Transcription

ISSN 2508-0865 (electronic)No. 2018-19 (December 2018)The Philippine electric powerindustry under EPIRAArlan Z.I. Brucal and Jenica A. AnchetaThe Electric Power Industry Reform Act (EPIRA) is oneof the landmark promarket reforms implemented toachieve reliable and competitively priced electricity inthe Philippines. Due to its perceived ineffectiveness,however, the law has been subjected to a number ofcriticisms with some calling for its review, if not anoutright repeal.This Policy Note revisits the achievements andconcerns regarding the implementation of EPIRA in thecountry. In particular, it enumerates the success andprogress of the law, while drawing critical reflectionsthat can be useful in drawing policy implications.Current arrangements and restructuringGenerally, EPIRA adopted the “ideal” textbookarchitecture of the competitive energy markets foundto be historically successful in Argentina, Canada,Brazil, and Australia, among others (Joskow 2005).Such adoption led to the creation of institutionalarrangements and restructuring intended to providelong-term benefits and ensure that prices reflect theefficient economic cost of supplying electricity andservice quality attributes (Joskow 2005). As shown inFigures 1 and 2, these include the following:Restructuring of the generation segmentPursuant to Section 6 of EPIRA, the generationsegment of the power sector was made competitiveand open to all qualified generation companies.Generation utilities are also no longer required tosecure franchise authority from Congress to operate. Amaximum permissible market share1 for participants inthe generation segment was also established to fostercompetition in the power generation sector.Integration of transmission facilitiesand network operationsIn 2001, the National Transmission Corporationwas created. It assumed the electrical transmissionfunction of the National Power Corporation (NPC),which used to dominate the transmission sector. Itwas also designated as the single independent systemoperator to manage the operation of the network.Prior to the EPIRA regime, this was inexistent because the share ofgeneration before was small.1

Figure 1. The electric power industry prior to the passing of the Electric Power Industry Reform ActDesign by R. ValenciaSource: Tan (2010)Separation of competitive and regulated segmentsFrom a two-sector industry, EPIRA divided theelectric power industry into four, namely, generation,transmission, distribution, and supply. Generationbecame competitive and open. The transmission anddistribution of electric power remained regulated,subject to the rate making powers of the EnergyRegulatory Commission (ERC). Meanwhile, supply ofelectricity to the contestable market was deemednot a public utility operation and suppliers were notrequired to secure national franchise. Prices chargedby the suppliers were subjected to ERC regulation.Unbundling of retail tariffsEPIRA seeks to separate prices for retail powersupplies and associated customer services that willbe supplied competitively from the regulated deliverycharges.2 The target was to have all the distributionutilities (DUs) apply for tariffs unbundling byDecember 2002. However, it was only in December2008 that almost all of the unbundling applications of120 electric cooperatives, 20 private utilities, and theNPC3 were decided by ERC.Elimination of cross-subsidiesIn 2002 and 2005, the intergrid (between Luzonand Visayas) and intragrid (within Luzon) subsidieswere removed, respectively. Meanwhile, the interclasssubsidies (between industrial and residential) wereremoved in 2005. This was done primarily to reflectthe true cost of service delivery in the power sector.Such removal of interclass subsidies was done in twophases to allow for smooth adjustment, where40 percent of the subsidies was removed in 2004 and60 percent was taken out in 2005.Refer to those relating to the use distribution and transmissionnetworks that would continue to be provided by regulated monopolies32NPC has retained some DU operations in certain areas, such as inmissionary electrification, hence is subject to unbundling as well.2 w The Philippine electric power industry under EPIRA

Figure 2. The electric power industry after the passing of the Electric Power Industry Reform ActDesign by R. ValenciaSource: Tan (2010)Contrary to the pursuit of having prices reflectthe true cost of service delivery, the governmentinstituted two distortionary pricing mechanisms,namely, (1) the lifeline rate and (2) the UniversalCharge for Missionary Electrification (UCME).Both of these mechanisms are meant to supportunderprivileged consumers’ additional charges paid byall other consumers.Pursuant to Section 73 of EPIRA on lifeline pricingscheme, residential consumers in the higherconsumption bracket would have to pay extra costas subsidy to their poorer counterparts. In 2011,Republic Act 10150 was signed, extending theimplementation of the lifeline rate for another 10years, which was supposed to be phased out in10 years upon the implementation of the EPIRA.Meanwhile, the missionary electrification is heavilysubsidized through UCME, which was financedprimarily through extra costs incurred by all otherend users.Creation of an independent regulatory bodyand a body to oversee implementation of the lawPursuant to Section 38 of the EPIRA, the ERCwas created as an independent, quasi-judicial,and regulatory body that promotes competition,encourages market development, ensures customerchoice, and penalizes abuse of market power.EPIRA also created the Joint Congressional PowerCommission (JCPC) tasked to oversee the properimplementation of the law. For example, the plan ofthe Power Sector Assets and Liabilities ManagementCorporation to privatize NPC assets is subject toendorsement of the JCPC before it is approved by thepresident of the Philippines.Creation of a wholesale electricity spot marketfor energy tradingSection 30 of the EPIRA provides for the creationof the Wholesale Electricity Spot Market (WESM) bywhich competitive market forces would establishgeneration tariffs and make costs more transparent.PIDS Policy Notes 2018-19 w 3

