Transcription

THE BIBLEPERSONAL SIZENew LivingTranslation SECOND EDITIONTyndale House Publishers, Inc.CAROL STREAM, ILLINOIS

Visit Tyndale’s exciting Web site at www.tyndale.com.The Life Recovery Bible, copyright 1998 by Tyndale House Publishers, Inc., Carol Stream, Illinois 60188. All rights reserved.Notes and Bible helps copyright 1998 by Stephen Arterburn and David Stoop. All rights reserved.Published in association with the literary agency of Alive Communications, Inc., 1465 Kelly Johnson Blvd., ColoradoSprings, CO 80920.The Life Recovery Bible is an edition of the Holy Bible, New Living Translation.Holy Bible, New Living Translation, copyright 1996, 2004 by Tyndale Charitable Trust. All rights reserved.The text of the Holy Bible, New Living Translation, may be quoted in any form (written, visual, electronic, or audio) up toand inclusive of five hundred (500) verses without express written permission of the publisher, provided that the versesquoted do not account for more than 25 percent of the work in which they are quoted, and provided that a complete bookof the Bible is not quoted.When the Holy Bible, New Living Translation, is quoted, one of the following credit lines must appear on the copyright pageor title page of the work:Scripture quotations marked NLT are taken from the Holy Bible, New Living Translation, copyright 1996, 2004.Used by permission of Tyndale House Publishers, Inc., Carol Stream, Illinois 60188. All rights reserved.Scripture quotations are taken from the Holy Bible, New Living Translation, copyright 1996, 2004. Used bypermission of Tyndale House Publishers, Inc., Carol Stream, Illinois 60188. All rights reserved.Unless otherwise indicated, all Scripture quotations are taken from the Holy Bible, New Living Translation, copyright 1996, 2004. Used by permission of Tyndale House Publishers, Inc., Carol Stream, Illinois 60188. All rightsreserved.When quotations from the NLT text are used in nonsalable media, such as church bulletins, orders of service, newsletters,transparencies, or similar media, a complete copyright notice is not required, but the initials NLT must appear at the end ofeach quotation.Quotations in excess of five hundred (500) verses or 25 percent of the work, or other permission requests, must beapproved in writing by Tyndale House Publishers, Inc. Send requests by e-mail to: permission@tyndale.com or call630-668-8300, ext. 8817.Publication of any commentary or other Bible reference work produced for commercial sale that uses the New LivingTranslation requires written permission for use of the NLT text.TYNDALE, New Living Translation, NLT, the New Living Translation logo, Tyndale’s quill logo, and Life Recovery are registeredtrademarks of Tyndale House Publishers, Inc.ISBN-13: 978-1-4143-1625-3 ISBN-10: 1-4143-1625-9 HardcoverISBN-13: 978-1-4143-1626-0 ISBN-10: 1-4143-1626-7 SoftcoverPrinted in the United States of America12 11 10 09 08 0710 987654321Tyndale House Publishers and Wycliffe Bible Translators share the vision for an understandable, accurate translation of theBible for every person in the world. Each sale of the Holy Bible, New Living Translation, benefits Wycliffe Bible Translators.Wycliffe is working with partners around the world to accomplish Vision 2025—an initiative to start a Bible translationprogram in every language group that needs it by the year 2025.

CONTRIBUTORSExecutive EditorsDavid A. StoopStephen F. ArterburnAssociate EditorsA. Boyd LuterConnie NealManaging EditorMark R. NortonEditorial StaffDerrick BlanchetteMeg DiehlDiane EbleBetsy ElliottAdam GraberDietrich GruenLucille LeonardPhyllis LePeauDaryl LucasJudith MorseKathy OlsonJan PigottLeanne RobertsJeremy TaylorRamona TuckerSally van der GraaffEsther WaldropKaren WalkerWightman WeesePrint BuyerTimothy BensenTypesettersJanine BollhoeferGraphic DesignerTimothy R. BottsWritersDonald E. AndersonShelly M. ChapinR. Tony CothrenShelly O. CunninghamBarry C. DavisHarold DollarJoseph M. EspinozaThomas J. FinleyWilliam J. GaultiereRonald N. GlassDaniel M. HahnEric HoeyMark W. HoffmanJohn C. HutchisonTommy A. JarrettStephen M. JohnsonG. Ted MartinezKathy McReynoldsV. Eric NachtriebConnie NealStephen L. NewmanT. Ken OberholtzerScott B. RaeRichard O. RigsbyJane E. RodgersWalter B. RussellRichard F. Travis

