Transcription

CognitiveB e h a v i o u ra lT h e ra p yC O R E I N F O R M AT I O NDOCUMENTMARCH 20075CARMHACentre for Applied Research inMental Health and AddictionFaculty of Health SciencesSimon Fraser University

Centre for AppliedResearch in Mental Healthand Addictions (CARMHA)www.carmha.caSFU @ Harbour Centre, Faculty of Health Sciences7200 - 515 W. Hastings Street, Vancouver BC V6B 5K3Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication DataSomers, Julian.Cognitive behavioural therapy [electronic resource]“The Core information document on cognitive-behavioural therapy was developed by the Centrefor Applied Research in Mental Health and Addiction (CARMHA) at Simon Fraser Universityunder the direction of the Mental Health and Addiction Branch, Ministry of Health”—P. i.“Principal author: Julian Somers ; contributing author: Matthew Querée”Available also on the Internet.ISBN 0-7726-5598-71. Cognitive therapy. 2. Mental illness – Treatment. 3. Mental illness - Bibliography. I. Querée, Matthew.II. British Columbia. Mental Health and Addictions.III. Simon Fraser University. Centre for Applied Researchin Mental Health and Addictions. IV. British Columbia. Ministry of Health.RC489.C63S65 2006616.89’14209711C2006-960147-X

DisclaimerResearch in the medical and behavioural sciences and informationabout cognitive behavioural therapy and pharmacological treatmentsfor mental disorders and addictions is rapidly changing. Furthermore,medical and health concerns are unique to each individual and requireindividual attention and care. Accordingly, it is recommended thatyou consult with your physician and a qualified cognitive behaviouralpractitioner before acting on any of the information in this book.Core Information Document on Cognitive-Behavioural TherapyThe Core Information Document on Cognitive-Behavioural Therapywas developed by the Centre for Applied Research in Mental Healthand Addictions (CARMHA) at the Simon Fraser University under thedirection of the Mental Health and Addictions Branch, Ministry ofHealth, Government of British Columbia. This document is part of anumber of best practice documents released by government to supporthigh quality mental health and addictions care in the province.N OT E : The terms cognitive behavioural therapy, cognitive-behaviourtherapy, and cognitive-behavioural therapy are synonymous and usedinterchangeably throughout this document.C O G N I T I V E B E H AV I O U R A L T H E R A P YiCORE INFORMATION DOCUMENT

Principal AuthorJulian Somers, MSc., PhDContributing AuthorMatthew Querée, BA (Hons.), M.App.Psych.Research AssistantsJessica BroderickBonnie LeungBritish Columbia Ministry of Health AdvisorsGulrose Jiwani, RN MNAddictions Performance Specialist, Mental Health and AddictionsWayne Fullerton, Ed.D, R.Psych.Mental Health SpecialistThe authors wish to thank the following individuals and groups for valuableadvice and assistance during the development of the current report:Lead Research ConsultantsWarren Mansell, BAHons (Cantab) DPHil (Oxford) DCLinPsy CPsycholLecturer, Department of PsychologyUniversity of Manchester, UKRoz Shafran, PhDPsychologist, Department of PsychiatryOxford University, UKC O G N I T I V E B E H AV I O U R A L T H E R A P YiiCORE INFORMATION DOCUMENT

