Transcription

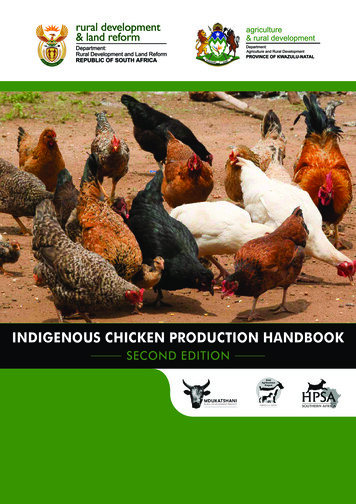

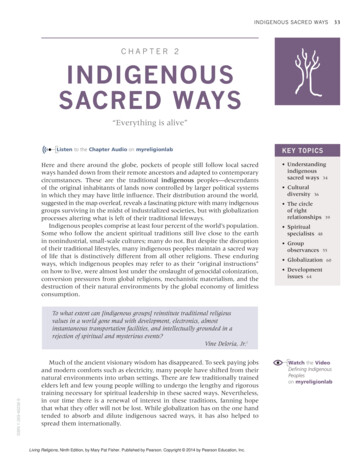

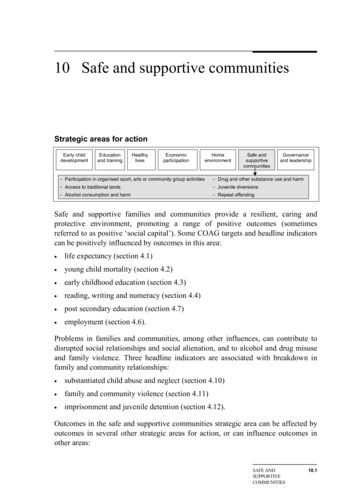

INDIGENOUS SACRED WAYSCHAPTER 2INDIGENOUSSACRED WAYS“Everything is alive”Listen to the Chapter Audio on myreligionlabHere and there around the globe, pockets of people still follow local sacredways handed down from their remote ancestors and adapted to contemporarycircumstances. These are the traditional indigenous peoples—descendantsof the original inhabitants of lands now controlled by larger political systemsin which they may have little influence. Their distribution around the world,suggested in the map overleaf, reveals a fascinating picture with many indigenousgroups surviving in the midst of industrialized societies, but with globalizationprocesses altering what is left of their traditional lifeways.Indigenous peoples comprise at least four percent of the world’s population.Some who follow the ancient spiritual traditions still live close to the earthin nonindustrial, small-scale cultures; many do not. But despite the disruptionof their traditional lifestyles, many indigenous peoples maintain a sacred wayof life that is distinctively different from all other religions. These enduringways, which indigenous peoples may refer to as their “original instructions”on how to live, were almost lost under the onslaught of genocidal colonization,conversion pressures from global religions, mechanistic materialism, and thedestruction of their natural environments by the global economy of limitlessconsumption.KEY TOPICS Understandingindigenoussacred ways 34 Culturaldiversity36 The circleof rightrelationships Spiritualspecialists3948 Groupobservances55 Globalization60 Developmentissues 64ISBN 1-269-46236-9To what extent can [indigenous groups] reinstitute traditional religiousvalues in a world gone mad with development, electronics, almostinstantaneous transportation facilities, and intellectually grounded in arejection of spiritual and mysterious events?Vine Deloria, Jr.1Much of the ancient visionary wisdom has disappeared. To seek paying jobsand modern comforts such as electricity, many people have shifted from theirnatural environments into urban settings. There are few traditionally trainedelders left and few young people willing to undergo the lengthy and rigoroustraining necessary for spiritual leadership in these sacred ways. Nevertheless,in our time there is a renewal of interest in these traditions, fanning hopethat what they offer will not be lost. While globalization has on the one handtended to absorb and dilute indigenous sacred ways, it has also helped tospread them internationally.Living Religions, Ninth Edition, by Mary Pat Fisher. Published by Pearson. Copyright 2014 by Pearson Education, Inc.Watch the VideoDefining IndigenousPeopleson myreligionlab33