CONTENTSA6The Twelve StepsA8Steps for RecoveryA10The Books of the BibleA11Alphabetical Book ListingA13A Note to ReadersA15Introduction to theNew Living TranslationA21NLT Bible Translation TeamA23User’s GuideA25Preface1OLD TESTAMENT1193 NEW TESTAMENT1673Life Recovery Topical Index1726Index to Recovery Profiles1727Index to Twelve Step Devotionals1729Index to Recovery Principle Devotionals1730Index to Serenity Prayer Devotionals1731Index to Recovery Reflections

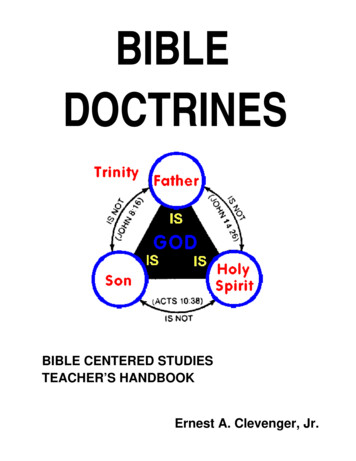

THE TWELVE STEPS1. We admitted that we were powerless over our problems—thatour lives had become unmanageable.2. We came to believe that a Power greater than ourselves couldrestore us to sanity.3. We made a decision to turn our wills and our lives over to thecare of God.4. We made a searching and fearless moral inventory of ourselves.5. We admitted to God, to ourselves, and to another humanbeing the exact nature of our wrongs.6. We were entirely ready to have God remove all these defects ofcharacter.7. We humbly asked God to remove our shortcomings.8. We made a list of all persons we had harmed and became willing to make amends to them all.9. We made direct amends to such people wherever possible,except when to do so would injure them or others.10. We continued to take personal inventory, and when we werewrong, promptly admitted it.11. We sought through prayer and meditation to improve ourconscious contact with God, praying only for knowledge of Hiswill for us and the power to carry that out.12. Having had a spiritual awakening as the result of these steps,we tried to carry this message to others and to practice theseprinciples in all our affairs.The Twelve Steps used in the Twelve Steps devotional reading plan in this Bible havebeen adapted from the Twelve Steps of Alcoholics Anonymous.

THE TWELVE STEPS OFALCOHOLICS ANONYMOUS1. We admitted we were powerless over alcohol—that our liveshad become unmanageable.2. Came to believe that a Power greater than ourselves couldrestore us to sanity.3. Made a decision to turn our will and our lives over to the careof God as we understood Him.4. Made a searching and fearless moral inventory of ourselves.5. Admitted to God, to ourselves and to another human beingthe exact nature of our wrongs.6. Were entirely ready to have God remove all these defects ofcharacter.7. Humbly asked Him to remove our shortcomings.8. Made a list of all persons we had harmed and became willingto make amends to them all.9. Made direct amends to such people wherever possible,except when to do so would injure them or others.10. Continued to take personal inventory and when we werewrong promptly admitted it.11. Sought through prayer and meditation to improve ourconscious contact with God, as we understood Him, prayingonly for knowledge of His will for us and the power to carrythat out.12. Having had a spiritual awakening as the result of these steps,we tried to carry this message to alcoholics, and to practicethese principles in all our affairs.The Twelve Steps are reprinted and adapted with permission of AlcoholicsAnonymous World Services, Inc. Permission to reprint and adapt the Twelve Stepsdoes not mean that AA has reviewed or approved the contents of this publication,nor that AA agrees with the views expressed herein. AA is a program of recoveryfrom alcoholism—use of the Twelve Steps in connection with programs and activities which are patterned after AA, but which address other problems, does notimply otherwise.

