Transcription

PLAY INCHILDREN’SDEVELOPMENT,HEALTH ANDWELL-BEINGJEFFREY GOLDSTEINFEBRUARY 2012

ABOUT THE AUTHORJeffrey Goldstein, Ph.D. (J.Goldstein@uu.nl) has been at Utrecht University (Utrecht, TheNetherlands) since 1992. He is currently research associate at the Research Institute forHistory and Culture, Utrecht University. Among his 16 books are Toys, Games and Media(with David Buckingham and Gilles Brougére. Taylor and Francis, 2004), The Handbookof Computer Game Studies (with Joost Raessens. MIT Press, 2005); Toys, Play and ChildDevelopment (Cambridge University Press 1994); and Why We Watch: The Attractions ofViolent Entertainment (Oxford University Press, 1998). In 2011 his chapter on Technologyand Play appeared in A. D. Pellegrini (editor), Oxford Handbook of the Development of Play(Oxford University Press).Goldstein is chairman of the National Toy Council (London. www.btha.co.uk/value of play/toy council.php) and serves on boards of the Netherlands Institute for the Classificationof Audiovisual Media (www.kijkwijzer.nl), and PEGI, the European video games ratingboard (www.pegi.info). He is co-founder with Brian Sutton-Smith and Jorn Steenhold ofthe International Toy Research Association (www.toyresearch.org). In 2001 he receivedthe BRIO Prize (Sweden) for research ‘for the benefit and development of children andyoung people.’ He is on the Editorial Board of Humor: International Journal of HumorResearch and the International Journal of Early Childhood Education.Published in February 2012Design by www.fueldesign.be, BrusselsPrinted on Cocoon silk, 100% recycled

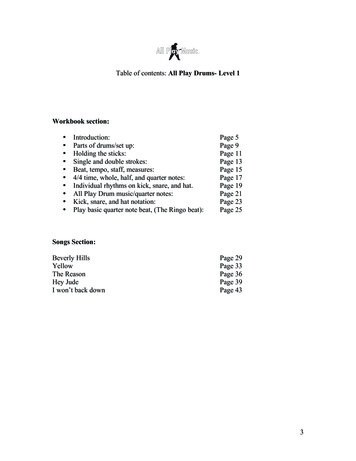

TABLE OF CONTENTSINTRODUCTION31. WHY PLAY IS IMPORTANTPlay and the BrainPlay and Child DevelopmentThe Role of Toys52. VARIETIES OF PLAY93. TALKING, THINKING, CREATINGCognitive DevelopmentLanguage and PlayPlay Promotes Creativity114. PLAYMATESSocial DevelopmentAge-Mixed Playgroups / Intergenerational Play155. SEX DIFFERENCES IN PLAY AND TOY PREFERENCES196. PLAY AND HEALTHObesityActive Play and ADHDPlay and the Quality of Life237. TOO LITTLE PLAY CAN AFFECT CHILD DEVELOPMENTPlay Deprivation278. PLAY AND TECHNOLOGY299. PLAY AND COMMUNITYPlay and Citizenship3310. TO PROMOTE PLAYWhy Toys Are Important37REFERENCES39