CBT Expert and Stakeholder ReviewersDan Bilsker, PhD, RPsychClinical Assistant Professor,Department of PsychiatryUniversity of British ColumbiaKaren R. Cohen, PhDAssociate Executive Directorand Registrar AccreditationCanadian Psychological AssociationPeter Coleridge, Senior AdvisorProvincial Health Services AuthorityKenneth D. Craig, PhD, RPsychProfessor Emeritus,Department of PsychologyUniversity of British ColumbiaPeter Mclean, PhD, RPsychDirector, Anxiety Disorders UnitProfessor, Department of PsychiatryUniversity of British ColumbiaJohn Service, PhD, CPsychExecutive DirectorCanadian Psychological AssociationRajpal Singh, PhD, RPsychPsychologist,Vancouver-Richmond Health BoardMulticultural Mental HealthLiaison Worker, South AsianMental Health TeamPatrick Smith, PhDSenior Advisor, Mental Healthand AddictionsProvincial Health Services AuthorityPhil UpshallMood Disorders Society of CanadaDavid Wong, PhD, RPsychPsychologist, Chinese Mental WellnessAssociation of CanadaBill MussellChairman and PresidentNative Mental HealthAssociation of CanadaPrincipal Educator, Sal’i’shan InstituteMichelle Patterson, PhDResearch Scientist,CARMHA, SFUSimon A. Rego, PsyDAssistant Professor,Psychiatry and Behavioral SciencesAssociate Director of Training,Adult CBTAlbert Einstein College of MedicineMontefiore Medical CenterNew York, USAC O G N I T I V E B E H AV I O U R A L T H E R A P YiiiCORE INFORMATION DOCUMENT

C O G N I T I V E B E H AV I O U R A L T H E R A P YivCORE INFORMATION DOCUMENT

Ta b l e o f C o n t e n t sC H A P T E R 1 : I N T R O D U C T I O N TO T H E C O R E I N F O R M AT I O N D O C U M E N TT h e N e e d f o r a “ C o re I n f o r m a t i o n D o c u m e n t ”A R e s o u rc e f o r Va r i o u s R e a d e rsWh a t i s C B T ?Fo r m s o f C B TW h o P ro v i d e s C B T ?C l i n i c a l Tr a i n i n g i n C B T1123445C H A P T E R 2 : W H AT I S C O G N I T I V E - B E H AV I O U R A L T H E R A P Y ( C B T ) ?1.0 T h i n k i n g2.0 Behaviour3 . 0 T h e T h e ra p y78910CHAPTER 3: D E P R E S S I O N1 . 0 T h e C o n t e n t o f t h e T h e ra p y2 . 0 E f f e c t s o n S y m p t o m s i n D i f f e re n t Pa t i e n t Po p u l a t i o n s3.0 Effects on Relapse Rates4 . 0 E f f e c t s o n G l o b a l M e a s u re s o f F u n c t i o n i n g5 . 0 C o m b i n e d C B T a n d P h a r m a c o l o g i c a l Tr e a t m e n t6.0 Comparison with Non-Specific Interventionsa n d O t h e r P s y c h o l o g i c a l T h e ra p i e s7 . 0 B r i e f T h e ra p y a n d ‘ R a p i d R e s p o n d e rs ’8.0 Self-Help and CBT9 . 0 W h a t P re d i c t s a B e t t e r R e s p o n s e t o C B T f o r D e p re s s i o n ?1 0 . 0 R o l e o f t h e Fa m i l y11.0 Summary151618181919CHAPTER 4: BIPOLAR DISORDER1 . 0 T h e C o n t e n t o f t h e T h e ra p y2.0 Effects of CBT3.0 Comparison with Non-Specific Interventionsa n d O t h e r P s y c h o l o g i c a l T h e ra p i e s4 . 0 W h a t P re d i c t s a B e t t e r R e s p o n s e t o C B T f o r B i p o l a r D i s o rd e r ?5 . 0 R o l e o f t h e Fa m i l y6.0 SummaryC O G N I T I V E B E H AV I O U R A L T H E R A P YvCORE INFORMATION DOCUMENT19202021222225262828292930