STEPS FOR RECOVERYThe 12 Steps have long been of great help to people in recovery. Much of their power comesfrom the fact that they capture principles evident in the Bible. The following chart lists the12 Steps and connects them to various Scriptures that support them. A third column ties the12 Steps to the 8 Recovery Principles of the Celebrate Recovery program. This will enable usersof this Bible who are familiar with the 8 Recovery Principles to relate quickly to content tied tothe 12 Steps.The 12 StepsHelp from the Scriptures8 Recovery PrinciplesWe admitted that wewere powerless over ourdependencies— that our lives hadbecome unmanageable.“I know that nothing good lives inme. . . . I want to do what is right,but I can’t” (Romans 7:18; see alsoJohn 8:31-36; Romans 7:14-25).Principle 1: Realize I’m not God.I admit that I am powerless tocontrol my tendency to do thewrong thing and that my life isunmanageable.We came to believe that a “God is working in you, giving youPower greater than ourselves could the desire and the power to do whatrestore us to sanity.pleases him” (Philippians 2:13; seealso Romans 4:6-8; Ephesians1:6-8; Colossians 1:21-22;Hebrews 11:1-10).Principle 2: Earnestly believe thatGod exists, that I matter to Him,and that He has the power to helpme to recover.We made a decision toturn our wills and our lives over tothe care of God.Principle 3: Consciously choose tocommit all my life and will toChrist’s care and control.“Dear brothers and sisters, I pleadwith you to give your bodies to Godbecause of all he has done for you.Let them be a living and holy sacrifice—the kind he will find acceptable” (Romans 12:1; see alsoMatthew 11:28-30; Mark10:14-16; James 4:7-10).We made a searching andfearless moral inventory of ourselves.“Let us test and examine our ways.Let us turn back to the LORD”(Lamentations 3:40; see alsoMatthew 7:1-5; 2 Corinthians7:8-10).We admitted to God, toourselves, and to another humanbeing the exact nature of ourwrongs.“Confess your sins to each other andpray for each other so that you maybe healed” (James 5:16; see alsoPsalm 32:1-5; 51:1-3; 1 John1:2-6).We were entirely ready tohave God remove all these defectsof character.“Humble yourselves before the Lord,and he will lift you up in honor”(James 4:10; see also Romans6:5-11; Philippians 3:12-14).We humbly asked God toremove our shortcomings.“If we confess our sins to him, he isfaithful and just to forgive us oursins and to cleanse us from allwickedness” (1 John 1:9; see alsoLuke 18:9-14; 1 John 5:13-15).Openly examine andconfess my faults to myself, toGod, and to someone I trust.Voluntarily submit toevery change God wants to makein my life, and humbly ask Him toremove my character defects.

