Transcription

A Tale of Two Diets: What Can We Learn From the Diet Wars?Dawn Larsen and Margaret Murray-DavisAbstractDuring the last two decades, obesity rates in the UnitedStates have escalated dramatically, and intense mediacoverage of obesity issues has fueled consumer interest inlow-carbohydrate diets designed to promote rapid weightloss. The food industry has fostered the assumption that adrop in carbohydrate consumption will translate into a dropin weight. Studies of low-carbohydrate dieters, however,have indicated that weight loss is due primarily to caloriereduction rather than carbohydrate restriction. When lowfat foods were heavily promoted, dieters assumedconsumption of reduced-fat or fat-free foods would result inweight loss, unaware that calorie consumption could increaseeven if fat intake was reduced. This pattern is likely to berepeated if escalating consumption of low-carbohydratefoods translates into increased calorie intake. Once polarized,low-fat and low-carbohydrate advocates, as well as healthprofessionals, have moved toward agreement on a numberof critical points designed to promote weight loss as well asto prevent chronic disease. These groups recommend a dietrich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, low-fat dary products,lean meats, poultry, and fish. Despite this congruence, theweight loss industry aggressively continues to market newdiets, products, and services. Ironically, as the diet businessbecomes more profitable, obesity rates continue to climb inthe United States.During the last two decades, obesity rates in the UnitedStates have escalated dramatically among children,adolescents, and adults. Over two thirds of all adults areoverweight and half of these qualify as clinically obese(Mokdad, Serdula, & Dietz, 1999; Hill, Goldberg, Pate, &Peters, 2001). A recent Report on Overweight and Obesityfrom the Surgeon General's Office noted that 69% of Blackwomen and 58% of Black men were overweight or obese.Among Hispanic adults, the rates are 69% of men and 70%of women. These rates are slightly higher than those in thewhite population, in which 62% of men and 47% of womenare overweight or obese (U.S. Department of Health andHuman Services [USDHHS],2004).* Dawn Larsen, PhD,CHES; Minnesota State University, HealthScience Department, 213 Highland Center North, Mankato,MN 56001; Telephone: 507-389-2113; E-mail:m.larsen@rnnsu.edu;Chapter: Beta KappaMargaret Murray-Davis, PhD;Minnesota State University, HealthScience Department, 213 Highland Center North, Mankato,MN 56001* CorrespondingObesity is not simply an aesthetic problem, though itmay be a source of frustration for many who are concernedabout their appearance. Excess weight is a significant riskfactor for leading causes of morbidity and mortality in theUnited States, such as heart disease, stroke, hypertension,diabetes, and cancer (Allison, Fontaine, Manson, Stevens,& Vantalie, 1999). The cost for obesity-related medicaltreatment, currently estimated at 1 17 billion, is expected tocontinue climbing, and it has been suggested that poor diet,combined with physical inactivity, may overtake tobacco asthe leading cause of preventable death in the United States(Mokdad, Marks, Stroup, & Gerberding, 2004).In the last 25 years, the prevalence of overweight hasdoubled in young children and tripled in adolescents (Ogden,Hegal, Carroll, & Johnson, 2002). Today 15% of children 618 exceed the upper limit of healthy weight for their agegroups. As with adults, the number is higher among Blackand Latino children, averaging 26% (Schmidt, 2003).Overweightchildren are often stigmatizedby peers and sufferfrom low self-esteem and depression (Davison & Birch, 2001;Eisenberg, Neumark-Sztainer, & Story, 2003; Strauss, 2000;Strauss & Pollack, 2003). In addition, obesity and excessweight in children can lead to a range of debilitating healthproblems, such as type 2 diabetes, hypertension, andcardiovascular disease. Nearly one million obese Americanchildren suffer from metabolic syndrome, a condition thatsubstantially increases their risk of type 2 diabetes andpremature heart disease (Cook, Weitzman, Auinger, Nguyen,& Deitz, 2003). Obese children are also more likely to becomeobese adults, and childhood risk factors are increasinglylinked to the incidence of adult disease. Harvard