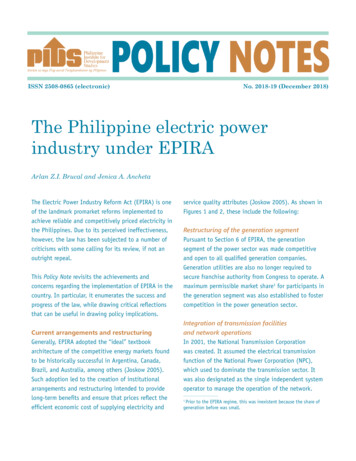

WESM commenced commercial operations in the Luzongrid in June 2006. The Visayas grid was integratedinto WESM and commenced commercial operationsin December 2010. WESM for Mindanao has not yetestablished to date, although discussions are ongoing.Implementation of retail competitionand open accessThe pinnacle of EPIRA is the full implementation ofthe Retail Competition and Open Access (RCOA)—the landmark policy designed to give consumers theoption to choose their own supplier of electricity.In 2012, or 11 years after the passing of EPIRA, ERCcommenced RCOA. Nonetheless, there were legalissues raised in relation to its implementation, oneof which is the requirement for certain consumers toparticipate in RCOA. To address legal issues raisedin 2017, which hampered the full implementationof RCOA, the Department of Energy (DOE) issuedtwo circulars that allowed qualified consumers tovoluntarily choose their suppliers instead of beingmandated to switch from their DUs to a retailelectricity supplier.Achievements under EPIRAThe reforms resulted in significant improvements in thePhilippine electric industry, which include the following:Improved reliability, quality, and affordabilityof electric supplySince the passage of EPIRA, the supply of electricityhas been adequate to ensure consumers’ continuousaccess to electricity (DOE 2017). The proportion ofhouseholds experiencing power outages has alsodropped dramatically (NSO 1995, 2004). Moreover,the country has seen a generally declining electricprice in real terms after the passing of EPIRA (Meralco2015). In 2015 alone, said price declined by 8.38percent relative to its 2000 level (Meralco 2015).In general, while the power rates in the post-EPIRAregime are still higher relative to their levels beforeEPIRA was implemented, the rate at which theseprices increases is much lower in the post-EPIRAregime. The real electricity prices have also divergedacross customers starting in 2001, driven by theremoval of cross-customer subsidies (Figure 3), whichis in line with the pursuit to have prices reflectingthe true cost of service delivery in the power sector.Commercial and industrial prices also posted a declineof 11.07 and 21.75 percent, respectively, relativeto their 2000 level. In contrast, residential pricesincreased by 3.87 percent during the 2000–2015period, although their growth rate is significantlylower compared to its 1990–2000 rate.Increased number of electrified householdsBefore EPIRA, only 76 percent of families had accessto electricity (NSO 2000). The figure went up to91.1 percent in 2015, up by 15 percentage points(PSA 2015).Improved efficiency both in the generationand transmission sectorUsing the data from National ElectrificationAdministration (2018), this study noted a negativecorrelation between average power cost and loadfactors4 for all electric cooperatives, suggesting thatan optimal structure of resource mix is in place.5Meanwhile, the situation is different in Mindanao,where the government continues to be the dominantplayer in the generation sector.Electrical load factor is a measure of the utilization rate or efficiencyof electrical energy usage. It is the ratio of total energy used in thebilling period divided by the possible total energy used within theperiod, if used at the peak demand during the entire period.5To attain least costs of service delivery, plants that are cheap to runwill be used more consistently while those that have high variablecosts will be used to meet peaks in the demand. Thus, it is optimalthat retailers with higher load factors should be able to form lowercost portfolios.44 w The Philippine electric power industry under EPIRA