34 INDIGENOUS SACRED WAYSUnderstanding indigenous sacred waysOutsiders have known or understood little of the indigenous sacred ways,many of which have long been practiced only in secret. In Mesoamerica, theancient teachings have remained hidden for 500 years since the coming ofthe conquistadores, passed down within families as a secret oral tradition.The Buryats living near Lake Baikal in Russia were thought to have beenconverted to Buddhism and Christianity centuries ago; however, almost theentire population of the area gathered for indigenous ceremonies on OlkhonIsland in 1992 and 1993.In parts of aboriginal Australia, the indigenous teachings have been underground for 200 years since white colonialists and Christian missionariesappeared. As aborigine Lorraine Mafi Williams explains:We have stacked away our religious, spiritual, cultural beliefs. When themissionaries came, we were told by our old people to be respectful, listen andbe obedient, go to church, go to Sunday school, but do not adopt the Christiandoctrine because it takes away our cultural, spiritual beliefs. So we’ve alwaysstayed within God’s laws in what we know.2Not uncommonly, the newer global traditions have been blended withthe older ways. For instance, Buddhism as it spread often adopted existingcustoms, such as the recognition of local deities. Now many indigenous peoplepractice one of the global religions while still retaining many of their traditional ways.Until recently, those who attempted to ferret out the native sacred wayshad little basis for understanding them. Many were anthropologists whoapproached spiritual behaviors from the nonspiritual perspective of WesternThe approximatedistribution ofindigenous groupsmentioned inthis chapter.Saami(Lapp)Yup ikYurokNezPerceHaidaInuit(Eskimo)Koyu konDene lagi MayagaraKhasiDaNavajoPapagoBakongoAkan YorubaEfeKikuyuOrang AsliAchewaVadumaKungMaoriLiving Religions, Ninth Edition, by Mary Pat Fisher. Published by Pearson. Copyright 2014 by Pearson Education, Inc.ISBN 1-269-46236-9Australianaborigines

INDIGENOUS SACRED WAYSscience or else the Christian understanding of religion as a means of salvationfrom sinful earthly existence—a belief not found among most indigenouspeoples. There is a great difference beween the conceptual frameworks ofAfrican traditional religions and the thinking of Western scholars. Knowingthat researchers from other cultures did not grasp the truth of their beliefs,native peoples have at times given them information that was incorrect inorder to protect the sanctity of their practices from the uninitiated.Academic study of traditional ways is now becoming more sympathetic andself-critical, however, as is apparent in this statement by Gerhardus CorneliusOosthuizen, a European researching African traditional religions:[The] Western worldview is closed, essentially complete and unchangeable,basically substantive and fundamentally non-mysterious; i.e. it is like a rigidprogrammed machine. This closed worldview is foreign to Africa, whichis still deeply religious. This world is not closed, and not merely basicallysubstantive, but it has great depth, it is unlimited in its qualitative varieties andis truly mysterious; this world is restless, a living and growing organism.3ISBN 1-269-46236-9Indigenous spirituality is a lifeway, a particular approach to all of life.It is not a separate experience, like meditating in the morning or going tochurch on Sunday. Many indigenous languages have no word for “religion.”Rather, spirituality ideally pervades all moments. There is no sharp dichotomybetween sacred and secular domains. As an elder of the Huichol in Mexicoputs it:Everything we do in life is for the glory of God. We praise him in the wellswept floor, the well-weeded field, the polished machete, the brilliant colors ofthe picture and embroidery. In these ways we prepare for a long life and prayfor a good one.4Living Religions, Ninth Edition, by Mary Pat Fisher. Published by Pearson. Copyright 2014 by Pearson Education, Inc.Uluru (Ayers Rock), aunique mass rising fromthe plains of centralAustralia, has long beenconsidered sacred by theaboriginal groups of thearea, and in its caves aremany ancient paintings.35

