Transcription

Leading for ChangeA blueprint for cultural diversityand inclusive leadershipJuly 2016

Australian Human Rights Commission 2016.The Australian Human Rights Commission encourages the dissemination and exchange of information presented in this publicationand endorses the use of the Australian Governments Open Access and Licensing Framework (AusGOAL).All material presented in this publication is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence, with theexception of: photographs and images; the Commission’s logo, any branding or trademarks; where otherwise indicated.To view a copy of this licence, visit de.In essence, you are free to copy, communicate and adapt the publication, as long as you attribute the Australian Human RightsCommission and abide by the other licence terms.Please give attribution to: Australian Human Rights Commission 2016.Leading for Change: A blueprint for cultural diversity and inclusive leadershipISBN 978-1-921449-78-9AcknowledgementsThe Working Group thanks Nick Kaldas APM, who was a member of the group until March 2016. Dr Andreea Constantin providedresearch assistance, with the support of the University of Sydney Business School. Thanks also to Ting Lim, Katherine Samiec, KatieEllinson, Britt Jacobsen and Evie Watt for their contributions to this work.

‘This Blueprint will help Australian businesses to see what bestpractice looks like when it comes to cultural inclusion. We think thatthe Blueprint will have a powerful impact in the community ’Brian Hartzer, CEO, Westpac Group‘Diversity is a priority for PwC because it’s the right thing to do, andbecause it makes business sense. We’re proud to have contributedto this blueprint – it will be a game-changer for organisationslooking to make a difference on cultural diversity.’Luke Sayers, CEO, PwC Australia‘What I would hope for in ten years time is that we wouldn’t needto be having the conversation around the importance of culturaldiversity in leadership because it would be so inherent in the waywe do business.’Andy Penn, CEO, Telstra‘The University of Sydney Business School is proud to be part of theBlueprint project. This work will enhance understanding of culturaldiversity, and challenge organisations to develop and practiseinclusive leadership.’Greg Whitwell, Dean, The University of Sydney Business School

LEADING FOR CHANGEA blueprint for cultural diversityand inclusive leadershipWorking Group on Cultural Diversity and Inclusive Leadership

Cultural Diversity and Inclusive LeadershipWorking Group MembersDr Tim SoutphommasaneAustralia’s Race Discrimination CommissionerAustralian Human Rights CommissionProfessor Greg WhitwellDeanUniversity of Sydney Business SchoolAssociate Professor Rae CooperAssociate DeanUniversity of Sydney Business SchoolMs Ainslie Van OnselenDirector, Women’s Markets, Inclusion and DiversityWestpac GroupMr Ken WooPartner, Cultural Diversity and Inclusion LeaderPwC AustraliaMr Troy RoderickGeneral Manager, Diversity and InclusionTelstravi

ContentsExecutive summary2FiguresIntroduction4Foreign-born populations in OECD countries5Cultural diversity and inclusive leadership5An applied view of inclusion89Cultural diversity and financial performance10Generating change on cultural diversity11The case for changeThe way forward11Measuring cultural diversity15Dealing with bias and discrimination21Professional development:cultivate diverse leaders25TablesCultural backgrounds of Australia’s senior leaders‘Cultural’ behaviours of professionals722AppendixCase studiesMethodology: classifying Australianleaders’ cultural backgroundsDiversity and inclusion councils and boards1329MasterCard’s Ajay Banga14Classifications29Our process of classification30Australian Bureau of Statistics’ Standardson Cultural Diversity16Peer review30Different international approaches in data collection17Limitations31How to collect data on cultural diversity18Cultural background v cultural identity31Workplace Cultural Diversity Tool19PwC’s cultural diversity targets20Facebook22University of Sydney Business School’s Bachelorof Commerce degree and ‘inclusive leadership’23Telstra’s ‘Bias Interrupted’ program24Scholarships for cultural diversity26Bernard Tyson27Westpac’s Employee Action Groups28Leading for Change vii