PLAY DURINGEARLY CHILDHOODIS NECESSARY IFHUMANS ARE TOREACH THEIRFULL POTENTIAL

3INTRODUCTIONPlay, games and entertainment have occupiedmy research and writing, to say nothing of myleisure time, for the 40 years that I have beena psychologist. One happy result of myinterest in these pleasurable pursuits was aninvitation from Toy Industries of Europe (TIE) toprepare this review of recent research on play.What drives my professional activities is thebelief that people would not devote so muchof their lives to entertaining and enjoyingthemselves if these did not serve somegreater purpose beyond their intrinsic merits.Recent developments in biology, psychologyand neuroscience lend credence to theimportance of play in human evolution anddevelopment. Play may even be thecornerstone of society because it requirescommunication and cooperation amongpeople playing different roles and followingagreed-upon rules. My research has focusedon how our leisure activities can be put togood use in education, business andmedicine, and to improve the quality of life forchildren and adults (see References).Developments in science and technologyhave broadened our views of play. Theflourishing of ‘cognitive neuroscience’ (thestudy of the relationships between brainactivity, thinking and acting) has led to newinsights into the role of biology and the brainin play and toy preferences. The importanceof play for mind and body has been welldocumented.Some research just stops you in your tracks.That is the effect that Melissa Hines andGerianne Alexander’s research had onme. They found that baby vervet monkeysdisplay sex differences in play styles andtoy preferences that mirror those of humanchildren. So it is not only parents’ behaviourand marketing that produce boys’ and girls’different toy preferences. Hormones andgenes also influence children’s play. It seemsthat males, human and nonhuman, areattracted to toys that move.People play because it is fun. One of themany ways in which play is healthy is thatit results in positive emotions, and thesemay promote long-term health. Even if it didnot do this, play improves the quality of life– people feel good while playing. Play hasa major contribution to make in keeping anageing population healthy.Active play has the paradoxical effect ofincreasing attention span and improving theefficiency of thinking and problem solving.Two hours of active play per day may helpreduce attention deficits and hyperactivity.The most striking thing about hi-tech toys isthat the technology does not in itself driveplay. Some modern toys can interact withother toys, with iPads and computers, andcan recognise your voice and learn yourcommands. Yet much of their potential isoverlooked by players. Many children playwith these toys in traditional ways. In thisthey resemble adults who make limited useof their computer software, learning how todo what they want to do with their computersand ignoring the many features that are ofless interest.In the Western world, nearly everyonebelieves that children benefit from free play.Research confirms that children’s selfinitiated play nurtures overall development,not just cognitive development (such aslearning to name colours, numbers orshapes). Abundant research has shownthat play during early childhood is necessaryif humans are to reach their full potential.Parents, teachers and government bodies allrecognise the value of play. Yet opportunitiesfor play continue to diminish, with fewer playspaces, less freedom to roam outdoors, anddecreasing school time for free play. Thecase for play is clear, now the question iswhat do we do to ensure that children get theplay they need and deserve?Jeffrey Goldstein Ph.D.Utrecht University

PLAY IS THELENS THROUGHWHICH CHILDRENEXPERIENCETHEIR WORLDAND THE WORLDOF OTHERS

51 WHY PLAY IS IMPORTANTPlay has been defined as any activity freelychosen, intrinsically motivated, and personallydirected. It stands outside ‘ordinary’ life,and is non-serious but at the same timeabsorbing the player intensely. It has noparticular goal other than itself. Play is not aspecific behaviour, but any activity undertakenwith a playful frame of mind. PsychiatristStuart Brown writes that play is ‘the basis ofall art, games, books, sports, movies, fashion,fun, and wonder – in short, the basis of whatwe think of as civilization.’ (Brown 2009).As the noted play theorist Brian Sutton-Smithremarked, the opposite of play is not work,but depression.All types of play, from fantasy to roughand-tumble, have a crucial role in children’sdevelopment. Play is the lens through whichchildren experience their world, and the worldof others. If deprived of play, children willsuffer both in the present and in the longterm. With supportive adults, adequate playspace, and an assortment of play materials,children stand the best chance of becominghealthy, happy, productive members of society.PLAY AND THE BRAINA behaviour that is present in the young ofso many species must have an evolutionaryadvantage, otherwise it would have beeneliminated through ‘natural selection’. Whatmight be the advantages of play? Playincreases brain development and growth,establishes new neural connections, and ina sense makes the player more intelligent.It improves the ability to perceive others’emotional state and to adapt to ever-changingcircumstances. Play is more frequent duringthe periods of most rapid brain growth.Because adult brains are also capable oflearning and developing new neural circuits,adults also continue to play.Play theorist Brian Sutton-Smith believes thatthe human child is born with a huge neuronalover-capacity, which if not used will die. ‘Notonly are children developing the neurologicalfoundations that will enable problem solving,language and creativity, they are also learningwhile they are playing. They are learning howto relate to others, how to calibrate theirmuscles and bodies and how to think inabstract terms. Through their play childrenlearn how to learn. What is acquiredthrough play is not specific informationbut a general mind set towards solvingproblems that includes both abstractionand combinatorial flexibility where childrenstring bits of behaviour together to formnovel solutions to problems requiringthe restructuring of thought or action A child who is not being stimulated, by being. played with, and who has few opportunitiesto explore his or her surroundings, may failto link up fully those neural connections andpathways which will be needed for laterlearning.’ (Sutton-Smith 1997).In play we can imagine situations neverencountered before and learn from them. Toyaeroplanes preceded real ones.Neuroscientist Jaak Panksepp found thatplay stimulates production of a protein,‘brain-derived neurotrophic factor’, in theamygdala and the prefrontal cortex, whichare responsible for organising, monitoring,and planning for the future. In one study, twohours a day of play with objects producedchanges in the brain weight and efficiencyof experimental animals (Panksepp 2003,Rosenzweig 1976).Play has immediate benefits, such ascardiovascular fitness, and long-termbenefits, including a sense of morality. Anarticle in the American PsychologicalAssociation Monitor on Psychology examinesthe positive effects and utter necessity ofplay. The most common theory is thatjuveniles play at the skills they will need asadults.