MedicalSchool released a study concluding that prevention ofobesity in childhood could have a "lifelong, perhapsmultigenerational impact" (Oken & Gillman, 2003, p. 496).Medical and public health professionals have warnedabout the growing obesity epidemic for some time. Recentintense media coverage of obesity issues has fueled thealready intense public interest in dietary regimens designedto promote easy, rapid, convenient, hunger-free weight lossinvolving a minimum amount of effort. Unfortunately, manydieters view weight loss as an aesthetic issue and perhapssecondarily as a disease prevention strategy. Many willchoose diets that produce quick results but are nutritionallyunsound. Media promotion and diet gimmicks drive theproblem. A national poll conducted by the Opinion DynamicsCorporation (2004) indicated that 11% of Americans arecurrently on a rigorous low-carbohydratediet, and millionsmore focus on restricting their carbohydrate intake. Twentypercent of the public has tried such a diet in the past twoauthorThe Health EducatorSpring 2005, Vol. 37, No. 1

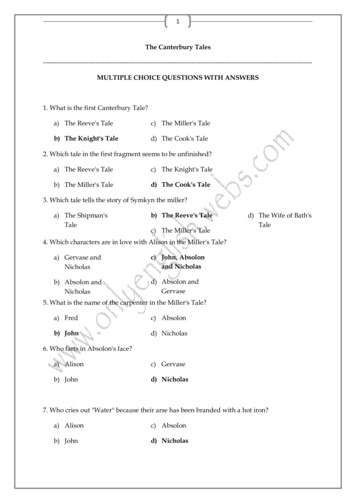

years, and nearly 20% who are not currently on a lowcarbohydrate diet may try one in the next two years.Low-CarbohydrateDietsexpected to spend about 85 each month on reducedcarbohydratefoods (Kadlec, 2004). The industry is so strongthat it has generated a new trade publication, Lowcarbiz.Unfortunately, the ubiquity of "low-carb" advertising isencouraging both dieters and non-dieters to eat lowcarbohydrate foods, resulting in a nutritional minefield to benavigated by consumers.HistoryDramatically restricting carbohydrate consumptionappeared to be a revolutionary way of losing weight when itwas first promoted by Dr. Robert Atkins in 1972. It allowed Consumer IssuesMarketing of these diets relies heavily on flaweddieters to eat as much as they wanted, whenever they werehungry, avoiding the gnawing hunger and cravings concepts, skillfully manipulated nutritional distortions, andassociated with traditional low-fat, restricted-calorie diets. catchy "buzzwords" to attract consumers. A number of newThe only caveat was that carbohydrate consumption was terms and claims may be confusing and deceptive. Amongcarefully monitored and curtailed. However, Atkins was not the most pervasive are the terms "low-carbohydrate," "carbthe first to promote a low-carbohydrate diet. In the late 19th smart," "carb-aware," "impact carb," and "low-carb lifestyle,"century, William Banting (1869) encouraged carbohydrate which imply that eating foods with these labels will reducereduction in a book titled A Letter on Corpulence,Addressed carbohydrate consumption. The legality of low-carbohydrateto the Public. Banting was dismissed as a quack by claims is questionable, since the Food and Drugmainstream nutrition authorities. Atkins' theories were also Administration prohibits claims about nutrients that havederided initially, and most health professionals advocated a not been defined. Most manufacturers do not offerlow-fat diet to reduce weight as well as the risk of heart comparisons of "regular" and "low-carbohydrate" foods todisease and cancer, the two leading causes of death in the back up their claims. Many "low-carbohydrate" foodsUnited States.actually do not have fewer carbohydrates than the originalAlthough Atkins had advocates for nearly 30 years, it food, but they may be promoted as having fewer "net carbs.was not until fairly recently that low-carbohydrate diets The term "net carbohydrate" was created by the foodbecame ubiquitous. Their popularity was fueled by industry to define carbohydrates that affect insulin levels.preliminary research that appeared to contradict long- This is a reference to the glycemic index, which is a criticalstanding concerns that the fat-laden Atkins diet would cause component of several diet books, such as The Zone, Dr.a potentially dangerous rise in cholesterol levels, increasing Atkins New Diet Revolution, Good Carbs, Bad Carbs, andthe risk of cardiovascular disease among low-carbohydrate The New Glucose Revolution. The glycemic index is adieters (Stern et al., 2004; Yancy, Olsen, Guyton, Bakst, & ranking of how much and how fast certain "whole" foodsWestman, 2004).increase blood sugar and trigger the production of insulin,which helps supply sugar to cells