Figure 2: Electricity prices for different customers of Manila Electric Company between 1990and 2015, in 2000 prices.Commented [RGV1]: We have not even discuconcept yet.Figure 3. Electricity prices for different customers of Manila Electric Company betweenin 2000 pricesCommented [B2R1]: We did (see text above)Start ofEPIRA regime6In PHP/KwHHow is this relevant in our discussion? Pls cite ththe text, else this may be removed during the laPN. and 20102015Source: Manila Electric Company (2015) (nominal electricity price); Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (2015) (consumer price index)Moreover, the transmission and distribution losseshave significantly declined since 2005 (WB 2018).Specifically, their share to total power outputdeclined, from 17 percent in 1995 to 9 percent in2014 (WB 2018). Despite this declining trend, thePhilippines still ranks among select Asian countrieswith the highest transmission and distribution losses,placing third in 2014 (WB 2018). This implies thatinvestments in transmission and distribution systemsare still warranted.Improved fiscal conditionUnder EPIRA, the country’s power industry hastransformed from a fiscally dependent industry to a nettax payer, which reduced high levels of debt that hadbeen incurred by the government prior to the reform(ADB 2016). Interestingly, looking at the data fromthe Department of Finance reveals that the countryhad budget surplus in 2006, coinciding with the initialoperation of WESM (DOF 2016). This budget surplushas remained positive, except during the 2009 globalrecession, whose impact was felt even up to 2012.Lessons and challenges under EPIRAWhile the power sector has progressed under EPIRA,this is not to say that everything worked perfectly.For instance, Joskow (2005) warned of the potentialrisk that may emerge when the energy sector reformis done incompletely or incorrectly. In the caseof the implementation of EPIRA, this includes theincomplete elimination of the cross-subsidization.Consequently, the associated costs of this policy arecurrently being shouldered by the ratepayers in theform of universal charges. As such, it would be veryuseful to determine how this policy is being valued atthe locality to assess whether the current efforts toboost electrification increase or reduce social welfare(Lee et al. 2018).EPIRA also missed some of its major targets. Thisincludes the delayed creation of a competitiveretail sector under RCOA. At present, the mandatorymigration of large electric consumers to RCOA ishalted by a temporary restraining order issued by theSupreme Court. This signals uncertainties and thePIDS Policy Notes 2018-19 w 5

The Electric Power Industry Reform Act (EPIRA) is one of the landmark promarket reforms implemented to achieve reliable andcompetitively priced electricity in the Philippines. Since the passage of EPIRA, this study found that the supply of electricity hasbeen adequate to ensure consumers’ continuous access to electricity. The country has also seen a generally declining electric pricethroughout its implementation. (Photo: Nayuki/Flickr)lack of commitment on the part of the governmentto implement its agenda of having a competitivepower sector. This can have far-reaching implicationsparticularly on the pursuit to secure adequate privatesector-led investments in the energy sector.The Philippine power sector can also push for strongerpolitical commitment to the reform. Any increase incompetition is anchored on how effective a sectorcan attract additional players. This will ensure thatno huge markups of the incumbent can be maintainedin the long run. However, the long-run tendency ofthe market to have more competition in the marketis hampered by the uncertainties brought about bysudden interventions of the government. A case inpoint is when ERC imposed a cap of PHP 62/kWh in2013 as a result of a price spike in the WESM. Felder(2007) warned that such immediate response toreduce prices through sudden regulatory mandates canundercut price signals, which later on can get worseand result in a vicious cycle of regulatory uncertainty,unfriendly investment climate, and counterproductive6 w The Philippine electric power industry under EPIRA

policies. Clearly, the government needs to firstdetermine the consequences of such intervention andassess if the perceived benefits outweigh the costs tothe entire industry.RecommendationsThus far, two major findings stood out. First, theEPIRA appears to be a well-thought power sectorreform design, having followed most of the features ofthe kind of reform structuring found to be successfulhistorically (Joskow 2005). Second, significantprogress has been attained, although a number ofmeasures should be in place to sustain the progressand promote more competitive power supply andretail rates for all consumers. In 2014, the Task Forceto Study Ways to Reduce the Price of Electricity haspublished its recommendations, which this studyreviewed and supports in line with the findings ofthe assessment. Nonetheless, other recommendationsinclude the following:GenerationDOE needs to undertake generation mapping, as apolicy and regular practice, and implement optimaldecisionmaking on the location of the generationplants. It should likewise develop a sustainableand optimal energy mix policy and demand-sidemanagement practices, such as dynamic pricingor the provision of economic nudges that seek tolower peak consumption. An initiative to developan optimization model that has both supply- anddemand-side measures, e.g., incorporating lowcost yet intermittent renewable power sourcewhile shifting peak demand where power cost islesser through dynamic pricing, is being discussedbetween the University of the Philippines College ofEngineering and the University of Hawaii. Results ofthis initiative should inform the DOE in carving outwhat the optimal investment portfolio in the sector.Transmission and system operationThe National Grid Corporation of the Philippines mustundertake capital expenditures to further strengthentransmission, and even distribution, systems;resolve transmission congestions; and modernize theinfrastructure. Modernizing the grid can incorporatemore renewables, which, at the pace of theirwholesale price relative to that of fossil fuel, can bemore competitive in the future.DistributionDUs must continue improving the generation mix atthe DU level, particularly in Mindanao. On the samehand, ERC must streamline and fast-track the approvalof power supply agreements to encourage moreinvestments in the sector. This may entail buildingadditional capacities and government funding toperform the task.System lossesWith the help from the industry players and academicinstitutions, DOE must carefully examine thecomponents of the systems loss, with the view toidentify ways of reducing them. Consequently, thisexercise may lead to a review of the ERC-set cap onsystems losses. ERC must also strictly enforce AntiElectricity Pilferage Law and aim for a long-term goalof single-digit losses.Universal chargesWith the help from the industry players andacademic institutions, DOE must also review the costeffectiveness of the universal charges and determineways of attaining the same objective with lessdistortions in the power sector. Meanwhile, NPC mustimprove the missionary electrification implementationto reduce these charges. NPC can partner with theprivate sector and academic entities to evaluatethe cost effectiveness of missionary electrification.Moreover, the group can look into the prospect of thePIDS Policy Notes 2018-19 w 7