6Some newer thinking proposes it is more thanthat. Play seems to have some immediatebenefits, such as aerobic conditioning andfine-tuning motor skills, as well as long-termbenefits that include preparing the young forthe unexpected, and giving them a sense ofmorality. How? Learning to play successfullywith others requires ‘emotional intelligence,’the ability to understand another’s emotionsand intentions. Play helps to level the playingfield and promotes fairness. Justice beginswith healthy social play (Azar 2002).Paediatrician Dr. Ari Brown stressed thatunstructured play time is the best way tostimulate the developing brain. ‘When babiesare engaged in unstructured free play withtoys, they are learning to problem-solve,to think creatively, and develop reasoningand motor skills,’ she said. ‘Free play alsoteaches children how to entertain themselves,which is certainly a valuable skill.’ (AmericanAcademy of Pediatricians 2011).PLAY AND CHILDDEVELOPMENTPlay is essential to development because itcontributes to the cognitive, physical, social,and emotional well-being of children andyouth. Play also offers an ideal opportunityfor parents to engage fully with their children.Despite the benefits derived from play for bothchildren and parents, time for free play has beenmarkedly reduced. Children today receive lesssupport for play than did previous generationsin part because of a more hurried lifestyle,changes in family structure, and increasedattention to academics and enrichmentactivities at the expense of recess or free play.What are the benefits of play in a child’slife? According to play therapist O. FredDonaldson, a child who has been allowedto develop play resources receives manyenduring advantages. She develops auniversal learning skill. Play maximises herpotential by developing creativity andimagination. Play promotes joy, which isessential for self-esteem and health. Thelearning process is self-sustained based as itis on a natural love of learning and playfulengagement with life. oural benefits of play Play reduces fear, anxiety, stress, irritability Creates joy, intimacy, self-esteem andmastery not based on other’s loss ofesteem Improves emotional flexibility andopenness Increases calmness, resilience andadaptability and ability to deal with surpriseand change Play can heal emotional pain.Social benefits of play Increases empathy, compassion,and sharing Creates options and choices Models relationships based on inclusionrather than exclusion Improves nonverbal skills Increases attention and attachmentPhysical benefits Positive emotions increase the efficiencyof immune, endocrine, and cardiovascularsystems Decreases stress, fatigue, injury, anddepression Increases range of motion, agility,coordination, balance, flexibility, and fineand gross motor exploration

7A review of more than 40 studies found thatplay is significantly related to creative problemsolving, co-operative behaviour, logicalthinking, IQ scores, and peer group popularity.Play enhances the progress of earlydevelopment from 33% to 67% by increasingadjustment, improving language and reducingsocial and emotional problems (Fisher 1992).As the developmental biologist Jean Piagetobserved, ‘We can be sure that allhappenings, pleasant or unpleasant, in thechild’s life, will have repercussions on herdolls’ (Piaget 1962).THE ROLE OF TOYSIn addition to being purpose-built for children’splay, toys invite play and prolong play.Children will play longer when suitable playobjects are available, and stand to gain thegreatest benefits that play has to offer.According to research conducted in homes,the two most powerful factors related tocognitive development during infancy andthe preschool years are the availability ofplay materials and the quality of the mother’sinvolvement with the child.The availability of toys in infancy is related tothe child’s IQ at three years of age. Childrenwith access to a variety of toys were found toreach higher levels of intellectual achievement,regardless of the children’s sex, race, or socialclass (Bradley 1985, Elardo 1975).In one study, the availability of toys intendedfor social play increased social interaction bydisabled children in an inclusive preschool(Driscoll 2009).It is abundantly clear that play is ofvital importance in children’s health anddevelopment, and in becoming responsiblecitizens. Yet despite the wide spread beliefthat play is beneficial to children, opportunitiesand encouragement for free play areincreasingly limited. Among child developmentexperts and education professionals thereare growing calls for reintroducing play intoearly childhood education (Elkind 2007,Fisher 2011).YOU CAN DISCOVERMORE ABOUT A PERSONIN AN HOUR OF PLAYTHAN IN A YEAR OFCONVERSATION.Plato