for energy use. FoodsPremisewith a high glycemic value are thought to be absorbed faster,Most low-carbohydrate diets are based on same premise; resulting in rapid fluctuations in insulin levels. This triggers"bad" carbohydrates are to be avoided in the process of an energy boost, followed by hunger and fatigue. A growinglosing weight or avoiding weight gain. Diet books like DI: body of research suggests that diets promoting low glycemicAtkins' New Diet Revolution, The South Beach Diet, The foods not only improve cardiovascular risk factors, but alsoZone, and Good Carbs, Bad Carbs advocate limiting may help in weight control. In addition, low glycemic foodsconsumption of "bad" carbohydrates such as refined flours, help to avoid frequent and rapid swings in sugar and insulinsugars, and starchy vegetables such as potatoes. The diets levels, which are suspected to lead to insulin resistance andare based on the premise that "bad" carbohydrates cause a diabetes (Jenkins et al, 2002; Ludwig, 2002).rapid spike in blood sugar, which raises blood insulin levels.It is critical to note that research on the glycemic indexThis process causes weight gain by promoting fat storage, has been based primarily on the consumption of "wholeincreasing hunger by causing a drop in blood sugar, or both. foods." However, the food industry has extended,To short circuit this pattern, the low-carbohydratediets often manipulated, and in many ways distorted this information inadvocate consumption of protein, fat, and "good" attempting to market processed foods. The number of "netcarbohydrates like whole grains and vegetables.carbs" or "impact carbs" is obtained by subtracting theThe enthusiasm for low-carbohydrate diets has number of grams of carbohydratederived from nutrients likeproduced a proliferation of new diet books, food products, sugar alcohols and fiber, alleged to "have a minimal impactspecialty foods, and nutritional supplements. As a on blood sugar," from the total number of carbohydrateconsequence, the low-carbohydrate phenomenon has grams in a food serving (Atkins, 2002). There is little evidencebecome a powerful force in the national economy as well as to support the theory that foods sweetened with sugarthe national conscience. In just two years, over 1,500 new alcohols or substitutes do not raise blood sugar. Muffins orlow-carbohydratefoods and beverages were introduced, and cake sweetened with sugar substitutes have been found tosales of low-carbohydrateproducts are expected to total 30 raise blood sugar as much as those containing sugar (Fosterbillion in 2004. Each carbohydrate-conscious consumer is Powell, Holt, & Brand-Miller, 2002).Spring 2005,Vol. 37, No. 1The Health Educator

Unfortunately, a rapidly expanding low-carbohydrateindustry promotes the assumption that a drop in carbohydrateconsumption will translate into a drop in weight. Many foodslow in carbohydrate, or "net carbs," are high in both caloriesand fat, associated with higher risk of heart disease andcancer as well as excess weight (Hu, & Willett, 2002;Lieberman, Prindiville, Weiss, & Willett, 2003). What manydieters fail to realize is that if they consume as many or morecalories than they expend, even on a low-carbohydrate diet,they will maintain or gain weight rather than losing it. Thefew controlled studies of low-carbohydrate dieters have, infact, indicated that weight loss is due primarily to caloriereduction rather than carbohydrate restriction (Bravata etal., 2003).The effect on consumer behavior appears to be similarto what happened when low-fat foods were heavilypromoted. When extreme fat restriction was advocated,dieters assumed unlimited consumption of reduced-fat orfat-free foods would result in weight loss or prevent weightgain. In the two decades between 1970 and 1990,Americansdecreased intake of total fat from about 37% of calories to34% of calories. However, as consumers indulged in low-fatproducts the average adult calorie intake increased by about300 calories during the same time period. Because totalcalorie consumption increased, fat intake actually increasedfrom 81 grams per day to 83 grams per day, contributing tothe nation's collective weight gain during this time period(Briefel & Johnson, 2004). This pattern is likely to be repeatedif escalating consumption of low-carbohydrate