Transcription

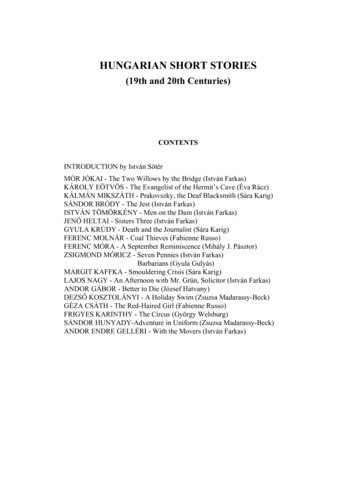

HUNGARIAN SHORT STORIES(19th and 20th Centuries)CONTENTSINTRODUCTION by István SőtérMÓR JÓKAI - The Two Willows by the Bridge (István Farkas)KÁROLY EÖTVÖS - The Evangelist of the Hermit’s Cave (Éva Rácz)KÁLMÁN MIKSZÁTH - Prakovszky, the Deaf Blacksmith (Sára Karig)SÁNDOR BRÓDY - The Jest (István Farkas)ISTVÁN TÖMÖRKÉNY - Men on the Dam (István Farkas)JENŐ HELTAI - Sisters Three (István Farkas)GYULA KRÚDY - Death and the Journalist (Sára Karig)FERENC MOLNÁR - Coal Thieves (Fabienne Russo)FERENC MÓRA - A September Reminiscence (Mihály J. Pásztor)ZSIGMOND MÓRICZ - Seven Pennies (István Farkas)Barbarians (Gyula Gulyás)MARGIT KAFFKA - Smouldering Crisis (Sára Karig)LAJOS NAGY - An Afternoon with Mr. Grün, Solicitor (István Farkas)ANDOR GÁBOR - Better to Die (József Hatvany)DEZSŐ KOSZTOLÁNYI - A Holiday Swim (Zsuzsa Madarassy-Beck)GÉZA CSÁTH - The Red-Haired Girl (Fabienne Russo)FRIGYES KARINTHY - The Circus (György Welsburg)SÁNDOR HUNYADY-Adventure in Uniform (Zsuzsa Madarassy-Beck)ANDOR ENDRE GELLÉRI - With the Movers (István Farkas)

INTRODUCTIONHungarian literature, one of the least known literatures in Europe, has produced works ofinternational literary rank mainly in the realm of poetry. The traditions of Hungarian versedate back to the sixteenth century, to the first great Hungarian lyricist, Bálint Balassi. Hevoiced not only the exuberance of the Hungarian Renaissance, but his boisterousness andsentimentality, his choice of themes dealing with the warrior’s life, with love and religiousfervour, made him a model for subsequent generations of Hungarian poets. From thebeginning of the nineteenth century to the present day, Hungarian literature has been atriumphal march of lyric poetry - each generation saw the emergence of great lyricists, whohave, however, remained almost completely unknown to people abroad and to internationalliterary opinion. The reason? Perhaps that the language of Hungarian poetry has always beenrefreshed from folklore and the archaic sources of Hungarian literature, so that the faithfulreproduction of the hues of its idiom would have required extraordinary gifts and poetic poweron the part of the translators. But the isolation, the unfamiliarity of Hungarian poetry and ofHungarian literature generally, may also be explained by the fact that in the last century, thechief concern of our authors was with the establishment of a national character. This concernoverruled another - that of speaking to Europe, to mankind at large, and with it therequirement of contents that would transcend national limitations.While Hungarian poetry was able, by the end of the eighteenth century, to boast of severalgreat poets, narrative prose remained in its naive, archaic state. The novel, this most bourgeoisproduct of European bourgeois development, was even as late as the first half of thenineteenth century only in an incipient stage in this country. Yet there had been quite a fewspontaneous and characteristic manifestations of narrative art in earlier Hungarian prose. Theparables of mediaeval codices, some of the dramatic passages in seventeenth-centurymemoirs, portions of the correspondence of Transylvanian princes and aristocrats, and, ofcourse, the treasure trove of Hungarian folk tales - all these were important precursors of laterHungarian narrative writing.In the first half of the nineteenth century it was the imitation of Eugène Sue and Walter Scottthat set off the development of the Hungarian novel. The “mysteries” of the former weresomewhat alien to the environment of the provincial Hungarian towns into which they weretransplanted - the historical atmosphere of the latter was far better suited to the subjects andcharacters of Hungarian history. It was after such preliminaries that the Hungarian novel wasborn in the works of Mór (Maurus) Jókai, at the middle of the last century. Jókai establishedthe national form of the Hungarian novel - in his picturesque and romantic manner heportrayed the personalities of the period preceding the revolution of 1848 - of the then recentpast - the heroes of the Hungarian independence movements, the morals, customs and scenesof the vanishing feudal-patriarchal Hungary. The charm of Jókai’s works is due to thenostalgic colouring of the recent past and his emotional, melancholic farewell to an old andfamiliar world. This nostalgia and emotion may also be felt in his short stories. The writers ofthe second half of the century - particularly Mikszáth, who in many respects followed Jókaiand may, next to him, be regarded as the most significant author of the period - sang the swansong of the developing bourgeois Hungary to the old, intimate, patriarchal Hungary. In theshort stories and novels of Jókai and Mikszáth the old world is clad in fairy hues; amid theconditions of capitalist Hungary, the epoch whose termination was marked, by 1848 suddenlycame to seem humane and pleasant, heroic and interesting, though it had in fact been tainted2