EARLY PLAYEXPERIENCESSET THESTAGE FOR ALLSUBSEQUENTDEVELOPMENT

92 VARIETIES OF PLAYIt is widely accepted that play changesacross early childhood. The infant’s firstexperiences of play are when adults try toelicit smiling and laughter through tickling, orplaying peek-a-boo. But these are notinitiated by the infant and do not constitutetrue play. Baby’s first play is solitary, exploringobjects in her surroundings. Toddlers canexperiment with their environment (‘exploratoryplay’) while older children can manipulate andcontrol their environment (‘mastery play’).Solitary play is followed by parallel play playing ‘next to’ but not ‘with’ other children- at around two or three years of age. Thissets the stage for social play, at around agethree or four. Social play is diverse andcomplex, and includes everything from simpleactivities, like working together to build asand castle, to ‘rough-and-tumble’ play(chasing, play fighting), and complex ‘sociodramatic play’, in which children enact rolesin fantasy scenarios that they themselvescreate.This sequence of play development, whichextends from solitary exploration tosensorimotor play to pretend play, hasreceived extensive empirical support andcorrelates with children’s cognitive abilities(Brown 2009, Else 2009, Smith 2010). Theemergence of pretend play, in particular, isa critical achievement of toddlers as itallows them to practice symbolic thought.Virtually every aspect of the growing child’slife is affected by play. Early play experiencesset the stage for all subsequent development.For example, being able to substitute oneobject for another – using a sponge as a‘boat’ in the bath – is a necessary step inlanguage development, where words standfor something other than themselves.A study by Levine, Huttenlocher and Cannon(2011) examined the relation between children’searly puzzle play and their spatial skill.Individual differences in spatial skill emergeprior to preschool entry.However, little is known about the earlyexperiences that may contribute to thesedifferences. 53 children and parents wereobserved at home for 90 minutes every fourmonths (six times) between the ages of twoand four years. When children were four anda half years old, they completed a spatialtask involving mental transformations oftwo-dimensional shapes. Children who wereobserved playing with puzzles performedbetter on this task than those who didnot, controlling for parent education andincome. Among those children who played withpuzzles, frequency of puzzle play predictedperformance on the spatial transformationtask.By preschool age, children’s imagination,language, and communication skills permitcommunicating about social pretend play.Children can plan and manage their fantasyplay easily and can modify the script as itprogresses. During social play childrenacquire knowledge and information (such ascolour names and word spelling), learnpersonal limits and social rules. Social playrequires the play partners to share the sameunderstanding of the situation, to agree onthe rules of play. A ‘tea party’ requires thechildren to agree on the imaginary scene, andto pretend that there is tea in the emptyteapot and tea cups.Children benefit most by varying their playactivities, sometimes playing alone but alsowith others, playing quietly on the floor aswell as actively outdoors. In order to stimulateand prolong play, adults should support andencourage it by providing sufficient spacein which to play, and a broad assortment oftoys and other play objects to enable thebroadest range of play possibilities. This willensure that neural pathways in the brainare developed and strengthened, that everymuscle is exercised, and that great feats ofimagination are displayed.

