Transcription

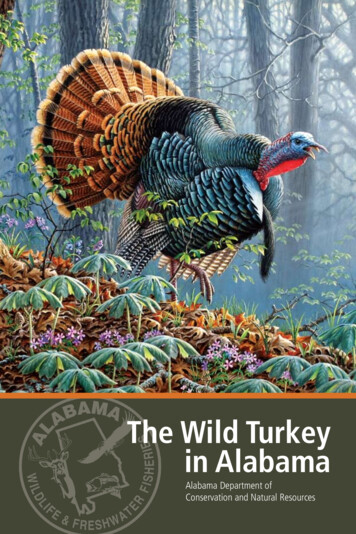

1The Wild Turkeyin AlabamaAlabama Department ofConservation and Natural Resources

Cover “Oak Ridge Monarch”provided courtesy of Larry Zachwww.zachwildlifeart.com

The Wild Turkeyin AlabamabySteven W. Barnett & Victoria S. BarnettWildlife BiologistsAlabama Department of Conservation and Natural ResourcesDivision of Wildlife and Freshwater FisheriesM. Barnett LawleyM. N. “Corky” PughCommissionerDirectorGary H. MoodyFred R. HardersChief, Wildlife SectionAssistant DirectorSupport for development of this publication was providedby the Wildlife Restoration Program and the Alabama Division ofWildlife and Freshwater Fisheries with funds provided by yourpurchase of hunting licenses and equipment.Additional funding assistance provided by the AlabamaChapter of the National Wild Turkey Federation.outdooralabama.com0009-2008The Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources does not discriminate on the basis of race, color,religion, age, gender, national origin or disability in its hiring or employment practices nor in admission to, or operationof its programs, services or activities. This publication is available in alternative formats upon request.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTSI must first express my sincere appreciation to my wife, Victoria, for coauthoringthis book with me. She graciously volunteered her time and energy to assist mewith this endeavor which greatly expedited the completion of the manuscript.Both authors thankfully acknowledge those individuals who provided extensiveand constructive reviews of this book. We appreciate the support and encouragement expressed by the Alabama Division of Wildlife and Freshwater Fisheries andmanuscript reviews provided by the following Wildlife Section personnel: GaryMoody, Chief; Keith Guyse, Assistant Chief; David Hayden, Assistant Chief; ChrisCook, Wildlife Biologist, for offering an outline of suggested steps to follow thatproved helpful in completing the book; Andrew Nix, Forester, for providing muchof the timber management information; Mark Sasser, Non-Game Coordinator;Ron Eakes, Supervising Wildlife Biologist; Bill Gray, Supervising Wildlife Biologist; Stan Stewart, Wildlife Biologist; and Richard Tharp, Wildlife Biologist. TheInformation and Education Section of the Alabama Department of Conservationand Natural Resources contributed greatly to the development of this publication,especially Kim Nix, Chief, and Billy Pope, Art Director.Other reviewers who provided valuable input and suggestions to improve themanuscript were M.N. “Corky” Pugh, Director, Alabama Division of Wildlifeand Freshwater Fisheries; Dr. James Earl Kennamer, Chief Conservation Officer,National Wild Turkey Federation; Tom Hughes, Director of Research and Outreach, National Wild Turkey Federation; and Rhett Johnson, Co-Director andFounder (retired), Longleaf Alliance, Auburn University School of Forestry andWildlife Sciences.

A special thanks is extended to Dr. Dan Speake, Unit Leader (retired), USGS, Alabama Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit, for not only his review andcritique of the manuscript, but his extensive research on wild turkeys that has contributed to Alabama’s successful wild turkey programs.We appreciate and acknowledge all those who provided photographs. We are especially indebted to Matt Lindler, Photography Director, National Wild TurkeyFederation, for providing many of the photos used in this book. We are grateful torenowned wildlife artist Larry Zach for allowing us to use his painting, “Oak RidgeMonarch” for the cover of this publication. We also appreciate the time and effortthat Dr. M. Kevin Keel, Assistant Research Scientist, Southeastern CooperativeWildlife Disease Study, took in locating and submitting photos used in the text.Our thanks go to Mitchell Marks, Tes Randle Jolly, Billy Pope and Dennis Holt fortheir photo contributions.Acknowledgement credits are cited in the captions of all photos and other graphicsthat the authors used in this book. Photographs not acknowledged were providedby the authors.Lastly, but foremost in my thoughts, I thank my father, Carol F. Barnett, an accomplished woodsman and turkey hunter, for mentoring and instilling in me asa young child, during all those early hunting adventures, the intrinsic value of abeautiful spring sunrise filled with gobbles of the wary wild turkey.Steve Barnett