by Hapsburg tyranny, feudal conditions and semi-colonial subservience to the Austrianempire. In this manner, Jókai and Mikszáth established a lyrical approach to the recent past.They saw heroes and eccentrics in the Hungary of yore, and both types equally require thedescriptive art of romanticism and of realism to portray them. With Jókai and Mikszáth theHungarian towns and country manors became populated with strange and unique charactersand personalities. The art of these writers harbours a peculiar confession - that the second halfof the century looked with emotion and pain upon the hopes and aims that had preceded 1848.The defeat of the revolution and of the struggle for freedom had thwarted the fulfilment ofthese aims and the hopes remained unrequited. Jókai and Mikszáth voiced the feelings of the‘‘better half” of the nation - capitalist Hungary looked back on the Hungary of the pre-1848period, as upon its own better part. Or, as a mature and disillusioned man, upon the happy,magnanimous, youthful period of great expectations, bold ventures and selfless heroism.It was Jókai and Mikszáth who gave birth to modern Hungarian short-story writing. Theseshort stories were a development of the anecdote, itself the favoured literary form of the old,patriarchal Hungary. These full-flavoured anecdotal short stories, built up round a point, are inmany ways different from Maupassant’s type of short story. The characters of these shortstories are heroes or eccentrics. The anecdote is suitable for the portrayal of both types. Itskindly, humorous savour deprives heroism of its poignancy, and eccentricity of the painfulfeeling of backwardness. The faithful heir, tender and cultivator of the anecdotal art of Jókaiand Mikszáth was Károly Eötvös.End-of-the-century Hungary awoke from its romanticism. In our country this romanticism hada longer after-life than anywhere else in the world. The cult of the recent past entertained bythe period of capitalism, could only be maintained amid the forms of romanticism. But theyoung generation of writers at the end of the century had no reminiscences of this pre-1848fairyland. Their experiences were simpler and more bitter. A truly urban Hungary had comeinto being, which saw even the village differently than the patriarchal mid-century generation.This period turned its attention to the unsolved, unsettled social problems of its day - and thebreath of a new revolution may be felt in the passion with which the young generation drewattention to the destitution of the peasantry, the defencelessness of simple people and thedepravity of the gentry. One of the leading figures of this new literature - a special kind oflittérature engagée that was permeated with a sense of responsibility - was Sándor Bródy.And in his immediate vicinity, István Tömörkény provides an example of the philanthropic,sympathetic view of the people entertained by the urban intelligentsia. Tömörkény made averitable discovery of the peasant world which the heirs of romanticism had so far onlypresented on the scenes of bucolic plays and sentimental short stories, in an idealized, syrupysetting. His short stories are sometimes rendered cumbersome by their ethnographicdescriptions - inventories of customs, implements and the peculiarities of various trades.Zsigmond Móricz, with his rich knowledge of the peasantry, thought Tömörkény’s shortstories were “ethnographic museums.” Yet there was need for this “inventory” to be made,because the world which Tömörkény described was as unknown to the educated classes as thelife of an African tribe. More or less contemporaneously with the poor of the farmsteads onthe pusztas, this period also discovered the urban poor, the proletarians. Ferenc Molnár wasthe first, before he undertook his more celebrated but also more superficial ventures instagecraft, to take note of the urban poor and to discover the bitter-sweet poetry of their life.The generation of short-story writers who emerged at the turn of the century, played only theoverture to the great poetic revolution that developed in this country between 1905 and 1919.This was intrinsically a revolutionary period, throughout Europe. The unallayed, defeatedHungarian revolution of 1848-1849 came to life again in the bourgeois revolution of 1918 and3