PLAYINGWITH BLOCKSPROMOTESLANGUAGEDEVELOPMENT

113 TALKING, THINKING,CREATINGThe growing child learns nearly everythingthrough play. Play helps build stronglearning foundations because later levels oflearning are built upon earlier ones, a processreferred to as ‘scaffolding’. The qualities ofspontaneity, wonder, creativity, imagination,and trust, are best developed in earlychildhood play. In play, the learning process isself-sustained because the natural love oflearning is preserved and strengthened. Thepower of play also enhances self-esteem andinterpersonal relationships.COGNITIVEDEVELOPMENT ANDLANGUAGEThe cognitive processes involved in playare similar to those involved in learning:motivation, meaning, repetition, self-regulation,and abstract thinking. Contemporary toys andgames, by virtue of their electronic functionsand possibilities, invite exploration anddiscovery - learning activities par excellence.Attention is essential for reading and for manykinds of learning and performance. Attentionspan during free play depends almost solelyon the type and number of toys available(Moyer 1955).Children’s explorations during free playsupport learning (Schulz 2008). The abilityto read, speak and do maths ultimately restsupon the child’s capacity to use symbols,for example, a block to represent a truckor a telephone. Play at an early age (1324 months) facilitates language (Hall 1991,Ungerer 1986).Various forms of pretend play can enhanceschool readiness, social skills, and creativeaccomplishment.Children’s early exposure to and participationin pretend play in the preschool years isrelated to their emergent literacy skills whenthey reach kindergarten (Katz 2001, Roskos2007, Singer 2002).Children’s toys provide a rich arena forinvestigating causal understanding becauseobjects are understood at different levels ofabstraction. For example, many dolls andaction figures can be construed either ascharacters from a fictional world or asphysical objects in the real world. In twoexperiments, 72 four and five year oldsunderstood that characters shared certainproperties even though they did not have thesame name. Children’s understanding of anobject’s abstract character identity enabledthem to use it in multiple ways (Rhemtulla2009).‘Children at play begin to learn essential mathskills such as counting, equality, additionand subtraction, estimation, planning,patterns, classification, volume and area,and measurement. Children’s informalunderstanding provides a foundation onwhich formal mathematics can be built’(Fisher 2011, p. 344).Researchers, educators, and parents havelong believed that children learn cause andeffect relationships through exploratory play.In one study, four to five year olds explorednovel toys in an effort to understand how theywork (Schulz 2007).‘To learn in a formal school environment,children must be able to regulate theirbehaviours and emotions and communicateand engage with others in sociallyappropriate ways. Research clearly highlightsa relationship between playful learningexperiences, social and self-regulatory skills,and academic achievement’ (Fisher 2011).

12‘Playful learning’ refers to the use of freeplay and adult-guided play activities topromote academic and social skills (Fisher2011). For example, Montessori schoolscreate classrooms in which children choosefrom a number of playful activities that havebeen prearranged by adults. Research showsthat Montessori kindergarten children aresignificantly more likely to use a higher levelof abstract reasoning by referring to justice orfairness to convince another child to relinquishan object, and are more likely to be involvedin positive shared peer play than are childrenfrom traditional schools (Lillard 2006).LANGUAGE AND PLAYStudies from many countries show arelationship between early social playand later communication skills. Maternalresponses to infant toy initiations, as wellas manipulation and labelling of toys at age11 months were related to infant languageat 14 months. In Finland, Lyytinen (1999)reported that symbolic play at age 14 monthspredicts children’s development at the age oftwo years.Playing with blocks promotes languagedevelopment. In one study, children agedone and a half to two and a half who wereprovided with sets of moulded plastic buildingbricks with which to play had significantlyhigher language scores six months later,compared with a control group (Christakis2007).Gunhilde Westman of Uppsala University(Sweden) sees play as an arena fordeveloping language and communication.Play is demanding for children because theyhave to pay attention to each other’s wordsand actions. They have to concentrateon their own use of language in orderto communicate clearly. Children learnthese by listening to each other when theyplay. Through play children learn to reachagreement and to reciprocate words andactions. One of the functions of preschoolsand schools is to educate children to becomecitizens who can participate in discussionsand reach mutual agreements. Westman(2003) believes there may be a link betweenchildren’s confidence and motivation whenplaying, and their language development.Children who are motivated by play andtry to expand their play actions tend to bemore linguistically developed and confident.Much research has pointed to the importanceof children’s negotiations in peer pretend playfor preschool children’s social, cognitive andliteracy development. However, few studieshave investigated the relations betweentalk about play in preschool and children’slanguage skills when entering school. In astudy by Rydland (2009), a group of childrenfour to five years old, who had Turkish as theirfirst language and Norwegian as their secondlanguage, was followed for two years, frompreschool to first grade, and videotapedin play with peers. In the first part of theanalysis, relations between talk about playin preschool and vocabulary skills andstory comprehension in first grade wereinvestigated. The main findings indicate thatpreschool children’s talk about their play isrelated to language skills in first grade.