Ta b l e o f C o n t e n t sC H A P T E R 5 : S U B S TA N C E U S E D I S O R D E R S1 . 0 T h e C o n t e n t o f t h e T h e ra p y2 . 0 E f f e c t s o n S y m p t o m s i n D i f f e re n t Po p u l a t i o n s3.0 Effects on Relapse Rates4 . 0 C o m b i n e d C B T a n d P h a r m a c o l o g i c a l Tr e a t m e n t5.0 Comparison with Non-Specific Interventionsa n d O t h e r P s y c h o l o g i c a l T h e ra p i e s6 . 0 B r i e f I n t e r v e n t i o n s, B r i e f T h e ra p y a n d C B T7.0 Self-Help and CBT8 . 0 C o n c u r re n t D i s o rd e rs a n d C B T9.0 Wh a t P re d i c t s A B e t t e r R e s p o n s e To C B T w i t h S u b s t a n c e U s e D i s o rd e rs ?1 0 . 0 R o l e o f t h e Fa m i l y11.0 SummaryCHAPTER 6: G E N E R A L I Z E D A N X I E T Y D I S O R D E R ( G A D )1 . 0 T h e C o n t e n t o f t h e T h e ra p y2 . 0 E f f e c t s o n S y m p t o m s i n D i f f e re n t Po p u l a t i o n s3 . 0 G ro u p Tr e a t m e n t s4.0 Comparison with Non-Specific Interventionsa n d O t h e r P s y c h o l o g i c a l T h e ra p i e s5.0 Comparison with Pharmacological Interventions6.0 Self-Help and CBT7 . 0 W h a t P re d i c t s a B e t t e r R e s p o n s e t o C B T ?8 . 0 R o l e o f t h e Fa m i l y9.0 SummaryC H A P T E R 7 : PA N I C D I S O R D E R1 . 0 T h e C o n t e n t o f t h e T h e ra p y2 . 0 E f f e c t s o n S y m p t o m s i n D i f f e re n t Po p u l a t i o n s3 . 0 G ro u p Tr e a t m e n t s4.0 Comparison with Non-Specific Interventionsa n d O t h e r P s y c h o l o g i c a l T h e ra p i e s5.0 Comparison with Pharmacological Interventions6 . 0 P re d i c t o rs o f O u t c o m e7 . 0 P re s e n t a t i o n a t E m e rg e n c y D e p a r t m e n t s8.0 Self-Help and CBT9 . 0 R o l e o f t h e Fa m i l y10.0 SummaryC O G N I T I V E B E H AV I O U R A L T H E R A P YviCORE INFORMATION 505354575757585858595959

Ta b l e o f C o n t e n t sCHAPTER 8: OBSESSIVE-COMPULSIVE DISORDER (OCD)1 . 0 T h e C o n t e n t o f t h e T h e ra p y2 . 0 E f f e c t s o n S y m p t o m s i n D i f f e re n t Po p u l a t i o n s3 . 0 L o n g - Te r m O u t c o m e4.0 Pharmacological Options5 . 0 C o m b i n e d C B T a n d P h a r m a c o l o g i c a l Tr e a t m e n t6.0 Comparison with Non-Specific Interventionsa n d O t h e r P s y c h o l o g i c a l T h e ra p i e s7 . 0 B r i e f T h e ra p y a n d ‘ R a p i d R e s p o n d e rs ’8.0 Tr e a t m e n t R e f ra c t o r y O C D9.0 Self-Help and CBT1 0 . 0 W h a t P re d i c t s a B e t t e r R e s p o n s e t o C B T ?1 1 . 0 R o l e o f t h e Fa m i l y12.0 Summary616365656666CHAPTER 9: SPECIFIC PHOBIAS1 . 0 T h e C o n t e n t o f t h e T h e ra p y2 . 0 E f f e c t s o n S y m p t o m s i n D i f f e re n t Po p u l a t i o n s3 . 0 G ro u p Tr e a t m e n t s4.0 Comparison with Non-Specific Interventionsa n d O t h e r P s y c h o l o g i c a l T h e ra p i e s5.0 Comparison with Pharmacological Interventions6.0 Self-Help and CBT7 . 0 W h a t P re d i c t s B e t t e r R e s p o n s e s t o C B T ?8 . 0 R o l e o f t h e Fa m i l y9.0 Summary71717374747474757575CHAPTER 10: SCHIZOPHRENIA A N D P S Y C H O S I S1 . 0 T h e C o n t e n t o f t h e T h e ra p y2.0 Tr e a t m e n t Po p u l a t i o n s3.0 Effects on Symptoms4.0 Effects on Relapse Rates5 . 0 E f f e c t s o n G l o b a l M e a s u re s o f F u n c t i o n i n g6.0 Effects on Social A n x i e t y7.0 Early Intervention8.0 Is CBT Superior to a Non-Specific Psychosocial Intervention?9 . 0 W h a t P re d i c t s a B e t t e r R e s p o n s e t o C B T ?1 0 . 0 R o l e o f t h e Fa m i l y1 1 . 0 G e n e ra l i z a t i o n t o C l i n i c a l S e t t i n g s a n d S t e p p e d C a re12.0 Summary77787980808081818182828283C O G N I T I V E B E H AV I O U R A L T H E R A P YviiCORE INFORMATION DOCUMENT67676768686969