ABOUT THE AUTHORSBilly PopeSteven W. Barnett received a B.S. in WildlifeManagement from Auburn University in1984. He held research assistant positionsfor Auburn University on wild turkey andquail studies following graduation. Stevenbegan his career with the Alabama Division of Wildlife and Freshwater Fisheries in1986 as an Area Wildlife Biologist in Washington County. In 1999, Steven transferred to Baldwin County in hiscurrent assignment as an Assistant District Supervisor and Area WildlifeBiologist. He serves as the Wild Turkey Project Leader for the AlabamaDivision of Wildlife and Freshwater Fisheries. Steven also serves on theTechnical Committee for the National Wild Turkey Federation.Victoria S. Barnett received a B.S. in Wildlife Resources from West Virginia University in 1983 and a M.Ed. in Science Education from the University of South Alabama in 1990. She served as a research assistant forAuburn University on wild turkey and quail studies, and worked as anaturalist at Historic Blakeley State Park. Victoria has also held variousteaching positions in Mobile and Baldwin Counties and is currently theChildren’s Librarian at the Bay Minette Public Library.Steven and Victoria live in Bay Minette with their daughterElizabeth and son Jake.

The Alabama Division of Wildlife andFreshwater Fisheries dedicates this publication to those individuals who led thecharge of the wild turkey conservationmovement in Alabama to bring this magnificent animal from the brink of extinction tothe levels that we enjoy today. We also dedicatethis book to the memory of James R. Davis, a wildlifebiologist who was on the front line of the early wild turkey investigationsand restoration activities in the state.Jim Davis was born in Montgomeryin 1929. He attended Alabama PolytechnicInstitute from 1947 to 1951, receiving his B.S.in Game Management. He was called to ActiveDuty with the U.S. Army in July 1951 and tookpart in two campaigns during his service withthe Second Infantry Division in Korea. He laterreceived his M.S. in Game Management fromAuburn University in 1955 for his work on thefood habits of the bobcat in Alabama. Jim beganhis career with the Alabama Division of Wildlifeand Freshwater Fisheries (then Game and FishDivision) in 1955. He was a District Supervisorin southwest Alabama and played a vital rolein the early days of wild turkey investigationsJim Davis with an adult gobbler heharvested at the Scotch Wildlifeand restoration efforts. Jim later served as ChiefManagement Area in Clarkeof the Wildlife Section from 1984 until hisCounty, Alabama. Photo courtesyretirement in 1989. During his 34-year career,of Jimmy Brown.Jim authored publications on white-tailed deer,wild turkeys, gray squirrels, and mourning doves.He oversaw the publication of special reports onwoodchuck, ruffed grouse, and the golden eagle. Jim was the first president of the AlabamaChapter of The Wildlife Society in 1978-79 and was instrumental in getting the chapterstarted. He had a keen interest in wild turkey management and was passionate abouthunting turkeys in not only Alabama but across the United States and in Mexico. Jim servedon the National Wild Turkey Federation’s first Technical Committee created in 1975 madeup of state agency wildlife biologists. Following his retirement, Jim remained active on hisCovington County property until his death in May 2005.

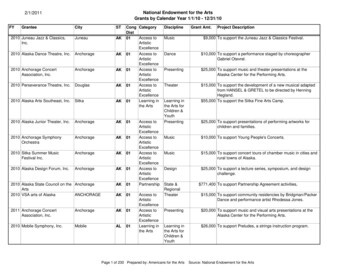

Table of Contents12 PREFACE14 TAXONOMY16 CHAPTER ONEPHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS17 ADULT CHARACTERISTICS17 PLUMAGE18 WEIGHTS18 BEARDS19 SPURS20 SENSES21 MOBILITYNWTF21 POULT AND JUVENILE CHARACTERISTICS21 PLUMAGE21 WEIGHTS21 MOBILITY22 CHAPTER TWOBEHAVIOR23 VOCALIZATION AND COMMUNICATIONNWTF24 BREEDING SEASON24 COURTSHIP25 NESTING25 NEST SITE SELECTION26 LAYING AND INCUBATION