36 INDIGENOUS SACRED WAYSRead the DocumentThe Theft of Lighton myreligionlabIn most native cultures, spiritual lifeways are shared orally. There are noscriptures of the sort that other religions are built around (although somewritten texts, such as the Mayan codices, were destroyed by conqueringgroups). Instead, the people create and pass on songs, proverbs, myths,riddles, short sayings, legends, art, music, and the like. This helps to keepthe indigenous sacred ways dynamic and flexible rather than fossilized.It also keeps the sacred experience fresh in the present. Oral narratives mayalso contain clues to the historical experiences of individuals or groups,but these are often carried from generation to generation in symboliclanguage. The symbols, metaphors, and humor are not easily understoodby outsiders but are central to a people’s understanding of how life works.To the Maori of New Zealand, life is a continual dynamic process of becoming in which all things arise from a burst of cosmic energy. According totheir creation story, all beings emerged from a spatially confined liminalstate of darkness in which the Sky Father and Earth Mother were lockedin eternal embrace, continually conceiving but crowding their offspringuntil their children broke that embrace. Their separation created a greatburst of light, like wind sweeping through the cosmos. That tremendouslyfreeing, rejuvenating power is still present and can be called upon throughrituals in which all beings—plants, trees, fish, birds, animals, people—areintimately and primordially related.The lifeways of many small-scale cultures are tied to the land on whichthey live and their entire way of life. They are most meaningful within thiscontext. Many traditional cultures have been dispersed or dismembered, asin the forced emigration of slaves from Africa to the Americas. Despite this,the dynamism of traditional religions has made it possible for African spiritualways to transcend space, with webs of relationships still maintained betweenthe ancestors, spirits, and people in the diaspora, though they may be practiced secretly and are little understood by outsiders.Despite the hindrances to understanding of indigenous forms of spirituality, the doors to understanding are opening somewhat in our times. Firstly,the traditional elders are very concerned about the growing potential forplanetary disaster. Some are beginning to share their basic values, if not theiresoteric practices, in hopes of preventing industrial societies from destroyingthe earth.Cultural diversityLiving Religions, Ninth Edition, by Mary Pat Fisher. Published by Pearson. Copyright 2014 by Pearson Education, Inc.ISBN 1-269-46236-9In this chapter we are considering the faithways of indigenous peoples as awhole. However, behind these generalizations lie many differences in socialcontexts, as well as in religious beliefs and practices. Some contemporaryscholars even question whether “indigenous” is a legitimate category in thestudy of religions, for they see it as a catchall “other” category consisting ofvaried sacred ways that do not fit within any of the other major global categories of organized religions.To be sure, there are hundreds of different indigenous traditions in NorthAmerica alone, and at least fifty-three different ethnolinguistic groups inthe Andean rainforests. And Australian aboriginal lifeways, which are someof the world’s oldest surviving cultures, traditionally included over 500 different clan groups, with differing beliefs, living patterns, and languages.Indigenous traditions have evolved within materially as well as religiously

