Transcription

VEGETARIANISM/VEGANISM: A SOCIOLOGICAL ANALYSISA ThesisbySTÉPHANIE REYMONDSubmitted to the Office of Graduate and Professional Studies ofTexas A&M Universityin partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree ofMASTER OF SCIENCEChair of Committee,Co-Chair of Committee,Committee MemberHead of Department,Edward MurguiaJoe R. FeaginWilliam Alexander McIntoshJane SellAugust 2016Major Subject: SociologyCopyright 2016 Stéphanie Reymond

ABSTRACTThe vegetarian/vegan movement, as all social movements, is impacted bysystemic issues, here, the issues of race, class, and gender. This study begins with ananalysis of the relationships between these systemic issues and vegetarianism/veganism,by means of an examination of twenty well-known vegetarians/vegans. The twenty wereselected on the basis both of their importance to the movement, and on the amount ofmaterial written about them.My findings are first, concerning race, that there was a greater number of nonHispanic Whites than Blacks, Latinos/as, or Asians among the twentyvegetarians/vegans, a finding consistent with the literature on the subject. Secondly, interms of social class, the selection of twenty vegetarians/vegans had more individualsfrom the upper-middle and lower-upper classes, than from the lower social classes.Finally, concerning gender, more men than women were included in the list of twenty.This latter finding is not consistent with the literature which indicates that more womenthan men are vegetarian/vegan, this is probably due to the fact that, generally speaking,women tend to be under-represented in the mass media.The second part of this study is a micro-analysis of the discourse of five of thetwenty vegetarians/vegans. Their motivations for becoming vegetarian/vegan arediscussed, in particular their concern for animal welfare and human health. The analysisof the five also demonstrated that their paths to becoming vegetarian/vegan rarely weredirect and that most experienced some back-and-forth movements in the process of theirii

conversions. Based on the accounts of the five, factors facilitating the conversion tovegetarianism/veganism included the importance of having a strong vegetarian/vegansocial network, of having the support of close friends and family, and the important rolethat media plays in the diffusion of the movement. On the other hand, factors keepingpeople from becoming or from staying vegetarian/vegan are presented, such as negativestereotypes about veganism, as well as the absence of the link between meat about to beeaten and the fact that this meat once was a living animal.iii

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTSI would like to express my sincere gratitude to my mentor and Committee CoChair, Professor Edward Murguia, for his continuous support, guidance, andencouragement throughout the course of this research. I am beyond grateful for the timehe spent advising me on this thesis and I could not have imagined having a better advisorand mentor for my graduate studies.I would like to thank my Committee Co-chair, Professor Joe R. Feagin, for hisguidance and insightful comments. I am grateful for his immense knowledge and for thetime he dedicated to enrich my ideas. Thank you for the words of encouragement andsupport as well.In addition, my sincere thank you goes to Professor Alex McIntosh, who gave methe freedom to explore on my own but who was always available to give me direction.iv

TABLE OF CONTENTSPageABSTRACT .iiACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .ivTABLE OF CONTENTS .vINTRODUCTION .1DEFINITION OF VEGETARIANISM/VEGANISM .3A BRIEF HISTORY OF VEGETARIANISM/VEGANISM .5The History of Vegetarianism in Europe .The History of Vegetarianism in America .Vegetarianism/Veganism Today .5710METHODS.13DEMOGRAPHIC FACTORS INFLUENCING THE CONVERSION TOVEGETARIANISM/VEGANISM .16Gender Differences Among Vegetarians/Vegans .Is Vegetarianism/Veganism Based on Social Class? .Racial Differences in Vegetarianism/Veganism .162327OTHER GENERAL DEMOGRAPHICSCONCERNING VEGETARIANS/VEGANS .30Age .Marital Status .3030FIVE ACCOUNTS OF WELL-KNOWN VEGETARIANS/VEGANS .32Paul McCartney .Kristina Carrillo-Bucaram .Ellen DeGeneres .Thierry Casasnovas .T. Colin Campbell .3333333334v

DETAILED ANALYSIS OF THE FIVE VEGETARIANS/VEGANS .35The Path to Vegetarianism/Veganism .Factors Contributing to the Diffusion or Retrenchmentof Vegetarianism/Veganism .Reasons for Becoming Vegetarian/Vegan, Based on Five Detailed Accounts .More than Just a Diet, a Spiritual Awakening.Engagement in the Vegetarian/Vegan Community .35CONCLUSION .56REFERENCES .60APPENDIX A .65vi38455153