26 BROODS28 CHAPTER THREEFOOD HABITS AND NUTRITIONMitchell Marks29 POULTS30 JUVENILES31 ADULTS32 NUTRITIONAL NEEDS33 MANAGEMENT IMPLICATIONSAND SUPPLEMENTAL FEEDINGSoutheastern CooperativeWildlife Disease Study36 CHAPTER FOURDISEASES, PARASITES, AND TOXINS37 INFECTIOUS DISEASES39 PARASITES41 TOXINSForest Images42 CHAPTER FIVEPREDATORS43 PREDATOR IMPACTS ON TURKEYS45 PREDATOR CONTROL46 CHAPTER SIXPOPULATION DYNAMICSNWTF48484848REPRODUCTIONNESTINGHEN SUCCESSCLUTCH SIZE AND HATCHING SUCCESSTABLE OF CONTENTS27 FALL AND WINTER

49MORTALITY49 NATURAL MORTALITY49 HARVEST MORTALITY50 CHAPTER SEVENPOPULATION MANAGEMENT51 RESTORATION HISTORY IN ALABAMA51EARLY EFFORTS51 TRAPPING METHODS53 TRANSPORTING AND RELEASE54 STOCKING NUMBERS54 WILD TURKEY SOURCES AND RELEASESTES RANDLE JOLLY54 RESTOCKING RECORDS STATUS56 ALABAMA POTENTIAL RANGE REQUIREMENTS56 CURRENT POPULATION58HARVEST STATISTICS58 HUNTER MAIL SURVEYNWTF59 WILDLIFE MANAGEMENT AREAS60 HUNTER EFFORT61 SEASONS61 REGULAR SEASONS61 SPECIALTY HUNTS62 HUNTING QUALITY62 PRIVATE LANDS63 PUBLIC LANDS64 CHAPTER EIGHTRESEARCH AND SURVEYSNWTF

69 HABITAT REQUIREMENTS70 NESTING HABITAT71 BROOD-REARING HABITAT72 FALL AND WINTER HABITATNWTF73 HABITAT ENHANCEMENT TECHNIQUES73 WILDLIFE OPENINGS77 BROOD HABITAT77 PRESCRIBED FIRE78 SELECTIVE HERBICIDES79 DISKING AND MOWING80TIMBER MANAGEMENT85TREE PLANTING85 PROTECTION86 CHAPTER TENWILD TURKEY MANAGEMENTGUIDELINES FOR LANDOWNERS87 HABITAT AND HARVEST STRATEGY87 LANDOWNER ASSISTANCE CONTACTS88 HARVEST STRUCTURE89 DATA COLLECTION89 HARVEST DATA94 SUMMARY96 LITERATURE CITED100 APPENDICESTABLE OF CONTENTS68 CHAPTER NINEHABITAT MANAGEMENT

12PREFACEThe Eastern wild turkey is a commonly encountered species throughout Alabama. Once believed to thrive only in large, unbroken expanses of forestlands,the wild turkey has proven to be quite adaptable to a wide range of landscapesand habitat management applications. Like many other wildlife species, turkeysdo best in diverse habitat settings. The success of population expansion by turkeysis directly related to the amount and quality of brood rearing habitat. However,knowledgeable wildlife managers apply a holistic approach by understanding thatall components of the habitat must be managed year round across the landscapewithout focusing on any single feature. Wild turkey numbers have soared fromnear extinction levels in the early 1900s to an estimated 500,000 in Alabama in2007. This phenomenal increase is a result of proper management embedded inrestoration, protection, research, and partnerships with landowners and conservation organizations.With an increased number of gobbles echoing in the springtime woodlands andmore fall flocks scratching in the leaf litter for acorns, the number of hunters pursuing this wary bird has increased. Larger harvest levels can be linked to morehunters afield as well as more birds available to harvest. The earliest Alabama mailsurvey records from the 1963-64 season reflected that close to 37,000 huntersspent about 148,000 man-days hunting in the combined fall and spring seasonsand harvested about 16,000 gobblers. In contrast, the 2006-07 combined fall andspring seasons indicated about 58,000 hunters who spent close to 495,000 mandays harvesting about 72,000 gobblers.The increase in turkey numbers and turkey hunters has greatly affected the economy in Alabama. Recent nationwide studies of the economic impact of springturkey hunting revealed that about 2 billion is spent annually by nearly 3 million hunters on licenses, permits, firearms, hunting gear, and travel-related expenses. These expenditures average about 800 spent by each spring turkey hunterper season. To put this in Alabama-specific terms, the studies indicate about 45million is spent annually for spring turkey hunting based on the 56,800 reportedspring turkey hunters in 2007.