the proletarian revolution of 1919, undertaking to complete the work that had been leftunfinished in 1849. As in Petőfi’s age, literature at the beginning of the century again becameone of the sources of inspiration for this revolutionary fervour. In the lyrical field, the soaringpoetry of Endre Ady was a portent of the great storm to come. Ady’s companion in prose wasZsigmond Móricz. The revolutionary forces maturing in the peasantry were so strikinglyvoiced in the work of Móricz as though his were the words of a belated participant in theHungarian peasant revolution of the sixteenth century. But Móricz was a belated author inother respects too. It was through his artistic portrayal of reality that Hungarian prose made upfor the omissions of the long-lived post-romanticism of the nineteenth century. This postromanticism had prevented Hungarian novels from presenting a picture of society that was ofsimilar value, or a portrayal of the characteristic types of the period that was of similarrichness to that achieved by European novels from Balzac to Tolstoy. Perhaps it was thisbelatedness that made the medium of Móricz’ work so crowded and dense - perhaps it wasthis that lent his art so synthetic a character. For the synthesis of Móricz includes the conciseand sombre tradition of the Hungarian folk ballads - the “Barbárok” (Barbarians) and “Hétkrajcár” (Seven Pennies) themselves preserve something of this tradition - the linguisticsplendour of the seventeenth-century memorials, and also the procedures of the modern,analytical character-study novel. Móricz’s life work reflected the profound crisis of Hungariansociety after the defeat of the 1919 revolution, as it did the ruin of the peasantry, the decay ofcountry squiredom and the slow, threatening disintegration of the Hungarian bourgeoisie. Forthis very reason, Móricz established a grandiose, pan-national art of novel writing, and withhim the Hungarian novel attained the heights which in poetry had already been achieved in theprevious century.The short stories of Móricz are alternately concerned with idyllic and tragic events. The idylland tragedy are, of course, the two extreme characteristic forms of the feelings entertained inthe period about 1919. By the time of the First World War, Hungarian literature - andnaturally the short story too - were in a highly differentiated condition. The requirement forromanticism, for poesy, again surged to the fore and after the naturalism of the fin de sièclegeneration, by way of a reaction, the new art that used the tools of impressionism alsoappeared in Hungarian short-story writing. The requirement for idyllic writing became butdeeper, under a firmament of social tragedies. The humour and charm of Jenő Heltai is asmuch a satisfaction of the requirement for the idyllic, as is the fairy world of Gyula Krúdy.The nostalgic feelings of Jókai and Mikszáth appear with renewed intensity, in highlydecorative and stylized forms with Krúdy. It is with him that the poetry of the “recent past”gained complete fulfilment - the old Hungary whose figures he presents, is transformed into afairyland of imagination and romanticism. It is obvious that Krúdy is a fugitive from his ownperiod, and this escape into the land of dreams parallels to some extent all that world literaturealso attempted to do in the 1920’s.The national form of the Hungarian novel may be regarded as having been evolved by the firstdecades of the twentieth century. The novels of Móricz, Margit Kaffka and Mihály Babitsmark the conclusion of this process. And nevertheless it seems as though the lyricalinclinations of Hungarian literature were manifested in the fact that the ideal of the perfectform was found in the genre of the short story, instead of large-scale compositions. Thetreasury of Hungarian short stories contains more masterpieces than that of the Hungariannovel. Margit Kaffka, who in her novel “Színek és évek” (Sights and Seasons) sang the swansong of the Hungarian country squires, in her short stories also depicts the crisis of the formerleading class in Hungary. In the 1920’s Hungarian literature became increasingly gloomy. Thefirst signs of this gloom are apparent in the short stories of Andor Gábor. Under the firmament4