Dr Tim SoutphommasaneAustralia’s Race Discrimination CommissionerForewordIn our multicultural society, why don’t we see more diversity among our leaders? Do we haveleadership that is fit for today’s Australia?Holding up a mirror to ourselves isn’t easy. We don’t always do well with self-examination.But improvement never comes without accepting that we can do better.Our conversations about cultural diversity must be conducted in this spirit. They should be guidedby ambition and aspiration. Doing better is about us fulfilling our potential – as individuals, asorganisations, as a society.At the same time, these conversations require an honest recognition. Attitudes and cultures will haveto change – but change won’t be inevitable. It may be resisted. Overcoming this requires not onlytalk, but also action. Good intentions must be turned into staunch commitment.In June 2015, I invited members of the business and academic community to join me in leading thischange. The Working Group on Cultural Diversity and Inclusive Leadership was formed. Consistingof the Australian Human Rights Commission, the University of Sydney Business School, Westpac,PwC Australia and Telstra, the group is responsible for authoring this blueprint.Our task was to develop a blueprint to guide organisations on how they could improve therepresentation of cultural diversity in leadership. We recognised at the time that there were significantgaps in data and considerable uncertainty about what works. We hope that this blueprint capturesthe status quo, and gives clarity to why and how Australia must do better.During the past year, it has been a privilege to chair the Working Group. I thank the contributionsof the group’s members: Professor Greg Whitwell, Associate Professor Rae Cooper, Ainslie VanOnselen, Ken Woo, Troy Roderick. Prior to his retirement from the NSW Police Force as DeputyCommissioner, Nick Kaldas APM was also a member.May we see more leaders now join us in making the case for change.Dr Tim SoutphommasaneRace Discrimination CommissionerAustralian Human Rights CommissionJuly 2016Leading for Change 1

Executive summaryCurrent representationof cultural diversityLeading for Change starts the conversationabout improving the representation of culturaldiversity within Australian leadership. It providesguidance for how organisations can nurtureleadership that is fit for our multicultural societyand our global economy.Australia’s multiculturalism is self-evident.About 28 per cent of our population was bornoverseas, with another 20 per cent havingan overseas-born parent. According toone estimate, 32 per cent of the Australianpopulation have a non-Anglo-Celticbackground. However, such cultural diversity isnot proportionately represented within the seniorleadership of our organisations.This blueprint is the product of a working groupconvened by Race Discrimination CommissionerTim Soutphommasane. The group consists ofthe Australian Human Rights Commission, theUniversity of Sydney Business School, Westpac,PwC Australia and Telstra. Together, the groupshares its experiences in embracing culturaldiversity and inclusive leadership.This blueprint provides, for the first time,a snapshot of the cultural composition ofsenior leaders in Australian business, politics,government and civil society. It finds that theethnic and cultural default of leadership remainsAnglo-Celtic. Australian society may not bemaking the most of its diverse backgrounds andtalents, as figures in the following table indicate.Leading for Change deals with thefollowing issues: the current representation of culturaldiversity within the leadership ofAustralian organisations; the case for changing the status quo; and how organisations can improve theirperformance on cultural diversity andinclusive leadership.Table: Cultural backgrounds of Australia’s senior leaders (in percentage 6.6218.414.98Federal parliament (MPsand Senators)1.7778.7615.933.54Federal ministry (Ministers andAssistant Ministers)2.3885.7111.900Federal and state public service(Secretaries and heads ofdepartments)0.8182.2615.321.61085.0015.000ASX 200 (CEOs)Universities (Vice-chancellors)2

The case for changeAccountability and targetsThe case for cultural diversity can beemphatically made. Simply put, a more diverseworkforce makes for better decision-making.There is mounting evidence that more diverseorganisations achieve better performance.To generate lasting change, cultural diversityneeds to be embedded in an organisation’sgoals, strategy and performance. A strongcase exists for including realistic andachievable targets as part of one’s diversityand inclusion policies.There may also be costs to organisations thatfail to practise inclusive leadership. A failure tochange can result in decreased productivity, ahigher level of turnover and absenteeism andreduced job satisfaction among staff. Then thereis reputational damage that can be caused byracial discrimination.The way forwardLeading for Change proposes actions in threerespects: leadership; systems; and culture.Leadership: senior leaders must have‘skin in the game’Those leaders who are most successful inadvancing diversity understand it both as amoral and business imperative: as somethingto be done because of their personal valuesand because their companies need it to becompetitive. They also get involved in startingconversations and sending signals to createmomentum to improve cultural diversity andinclusion in leadership.Dealing with bias and discriminationOur judgements about leadership may beparticularly susceptible to bias. When itconcerns advancement within professionallife, prejudice can trump diversity. Counteringbias and discrimination requires more than justconsciousness raising – it also requires trainingand education.Professional development: cultivatingdiverse leadersOrganisations may need to redefine theirassumptions about leadership. Promotinginclusive leadership means that people do notend up privileging certain cultural groups overothers because of assumptions about whatleadership must look and sound like. This canbe done through identifying diverse talent,mentoring and sponsorship, and empoweringtalent through professional development.Measuring cultural diversityGathering and reporting data on culturaldiversity must accompany any leadershipcommitment to the issue. Doing so gives abaseline for measuring future progress. It alsohelps to focus minds within organisations.We understand that measuring cultural diversityis complex but this does not mean we shouldavoid doing so.Leading for Change 3