INDIGENOUS SACRED WAYS37diverse cultures. Some are descendants of civilizations with advanced urbantechnologies that supported concentrated populations. When the Spanishconqueror Cortés took over Tenochtitlán (which now lies beneath MexicoCity) in 1519, he found it a beautiful clean city with elaborate architecture,indoor plumbing, an accurate calendar, and advanced systems of mathematicsand astronomy. Former African kingdoms were highly culturally advancedwith elaborate arts, such as intricate bronze and copper casting, ivory carving, goldworking, and ceramics. In recent times, some Native American tribeshave become quite materially successful via economic enterprises, such asgambling complexes.Among Africa’s innumerable ethnic and social groupings, there are someindigenous groups comprising millions of people, such as the Yoruba. At theother extreme are those few small-scale cultures that still maintain a survivalstrategy of hunting and gathering. For example, some Australian aboriginescontinue to live as mobile foragers, though restricted to government-ownedstations. A nomadic survival strategy necessitates simplicity in material goods;whatever can be gathered or built rather easily at the next camp need not bedragged along. But material simplicity is not a sign of spiritual poverty. TheAustralian aborigines have complex cosmogonies, or models of the origins ofthe universe and their purpose within it, as well as a working knowledge oftheir own bioregion.Some traditional peoples live in their ancestral enclaves, though notuntouched by the outer world. The Hopi people have continuously occupieda high plateau area of the southwestern United States for between 800 and1,000 years; their sacred ritual calendar is tied to the yearly farming cycle.Tribal peoples have lived deep in the forests and hills of India for thousandsof years, utilizing trees and plants for their food and medicines, although sincethe twentieth century their ancestral lands have been taken over for “development” projects and encroached upon by more politically and economicallypowerful groups, rendering many of the seventy-five million Indian tribespeople landless laborers.ISBN 1-269-46236-9The indigenous communityof Acoma Pueblo—builton a high plateau in NewMexico—may live in theoldest continuously occupiedcity in the United States.Living Religions, Ninth Edition, by Mary Pat Fisher. Published by Pearson. Copyright 2014 by Pearson Education, Inc.

38 INDIGENOUS SACRED WAYSAustralian aboriginesunderstand theirenvironment as concentricfields of subtle energies.(Nym Bunduk, 1907–1974,Snakes and Emu.)Living Religions, Ninth Edition, by Mary Pat Fisher. Published by Pearson. Copyright 2014 by Pearson Education, Inc.ISBN 1-269-46236-9Listen to the PodcastLiving Vodouon myreligionlabOther indigenous peoples visit their sacred sites and ancestral shrines butlive in more urban settings because of job opportunities. The people who participate in ceremonies in the Mexican countryside include subway personnel,journalists, and artists of native blood who live in Mexico City.In addition to variations in lifestyles, indigenous traditions vary in theiradaptations to dominant religions. Often native practices have becomeinterwoven with those of global religions, such as Buddhism, Islam, andChristianity. In Southeast Asia, household Buddhist shrines are almost identical to the spirit houses in which the people still make offerings to honorthe local spirits. In Africa, the spread of Islam and Christianity saw the introduction of new religious ideas and practices into indigenous sacred ways.The encounter transformed indigenous religious thought and practice butdid not supplant it; indigenous religions preserved some of their beliefsand ritual practices but also adjusted to the new sociocultural milieu. TheDahomey tradition from West Africa was carried to Haiti by African slavesand called Vodou, from vodu, one of the names for the chief nonhumanspirits. Forced by European colonialists to adopt Christianity, worshippers ofVodou secretly fused their old gods with their images of Catholic saints. Morerecently, emigrants from Haiti have formed diaspora communities of Vodouworshipers in cities such as New York, New Orleans, Miami, and Montreal,where Vodou specialists are often called upon to heal sickness and use magicto bring desired changes.