of the counter-revolutionary period, escape was offered either by dreams such as Krúdy’s, orby a yearning for the purity and humaneness of the peasants’ world, like that expressed byFerenc Móra. Several of the latter’s contemporaries, in fact, exaggerated the idealization ofthe archaic peasant life and created a peasant myth. Móra, however, remained immune to thiskind of peasant romanticism and contrasted his own age, that of the inter-war years, the age ofthe new barbarism, with the pure humanism of the poor people’s world, the memories of hisown childhood.The period around the First World War may also be regarded as a golden age of Hungarianshort-story writing. Heltai, Krúdy, Kaffka and Móra were not alone in representing thegeneration of authors who replaced the anecdotal style of the previous century with a new artof short-story writing, one that seems both lyrical and philosophical. Short stories played amore important part in the lifework of Dezső Kosztolányi, Géza Csáth and Frigyes Karinthythan in that of any of their contemporaries. Among the writings of Karinthy, permeated withhumour and wisdom, his short stories occupy a singular position - they are his means forexpounding and illustrating one or other of his paradoxes. Karinthy’s embittered playfulnessconceals the moralist’s lack of illusions - for the post-war generation, morals signified whatillusion used to mean for their predecessors. In the first period of Kosztolányi, Csáth andKarinthy the paradox, improvisation and playfulness were dominant. Their strange stories aretoo speculative in character, the idea is too obvious in them. Kosztolányi was led to arecognition of the startling dramas of the human soul by Freudism, thus to achieve the newlydefined morality which was manifested in an emotive, sympathetic love and compassion forerring man. Kosztolányi and his companions - including Géza Csáth - undertook to portray thetragedies of everyday life. The excentrics and heroes of the short stories of the last century, thebarbaric peasants of Móricz’ stories, were in the inter-war period replaced by namelessordinary folk, the humble victims of modern civilization, the undistinguished pariahs of thecities. The majority of Kosztolányi’s stories are about these moving and senseless lives.Bewilderment at the tragedy and senselessness of life was an attitude characteristic of mostshort-story writers between the two wars. The most prominent representative of these wiseand disillusioned authors was Sándor Hunyady. In an age that brought the disruption of formsinto fashion he adhered to strict, classically simple form. Hunyady did not believe in ideals ordevote himself to any particular faith. The way he stands outside, his impersonal observer’svigilance nevertheless express the same moral attitude as that of Kosztolányi or Karinthy. TheHungarian literature of the inter-war years may well be called a literature of diseased times.The moral approach of the period could be most faithfully expressed by the view that thewriter’s main task is to report to his fellow-men on his own forebodings of danger.The works of the two most significant short-story writers of the period, Andor Endre Gellériand Lajos Nagy, are in fact suffused with reports of similar purport. Both expressed the samedisquiet, the same feeling of danger - yet how different their methods were. Gelléri recordedthe realities of the first part of the thirties - the years of the great economic slump. In his shortstories we may discover the specific conception of life entertained at the time - the bittermixture of hopelessness and the urge to live, of pain and joy that then filled the hearts ofdecent men. Gelléri’s short stories are poetic confessions about a remote age, and beyond theapparent playfulness of these confessions, lies the latent threat of tragedy.The unrequited demands of Hungarian history emerged with renewed urgency. Theseunsolved problems had been left as a heritage to the 1930’s by the defeated revolutions of1848 and 1919. In the period preceding the Second World War, Hungarian short storiesheralded the need for change through their terse and precise statement of the gravity of the5

existing situation, the diagnosis and declaration of the phenomena of desintegration and crisis.The great master of this diagnostic, terse and objective art was Lajos Nagy. His writings arevery often gloomy and tenebrous, their satire is embittered and ruthless, their tone acrid andsevere. His lifework showed almost the whole world as hopeless and devoid of prospects. Yetit is actually not misanthropy, but a heightened, humanistic sense of love that is expressed inhis short stories, which by showing the untenable conditions are themselves an argument forsomething better and more humane.The development and fruition of the Hungarian short story has been the work of about acentury and a half. This literary form has acquired an importance similar to that of lyric poetryin Hungarian literature, because it has achieved a fortunate harmony of the inspirationsderived from national and international sources. The anecdotal short stories of postromanticism were superseded at the end of the century, under the influence of the short storiesof Maupassant and Chekhov, by the modern type of short story, which had attained to aposition of hegemony in world literature. Through Móricz the Hungarian short stories that haddeveloped according to the Western form were enlivened by the influence of Hungarianfolklore, and in the 1920’s and 1930’s a path similar to that of Western surrealism wasadopted by Krúdy, while surrealism also exerted a direct influence on Gelléri.The Hungarian short story thus itself underwent the process which was also the mostimportant process of the whole of Hungarian literature - it succeeded in expressing itsspecifically Hungarian message in such forms and by such techniques that have rendered theunique, the national, the particularly Hungarian features comprehensible to a widerinternational reading public.István Sőtér6