IntroductionAustralia is often described as a multiculturalsuccess story. We rightly celebrate our culturaldiversity. Yet our diversity is not reflected in theranks of leadership within society.Improving the representation of diversity isboth a civic and business concern. The caseis not only about living up to our egalitarianism,but also about securing our future prosperity.No society can reach its full potential unlessits members have the opportunity to realisetheir talents. Few now dispute that companiesand countries are competing for brainpowerand human talent.Leading for Change starts the conversationabout bridging this gap between diversityand leadership. It provides guidance for howorganisations can nurture leadership that is fitfor our multicultural society and global economy.The authors of Leading for Change aremembers of a working group established byAustralia’s Race Discrimination Commissionerin 2015. The group consists of the AustralianHuman Rights Commission, the Universityof Sydney Business School, Westpac, PwCAustralia and Telstra. Together, the group sharesits experiences in embracing cultural diversityand inclusive leadership.4Leading for Change proceeds in three parts.The first looks at the current representationof cultural diversity in senior leadership. Thesecond outlines the case for changing the statusquo. The third explores steps organisations cantake to improve their performance on culturaldiversity and inclusive leadership.We find that there remains a limited level ofcultural diversity represented in the leadershipof Australian organisations and institutions. Theethnic and cultural default of leadership remainsAnglo-Celtic.The case for change is supported by researchindicating the costs of bias and benefits ofdiversity. We recommend organisations shouldconsider sending signals on cultural diversity:making a leadership commitment, collectingmore comprehensive data, setting leadershiptargets, introducing better accountability, andenhancing professional development.Progress takes time – and demands leadership.We trust that Leading for Change will help startcultural change in your organisation.

Cultural diversity and inclusive leadershipDiversity refers to the differences that distinguishgroups of people from one another. Peoplemanifest differences through attributes suchas ethnicity, gender, age, disability, class andsexual orientation. This blueprint is concernedonly with cultural diversity – those differencesthat relate to race, ethnicity, ancestry, language,and place of birth.In Australia, we commonly understand culturaldiversity in terms of the social changes that haveoccurred because of immigration. Today’s mixof ethnic and cultural backgrounds is the resultof successive waves of immigration since theend of the Second World War. A reference to‘culturally diverse’ backgrounds is frequently ashorthand for ‘non-Anglo-Celtic’ ones, thoughit can more specifically refer to those that are‘non-European’.or languages spoken. In our everyday lives, itis also something we see on the faces of thosewe meet and hear in the accents of those withwhom we speak.On various measures, Australia is amongthe most culturally diverse in the world.Our population is drawn from more than300 ancestries. About 28 per cent of people inAustralia were born overseas, with an additional20 per cent having a parent born overseas.1While there are no official statistics on the ethniccomposition of the Australian population, it isnotable that close to 20 per cent of peoplespeak a language other than English at home.2One study estimates that about 32 per cent ofthe general population have a non-Anglo-Celticbackground, with more than 10 per cent of thepopulation having a non-European background.3There is no one simple way of capturingAustralia’s cultural diversity. Cultural diversitycan be revealed through names, places of birthFigure 1: Foreign-born populations in OECD countries (as nd2320201510121350UnitedKingdomUSACanadaIsrael1. Source: OECD Data4Leading for Change 5