Ta b l e o f C o n t e n t sC H A P T E R 1 1 : E AT I N G D I S O R D E R S1 . 0 T h e C o n t e n t o f t h e T h e ra p y2 . 0 E f f e c t s o n S y m p t o m s i n D i f f e re n t Pa t i e n t Po p u l a t i o n s3.0 Effects on Relapse Rates4 . 0 C o m b i n e d C B T a n d P h a r m a c o l o g i c a l Tr e a t m e n t5.0 Comparison with Non-Specific Interventionsa n d O t h e r P s y c h o l o g i c a l T h e ra p i e s6 . 0 G ro u p C B T7 . 0 W h a t P re d i c t s a B e t t e r R e s p o n s e t o C B T w i t h E a t i n g D i s o rd e rs ?8.0 Tr e a t m e n t R e f ra c t o r y E a t i n g D i s o rd e rs9.0 Self-Help and CBT1 0 . 0 R o l e o f t h e Fa m i l y11.0 Summary90919191929393C H A P T E R 1 2 : S T E P P E D A P P R OACH TO C A R E A N D A LT E R N AT I V EWAYS O F D E L I V E R I N G C B T95RESOURCE LIST1.0 We b s i t e s2.0 Vi d e o s, D V D s, a n d A u d i o t a p e s3.0 Tr a i n i n g C o u rs e s a n d Wo r k s h o p s4 . 0 E v a l u a t e d C o m p u t e r S o f t w a re t o a s s i s t i n C B T Tr e a t m e n t5 . 0 B o o k s a n d Tr e a t m e n t M a n u a l s9999102103104105REFERENCESC h a p t e r 1 I n t ro d u c t i o nC h a p t e r 2 W h a t i s C o g n i t i v e B e h a v i o u ra l T h e ra p y ( C B T ) ?C h a p t e r 3 D e p re s s i o nC h a p t e r 4 B i p o l a r D i s o rd e rC h a p t e r 5 S u b s t a n c e U s e D i s o rd e rsC h a p t e r 6 G e n e ra l i z e d A n x i e t y D i s o rd e r ( G A D )C h a p t e r 7 Pa n i c D i s o rd e rC h a p t e r 8 O b s e s s i v e - C o m p u l s i v e D i s o rd e r ( O C D )Chapter 9 S p e c i f i c P h o b i a sC h a p t e r 1 0 S c h i z o p h re n i a a n d P s y c h o s i sC h a p t e r 1 1 E a t i n g D i s o rd e rsC h a p t e r 1 2 S t e p p e d A p p ro a c h t o C a re A n d A l t e r n a t i v e w a y sof Delivering CBT109109109109113114120122125127128130C O G N I T I V E B E H AV I O U R A L T H E R A P YviiiCORE INFORMATION DOCUMENT8586888990133