foodstranslates into increased calorie intake.Low-Fat DietsThe most prominent of many low-fat advocates iscardiologistDean Omish, Director of the PreventiveMedicineResearch Institute. Ornish originally supported a very-lowfat diet, which included abundant quantities of fruits,vegetables, and whole grains, and derived 70% to 75% of itscalories from carbohydrate (Ornish, 1996). This carbohydratelevel was higher than the level recommended by a number ofpublic health organizations, such as the American HeartAssociation and the National Academy of Sciences. It wasthought that too many carbohydrates would raisetriglycerides and lower HDL cholesterol.However, this did not happen when Ornish monitored35 people on his recommended diet for five years. This dietappeared to achieve an actual reduction in coronaryocclusion in people who reduced fat intake to just 10% perday (Ornish et al, 1998). Critics charged that this may havebeen related to other facets of Ornish's program, such asvigorous exercise, stress reduction, and weight loss, butuntil Ornish's research was published, reversal of heartdisease was only thought possible through surgery. Incontrast, proponents of low-carbohydrate diets have notpublished longitudinal studies showing their long termeffects on heart health.There seems to be little argument that low-carbohydratediets are effective for fairly rapid weight loss. Experts whoevaluated over 35 years of research indexed in MEDLINEfound that weight loss while using low-carbohydrate dietswas principally associated with decreased calorie intakeand duration of the diet but not with reduced carbohydrateintake. No studies have demonstrated that low-carbohydratediets are safe or effective for use over long periods of time(Blackbum, 2002; Bravata et al., 2003; Foster et al, 2003;Westman & Volek, 2002).Points of ConsensusConsumers are the ones who benefit least whenconflicting theories struggle for public acceptance. Mostfad diets rely on gimmicks or "hooks" which may betemporarily appealing but seem, and often are, too good tobe true. Many people, however, want practical informationthat is useful for long-term weight loss and maintenance,which carries aesthetic as well as health benefits. Lowcarbohydrate and low-fat regimens would seem to be atopposite ends of the diet spectrum, but even icons like Omishand the Atkins program are cautiously moving closer to thecenter, modifying their initial recommendations of over aquarter of a century ago. Ornish (2004) has acknowledgedthe importance of limiting consumption of refined ("bad")carbohydrates and Atkins advocates have acknowledgedthe importance of adding fruits and vegetables ("good")carbohydrates to the diet (Atkins, 2002). Most healthprofessionals continue to support the idea that long-term,health-promoting weight loss is most successful when itresults from a reduced calorie diet that is low in fat and highin vegetables, fruits, and whole grains. In keeping with thispremise, a number of critical points of agreement haveemerged among nutrition experts, many of whom recentlyparticipated in a national summit on obesity sponsored bythe Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (2004). Thisconsensus is supported by the most recent DietaryGuidelinesfor Americans issued by the USDHHS and U.S.Department of Agriculture (USDA) (2005).1. Consume fewer "bad" carbohydrates with a high contentof sugar and refined flour (Atkins, 2002; Ornish, 2004;USDHHS and USDA Press Conference, 2005). These itemstend to be low in fiber and high in calories. This means theyare absorbed quickly, causing a rapid rise in blood sugar andaccompanyinginsulin spike, which may promote weight gain.2. Consume more "good" carbohydrates like fruits,vegetables, legumes, and whole grains. Their high fibercontent promotes satiety, helping to control appetite. Theyare also rich in micronutrientsthat help prevent heart diseaseand cancer (Liu et al., 1999; Osagian et al., 2003; USDHHSand USDA, 2005). Consuming them thus has a doublebenefit.The Health EducatorSpring 2005, Vol. 37, No. 1