13However important the economic value may be, the value not measured by dollars is what defines having the wild turkey as part of the landscape. The intrinsicworth of the wild turkey and other wildlife is linked to a much larger conservation picture. Maintaining healthy populations of wildlife such as turkeys and theirhabitats will help ensure an overall healthy ecosystem. Aldo Leopold (1966) statedin A Sand County Almanac that, “ a system of conservation based solely on economic self-interest is hopelessly lopsided. It tends to ignore, and thus eventually toeliminate, many elements in the land community that lack commercial value, butare essential to its healthy functioning”.In order to maintain and enhance wild turkey populations in Alabama today andin the future, it will be up to landowners and land managers to follow the “landethic” that Leopold spoke of and to apply it across the landscape through habitat conservation and management. Alabama’s current turkey population is a testament to the fact that many landowners continue to follow a responsible andforward-thinking land ethic. Wild turkey enthusiasts throughout the state enjoynumerous gobbles reverberating in the spring from the Appalachian Mountains tothe Mobile-Tensaw Delta as a result of management efforts. These current experiences may offer a glimpse of the past. When William Bartram trekked through thesoutheast in the mid 1700s, he reported in his Travels (Harper 1998), in referenceto wild turkey gobbling in the spring, that, “The high forests ring with the noise of these social centinels (sentinels), the watch-word being caught and repeated,from one to another, for hundreds of miles around; insomuch that the wholecountry, is for an hour or more, in an universal shout.”This book is provided as a tool to assist landowners and land managers in Alabamawith the application of habitat enhancement strategies for wild turkey management. In addition, it can be used to guide harvest structures and how to collectharvest data. Hunters as well as individuals with a general interest in wild turkeyswill also find this publication to be a valuable source of information.

14TAXONOMYThe Eastern wild turkey, Meleagris gallopavo silvestris, found in Alabama is oneof the five subspecies of wild turkey in the family Meleagrididae that occur inNorth America. The eastern wild turkey inhabits the eastern half of the UnitedStates. It was named by L.J.P. Vieillot in 1817 using the subspecies word silvestris,which means “forest” turkey. Other subspecies of Meleagris include M. g. osceola,the Florida turkey located in the southern half of Florida; the Merriam’s wild turkey M. g. merriami of the mountain regions of the western United States; M. g.intermedia, the Rio Grande wild turkey, which is found in the south-central plainstates; and the fifth recognized subspecies of the wild turkey, the Gould’s M. g.mexicana, which is located in northwestern Mexico and parts of southern Arizonaand New Mexico. The ocellated turkey M. ocellata is a different species that occursin the Yucatan Peninsula of eastern Mexico as well as adjacent countries of Guatemala and Belize.There were over7 million wild turkeysreported in North Americain 2007. Map datacourtesy of the NationalWild Turkey Federation.n EASTERN WILD TURKEYn FLORIDA WILD TURKEYn RIO GRAND WILD TURKEYn MERRIAM’S WILD TURKEYn GOULD’S WILD TURKEYn HYBRID WILD TURKEYn OCELLATED WILD TURKEY