C H A P T E R 1 I n t ro d u c t i o n t o t h e C o re I n f o r m a t i o n D o c u m e n tT h e N e e d f o r a “ C o re I n f o r m a t i o n D o c u m e n t ”Cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) holds a unique status in the fieldof mental health – CBT is effective for many psychological problems, isrelatively brief, and is well received by individuals. A large volume ofresearch has been published regarding CBT, including a number ofwell-designed studies involving people in “real world” clinical settings.Yet despite this large base of evidence, information about CBT has notbeen well communicated to consumers, families, and providers of healthcare. Consequently, CBT is not being used as extensively as the researchwould warrant.Many individuals (consumers, families, and professionals alike) areunaware of the effectiveness of CBT for different problems. There isadditional uncertainty about the effectiveness of different formats ofCBT (for example, individual, group or self-help formats), who canprovide CBT, how to access their services, and other treatments withwhich CBT is used (for example, the use of medication and CBT together).This Core Information Document has been assembled for the benefit ofindividuals, families and service providers interested in a broad summaryof information relating to CBT and its effectiveness.CBT is attracting increasing levels of interest from health care professionals,consumers and families. A variety of factors may contribute to this risein popularity. First, recent decades have seen a growing recognitionof the high prevalence rates of many psychological problems. Mentaldisorders negatively affect the quality of life for the person as well as hisor her family. Many of these disorders (including depression, anxiety,and alcohol problems) have been shown to respond well to CBT. Second,we face increased demands for efficient and cost-effective health careservices. CBT has the benefits of being structured, effective and, inmost cases, relatively brief. Third, people are increasingly interested inalternatives to medications. In some cases, CBT represents a proven, andsometimes superior, alternative to medication. In other cases, CBT is abeneficial addition to medication, hastening improvement and helpingto maintain improvements over time. Fourth, CBT models “consumerfocused care”, in which practitioners and individuals work together tobuild the tools individuals need to make changes necessary to livingC O G N I T I V E B E H AV I O U R A L T H E R A P Y1CORE INFORMATION DOCUMENT

C H A P T E R 1 I n t ro d u c t i o n t o t h e C o re I n f o r m a t i o n D o c u m e n tbetter. Fifth, the strategies and skills of CBT can be applied to many oflife’s challenges. The strategies and skills a person acquires to managedepression, for example, can also be used to manage chronic pain,control drinking or maintain exercise. The effectiveness of CBT inchanging and maintaining changes in behaviour makes it veryimportant to consumers and to health care services.A R e s o u rc e f o r Va r i o u s R e a d e rsInterest in CBT has been expressed among diverse groups inBritish Columbia, including policy makers, health administrators,health service providers who are non-specialists in mental health,as well as consumers and their families. This Core InformationDocument is offered as a resource to each of these groups. Thereis a vast literature relating to CBT, including books, articles andinternet resources. This document provides a brief overview of CBTand summarizes evidence supporting the effectiveness of CBT fora variety of psychological problems.Many resources relating to CBT appear throughout the text, includingweb and print based resources for consumers, educational resourcesfor health care professionals, and sources of further information forinterested readers. Most of the information has been organizedaround the diagnostic labels used in the International Classificationof Diseases1 and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual2 (Fourth Edition Text Revision). The layout of the Core Information Document is intendedto serve as a convenient reference to clinicians, consumers and familymembers who are interested in the application of CBT for a particulartype of problem. Vignettes (hypothetical) are provided to brieflyillustrate the types of psychological problems considered in eachchapter. Diagnostic criteria are provided as well, representing theformal definitions used in research on CBT.C O G N I T I V E B E H AV I O U R A L T H E R A P Y2CORE INFORMATION DOCUMENT