3. Consume fewer calories. Perhaps the most fundamentalconcept of weight loss is that calories do count, whether thediet is low-fat or low-carbohydrate. Following a regimen thatreduces portions or excludes broad categories of foodgenerally results in calorie reduction, which promotes weightloss. Because fat has nine calories per gram and protein andcarbohydrate have only four, eating less fat can actuallyresult in calorie reduction even if food intake stays constant.So eating less fat and fewer simple carbohydrates is a goodidea.fruits, vegetables, legumes, and whole grains have diseasefighting properties with the potential to prevent a number ofchronic diseases, including cancer (Hu & Willette, 2002;Newmark et al. 1999). They are not present in meats andanimal products, the basis of many high-protein diets.Successful Weight LossWhile there is not much scientific evidencefor or againstthe use of low-carbohydrate diets, most existing studiesindicate weight loss occurred when study participants were4. Include exercise, which is critical for weight loss success on the diets for longer periods, and when they ate fewerand maintenance (USDHHS and USDA, 2005). Dieters who calories. This may indicate that certain dietary patterns, suchengage in regular exercise are not only more likely to lose as a low-carbohydrate approach, make it easier for people toweight, but are far more successful in keeping weight off for adhere to a lower-calorie diet. A low-fat diet, however, alsoat least a year (Pavlou, Krey & Steffee, 1989). In addition, promotes weight loss, because dieters inadvertently eat fewerthose who lose weight by dieting need to eat less food (or calories. One of the most relevant contributions of the currentexercise more) to sustain weight loss, because compensatory diet debate may be the acknowledgment that the same dietmetabolic processes resist the maintenance of lowered body may not work for everyone with respect to initial weightweight (L.eibe1, Rosenbaum, & Hirsh, 1995).loss. Low-carbohydratediets do seem to promote short-termweight loss. People on low-carbohydrate diets, however, are5. Reduce consumption of red meat. It is a primary source of very rare among the 3,000 subjects in the National Weightsaturated fat in the diet, which has been linked to both heart Loss Registry who have lost at least 30 pounds and kept thedisease and cancer (Hu & Willette, 2002; Omish, 2004). weight off for at least six years (Klem, Wing, McGuire, Seagle,Excessive protein consumption (especially animal protein, & Hill, 1997). A low-fat diet also aided weight loss for 3,200like red meat) may also increase the risk for osteoporosis in participants in a six-year study related to the Diabeteswomen because the body takes calcium from the bone to Prevention Program (Diabetes Prevention Program Researchneutralize the acids that build up in the blood as a result of Group, 2002).digesting large amounts of protein (Massey, 2003).Future Initiatives6. Consume "good" fats like omega-3 fatty acids every dayMost public health and medical professionals advocateor at least twice a week. These are usually found in fatty fishlike salmon, and as little as three grams a day may cut risk of more research on the prevention and treatment of obesity.cardiac death by nearly 80%, lower triglycerides, reduce Meanwhile, they recommend an overall healthy dietaryinflammation, and help prevent cancer (Hu & Willette, 2002). pattern that is rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, lowfat dairy products, lean meats, poultry, and fish. These7. Choose quality over quantity. Eventually, small portions recommendations are strikingly similar to the tenets sharedof higher quality foods may become more satisfying than by the low-fat and low-carbohydrate advocates. Despite thislarger portions of junk food. What is included in the diet is congruence, the weight loss industry aggressively continuesequally as important as what is excluded.to market new diets, products, and services. Ironically, asthe diet business becomes more profitable, obesity rates8. Attempt to lose weight in ways that enhance health rather continue to climb in the United States.than harming it. Weight loss can be achieved through theSecretary of Agriculture Ann Veneman (USDHHS anduse of stimulants like amphetamines, diet drugs such as USDA, 2005) has noted that maintenance programs of mostephedra, or even through the use of tobacco products as popular diet programs are consistent in many ways with theappetite suppressants. However, under most circumstances 2005 Dietary Guidelines. The