Australia’s cultural diversity has been asource of national strength. It has enrichedthe national culture and identity. It has beenaccompanied by a high degree of social mobilityand integration. The children of immigrants onaverage outperform the children of Australianborn parents in educational attainmentand employment.5Such outperformance, however, does notextend all the way to the top. Cultural diversityis nowhere near proportionately representedwithin positions of senior leadership. There areclear limits to Australian society’s boast that it isdiverse and multicultural.‘Cultural diversity is nowhere nearproportionately represented withinpositions of senior leadership.’In preparing Leading for Change, we conductedresearch into the cultural composition ofsenior leaders in Australian business, politics,government, and civil society. Our attentionwas confined primarily to the ranks of chiefexecutives and equivalents. To some extent, thiswas due to the difficulties in studying the culturalbackground of organisational leaders at levelsbelow the very top. As there remains limiteddata collected about cultural diversity, focusingattention on chief executives gave us the bestprospect of generating credible data.Our method involved two stages. First, weidentified senior leaders’ cultural background.Second, we categorised them according towhether they have an Indigenous background,Anglo-Celtic background, European (nonAnglo-Celtic) background, or non-Europeanbackground.6 The resulting statistics gave us thenumerical state of play for the representation ofcultural diversity.We found a bleak story for multicultural Australia.In corporate Australia, the ranks of seniorleaders remain overwhelmingly dominatedby those of Anglo-Celtic and Europeanbackground. Among the 201 chief executivesof ASX 200 companies, 77 per cent have anAnglo-Celtic background and 18 per cent havea European background. Only 10 chief6executives – or five per cent – have a nonEuropean backgrounds. None of the 201 chiefexecutives has an Indigenous background.Such findings are corroborated by DiversityCouncil Australia (DCA). According to DCA,while about 32 per cent of the generalAustralian population are culturally diverse(i.e. have a ‘non-Anglo-Celtic’ background),only 22 per cent of chief executives fallinto this category. There was particularlylow representation of those who have anAsian background.7Similar patterns prevail elsewhere. In theAustralian parliament, 79 per cent of the226 elected members in the House ofRepresentatives and the Senate have anAnglo‑Celtic background. Sixteen per cent havea European background. Those who have anon-European background make up less thanfour per cent of the total, while those whohave an Indigenous background comprise justunder two per cent.8Cultural diversity is even lower within the ranksof the federal ministry. Of the 42 members ofthe ministry, 86 per cent have an Anglo-Celticbackground, 12 per cent have a Europeanbackground; there is one member of theministry who has an Indigenous background(two per cent), though none who has a nonEuropean background.9In the Australian public service, diversity isalso dramatically under-represented. Of the124 heads of federal and state departments,it is notable that there are only two who havea non‑European background (less than twoper cent) and one who has an Indigenousbackground (less than one per cent).Eighty-two per cent of departmental headshave an Anglo-Celtic background, with15 per cent having a European background.Among our universities, it is much thesame – and in some respects worse. All ofthe 40 university vice-chancellors either havean Anglo-Celtic background (85 per cent) ora European background (15 per cent). Thereis not one vice-chancellor who has either anIndigenous or non-European background.

Table 1: Cultural backgrounds of Australia’ssenior SX 200 CEOs76.6%18.4%5.0%Federal Parliamentarians78.8%15.9%1.8%3.5%Federal Ministry85.7% 11.9%2.4%Federal and State Public Service Heads82.3% 15.3%0.8%1.6%University Vice-Chancellors85.0%15.0%Australian society may not be making themost of its cultural diversity. The reasonsfor this are various, but include bias anddiscrimination. Professionals from culturallydiverse backgrounds report that organisationsunderstand leadership in ways that privilege‘Anglo’ cultural styles.10 International researchon leadership and race also suggests thatin predominantly ‘white’ work environments,leaders who are ‘people of colour’ may facedisadvantages because they are not perceivedas legitimate and because power inequities inorganisations privilege ‘whiteness’.11Laws do exist against discrimination inemployment. At the federal level, the RacialDiscrimination Act prohibits unfavourabletreatment because of race, colour, ethnicity ornational origin. Various legislation also existsat the state and territory levels.Getting the most out of cultural diversity,however, requires more than just having laws orrules in place. It is broadly recognised that whatis required is a ‘culture of inclusion’. This is aculture in which differences are recognised andvalued, and in which different voices are heard indecision making.12As described by Catalyst, employeesexperience inclusion within the workplacewhen they simultaneously feel both a ‘sense ofuniqueness’ and a ‘sense of belongingness’.These refer, respectively, to employees feelingrecognised and valued for their distinct talentsand perspectives, and to seeing themselvesas ‘insiders’ who share common goalswith colleagues.13Within this context, ‘inclusive leadership’ refersto some of the attributes that leaders can adoptin order to promote inclusion. For example,Catalyst identifies four such behaviours –empowerment, humility, courage andaccountability – which contribute to employeesfeeling a sense of ‘psychological safety’,and reporting a greater sense of uniquenessand belongingness.14 Elsewhere within theliterature, inclusive leadership is understoodto mean that a leader ‘supports all individualmembers of groups to express their opinions,with emphasis on those who would not usuallyhave their voices heard’.15Leading for Change 7