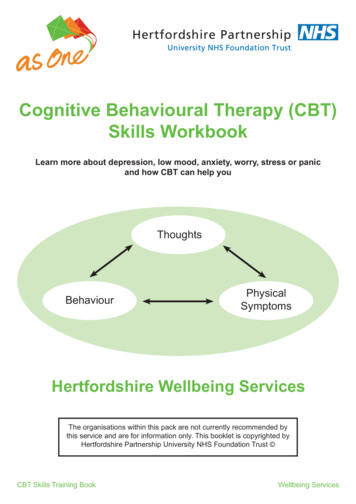

C H A P T E R 1 I n t ro d u c t i o n t o t h e C o re I n f o r m a t i o n D o c u m e n tWhat is CBT?CBT is a psychological treatment that addresses the interactions betweenhow we think, feel and behave. It is usually time-limited (approximately10-20 sessions), focuses on current problems and follows a structuredstyle of intervention. The development and administration of CBT havebeen closely guided by research. Evidence now supports the effectivenessof CBT for many common mental disorders. For some disorders, carefullydesigned research has led international expert consensus panels toidentify CBT as the current “treatment of choice”.CBT is less like a single intervention and more like a family oftreatments and practices. Practitioners of CBT may emphasize differentaspects of treatment (cognitive, emotional, or behavioural) based onthe training of the practitioner. Nevertheless, the identified techniquesof CBT prove their family resemblance in a number of ways. Alltechniques and approaches to CBT are practically applied. What getsused (that is, which technique for which problem) is what has beenproven effective and the techniques themselves derive from science(for example, the ‘behavioural experiments’ used to help peopleovercome feared objects or situations). CBT has been studied andeffectively implemented with persons who have multiple andcomplex needs, and who may be receiving additional forms oftreatment, or have had no success with other kinds of treatment.C O G N I T I V E B E H AV I O U R A L T H E R A P Y3CORE INFORMATION DOCUMENT

C H A P T E R 1 I n t ro d u c t i o n t o t h e C o re I n f o r m a t i o n D o c u m e n tFo r m s o f C B TCBT continues to evolve with different formats and emphases asresearch support emerges. The majority of evidence supporting CBTis drawn from studies involving expert practitioners working withindividuals over a specified number of sessions (for example, between10 and 20 one-hour sessions). A smaller number of studies supports theeffectiveness of CBT when administered in groups. The principlesof CBT have also been incorporated in some self-directed resources(for example, self-help books, computer programs). Together, theseinterventions represent an emerging continuum or range of stepsto the delivery of CBT. Individuals who do not respond to an initialstep, for example “bibliotherapy”, could be redirected to a facilitatedself-care program, group CBT, or one-on-one CBT as needed. Treatmentplanning and selection of procedures are based on discussion andjudgment of health service providers trained in CBT and involved inthe care.W h o P ro v i d e s C B T ?The appropriate and effective use of CBT presumes the practitioneris a qualified health practitioner with training in assessment andtreatment of mental health problems and specific training in CBT.The general clinical skills required of the practitioner include theabilities to establish a collaborative therapeutic alliance, to assessand address complications of mental disorders (for example, risk ofsuicide in depression) and to conduct a differential diagnosis of mentaldisorders. All CBT work, no matter the specific treatment or technique,begins with a careful assessment of the person’s clinical disorder(s).Diagnosis is necessary in order to determine which, if any, of the CBTtechniques are best suited for a particular individual.C O G N I T I V E B E H AV I O U R A L T H E R A P Y4CORE INFORMATION DOCUMENT