INDIGENOUS SACRED WAYS39Despite their different histories and economic patterns, and their geographical separation, indigenous sacred ways have some characteristics in common.Perhaps from ancient contact across land-bridges that no longer exist, thereare similarities between the languages of the Tsalagi in the Americas, Tibetans,and the aboriginal Ainu of Japan. Similarities found among the myths of geographically separate peoples can be accounted for by global diffusion throughtrade, travel, communications, and other kinds of contact, and by parallel origin because of basic similarities in human experience, such as birth and death,pleasure and pain, and wonderment about the cosmos and our place in it.Certain symbols and metaphors are repeated in the inspirational art andstories of many traditional cultures around the world, but the people’s relationships to, and the concepts surrounding, these symbols are not inevitablythe same. Nevertheless, the following sections look at some recurring themesin the spiritual ways of diverse indigenous cultures.The circle of right relationshipsFor many indigenous peoples, everything in the cosmos is intimately interrelated. These interrelationships originate in the way everything was created.To Australian aborigines, before time began there was land, but it was flat anddevoid of any features. Powerful ancestral beings came forth from beneaththe surface and began moving around, shaping the land as they moved acrossit. In this Dreamtime, the ancestral figures also created groups of humans totake care of the places that had been created. The people thus feel that theybelong to their native place in an eternal sacred relationship.A symbol of unity among the parts of this sacred reality is a circle. This isnot used by all indigenous people; the Navajo, for instance, regard a completed circle as stifling and restrictive. However, many other indigenous peopleshold the circle sacred because it is infinite—it has no beginning, no end. Timeis circular rather than linear, for it keeps coming back to the same place. LifeISBN 1-269-46236-9Among the gentle Efepygmies of the Ituri Forestin the Democratic Republicof Congo (formerly Zaire),children learn to value thecircle by playing the “circlegame.” With feet making acircle, each child names acircular object and then anexpression of roundness (thefamily circle, togetherness,“a complete rainbow”).Living Religions, Ninth Edition, by Mary Pat Fisher. Published by Pearson. Copyright 2014 by Pearson Education, Inc.

40 INDIGENOUS SACRED WAYSrevolves around the generational cycles of birth, youth, maturity, and physicaldeath, the return of the seasons, the cyclical movements of the moon, sun,stars, and planets. Rituals such as rites of passage may be performed to helpkeep these cycles in balance.To maintain the natural balance of the circles of existence, most indigenouspeoples have traditionally been taught that they must develop right relationships with everything that is. Their relatives include the unseen world ofspirits, the land and weather, the people and creatures, and the power within.Relationships with spiritDeity may be conceived aseither male or female inindigenous religions. InNavajo belief, divinity ispersonified as both FatherSky and Mother Earth.In this traditional sandpainting, Father Sky is onthe left, with constellationsand the Milky Way forminghis “body.” Mother Earthis on the right, with herbody bearing the four sacredplants: squash, beans,tobacco, and corn.The cosmos is thought to contain and be affected by numerous divinities,spirits, and also ancestors. Many indigenous traditions worship a SupremeBeing who they believe created the cosmos. This being is known by theLakota as “Great Mysterious” or “Great Spirit.” African names for the beingare attributes, such as “All-powerful,” “Creator,” “the one who is met everywhere,” “the one who exists by himself,” or “the one who began the forest.”The Supreme Being is often referred to by male pronouns, but in some groupsthe Supreme Being is a female. Some tribes of the southwestern United Statescall her “Changing Woman”—sometimes young, sometimes old, the motherof the earth, associated with women’s reproductive cycles and the mysteryof birth, the creatrix. Many traditional languages make no distinction betweenmale and female pronouns, and some see the divine as androgynous, a forcearising from the interaction of male and female aspects of the universe.In African traditional religions, the Supreme Being—whether singular orplural—may have humanlike qualities, but no gender. This great Source isso awesome that no images are used torepresent it.Awareness of one’s relationship to theGreat Power is thought to be essential, butthe power itself remains unseen and mysterious. An Inuit spiritual adept describedhis people’s experience of:To traditional Buryats of Russia, thechief power in the world is the eternallyblue sky, Tengry. African myths suggestthat the High God was originally so closeLiving Religions, Ninth Edition, by Mary Pat Fisher. Published by Pearson. Copyright 2014 by Pearson Education, Inc.ISBN 1-269-46236-9a power that we call Sila, which is not to beexplained in simple words. A great spirit,supporting the world and the weather andall life on earth, a spirit so mighty that[what it says] to mankind is not throughcommon words, but by storm and snowand rain and the fury of the sea; all theforces of nature that men fear. But Silahas also another way of [communicating];by sunlight and calm of the sea, and littlechildren innocently at play, themselvesunderstanding nothing. When all iswell, Sila sends no message to mankind, butwithdraws into endless nothingness, apart.5

