0.20)0.0011.14 (3.95)28.0019210.92 (5.43)47.037.06 (3.68)26.846.49 (4.11)14.2113.60 (5.88)41.62Note. M Mean, SD Standard Deviation, % Percentage of participants meeting the threshold for clinical significance, CTQ childhood trauma questionnaire. Thresholdfor clinical significance in CTQ established by Walker et al. [37]. SAD- Social anxiety disorder only, SAD / Social anxiety disorder with or without comorbidity

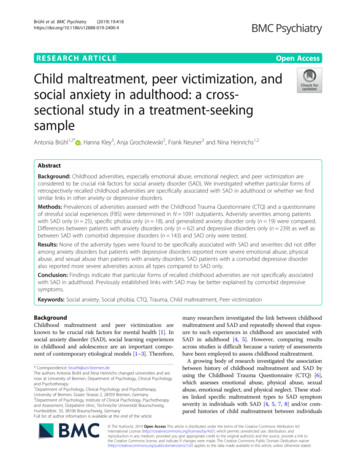

Brühl et al. BMC Psychiatry(2019) 19:418Page 6 of 11Table 3 Results of the Logistic Regression for SAD DiagnosisIndependent variablep valueOdds-Ratio95% CIAge .001.97[0.95, 0.99]Gender.0621.44[0.98, 2.11]Comorbidity .001.12[0.07, 0.19]Emotional abuse.7671.01[0.96, 1.06]Physical abuse.127.95[0.88, 1.02]Sexual abuse.289.97[0.93, 1.02]Emotional neglect.5861.01[0.97, 1.05]Peer victimization.3481.01[0.99, 1.04]Note. N 972 patients (n 171 SAD / , n 801 OD / ) were included in theanalysis. Criterion: diagnosis (0 other disorders OD / , 1 SAD / ).Independent variables: Age in years, gender (0 male; 1 female),comorbidity (0 comorbidity, 1 no comorbidity), emotional abuse (CTQscale), physical abuse (CTQ scale), sexual abuse (CTQ scale), emotional neglect(CTQ scale), peer victimization (FBS total score). CI confidence interval62] 0.15, p .930), or peer victimization (χ2 [2, N 60] 2.29, p .318) with the adjusted alpha p .0028.Figure 1 illustrates these findings.Childhood adversity severities will differ between anxietyand depressive disorders (hypothesis 3)Multiple independent t-tests showed that the DEPgroup reported significantly more severe emotionalabuse (t 3.64, df 137.63, p .001, g .42), physicalabuse (t 2.91, df 149.79, p .004, g .32), and sexual abuse (t 4.51, df 286.27, p .001, g .35) compared to patients with AD- (adjusted alpha: p .0028).No significant differences emerged for emotional neglect(t 2.07, df 297, p .039, g .30) and peervictimization (t 2.83, df 285, p .005, g .41, seeFig. 2).Patients with SAD and comorbid depressive disorder willreport more childhood adversity severities than patientswith SAD only (hypothesis 4)Results of further independent t-tests showed that patients with SAD DEP reported significantly more severeemotional abuse (t 4.65, df 65.09, p .001, g 0.65),physical abuse (t 6.00, df 165.83, p .001, g 0.59),sexual abuse (t 4.81, df 144.93, p .001, g 0.44),emotional neglect (t 3.23, df 46.38, p .002, g 0.53), and peer victimizations (t 6.68, df 47.55,p .001, g 1.01) than patients with SAD- (Fig. 3).DiscussionThe primary aim of the study was to investigate whethereffects of different forms of recalled child maltreatmentand peer victimization on SAD are specific to SAD orwhether we find similar effects in other disorders as well.Four key findings emerged. Contrary to our expectations,none of the different child maltreatment types or peervictimization were found to be predictive for a SAD diagnosis in adulthood in an exclusively clinical sample. Thus,none of these childhood adversities seem to be more likelyassociated with SAD than with other disorders in thepresent sample. These findings seem inconsistent withprevious findings, which may be partially explained by differences in the study design. Previous studies usually investigated the associations between childhood adversitiesand symptom severity in SAD samples [4, 8] and/or compared SAD patients with healthy controls [5], whereas weinvestigated links between childhood adversities and acategorical diagnosis, assessed with a clinical interview.Secondly, neither any form of child maltreatment norpeer victimizations significantly differed among patientswith SAD, SP, or GAD without comorbidities. Althoughprevious studies repeatedly showed that at least childhoodemotional abuse and emotional neglect seems to bestrongly linked to SAD severity in adulthood [4, 5, 7–9],these effects may not be specific to SAD, but rather applyfor other anxiety disorders as well. Indeed, preliminary research indicates that child maltreatment as well as peervictimization are associated with an increased risk for anyanxiety disorder, including SP and GAD [15, 30, 41–43].However, studies investigating links between other anxietydisorders than SAD or PTSD and child maltreatmentassessed with the CTQ are scarce, limiting the comparability with our results.The third key finding implies that effects may not onlybe non-specific to SAD, but broader non-specific toFig. 1 Group differences in means of childhood adversity severity across SAD-, SP-, and GAD-. Emotional abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, andemotional neglect assessed with the CTQ; Peer victimization assessed with the FBS; Cut-off according to Walker et al. [37]. Means and standarddeviations can be found in the Additional file 1E1

Brühl et al. BMC Psychiatry(2019) 19:418Page 7 of 11Fig. 2 Group differences in means of childhood adversity severity between anxiety disorders and depressive disorders without comorbidity.Emotion

using the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ) [ 6], which assesses emotional abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional neglect, and physical neglect. These stud-ies linked specific maltreatment types to SAD symptom severity in individuals with SAD [4, 5, 7, 8]and/orcom-