15Eastern Wild TurkeyMeleagris gallopavo silvestrisNWTF

Chapter OnePhysical Characteristics

PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICSWild turkeys are classified as gallinaceous birds along with grouse, quail, andpheasants. This group of birds spends the majority of daily activities, such asforaging, mating, and nesting, on the ground. They all have strong feet andlegs for running and scratching as well as rounded wings that enable shortbursts of flight. Like other Galliformes, turkeys are sexually dimorphic meaning that the male is larger and more colorful than the female as a function ofcourtship and display. The female’s drab coloration serves as camouflage toelude predation, which facilitates successful nesting.ADULT CHARACTERISTICSPLUMAGEThe adult turkey is covered withbetween 5,000 and 6,000 feathers inpatterns called feather tracts (pterylae) (Marsden and Martin 1945).Feathers range in size from hair-likefiloplumes to large stiff, quill-likewing feathers (remiges) and tailfeathers (retrices). Besides for flight, feathers of various shapes function as body covering, insulation,and waterproofing. Feathers also facilitate tactilesensation for sensory organ protection, and function as ornamentation for display and recognition.Many feathers exhibit iridescence, most prominently in gobblers, with varying colors of red,green, copper, bronze and gold. The brightness andangle of light as well as body movements determinethe level of feather iridescence. Generally, body feathers of gobblers areblack tipped, giving the malean overall black appearance at a distance. Thehen has a duller appearance due to brown tipped bodyfeathers. Contour breast feathers aresquare tipped in males and are morerounded in females.The head and neck area of gobblers isbasically naked with very few feathersThe breast feathers ofgobblers (Top) are blackedtipped. Hen breast feathers(Below) are buffed-tipped.NWTFNWTFA gobbler’shead and neck isbasically featherlessand characterizedby red, white, andblue coloration.NWTF

18 P h y s i ca l C haract e r i st i cson bare skin protuberances calledcaruncles. These bare skin areasof the gobbler’s head and neck areone of the most distinguishingcharacteristics of the sexes. Maleshave red, white, and blue colorationsthat are most evident in the breeding season.Unlike the gobbler, the hen is feathered in the headand neck region. The female exhibits a smaller, dullblue colored head and less prominent caruncles ascompared to an adult male.The head and neck areaof a hen is feathered tosome extent with a mostlyblue coloration.Uncharacteristic colorations have been reported inwild turkeys. There are four abnormal color phases:smokey gray phase, melanistic (black) phase,erythritic (red) phase, and the very rare albinotic(white) phase. These unusual plumage colorationsare reported infrequently in Alabama.WEIGHTSAn adult Eastern wild turkey gobbler will average between 16 to 20 pounds,while the average adult hen will weigh between 8 to 10 pounds. Based on hunterharvest records kept by the National Wild Turkey Federation (NWTF), a gobblerweighing close to 26 pounds was documented in Lauderdale County in 2006as being the heaviest in Alabama. The heaviest Eastern wild turkey reportedweighed over 35 pounds and was harvested in Iowa in 2001.BEARDSThe beard, primarily found onmales, is a brush-like cluster ofkeratinous fibers, similar to hair,that hang from the midline of theupper breast (Lucas and Stettenheim 1972). It is often considereda modified feather; however, the beard does not molt asa feather does. Another suggestion is that the beard is aspecialized part of skin that grows throughout the life of aturkey. Filaments of the beard originate from a raised ovalof skin known as a papilla (Lucas and Stettenheim 1972).Multiple beards sometimes develop from multiple papillaeresulting in several distinct beards on a turkey.Most gobblers have beards visible beyond the breast feathers at 6 to 7 months of age. The beard continues to grow ata rate of about 3 to 5 inches per year. However, the tip ofBeard lengths increase asa gobbler ages but normalwear and breakages makesaging difficult beyond ajuvenile bird.

P h y s i ca l C haract e r i st i cs 19the beard will begin to wear off at 2 years of age due to ground friction duringforaging and other daily activities. Gobblers with a longer skeletal structure,resulting in greater height, tend to have longer beards because of groundclearance. Beard thickness depends on the number of bristles stemming fromthe papilla. The normal color of an adult turkey beard is black throughout itslength. Juvenile male beards often have reddish or blonde tips. This color disappears in older gobblers as the bristles grow in length and wear off at the tip.Some beards of adult males will be partially or completely broken off horizontally, which is usually associated with a lack of the black pigment melaninresulting in brittle beard filaments.Even though the papilla from which the beard grows is present on hens,female turkeys do not normally have beards. Research has shown that henswith beards may range from 1 to 29 percent of females from different populations (Lewis 1967, Williams and Austin 1988).NWTF wild turkey harvest records indicate that the longest typical beard on agobbler in Alabama was over 17 inches in length and was taken in TuscaloosaCounty in 2001. Based on these records, the longest typical beard for an Eastern wild turkey was reported by a hunter in Texas in 2007 at over 22 inches.SPURSSpurs are located on the lower scaled sectionsof gobbler legs. There is usually one spur on eachleg. Spurs are used for fighting associated primarilywith the spring breeding season in order to establishdominance. The spur of an adult male has a bonycore and is covered by keratin. As a gobbler agesthe shape of the spur will gradually change from round and blunt tocurved and sharp. The length of spurs can be used to determine age tosome extent. Generally, juvenile males have spurs less than ½ inches,a 2-year-old male will have spurs up to ⅞ inches, and 3-year-oldplus males may have spurs 1 inch and longer.Spur length is a more reliable aging index than beard length but growth rates arenot constant and vary among gobblers based on genetics, habitats, and other factors.