MÓR JÓKAI(1825-1904)At one time called “Hungary’s greatest story-teller,” Jókai is still undoubtedly one of her mostpopular writers of fiction. Several of his novels were in his lifetime translated into German,French, English, Russian, Polish and Czech. His patriotic or adventure stories and novels orromances, whether excursions into Hungary’s past history or laid in a contemporary setting,have been favourite reading among several generations.The son of a lawyer, he was intended to join the profession. For some time before the 1848War of Independence he had been one of the coterie which gathered around the poet Sándor(Alexander) Petőfi as its principal moving spirit, and, like his great friend, he too played a part- if a more cautious one - in those momentous events. Following the débacle, he wascompelled to go into hiding, for a régime of ruthless oppression held the country in its sway.As soon as an easing of absolutist terror made this possible, he came out of hiding andreturned to Pest. More historical novels followed. Jókai tried to keep alive his countrymen’sspirit of defiance in the face of their present humiliation by reminding them of the grandeur oftheir national past. Before long, he became tremendously popular. An extremely prolificwriter, Jókai published one novel (sometimes two novels) each year. His historical novels Egy magyar nábob (A Hungarian Nabob), Kárpáthy Zoltán, Erdély aranykora (Midst theWild Carpathians), Törökvilág Magyarországon (The Slaves of the Padishah), A kőszívűember fiai (The Baron’s Sons) - drew on Hungarian history and revived the traditions ofnational courage and independence struggles in the face of the invaders. Novels of manners Az aranyember (Timár’s Two Worlds), Fekete gyémántok (Black Diamonds), etc. - and theUtopian phantasy A jövő század regénye (A Novel of the Coming Century) enhanced hisreputation and increased his popularity. Towards the end of the century, Jókai was theuncrowned prince of Hungarian letters; and, despite his faults, which drew the censure ofcritics (loosely-knit and rambling plots and romantically rough-sketched characters that areeither of angelic goodness or unmitigated scoundrels) his books were eagerly read, and for along time he was the most popular writer in Hungary.The strong appeal of his writings springs no doubt from his excellence as a spinner of yarn. Inhis great talent for plot-hatching he is a close neighbour of the great French romanticists,above all Victor Hugo. His unmatched, poetic fancy conjured up images of distant worlds forthe public of a backward Hungary. His intimate knowledge of detail, of the many littlephenomena of life, gives authenticity to his novels and stories. Romanticism and realism,patriotism and the beauty of the tale are all blended in Jókai’s lifework.7

THE TWO WILLOWS BY THE BRIDGEBetween Felvinc and Nagyenyed, a small mountain brooklet, now spanned by a permanentstone bridge, crosses the road. On either side of the bridge, at the water’s edge, stands anenormous willow: and there is a historical event connected with those two willows. Sevengenerations have seen them grow, and their story has been handed down from father to sonand is remembered to this day as if it had happened in our lifetime.It is now just a hundred and fifty years since the Kuruts-Labants war1 was à la mode, with theKuruts forces setting the rules at Nagyenyed one day, and the Labants fighters taking over thenext. As the former went out at one end of town, the latter came in at the other.The citizens of Nagyenyed could not get it out of their heads that it would have been far, farbetter if these good people had gone to see one another instead of calling on them; but theirvisitors were worldly-wise gentlemen who had some notion of the strategic ruse according towhich one way to beat an enemy is to strip the countryside of its victuals. It was this conceptwhich they put into practice.For while the regular armies of the Prince2 - the cream of the nobility, with their banners,stalwart hussars with wolves’s skins slung over their backs, picked heyducks, and guardsmen,in their red-and-blue uniforms - were fighting pitched battles against the main body of theimperial forces, composed of shining cavalry, mail-clad and crested, of dragoons inembroidered buff-hides, and sharp-shooting musketeers, while all this was going on over therein Hungary3, idle soldiers of fortune roamed the countryside, so very much alike in their looksthat it was impossible to tell the Kuruts from the Labants.They were, for the most part, people who had themselves been ruined by the war and whomdespair, destitution and a thirst for revenge had left no other choice than to take up theirscythes or pickaxes and join either the Kuruts or the Labants camp, according to whosesoldiers had made them destitute.Bands of these vagrants went from town to town, extorting money and looting wherever theymet with submissive inhabitants; indulging in arson, where their anger was roused, and takingto flight as soon as they were scared. They could hardly be called enthusiastic fighters; and thevanquished would as a rule go over to the side of the victors, so that, on Mihály Cserei’s4evidence, there were men who had been on and off the Kuruts side four or five times and asmany times in and out of the Labants camp.Such frequent alterations of quality must have been a serious obstacle in the quest for glory;for if you had made a good name for yourself, you could never be sure that, if your entire hosthappened to go over to the other side one day, the enemy might not see fit to spare them alland to hang you, as the most highly prized object of his revenge.1Anti-Hapsburg war of independence in the 18th century,Kuruts the anti-Hapsburg forces.Labants the pro-Hapsburg forces.2Prince Ferenc II Rákóczi (1676-1735), leader of the anti-Hapsburg war of independence.3Nagyenyed being in Transylvania, then an independent principality.4A historian from Transylvania (1667-1756).8