This paper adopts an applied view of inclusiveleadership. It proposes that organisations thatare inclusive of cultural diversity must meettwo requirements. First, if employees are tobe valued for their ‘uniqueness’, it shouldfollow that leadership may also come in morethan one form. Leadership may, that is, lookand sound different from an Anglo-Celtic or‘white’ (and male) norm. Second, any notion of‘belongingness’ should also extend to positionsof leadership. Those of culturally diversebackgrounds should not feel excluded from thesenior echelons of their organisations, as thoughthey are perennial outsiders.Inclusive leadership, then, means that the ranksof leadership must include cultural diversity.A commitment to cultural diversity must involvea preparedness to change the status quo ofcultural representation.Figure 2: An applied view of oyees feel recognised and valued fortheir distinctive qualitiesEmployees share common goalswith colleaguesLeadershipPeople and systems within an organisationunderstand that leadership may comein more than one cultural form (everyleader is unique)People and systems within an organisationbelieve that the ranks of leadership shouldbe open to all (those of culturally diversebackgrounds will feel that they can belongwithin the ranks of leadership)8

The case for changeSome may argue the under-representation ofcultural diversity in leadership is not a problem.It may simply reflect the relatively short amountof time that Australian society has beenmulticultural. With time, we may well see anatural improvement.Such arguments are familiar. Also familiarare suggestions that a principle of meritshould guide decisions about appointmentand promotion. According to this view,taking an active concern with representationelevates equality of outcomes above equalityof opportunity.It may be comforting to believe thatdecisions in organisations are guidedpurely by considerations based on merit.Yet a considerable body of research nowdemonstrates that we are not always perfectlyrational – that biases can affect our decisionmaking, as individuals and as organisations.16This does not deny the appeal of a meritocraticideal or the idea of ‘careers open to talents’. Itis a modern aspiration to have a society whereappointments go to the most qualified, andnot to those who come from the right familiesor have the right background. It is just that theideal is not always realised in practice. The levelplaying field presumed by meritocracy does notalways exist.The current representation of cultural diversityin positions of leadership may reflect someimpediments to equal opportunity. And, ifsuch impediments do exist, it may indicatethat we have a problem of unfulfilled talent.Organisations may not be promoting the bestpeople; opportunities for growth and innovationmay be squandered.In a notable study, economist Scott E. Pagefound that a group drawn from a diverse poolof people was superior to a group drawn fromtalented individual thinkers in solving difficultproblems.17 The reason is that a unique kind oflearning takes place when people from differentbackgrounds come together, one that doesnot occur within groups that are homogenous.Experiences with diversity – including culturaldiversity – are associated with improvedcognitive skill and intellectual self-confidence.18‘ a more diverse workforcemakes for better decision‑making.’There is mounting evidence that more diverseorganisations achieve better performance.Analysis conducted by McKinsey, for example,indicated a positive relationship between a morediverse leadership team and better financialperformance. In a study of 366 companies fromthe United Kingdom, Canada, Latin Americaand the United States, McKinsey found thatcompanies in the top quartile of cultural diversitywere 35 per cent more likely to have financialreturns above the national industry median.The findings of the study also indicated therelative scale of gains that accrue from culturaldiversity. Companies in the top quartile forgender diversity were 15 percent more likelyto have financial returns above their respectivenational industry medians.19 At least on theevidence of this study, the benefits of culturaldiversity may be even greater than thosegenerated by gender diversity.The case for cultural diversity can beemphatically made. Simply put, a more diverseworkforce makes for better decision-making.Leading for Change 9