13PLAY PROMOTESCREATIVITYCreativity increases following free play.According to research by Anthony Pellegrini,providing children with play breaks duringthe school day maximises their attention tocognitive tasks (Pellegrini 2005).Children produced more colourful andcomplex art after being allowed to play,compared to children who first followed astructured exercise. Fifty-two English schoolchildren six to seven years old were randomlyassigned to two groups. The first groupwas allowed to play for 25 minutes, whilethe other group copied text from the board.All children were then asked to produce acollage of a creature, using a controlledrange of tissue-paper materials. Ten judgesassessed the creative quality of the resultingwork. The range of colours and total numberof pieces used by each child was recorded.The results revealed a significant positiveeffect of unstructured play upon creativity(Howard-Jones 2002).When four to five year old children wereasked to ‘play with’ or ‘to remember’ 16common objects, they recalled the itemsbetter when instructed to play with, ratherthan to remember them (Newman 1990).Adults, too, are more creative when theyimagine themselves as children at play. Withthe responsibilities of adulthood, playfulcuriosity is sometimes lost. In a 2010 studyby Zabelina and Robinson, 76 universitystudents were randomly assigned to one oftwo conditions before creative performancewas assessed with a version of the TorranceTest of Creative Thinking. In a controlcondition, participants wrote about what theywould do if school was cancelled for the day.In an experimental condition, the instructionswere identical except that participantswere to imagine themselves as seven yearolds in this situation. Individuals imaginingthemselves as children subsequentlyproduced more original responses on thetest of creativity. Further results showed thatthe manipulation was particularly effectiveamong more introverted individuals, whoare typically less spontaneous and moreinhibited in their daily lives. The resultsestablish that there is a benefit in thinkinglike a child for subsequent creative originality,particularly among introverted individuals.In A Mandate for Playful Learning in Preschool:Presenting the Evidence, a review of playresearch confirms that children’s self-initiatedplay nurtures overall development, not justcognitive development (such as learning toname colours, numbers, or shapes).In fact, research builds a very strong casethat childhood play is a required experience inorder to become a civilised, fully-realisedhuman being (Hirsh-Pasek 2006). Abundantresearch has shown that play during earlychildhood is necessary if humans are to reachtheir full potential. For children, and in fact,for society’s well-being, true play is a criticalneed, not a fanciful frill. And so it requiresearly childhood programmes to advocate forand insist upon including play as part of theirdaily curriculum and teaching strategy(Stevens 2009).

CHILDREN’SFIRST STEPSTOWARDINDEPENDENCECOME WITH THEIRATTACHMENT TOSOFT CLOTHESOR FURRY TOYS

154 PLAYMATESThe infant’s first experiences of play are withparents and siblings, who try to elicit interestand laughter from baby. Play helps infantsand toddlers gain a sense of independenceand identity. Their first steps towardindependence come with their attachmentto soft clothes or furry toys. Children with‘transitional objects’ which they cling toat bedtime or when distressed have fewersleep disturbances and are reported in threeout of four studies to be more agreeable,self-confident, and affectionate (Litt 1986,Singer 1990, Winnicot 1971).As infants develop, their social play developswith them: At six months, babies tend to bepassive; the adult must do all the work.At around six months the infant is able tosustain interest in the performance of theadult but remains passive. At about ninemonths, the infant can initiate the game butthere is no evidence of taking turns in thegame. Beginning at about one year of age,when the infant shows awareness of thedifferent play roles, infants will alternate withtheir mothers shifting from agent to recipient.In the second year toddlers can createvariations within the game, showing anunderstanding not only of its basic structure,but its limits and possibilities. Examples arerolling a ball back and forth, and peek-a-boo.During play children form enduring bonds offriendship, including with their adult playmates(Goldstein 1996, Mos and Boodt 1991).Children age five to seven years with proficientpretend play skills are socially competent withpeers and are able to engage in classroomactivities. Children who scored poorlyon the play assessment were more likely tohave difficulty interacting with their peersand engaging in school activities. Socialcompetence is related to a child’s ability toengage in pretend play (Uren 2009).Psychiatrist Stuart Brown (2009) discoveredthat the absence of social play was a commonlink among murderers in prison. They lackedthe normal give-and-take necessary forlearning to understand others’ emotionsand intentions, and the self-control that onemust learn to play successfully with others.Some toys promote social play. Two to sixyear olds at day-care and nursery centres inNashville, Tennessee, were observed duringplay. Dress-up clothes, toy wagons, ballsand a puppet stage were far more likely tobe played with in co-operative social playthan were puzzles, a toy sink and pull toys,all of which were used primarily in isolatedplay (Hendrickson 1981).Isn’t play naturally competitive? Doesn’tcompetition help children better learn tocompete in the adult world? Play isn’tnaturally competitive. In fact, it is the opposite- naturally cooperative. Ch

all art, games, books, sports, movies, fashion, fun, and wonder – in short, the basis of what we think of as civilization.’ (Brown 2009). As the noted play theorist Brian Sutton-Smith remarked, the opposite of play is not work, but depression. All types of play, from fantasy to rough-a