C H A P T E R 1 I n t ro d u c t i o n t o t h e C o re I n f o r m a t i o n D o c u m e n tC l i n i c a l Tr a i n i n g i n C B TClinical training in CBT involves both instruction and supervised clinicalexperience. Training in CBT is typically available in doctoral programsof clinical psychology. The Canadian Psychological Association and theAmerican Psychological Association each accredit university-based doctoralprograms as well as internships operated most often by hospitals,psychological service centres or community health centres. Bothaccrediting bodies mandate the use of evidence-based treatments,most commonly CBT. Provincial and territorial regulatory bodies licensepsychologists, like other health care practitioners in Canada. Regulatorybodies hold their member psychologists accountable to meeting andmaintaining standards of practice.Beck and colleagues (1979) were among the first to emphasize theneed for intensive training in CBT.3 Training in CBT is available topracticing or regulated health care professionals who wish to extendtheir scope of practice. This training is provided through fellowshipsat universities and through private training centres. Admission to thistype of training is typically restricted to professionals who alreadypossess the general clinical skills referred to earlier in this chapter.Training is then provided through a balance of on-site classroom oronline instruction interspersed with clinical supervision (typically notless than one hour per week). While there is no consensus about howmuch or how long a practitioner must train to deliver CBT competently,the process of developing competency in CBT often lasts 12 months forestablished mental health service providers (regardless of whether thetraining is provided through a public or private institution). Oncetraining is completed, the practitioner must also remain up-to-datewith new developments in the research and practice of CBT.Demand for CBT exceeds the supply of health care professionals who aretrained and qualified to provide it. Current research is looking at waysto make treatment more accessible to those who need it. Health carepractitioners and their professional associations are also working withgovernments to improve the accessibility of these evidence-based servicesto Canadians. As these developments proceed, documents like this onecan help improve understanding and awareness of CBT, and serve as alink to effective resources and care.C O G N I T I V E B E H AV I O U R A L T H E R A P Y5CORE INFORMATION DOCUMENT

C O G N I T I V E B E H AV I O U R A L T H E R A P Y6CORE INFORMATION DOCUMENT

C H A P T E R 2 W h a t i s C o g n i t i v e - B e h a v i o u ra l T h e ra p y ( C B T ) ?CBT is a process of teaching, coaching, and reinforcingpositive behaviours. CBT helps people to identifycognitive patterns or thoughts and emotions thatare linked with behaviours.James had always thought of himself as a worrierbut he had never experienced psychiatric illness.However, at the age of 43, James lost his job as a car mechanicand developed depression over the following months. Hebegan to feel very little pleasure out of his daily activities,many of which he had given up. He felt tired most of the day, haddifficulty concentrating and slept for over 12 hours a night. As hissymptoms became worse, he became increasingly worried that hemay have an incurable brain disease. He visited his general practitionerwho was unable to find any evidence of a physical problem.Instead, she recognized the symptoms of depression immediately.James tentatively accepted the diagnosis and asked how he couldbe helped. The doctor explained how a course of CBT with atrained CBT practitioner might be a good option. She explainedto him that there was good evidence that CBT could help peoplewith his level of symptoms, but if he was unsatisfied after thecourse of CBT, he could then try a course of antidepressants. Heagreed and the CBT practitioner was able to meet him for anassessment three weeks later.C O G N I T I V E B E H AV I O U R A L T H E R A P Y7CORE INFORMATION DOCUMENT

C H A P T E R 2 W h a t i s C o g n i t i v e - B e h a v i o u ra l T h e ra p y ( C B T ) ?1.0 T h i n k i n gDifferent people can think differently about the same event. The wayin which we think about an event influences how we feel and how weact. A classic example is that when looking at a glass of water filledhalfway, one person will see it half empty and feel discouraged andthe other sees it half full and feels optimistic. People do not have tocontinue to think about their experiences in the same way for theirentire lives. By identifying dysfunctional thoughts and by learning tothink differently about their experiences, people can feel differentlyabout these experiences, and in turn, behave differently.Most of the time people believe things about themselves and thepeople around them because they have good evidence for their beliefs.However, people are often very selective in the evidence that theyfocus on (or what they believe to be “fact”). A depressed individualmay remember the person who ignored her in a conversation but notremember the person who found her interesting. Therefore, she mayconclude, “I am a boring person”. Cognitive-behavioural practitionershelp people understand how, by selecting particular evidence to focuson, they can end up forming beliefs that are ‘cognitive distortions’.The individual may not even be aware that they have formed thesebeliefs. Such cognitive distortions are problematic, not only becausethey can be inaccurate, but also because they contribute (more thannecessary) to debilitating negative emotions or avoidance of troublingsituations. People can learn to recognize their automatic thoughts,monitor and scrutinize these thoughts, and pay attention to evidencethat supports alternative beliefs (for example, “Some people find mepleasant and interesting to talk to”).C O G N I T I V E B E H AV I O U R A L T H E R A P Y8CORE INFORMATION DOCUMENT