The 12 StepsHelp from the Scriptures8 Recovery PrinciplesWe made a list of all thepersons we had harmed and became willing to make amends tothem all.“Do to others as you would likethem to do to you” (Luke 6:31; seealso Colossians 3:12-15; 1 John3:10-20).Evaluate all myrelationships. Offer forgivenessto those who have hurt me andmake amends for harm I’ve doneto others, except when to do sowould harm them or others.We made direct amends tosuch people wherever possible,except when to do so would injurethem or others.“If you are presenting a sacrifice atthe altar and . . . someone hassomething against you, leave yoursacrifice there at the altar. Go andbe reconciled to that person. Thencome and offer your sacrifice toGod” (Matthew 5:23-24; see alsoLuke 19:1-10; 1 Peter 2:21-25).We continued to take“If you think you are standingpersonal inventory, and when westrong, be careful not to fall”were wrong, promptly admitted it. (1 Corinthians 10:12; see alsoRomans 5:3-6; 2 Timothy 2:1-7;1 John 1:8-10).Reserve a daily timewith God for self-examination,Bible reading, and prayer in orderto know God and His will for mylife and to gain the power to follow His will.We sought throughprayer and meditation to improveour conscious contact with God,praying only for knowledge of Hiswill for us and the power to carrythat out.“Devote yourselves to prayer withan alert mind and a thankful heart”(Colossians 4:2; see also Isaiah40:28-31; 1 Timothy 4:7-8).Having had a spiritualawakening as the result of thesesteps, we tried to carry this message to others and to practicethese principles in all our affairs.“Dear brothers and sisters, ifYield myself to God toanother believer is overcome bybe used to bring this Good Newssome sin, you who are godly should to others, both by my examplegently and humbly help that person and by my words.back onto the right path. And becareful not to fall into the sametemptation yourself” (Galatians 6:1;see also Isaiah 61:1-3; Titus 3:3-7;1 Peter 4:1-5).

THE BOOKS OF THE BIBLEThe Old Testament3 Genesis77 Exodus133 Levitius171 Numbers221 Deuteronomy265 Joshua301 Judges335 Ruth343 1 Samuel387 2 Samuel425 1 Kings463 2 Kings503 1 Chronicles541 2 Chronicles587 Ezra601 Nehemiah623 Esther635 Job679 Psalms785 Proverbs823 Ecclesiastes837 Song of kukZephaniahHaggaiZechariahMalachiThe New Testament1195 Mathew1249 Mark1285 Luke1339 Romans1 Corinthians2 1 Thessalonians2 Thessalonians1 Timothy2 TimothyTitusPhilemonHebrewsJames1 Peter2 Peter1 John2 John3 JohnJudeRevelation

ALPHABETICAL LISTING OF BIBLE 1013587149731157116915771095847ActsAmos1 Chronicles2 ChroniclesColossians1 Corinthians2 1JamesJeremiahJobJoelJohn1 John2 John3 JohnJonahJoshuaJudeJudges1 Kings2 ersObadiah1 Peter2 mansRuth1 Samuel2 SamuelSong of Songs1 Thessalonians2 Thessalonians1 Timothy2 TimothyTitusZechariahZephaniah

A NOTE TO READERSThe Holy Bible, New Living Translation, was first published in 1996. It quicklybecame one of the most popular Bible translations in the English-speaking world.While the NLT’s influence was rapidly growing, the Bible Translation Committeedetermined that an additional investment in scholarly review and text refinement could make it even better. So shortly after its initial publication, the committee began an eight-year process with the purpose of increasing the level of theNLT’s precision without sacrificing its easy-to-understand quality. This secondgeneration text was completed in 2004 and is reflected in this edition of the NewLiving Translation.The goal of any Bible translation is to convey the meaning and content of theancient Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek texts as accurately as possible to contemporary readers. The challenge for our translators was to create a text that wouldcommunicate as clearly and powerfully to today’s readers as the original texts didto readers and listeners in the ancient biblical world. The resulting translation iseasy to read and understand, while also accurately communicating the meaningand content of the original biblical texts. The NLT is a general-purpose textespecially good for study, devotional reading, and reading aloud in worshipservices.We believe that the New Living Translation—which combines the latestbiblical scholarship with a clear, dynamic writing style—will communicate God’sword powerfully to all who read it. We publish it with the prayer that God willuse it to speak his timeless truth to the church and the world in a fresh, new way.The PublishersJuly 2004