20 P h y s i ca l C haract e r i st i csJohnny PonderMost spurs are black but canvary in color from black andreddish, pink, off-white, or acombination of these colors.Rarely, a hen will be reportedwith spurs or a gobbler withmultiple spurs. Some adultgobblers have been observedwithout spurs.According to NWTF wildturkey harvest records, theSome gobblers are reported with multiple spurs.longest typical spurs reportedin Alabama were on birds taken in Choctaw (1992) and Perry (1978) counties.Each of these gobblers had spurs that were 1⁷ ₈ inches in length. Based on NWTFharvest records, the longest typical spurs reported for the Eastern wild turkeywere 2¼ inches long from Iowa (2001) and Kentucky (1999) gobblers.SENSESTurkey hunters can attest to the fact that wild turkeyspossess excellent vision. Turkeys have the ability todetect the slightest movement and many turkey huntershave learned this the hard way. The rate of assimilationof detail in the field of vision of the wild turkey is veryrapid (Lewis 1967). With eyes on the side of its head, aturkey has predominately monocular, periscopic vision.A turkey needs only to turn its head and view an objectfrom different angles to determine distances, whichallows for a 360-degree field of vision. Night vision ispoor and turkeys are reluctant to leave the roost at night.Nocturnal birds such as owls have a preponderance ofrods in the retina associated with night vision. Turkeysare diurnal (daytime) birds and have mostly cones inthe retina for daytime vision (Dukes 1947). Turkeys doperceive colors, the extent of which is unknown.The wild turkey has an acute sense of hearing. Field observations indicate that turkeys can hear lower frequencies and more distant sounds than humans can.Taste and smell are poorly developed in turkeys as compared to humans. Turkeys have fewer taste buds but candifferentiate simple tastes such as sweet and bitter. Theolfactory lobes in the brain of a turkey are small, whichaccounts for a poor sense of smell.

P h y s i ca l C haract e r i st i cs 21MOBILITYWild turkeys have powerful legs that enable them to run well. Infact, heavy adult gobblers prefer to run rather than fly to eludedanger. Ground speeds in excess of 12 mph allow the turkey tospring into the air to take fight in an instant (Mosby and Handley1943). Flying speeds of up to 55 mph have been reported (Mosbyand Handley 1943). Continuous wing beats of turkeys rarely exceed 200 yards in flight distance, but gliding associated with wingbeats may permit turkeys to fly up to a mile with little difficulty.POULT AND JUVENILE CHARACTERISTICSPLUMAGEAt hatch, a turkey poult is covered with yellowish brown natal down and hasseven small primary flight feathers (Williams 1981). At about three weeks of agethe flight feathers are well developed. The first body feathers are brownish andthe poult may appear similar to a young grouse. A young turkey will go throughfour plumages and three molts (feather replacements) by the first winter. At threemonths of age the young turkey will first attain adult colored plumage.WEIGHTSA wild turkey poult weighs less than 2 ounces at hatch but the growth rate posthatch is rapid. A young turkey will gain over 1 pound per month during the firstthree months of life. After three months, the juvenile male will weigh about 3pounds, slightly more than the female juvenile (Mosby and Handley 1943). Thegrowth rate is accelerated between three and seven months with weight gainsof about 1 pound every two weeks. At around five to six months of age, younggobblers will weigh between 9 and 11 pounds. A juvenile hen will weigh about 8pounds at seven months of age.MOBILITYNWTFWild turkeys are flightless uponhatching, which leaves them vulnerable to predation and other mortality factors. However, due to rapid growthin flight feathers (wings), the developing poult can fly up to low branchesat eight to 12 days of age. Mobilityin terms of ground speed and flightimproves as a juvenile grows, whichaids in evading predators and promotessurvival into the first fall season.Newly hatched poultssuch as this are veryvulnerable to mortalityfactors for the first fewweeks after hatching.