However, a way out of this predicament was found by assuming false names, by a practicemainly cultivated by the Labants fighters, who strove to find aliases for themselves overwhich those Kuruts nincompoops would twist their tongues - names which more often thannot were corrupted German words that they themselves did not understand.The Kuruts “pashas,” on the other hand, sought to assume Wallachian names.At that time, the most ominous menace that hung over Nagyenyed and the towns of theneighbourhood was represented, on the one hand, by the Kuruts leader Balika, who had takenup his abode in a cavern in Torda Gorge, still referred to as “Balika’s Fort,” and on the other,by the two Labants chiefs who had their quarters in the Mezőség5, and one of whom bore thequeer name of “Traitzigfritzig,” while the other was more romantically called “Borembukk.”Such were their assumed names, such, too, were those who bore them - fellows, now clumsy,now ruthless, half facetious, half sanguinary, of whom many amusing stories - and no fewerhorrible ones - were bruited about, and whose names on the lips of nurses served as bugbearsfor frightening naughty children and in the mouths of roguish Nagyenyed students as epithetsfor jeering at each other.Oh, those students! They were peculiar young fellows, those students of Nagyenyed!As soon as a Calvinist lad had learned the art of making quill-pens out of goose-feathers, hismother would fill up a haversack with scones for him, and his father would buy him a pair oftop-boots and take him to Nagyenyed, where, having put him down in the quadrangle of thecollege, having boxed his ears and given him his blessings, he would leave the boy to his owndevices. Thereafter, it was up to the lad whether he would become a minister or a professor,King’s Magistrate, Chief Warden, or councillor; and the father’s worries about his son wouldbe over. The lad grew up, acquired whiskers, became stout, crammed as he was with food andknowledge, was sealed off hermetically from all worldly temptation, had both body and soultaken care of, was educated in faith and good health, and made a clergyman, professor, King’sMagistrate, Chief Warden, or councillor - in line with his mental faculties or his good luck,without causing the least concern to his father and mother. The College became his mother.This respectable matron had some five or six hundred foster sons and an income of severalhundred thousand forints to pay for their education; it possessed the most learned professors,products of foreign universities; a world-famous library and all kinds of endowments, which,while stimulating the youths to diligence, soon enough instilled in them the salutaryconsciousness of having learnt to earn their own livelihood, modest though it was, accordingto their deserts.The Rector of Nagyenyed College was at that time the Right Honourable Master GersonSzabó of Torda, a great scholar, an exceptionally peaceable gentleman and a tireless upholderof virtuous ways.For, once he had established himself among his monstrous folios, he became so utterlyabsorbed in them that he would often ask his wife whether he had had his dinner, yet to hispupils he was an oracle. His inclinations drew him only towards such quiet and peacefulsciences as astronomy and mechanics, while he had a dislike for history as a science which in his words - taught nothing but the names of men and women who excelled in slaying theirfellow beings, praised the exploits of the sinful, the sanguinary and the ruthless and filled its5District in Transylvania.9

boundless expanse with lies, instead of improving posterity through upholding the example ofpious men, of benefactors of mankind, and of sages.In his repugnance to particular historical personages, he even did not hesitate to falsify thepast for the spiritual welfare of his students, enjoining the professor of history to depictCleopatra, Semiramis and other such shameless hussies, as ugly, detestable monsters, the verythought of whom should be enough to fill one with loathing.Never were the students allowed to cast their eyes upon a female shape; dancing, the sound ofthe fiddle and other vain diversions, were banished once and for all from their midst; even inchurch, to keep them from ogling the girls, a space behind the pews was partitioned off for theolder students, who sat there on trimmed fir trunks, to keep thei

The short stories of Móricz are alternately concerned with idyllic and tragic events. The idyll and tragedy are, of course, the two extreme characteristic forms of the feelings entertained in the period about 1919. By th