INTRODUCTION TO THENEW LIVING TRANSLATIONTranslation Philosophy and MethodologyEnglish Bible translations tend to be governed byone of two general translation theories. The firsttheory has been called “formal-equivalence,”“literal,” or “word-for-word” translation. According to this theory, the translator attempts torender each word of the original language intoEnglish and seeks to preserve the original syntaxand sentence structure as much as possible intranslation. The second theory has been called“dynamic-equivalence,” “functional-equivalence,”or “thought-for-thought” translation. The goal ofthis translation theory is to produce in Englishthe closest natural equivalent of the messageexpressed by the original-language text, both inmeaning and in style.Both of these translation theories have theirstrengths. A formal-equivalence translation preserves aspects of the original text—includingancient idioms, term consistency, and originallanguage syntax—that are valuable for scholarsand professional study. It allows a reader to traceformal elements of the original-language textthrough the English translation. A dynamicequivalence translation, on the other hand,focuses on translating the message of theoriginal-language text. It ensures that the meaning of the text is readily apparent to the contemporary reader. This allows the message to comethrough with immediacy, without requiringthe reader to struggle with foreign idioms andawkward syntax. It also facilitates serious studyof the text’s message and clarity in both devotional and public reading.The pure application of either of these translation philosophies would create translations atopposite ends of the translation spectrum. But inreality, all translations contain a mixture of thesetwo philosophies. A purely formal-equivalencetranslation would be unintelligible in English,and a purely dynamic-equivalence translationwould risk being unfaithful to the original.That is why translations shaped by dynamicequivalence theory are usually quite literal whenthe original text is relatively clear, and the translations shaped by formal-equivalence theory aresometimes quite dynamic when the original textis obscure.The translators of the New Living Translationset out to render the message of the original textsof Scripture into clear, contemporary English. Asthey did so, they kept the concerns of bothformal-equivalence and dynamic-equivalence inmind. On the one hand, they translated as simply and literally as possible when that approachyielded an accurate, clear, and natural Englishtext. Many words and phrases were rendered literally and consistently into English, preservingessential literary and rhetorical devices, ancientmetaphors, and word choices that give structureto the text and provide echoes of meaning fromone passage to the next.On the other hand, the translators renderedthe message more dynamically when the literalrendering was hard to understand, was misleading, or yielded archaic or foreign wording. Theyclarified difficult metaphors and terms to aid inthe reader’s understanding. The translators firststruggled with the meaning of the words andphrases in the ancient context; then they rendered the message into clear, natural English.Their goal was to be both faithful to the ancienttexts and eminently readable. The result is atranslation that is both exegetically accurate andidiomatically powerful.Translation Process and TeamTo produce an accurate translation of the Bibleinto contemporary English, the translation teamneeded the skills necessary to enter into thethought patterns of the ancient authors and thento render their ideas, connotations, and effectsinto clear, contemporary English. To begin thisprocess, qualified biblical scholars were needed tointerpret the meaning of the original text and tocheck it against our base English translation. Inorder to guard against personal and theologicalbiases, the scholars needed to represent a diversegroup of Evangelicals who would employ the bestexegetical tools. Then to work alongside thescholars, skilled English stylists were needed toshape the text into clear, contemporary English.With these concerns in mind, the Bible Translation Committee recruited teams of scholars thatrepresented a broad spectrum of denominations,theological perspectives, and backgrounds withinthe worldwide Evangelical community. (Thesescholars are listed at the end of this introduction.) Each book of the Bible was assigned tothree different scholars with proven expertise inthe book or group of books to be reviewed. Eachof these scholars made a thorough review of a