national government absorbing universal charges andhow they influence overall welfare.TaxesDOE must review whether or not the governmentis overtaxing the energy sector. This may includereviewing the legislations on taxes on electric powerand whether or not these can be gradually reduced orphased out.Demand managementLastly, DOE must develop and implement demand-sidemeasures (e.g., dynamic pricing). This may entailconducting an analysis of the potential of thesemeasures and opportunities that the countrycan exploit. 4ReferencesAsian Development Bank (ADB). 2016. Philippines:Electricity Market and Transmission DevelopmentProject. ADB Evaluation Report. Mandaluyong City,Philippines: ADB.Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP). 2015. Consumer priceindex. Manila, Philippines: BSP. http://www.bsp.gov.ph/statistics/efs prices.asp (accessed on November26, 2018).Department of Finance (DOF). 2016. National governmentbudget. Manila, Philippines: DOF. https://www.dof.gov.ph/index.php/statistics bulletin/ng-budget/(accessed on November 26, 2018).Department of Energy (DOE). 2017. DOE power statistics.Taguig City, Philippines: DOE. https://www.doe.gov.ph/philippine-power-statistics (accessed on November26, 2018).Felder, F. 2007. Electricity market reform: An internationalperspective. The Energy Journal 28(1):173–175.Joskow, P.L. 2005. Regulation and deregulation after25 years: Lessons for research. Review of industrialOrganization 26:169–193.Lee, K., E. Miguel, and C. Wolfram. 2018. Experimentalevidence on the economics of rural electrification.Working Paper.Cambridge, MA: National Bureau ofEconomic Research, Inc. 2274768/repp-jpe 2018-0131-final.pdf (accessed on November 26, 2018).Manila Electric Company (Meralco). 2015. Nominalelectricity price. Pasig City, Philippines: visories/rates-archives (accessed on November 26, 2018).National Electrification Administration (NEA). 2018.Average peak load and average system rates of electriccooperatives. Quezon City, Philippines: NEA.National Statistics Office (NSO). 1995. Household energyconsumption survey. Manila, Philippines: NSO.———. 2000. 2000 Family Income and Expenditure Survey.Manila, Philippines: NSO.———. 2004. Household energy consumption survey.Manila, Philippines: NSO.Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA). 2015. 2015Family Income and Expenditure Survey. Quezon City,Philippines: PSA.Tan, R.A. (2010). Regulating Towards A Brighter Future[Powerpoint Presentation]. Pasig City, Philippines: EnergyRegulatory Commission. 12.30%203Rauf%20A.%20Tan(Philippines).pdf. (accessed on November 26, 2018)Task Force to Study Ways to Reduce the Price of Electricity.2014. Final report of the Task Force to Study Waysto Reduce the Price of Electricity: Findings andrecommendations. Taguig City, Philippines: Departmentof Energy.World Bank (WB). 2018. World Development Indicators.Washington, D.C.: WB.Contact usAddress:Telephone:Email:Website:Research Information DepartmentPhilippine Institute for Development Studies18/F Three Cyberpod Centris - North TowerEDSA corner Quezon Avenue, Quezon City( 63-2) 372-1291 to 92publications@mail.pids.gov.phwww.pids.gov.phPIDS Policy Notes are analyses written by PIDS researchers on certainpolicy issues. The treatise is holistic in approach and aims to provideuseful inputs for decisionmaking.The authors are consultant and research analyst II at the PhilippineInstitute for Development Studies (PIDS). The views expressed arethose of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the PIDSor any of the study’s sponsors.8 w The Philippine electric power industry under EPIRA

electric power industry into four, namely, generation, transmission, distribution, and supply. Generation became competitive and open. The transmission and distribution of electric power remained regulated, subject to the rate making powers of the