Figure 3: Cultural diversity andfinancial performance – How diversitycorrelates with better financial performanceLikelihood of financial performance above national industrymedian, by diversity quartile %Gender diversity60 15%5040544730201004th quartile1st quartileEthnic diversity7060 35%5040584330201004th quartile1st quartileSource: McKinsey Diversity DatabaseOther evidence backs such findings. A study oftalent and growth by economists in the UnitedStates suggested that up to 20 per cent ofproductivity growth in the US from 1960-2008can be attributed to a reduction in discrimination(sex – and race-based). Another American studyindicated that every 1 per cent rise in genderand ethnic diversity results in 3 to 9 per cent risein sales revenue.2010A different way of understanding the matteris in terms of cost. If under-representation ofcultural diversity in leadership is symptomaticof bias and discrimination, this is not without itsconsequences. While there is limited researchthat has authoritatively quantified the financialcost of racial discrimination to society at large,they are likely to be substantial.21At the organisational level, the nature of the costcan be various: decreased productivity, a higherlevel of turnover and absenteeism, reducedjob satisfaction among staff. It is estimatedthat about 70 per cent of workers exposedto racial and other discrimination take time offwork.22 A separate estimate indicates that theaverage cost of an organisation respondingto a discrimination grievance is about 55,000 per case.23Then there is the reputational damage thatcan be caused by racial discrimination. Inthe United States, where racial discriminationclass actions are more common, companiesincluding General Electric, Denny’s, Wal-Martand Abercrombie have experienced litigationthat has attracted intense public attentionand scrutiny.Even short of litigation, allegations of racialdiscrimination can do considerable damage toa corporate brand. For example, in 2015, LeslieMiley, the highest-ranking African-Americanengineer at Twitter, publicly quit the companyand claimed that Twitter failed to recruit anddevelop African-American talent, sharing hispersonal experiences within the company.Any damage to a corporate brand can bequickly translated into financial damage. Whenan American company has a diversity-relatedcomplaint, which then becomes publicly known,its share price tends to drop with 24 hours.24

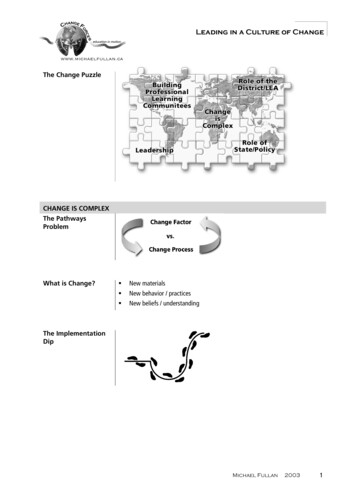

The way forwardAchieving change is never easy, but it can bedone. We believe it requires action in threeareas: leadership, systems and culture.The first seems obvious: when there is acommitment from the top of the organisation,others will follow. It is not always understood,though, that leading on cultural diversity mustinvolve ‘skin in the game’. Merely ‘getting’ theanalytical case will not be enough.Any movement must also be sustained.This requires embedding new thinking inpolicies, processes or structures. It demandsattention to the behaviours and attitudes ofemployees and management.Figure 4. Generating change on cultural diversityLeadership(commitment from senior leaders)Culture(dealing with bias andprofessional development)Systems(data and accountability)Leading for Change 11

Leadership and ‘skin in the game’Those in positions of leadership must makethe change themselves and set an examplefor others to follow.In the first place, leaders must communicatethat cultural diversity is not a matter of secondorder importance. This has been an obstacleobserved by a number of this blueprint’sauthors. Cultural diversity has been a poor,neglected cousin within the diversity family.In particular, it is sometimes assumed thataction on cultural diversity may need to wait untilorganisations complete their efforts to achievegreater gender equality. Within conversationsabout diversity and inclusion, some executiveleaders emphasise that there may not beenough ‘bandwidth’ in an organisation to handleboth gender and cultural diversity as priorities.Progress on diversity, however, is best madewhen it is even – across not only gender,but also culture, disability, age and sexualorientation. To wait until gender equality isachieved within the workplace would place theiss

Leading for Change: A blueprint for cultural diversity and inclusive leadership ISBN 978-1-921449-78-9 Acknowledgements The Working Group thanks Nick Kaldas APM, who was a member of the group until March 2016. Dr Andreea Constantin provided research assistance, with