Page A16 /INTRODUCTION TO THE NEW LIVING TRANSLATIONbase translation and submitted suggested revisions to the appropriate Senior Translator. TheSenior Translator then reviewed and summarizedthese suggestions and proposed a first-draft revision of the base text. This draft served as the basisfor several additional phases of exegetical andstylistic committee review. Then the Bible Translation Committee jointly reviewed and approvedevery verse of the final translation.Throughout the translation and editing process, the Senior Translators and their scholarteams were given a chance to review the editingdone by the team of stylists. This ensured thatexegetical errors would not be introduced late inthe process and that the entire Bible TranslationCommittee was happy with the final result. Bychoosing a team of qualified scholars and skilledstylists and by setting up a process that allowedtheir interaction throughout the process, theNew Living Translation has been refined to preserve the essential formal elements of the originalbiblical texts, while also creating a clear, understandable English text.The New Living Translation was first publishedin 1996. Shortly after its initial publication, theBible Translation Committee began a process offurther committee review and translation refinement. The purpose of this continued revision wasto increase the level of precision without sacrificing the text’s easy-to-understand quality. Thissecond-edition text was completed in 2004, andthis printing of the New Living Translationreflects the updated text.the Greek New Testament, published by the UnitedBible Societies (UBS, fourth revised edition,1993), and Novum Testamentum Graece, edited byNestle and Aland (NA, twenty-seventh edition,1993). These two editions, which have the sametext but differ in punctuation and textual notes,represent, for the most part, the best in moderntextual scholarship. However, in cases wherestrong textual or other scholarly evidence supported the decision, the translators sometimeschose to differ from the UBS and NA Greek textsand followed variant readings found in otherancient witnesses. Significant textual variants ofthis sort are always noted in the textual notes ofthe New Living Translation.Written to Be Read AloudIt is evident in Scripture that the biblical documents were written to be read aloud, often inpublic worship (see Nehemiah 8; Luke 4:16-20;1 Timothy 4:13; Revelation 1:3). It is still the casetoday that more people will hear the Bible readaloud in church than are likely to read it forthemselves. Therefore, a new translation mustcommunicate with clarity and power when it isread publicly. Clarity was a primary goal for theNLT translators, not only to facilitate privatereading and understanding, but also to ensurethat it would be excellent for public reading andmake an immediate and powerful impact on anylistener. We have converted ancient weights and measures (for example, “ephah” [a unit of dryvolume] or “cubit” [a unit of length]) to modern English (American) equivalents, since theancient measures are not generally meaningfulto today’s readers. Then in the textual footnotes we offer the literal Hebrew, Aramaic, orGreek measures, along with modern metricequivalents. Instead of translating ancient currency valuesliterally, we have expressed them in commonterms that communicate the message. Forexample, in the Old Testament, “ten shekelsof silver” becomes “ten pieces of silver” toconvey the intended message. In the NewTestament, we have often translated the“denarius” as “the normal daily wage” to facilitate understanding. Then a footnote offers:“Greek a denarius, the payment for a full day’swage.” In general, we give a clear English rendering and then state the literal Hebrew, Aramaic, or Greek in a textual footnote. Since the names of Hebrew months areunknown to most contemporary readers, andsince the Hebrew lunar calendar fluctuatesfrom year to year in relation to the solar calendar used today, we have looked for clear waysto communicate the time of year the Hebrewmonths (such as Abib) refer to. When anexpanded or interpretive rendering is given inThe Texts behind the New Living TranslationThe Old Testament translators used the MasoreticText of the Hebrew Bible as represented in BibliaHebraica Stuttgartensia (1977), with its extensivesystem of textual notes; this is an update ofRudolf Kittel’s Biblia Hebraica (Stuttgart, 1937).The translators also further compared the DeadSea Scrolls, the Septuagint and other Greekmanuscripts, the Samaritan Pentateuch, the Syriac Peshitta, the Latin Vulgate, and any other versions or manuscripts that shed light on themeaning of difficult passages.The New Testament translators used the twostandard editions of the Greek New Testament:Translation IssuesThe translators have made a conscious effort toprovide a text that can be easily understood bythe typical reader of modern English. To this end,we sought to use only vocabulary and languagestructures in common use today. We avoidedusing language likely to become quickly dated orthat reflects only a narrow sub-dialect of English,with the goal of making the New Living Translation as broadly useful and timeless as possible.But our concern for readability goes beyondthe concerns of vocabulary and sentence structure. We are also concerned about historical andcultural barriers to understanding the Bible, andwe have sought to translate terms shrouded inhistory and culture in ways that can be immediately understood. To this end:

I N T R O D U C T I O N T O T H E N E W L I V I N G T R A N S L AT I O N / Page A17 the text, a textual note gives the literal rendering. Where it is possible to define a specificancient date in terms of our modern calendar,we use modern dates in the text. A textualfootnote then gives the literal Hebrew dateand states the rationale for our rendering. Forexample, Ezra 6:15 pinpoints the date whenthe post-exilic Temple was completed in Jerusalem: “the third day of the month Adar.” Thiswas during the sixth year of King Darius’sreign (that is, 515 B.C.). We have translatedthat date as March 12, with a footnote givingthe Hebrew and identifying the year as515 B.C.Since ancient references to the time of day differ from our modern methods of denotingtime, we have used renderings that areinstantly understandable to the modernreader. Accordingly, we have rendered specifictimes of day by using approximate equivalentsin terms of our common “o’clock” system. Onoccasion, translations such as “at dawn thenext morning” or “as the sun began to set”have been used when the biblical reference ismore general.When the meaning of a proper name (or awordplay inherent in a proper name) is relevant to the message of the text, its meaning isoften illuminated with a textual footnote. Forexample, in Exodus 2:10 the text reads: “Theprincess named him Moses, for she explained,‘I lifted him out of the water.’ ” The accompanying footnote reads: “Moses sounds like aHebrew term that means ‘to lift out.’ ”Sometimes, when the actual meaning of aname is clear, that meaning is included inparentheses within the text itself. For example,the text at Genesis 16:11 reads: “You are toname him Ishmael (which means ‘God hears’),for the LORD has heard your cry of distress.”Since the original hearers and readers wouldhave instantly understood the meaning of thename “Ishmael,” we have provided modernreaders with the same information so they canexperience the text in a similar way.Many words and phrases carry a great deal ofcultural meaning that was obvious to the original readers but needs explanation in our ownculture. For example, the phrase “they beattheir breasts” (Luke 23:48) in ancient timesmeant that people were very upset, often inmourning. In our translation we chose totranslate this phrase dynamically for clarity:“They went home in deep sorrow.” Then weincluded a footnote with the literal Greek,which reads: “Greek went home beating theirbreasts.” In other similar cases, however, wehave sometimes chosen to illuminate theexisting literal expression to make it immediately understandable. For example, here wemight have expanded the literal Greek phraseto read: “They went home beating their breastsin sorrow.” If we had done this, we would not have included a textual footnote, since the literal Greek clearly appears in translation.Metaphorical language is sometimes difficultfor contemporary readers to understand, so attimes we have chosen to translate or illuminate the meaning of a metaphor. For example,the ancient poet writes, “Your neck is like thetower of David” (Song of Songs 4:4). We haverendered it “Your neck is as beautiful as thetower of David” to clarify the intended positive meaning of the simile. Another examplecomes in Ecclesiastes 12:3, which can be literally rendered: “Remember him . . . when thegrinding women cease because they are few,and the women who look through the windows see dimly.” We have rendered it:“Remember him before your teeth—your fewremaining servants—stop grinding; and beforeyour eyes—the women looking through thewindows—see dimly.” We clarified such metaphors only when we believed a typical readermight be confused by the literal text.When the content of the original languagetext is poetic in character, we have rendered itin English poetic form. We sought to breaklines in ways that clarify and highlight therelationships between phrases of the text.Hebrew poetry often uses parallelism, a literaryform where a second phrase (or in someinstances a third or fourth) echoes the initialphrase in some way. In Hebrew parallelism,the subsequent parallel phrases continue,while also furtheri

2. Came to believe that a Power greater than ourselves could restore us to sanity. 3. Made a decision to turn our will and our lives over to the care of God as we understood Him. 4. Made a searching and fearless moral inventory of ourselves. 5. Admitted to God, to ourselves and