INDIGENOUS SACRED WAYSto humans that they became disrespectful. The All-powerful was like the sky,they say, which was once so close that children wiped their dirty hands onit, and women (blamed by men for the withdrawal) broke off pieces for soupand bumped it with their sticks when pounding grain. Although southernand central Africans believe in a high being who presides over the universe,including less powerful spirits, they consider this being either too distant, toopowerful, or too dangerous to worship or call on for help.It cannot therefore be said that indigenous concepts of, and attitudestoward, a Supreme Being are necessarily the same as that which Westernmonotheistic religions refer to as God or Allah. In African traditional religions,much more emphasis tends to be placed on the transcendent dimensionsof everyday life and doing what is spiritually necessary to keep life goingnormally. Many unseen powers are perceived to be at work in the materialworld. In various traditions, some of these are perceived without form, asmysterious presences, who may be benevolent or malevolent. Others areperceived as having more definite, albeit invisible, forms and personalities.These may include deities with human-like personalities, the nature spiritsof special local places, such as venerable trees and mountains, animal spirithelpers, personified elemental forces, ancestors who still take an interest intheir living relatives, or the nagas, known to the traditional peoples of Nepalas invisible serpentine spirits who control the circulation of water in the worldand also within our bodies.Ancestors may be extremely important. Traditional Africans understandthat the person is not an individual, but a composite of many souls—thespirits of one’s parents and ancestors—resonating to their feelings. Rev.William Kingsley Opoku, International Coordinator of the African Council forSpiritual Churches, says:ISBN 1-269-46236-9Our ancestors are our saints. Christian missionaries who came here wanted usto pray to their saints, their dead people. But what about our saints? If youare grateful to your ancestors, then you have blessings from your grandmother,your grandfather, who brought you forth.6Continued communication with the “living dead” (ancestors who have diedwithin living memory) is extremely important to some traditional Africans.In libation rituals, food and drink are offered to the ancestors, acknowledgingthat they are still in a sense living and engaged with the people’s lives. Failureto keep in touch with the ancestors is a dangerous oversight, which may bringmisfortunes to the family.The Dagara of Burkina Faso in West Africa are familiar with the kontombili,who look like humans but are only about one foot (thirty centimeters) tall,because of the humble way they express their spiritual power. Other WestAfrican groups, descendants of ancient hierarchical civilizations, recognizea great pantheon of deities, the orisa or vodu, each the object of special cultworship. The orisa are embodiments of the dynamic forces in life, such asOya, powerful goddess of change, experienced in winds; Osun, orisa of freshwaters, associated with sweetness, healing, love, fertility, and prosperity;Olokun, ruler of the mysterious depths of consciousness; Shango, a formerking who is now honored as the stormy god of electricity and genius; Ifa,god of wisdom; and Obatala, the source of creativity, warmth, and enlightenment. At the beginning of time, in Yoruba cosmology, there was onlyone godhead, described by psychologist Clyde Ford as “a beingless being, adimensionless point, an infinite container of everything, including itself.”7Living Religions, Ninth Edition, by Mary Pat Fisher. Published by Pearson. Copyright 2014 by Pearson Education, Inc.41