Chapter TwoBehavior

BEHAVIORVOCALIZATION AND COMMUNICATIONResearch has shown that a turkey’s vocabulary consists of 28 distinctcalls (Williams 1984). The obvious call that is specific to the maleturkey is the gobble. Both sexes canemit common calls such as yelps,clucks and putts. Gobbles aretypically used in the springbreeding season by malesto attract females, butgobblers also gobble to assertdominance in areas of other competing malesduring the mating season. Males also gobble asa response stimulus to other calls from owls,crows, woodpeckers, coyotes etc. or loud noisessuch as trains, thunder and gunshots. Calls suchas yelps, clucks and putts are used throughoutthe year. In the spring mating season, receptive hens will primarily use yelps and clucks inresponse to gobbles heard. The putt or alarm puttis used to communicate a threat and results in analert posture with head up or an immediate flushthrough running away or taking fight.Hunters use a wide assortment ofcalling devices such as this box callto imitate hen calls produced in thebreeding season and lure in gobblers.NWTFNWTFMost turkey hunters carry a repertoire of calling devices to imitate the vocalizations of wild turkeys suchas box calls, diaphragmmouth calls, glass calls, slatecalls, turkey wingbone calls,gobble tubes and several othertypes. Many hunters have discovereda biologically sound reason for carrying awide array of calls. A particular gobbler thatmay not respond to one type hen call mayrespond to another call due to the differencein the “voice” of the caller.

24 B e hav i o rBREEDING SEASONBreeding behavior, such as gobblingand strutting, is triggered by increasedperiods of daylight in late winter. Theseactivities are also stimulated by warming trends. This pre-courtship activitywill occur before spring dispersal whilegobblers are flocked together. Hierarchyor pecking order within flocks is formedby fighting to establish dominance, hencethe term “boss” gobbler. Winter flockswill establish these complex social ordersboth within and between flocks of thesame sex.NWTFCOURTSHIPGobblers establish dominance in pre-courtshiprituals to establish pecking ordersdennis holtAs daylight periods increase and warming trends continue, gobbling and strutting behavior intensifies into the spring mating season. There are usually twopeaks of gobbling associated with the mating season. The first peak is at the onsetof breeding when gobblers are searching for hens, while the second peak occurslater when most hens are incubating (Bailey and Rinell 1967). A two-year studyof gobbling activity in Alabama at the Fred T. Stimpson Sanctuary in Clarke County measured peak periods of the number ofgobblers heard as well as the number of gobbles emitted. Thesurvey was conducted for two hours starting 30 minutesbefore sunrise each morning. The first averagepeak of gobblers heard occurred about March19 (three gobblers), with the second averageprimary peak observed around April 6 (eightgobblers). The highest number of gobblesemitted was on April 5 (46 gobbles). InAlabama, the gobbling (breeding) seasonbegins in March and lasts well into May(Davis 1976).Strutting is part of courtshipdisplay to attract hens inthe mating season.Gobbling activity is highly variable. Thenumber of different males gobbling aswell as the number of gobbles emitted may vary greatly from day to day.Even during peak periods of gobblingon days of optimum weather conditions (mild, calm and clear), some turkeysremain silent. In one Alabama study, littlegobbling was heard on rainy and windymornings (Davis 1971). The only fairly

b e hav i o r 25consistent observation regarding gobbling reflected in the study is that peak gobbling usually occurs between 30 minutes before and 30 minutes after sunrise.The primary function of gobbling is to attract hens for mating (Williams 1984).Hens respond to gobbling by yelping

Biologist. He serves as the Wild Turkey Project Leader for the Alabama Division of Wildlife and Freshwater Fisheries. Steven also serves on the Technical Committee for the National Wild Turkey Federation. Victoria S. Barnett received a B.S. in Wildlife Resources from West Vir-ginia Universi

![INDEX [randycherry ]](/img/21/x-20-20tv-20fakebook-20-20hal-20leonard.jpg)