task for health educators is tothe potential negative effects of these strategies far outweigh design messages to help consumers understand the extentthe benefits of weight loss.and strength of this consistency. This is critical fordecontextualizing the unrealistic claims and expectations9. Base a diet on whole foods rather than supplements. associated with popular diet programs. Tommy Thompson,Because low-carbohydrate diets restrict many foods and food former Secretary of Health and Human Services, noted thatgroups, supplements are frequently recommended, leading the new Dietary Guidelines are a "solid combination ofconsumers to believe that supplements can substitute for research science and common sense. .a prescription thatfood. An increasing body of research has isolated thousands we can write for ourselves, fill in for ourselves, and be happierof substances known as phytochemicals, which are and healthier for it" (USDHHS and USDA, 2005, p. 3). Perhapsimpossible to synthesize in a pill. Phytochemicals found in the greatest challenge for health educators is to helpSpring 2005, Vol. 37, No. 1The Health Educator

consumers write and follow prescriptions that will helpmitigate the obesity epidemic in the United States.Jenkins, D. J., Kendal, C. W., Augustin, L. S., Franceschi, S.,Hamidi, M., & Marchie, et.al. (2002). Glycemic index:Overview of implications in health and disease. AmericanJournal of Clinical Nutrition, (76)1, 2668-273s.ReferencesKadlec, D. (2004, May 3). The low-carb frenzy. E m , 163,4654.Allison, D. B., Fontaine, K. R., Manson, J. E., Stevens, J., & Klem, M. L., Wing, R. R., McGuire, M. T., Seagle, H. M., &Vantalie, T. B. (1999). Annual deaths attributable toHill, J. 0. (1997). A descriptive study of individualsobesity in the United States. Journal of the Americansuccessful at long-term maintenance of substantialMedical Association, 282, 1530-1538.weight loss. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition,Atkins, R. C. (2002). Dr. Atkins' new diet revolution. New66,239-246.York: Harper Collins.Liebel, R. L., Rosenbaum, M., & Hirsch, J. (1995). Changes inBanting, W. (1869). Letter on corpulence, addressed to theenergy expenditure resulting from altered body weight.public. (4th ed.). Retrieved August 5,2004, from http://New England Journal of Medicine, 332(10), man, D. A., Prindiville, S., Weiss, D. G., & Willett, W.Blackburn, G. I. (2002). Making good decisions abut diet.(2003). Risk factors for advanced colonic neoplasia andWeight loss is not weight maintenance. Clevelandhyperplastic polyps in asymptomatic individuals.Clinic Journal of Medicine, 69, 864-866.Journal of the American Medical Association, 290,Bravata, D. M., Sanders, L., Huang, J., Krumholz, H. M.,2959-2967.Ollcin, I., Gardner, C. D., et al. (2003). Efficacy and safety Liu, S., Stampfer, M. J., Hu, F. B., Giovannucci,E. R., Manson,of low-carbohydrate diets. Journal of the AmericanJ. E., Hennekens, et al. (1999). Whole-grain consumptionMedical Association, 289, 1837-1850.and risk of coronary heart disease: Results from theBriefel, R. &Johnson, C. L. (2004). Secular trends in dietaryNurse's Health Study. American Society for Clinicalintake in the United States.Annual Review ofNutrition,Nutrition, 70(3), 412-419.24,401-431.Ludwig, D. S. (2002). The glycemic index: PhysiologicalCook, S., Weitzman, M., Auinger, P., Nguyen, M., & Deitz,mechanisms relating to obesity, diabetes, andW. H. (2003). Prevalence of a metabolic syndromecardiovascular disease. Journal of the Americanphenotype in adolescents: Findings from Third NationalMedical Association, 287,2414-2423.Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988-1994. Massey L. K. (2003). Dietary animal and plant protein andArchives of Pediatrics Adolescent Medicine, 157, 821human bone health: A whole foods approach. Journal827.ofNutrition, 133,8623-865s.Davison, K. K. & Birch, L. L. (2001). Weight status, parent Mokdad, A. H., Serdula, M. K., & Dietz, W. H. (1999). Thereaction, and self-concept in five-year-old girls.spread of the obesity epidemic in the United States,Pediatrics, 107(1), 46-53.1991- 1998. Journal of the American MedicalDiabetes Prevention Program Research Group. (2002).Association, 282,15 19-1522.Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with Mokdad, A. H., Marks, J. S., Stroup, D. F., & Gerberding, J.lifestyle intervention or Metformin. New EnglandL. (2004). Actual causes of death in the United States.Journal of Medicine, 346,393-403.Journal of the American Medical Association, 291,Eisenberg, M. E., Neumark-Sztainer,D., & Story, M. (2003).1238-1245.Associations of weight-based teasing and emotional Newmark, H., Wittkowski, K. M., Shiff, S. J., Hirsch J., Holmeswell-being among adolescents. Archives of PediatricM.D., Rosner, B., et al. (1999). Dietary fat and risk ofand Adolescent Medicine, 157,733-738.breast cancer. Journal of the American MedicalFoster, G D., Wyatt, H. R., Hill, J. O., McGuckin, B. G, Brill,Association, 282,1223- 1224.C., Mohammed, B. S., et al. (2003). A randomized trial of Ogden C. L., Flegal, K. M., Carroll, M. D., &Johnson, C. L.a low-carbohydrate diet for obesity. New England(2002). Prevalence and trends in overweight among USJournal of Medicine, 348,2082-2090.children and adolescents, 1999-2000. Journal of theFoster-Powell, K., Holt, S. A., & Brand-Miller, J. (2002).American Medical Association, 288, 1728-1732.International table of glycemic index and glycemic load Oken, E., & Gillman, M. (2003). Fetal origins of obesity.values: 2002. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition,Obesity Research, 11,496-506.76(1), 5-56.Opinion Dynamics Corporation. (2004, July). Updated lowHill, J. O., Goldberg, J., Pate, R., & Peters, J. (2001).carb results. Retrieved October 6, 2004 from: http://Introduction to special issue. Nutrition Reviews, 59,www.opiniondynamics.comflowcarb.htmls4-s6, 5 7 - 6 2 .Omish, D. (1996). Dr. Dean Ornish'sprogram for reversingHu, F. B. & Willett, W. C. (2002). Optimal diets for preventionheart disease. New York: Ballentine Books.of coronary heart disease. Journal of the American Omish, D. (2004, June 21). The Atkins Ornish South BeachMedical Association, 288,2569-2578.Zone diet. Time, 163,62.The Health EducatorSpring 2005, Vol. 37, No. 1

Ornish, D., Schenvitz, L. W., Billings, J. H., Gould, K. L., Strauss, R, & Pollack, H. (2003). Social marginalization ofMerritt, T. A., Sparler, S., et al. (1998). Intensive lifestyleoverweight children. Archives of Adolescent andPediatric Medicine, 157,746-752.changes for reversal of coronary heart disease. Journalof the American Medical Association, 280,2001-2007. Strauss, R. S. (2000). Childhood obesity and self-esteem.Pediatrics, 105(1), e l 5Osagian, S. K., Stampfer, M. J., Rimm, R., Spiegelman, D.,Manson, J. E., & Willett, W. (2003). Dietary carotenoids U.S. Department of Health and Human Services andand risk of coronary artery disease in women. AmericanU. S. Department of Agriculture Press Conference (2005).Society for Clinical Nutrition, 77(6), 1390-1399.Announcement of the new dietary guidelines forAmericans. Retrieved January 12, 2005 from http://Pavlou, K. N., Krey, S. & Steffee,W. P. (1989). Exercise as anwww.health.gov/dietaryguidelines/dga2005/adjunct to weight loss and maintenance in moderatelytranscript.htrnobese subjects. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition,49 (Suppl.), 1115-1123.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2004). TheRobert Wood Johnson Foundation. (2004, June 2-4). TheSurgeon General's call to action to prevent and decreaseTimeIABC News Summit on Obesity. Retrievedovenvieght and obesity. Retrieved January 3,2005 fromSeptember 20,2004 from h :// .timee.c0m/time/2004/ y/program3.htmlWestman, E. C. & Volek, J. S. (2002). Very-low-carbohydrateSchmidt, C. W. (2003). Obesity: A weighty issue for children.weight-loss diets revisited. Cleveland Clinic Journalof Medicine, 69,849-862.Environmental Health Perspectives, 111(13), A700A707.Yancy, W. S., Olsen, M. K., Guyton, J. R., Bakst, R. P., &Westman, E. C. (2004). A low-carbohydrate, ketogenicStem, L., Iqbal, N., Seshadri, P., Chicano, K. L., Daily, D. A.,McGrory, J., et al. (2004). The effects of low-carbohydratediet versus a low-fat diet to treat obesity andversus conventional weight loss diets in severely obesehyperlipidemia:A randomized, controlled trial. Annalsof lnternal Medic

carbohydrate diet may try one in the next two years. Low-Carbohydrate Diets History Dramatically restricting carbohydrate consumption appeared to be a revolutionary way of losing weight when it was first promoted by Dr. Robert Atkins in 1972. It allowed