C H A P T E R 2 W h a t i s C o g n i t i v e - B e h a v i o u ra l T h e ra p y ( C B T ) ?2.0 BehaviourWhat we do affects how we feel and think. The individual, who dealswith an upcoming exam by putting off his studies until the last minute,is likely to experience more distress on the day of the exam than anindividual who has studied well in advance. CBT helps people to learnnew behaviours and new ways of coping with events, often involvingthe learning of particular skills.An example is the development of social skills. Poor social skills canlead to a lack of support and less ability to deal with problematicsituations, such as criticism or intimacy. Success in social situations mayalso be key in developing self-esteem and focusing on performingactivities as laid out in CBT sessions.Emphasizing behavioural change may also be important to fearreduction. Avoidance is a central feature of anxiety disorders.Unfortunately, avoidance can further the fear of anxious situations,and can place severe limits on an individual’s ability to freely engage ina full range of daily activities. Exposing individuals to fearful situationsgradually and safely (for example, in the practitioner’s office) is aprimary means of weakening the link between a feared situationand the anxious symptoms it triggers.C O G N I T I V E B E H AV I O U R A L T H E R A P Y9CORE INFORMATION DOCUMENT

C H A P T E R 2 W h a t i s C o g n i t i v e - B e h a v i o u ra l T h e ra p y ( C B T ) ?3 . 0 T h e T h e ra p yBesides its special focus on the relationships between how we think,feel and behave, the following are fundamental to the practice of CBT.3.1 Qualities of the Therapeutic RelationshipThe relationship between a qualified CBT practitioner and individualseeking treatment is collaborative. They work together to try tounderstand the person’s difficulties and what may be contributingto them. The practitioner is an expert on CBT whereas the individualis an expert on her own life and experiences. During therapy, bothof them work together to generate and try out new ways for theperson to think and behave. In CBT, the therapeutic relationship issometimes seen as one of “coaching”; the practitioner uses his/herexpertise to challenge the person’s thinking and guide them toexplore various alternatives.3.2 Goal-settingAfter identifying the individual’s problems, it is important forthe qualified CBT practitioner and individual to set goals togetherto deal with these problems. For example, a depressed personwho experiences anxiety in public places may identify small goals(such as, leaving the house 1-2 more times per week) in order togradually reduce her anxiety and feel more comfortable in public.3.3 Focus on the PresentThe past cannot be changed, but the way we think about the pastcan be (as can the present and the future!). It is often distress in thepresent and hope for the future that lead an individual into treatment.CBT is focused mainly on what the individual feels and how she iscoping in the present. However, feelings and behaviour are oftendetermined by past experiences. For example, the present focus forthe individual described in the goal-setting section would be thebeliefs and fears she has about going out in public. In addressing andchanging her beliefs about being out in public, she may recall a pastpublic situation(s) which was frightening (for example, “I saw someonehave their purse snatched on the subway”) or an experience that wasrelated in some way to the development of her fear (for example, “Myparents continually talked about how the streets were unsafe an

Cognitive behavioural therapy [electronic resource] “The Core information document on cognitive-behavioural therapy was developed by the Centre for Applied Research in Mental Health and Addiction (CARMHA) at Simon Fraser University under the direction of the Ment