42 INDIGENOUS SACRED WAYSYORUBA TEACHING STORYOsun and the Power of WomanOlodumare, the Supreme Creator, who is both femaleand male, wanted to prepare the earth for humanhabitation. To organize things, Olodumare sent theseventeen major deities. Osun was the only woman;all the rest were men. Each of the deities was givenspecific abilities and specific assignments. But whenthe male deities held their planning meetings, theydid not invite Osun. “She is a woman,” they said.However, Olodumare had given great powersto Osun. Her womb is the matrix of all life in theuniverse. In her lie tremendous power, unlimitedpotential, infinities of existence. She wears aperfectly carved, beaded crown, and with her beadedcomb she parts the pathway of both human anddivine life. She is the leader of the aje, the powerfulbeings and forces in the world.When the male deities ignored Osun, shemade their plans fail. The male deities returned toOlodumare for help. After listening, Olodumareasked, “What about Osun?” “She is only a woman,”they replied, “so we left her out.” Olodumare spokein strong words, “You must go back to her, beg herfor forgiveness, make a sacrifice to her, and give herwhatever she asks.”The male deities did as they were told, and Osunforgave them. What did she ask for in return? Thesecret initiation that the men used to keep womenin the background. She wanted it for herself and forall women who are as powerful as she is. The menagreed and initiated her into the secret knowledge.From that time onward, their plans were successful.8According to the mythology, this being was smashed by a boulder pusheddown by a rebellious slave, and broke into hundreds of fragments, each ofwhich became an orisa. According to some analysts, orisa can also be seenas archetypes of traits existing within the human psyche. Their ultimatepurpose—and that of those who pay attention to them as inner forces—is toreturn to that presumed original state of wholeness.The spirits are thought to be available to those who seek them as helpers,as intermediaries between the people and the power, and as teachers. A rightrelationship with these spirit beings can be a sacred partnership. Seekersrespect and learn from them; they also purify themselves in order to engagetheir services for the good of the people. As we will later see, those who areconsidered most able to call on the spirits for help are the shamans who havededicated their lives to this service.Teachings about the spirits also help the people to understand howthey should live together in society. Professor Deidre Badejo observes thatin Yoruba tradition there is an ideal of balance between the creativity ofwomen who give and sustain life, and the power of men who protect life.Under various internal and external pressures, this balance has swungtoward male dominance, but the stories of feminine power (see Box) andthe necessity for men to recognize it remain in the culture, teaching an idealsymmetry between female and male roles. In many indigenous cultures,women appear as powerful beings in myths and they are thought to havegreat ritual power.In addition to the unseen powers, all aspects of the tangible world are believedto be imbued with spirit. Josiah Young III explains that in African traditionalreligion, both the visible and invisible realms are filled with spiritual forces:Living Religions, Ninth Edition, by Mary Pat Fisher. Published by Pearson. Copyright 2014 by Pearson Education, Inc.ISBN 1-269-46236-9Kinship with all creation

INDIGENOUS SACRED WAYS43The visible is the natural and cultural environment, of which humans, alwaysin the process of transformation, are at the center. The invisible connotes thenuminous field of ancestors, spirits, divinities, and the Supreme Being, all ofwhom, in varying degrees, permeate the visible. Visible things, however, are notalways what they seem. Pools, rocks, flora, and fauna may dissimulate invisibleforces of which only the initiated are conscious.9Within the spiritually charged visible world, all things may be understoodas spiritually interconnected. Everything is therefore experienced as family. InAfrican traditional lifeways, “we” may be more important than “I,” and this“we” often refers to a large extended family and ancestral village, even forpeople who have moved to the cities. In indigenous cultures, the communityis paramount, and it may extend beyond the living humans in the area. Manytraditional peoples know the earth as their mother. The land one lives on ispart of her body, loved, respected, and well known. Oren Lyons, an elder ofthe Onondaga Nation Wolf Clan, speaks of this intimate relationship:[The indigenous people’s] knowledge is profound and comes from living in oneplace for untold generations. It comes from watching the sun rise in the eastand set in the west from the same place over great sections of time. We are asfamiliar with the lands, rivers and great seas that surround us as we are withthe faces of our mothers. Indeed we call the earth Etenoha, our mother, fromwhence all life springs. We do not perceive our habitat as wild but as a placeof great security and peace, full of life.10Some striking feature of the natural environment of an area—such as agreat mountain or canyon—may be perceived as the center from which thewhole world was created. Such myths heighten the perceived sacredness ofthe land. Western Tib

CHAPTER 2 “Everything is alive” Understanding indigenous sacred ways 34 Cultural diversity 36 The circle of right relationships 39 Spiritual specialists 48 Group observances 55 Globalization 60 Development issues 64 Listen to the Chapter

![The Book of the Damned, by Charles Fort, [1919], at sacred .](/img/24/book-of-the-damned.jpg)