INTRODUCTIONWe should always be clear that animal exploitation is wrong because it involvesspeciesism. And speciesism is wrong because, like racism, sexism, homophobia, antiSemitism, classism, and all other forms of human discrimination, speciesism involvesviolence inflicted on members of the moral community where that infliction ofviolence cannot be morally justified. Gary L. Francione, animal rights advocate andDistinguished Professor of Law, Rutgers School of Law-Newark.This research is a comprehensive sociological analysis of vegetarianism/veganism.In-depth studies of this movement and the dimensions I examine have been non-existent.Little is known about how and why individuals become vegetarian/vegan. My intent is togo beyond the idea of vegetarianism/veganism as being only a diet consisting of noteating and not wearing animal products. First, I will define and detail the history of thevegetarian/vegan movement. I will demonstrate that vegetarianism/veganism is a socialmovement embedded in a larger system that is sexist, racist, and classist. Socialmovements are defined as “a form of political association between persons who have atleast a minimal sense of themselves as connected to others in common purpose and whocome together across an extended period of time to effect social change in the name ofthat purpose” (James and van Seeters 2014). We will see that vegetarians/vegans,because they share a common identity and because they organize in associations for thepurpose of changing mainstream views on vegetarianism/veganism, are engaged in asocial movement. We will see that the systemic issues of race, class, and gender areinterconnected, that they impact the vegetarian/vegan movement, and that they influencethose wanting to access a vegetarian/vegan diet. To do this, I will review the literaturelinking race/class/ gender to vegetarianism/veganism.1

Next, I will compare the biographies of twenty well-known vegetarians/vegans,analyzing them to see if they fit the literature on the connections betweenvegetarianism/veganism and race, class, and gender. Thus, I will not only look atsystemic relationships, but I will look at relationships at the individual level as well.Further, I select five of the twenty accounts of vegetarians/vegans, and thoroughlyanalyze them to obtain even more information about their paths tovegetarianism/veganism and the back and forth movements they may have experiencedin their conversions. Based on these five accounts, I explore the factors contributing tothe diffusion of vegetarianism/veganism. Elements such as the importance of having avegetarian/vegan social network, having the support of close friends and family, as wellas the important role that media is playing in the diffusion of the movement will bediscussed. On the other hand, factors keeping people from becoming or from stayingvegetarian/vegan also will be examined. Negative stereotypes about veganism as well asthe disconnection between pieces of meat and living animals will be revealed throughthe analyses of the five vegetarians’/vegans’ accounts. Finally, I demonstrate again theimportance of considering the vegetarian/vegan movement as more than only a dietthrough a presentation of accounts that tells us that vegetarianism/veganism often is likea spiritual awakening.2

DEFINITION OF VEGETARIANISM/VEGANISMIt is useful here to define what vegetarianism and what veganism mean. Avegetarian has been defined by the Vegetarian Society as “someone who lives on a dietof grains, pulses1, nuts, seeds, vegetables and fruits with, or without, the use of dairyproducts and eggs. A vegetarian does not eat any meat, poultry, game, fish, shellfish orby-products of slaughter.” (The Vegetarian Society of United Kingdom, retrieved onSeptember 16, 2015). Thus the most common type of vegetarians--lacto-ovovegetarians-- avoid eating any meat, while still indulging in eggs and dairy products.There have been many definitions of veganism over time. An early definition isas follows: “Veganism is the practice of living on the products of the plant kingdom tothe exclusion of flesh, fish, fowl, eggs, honey, animal milk and its derivatives, andencourages the use of alternatives for all commodities derived wholly or in part fromanimals” (1944 definition from The Vegan Society).Although complete, this definition does not account for the numerous differencesamong vegans. Some vegans scrupulously respect the above definition and avoid eatingor using any animal products. Other vegans are less strict both in their diet and in theproducts that they use. For example, some vegans include honey, an animal product, intheir diet, and others wear wool, also an animal product, because sheep are not killedwhen wool is harvested. Cherry (2006) indeed found that half of all self-defined vegansthat she interviewed did not adhere strictly to the vegan society definition of veganism.1pulses are grain legumes3

Let us, then, examine the different forms of vegetarianism/veganism. Asmentioned, strict vegans refuse to eat animal flesh and refuse to use any products derivedfrom animals. Raw vegans avoid consuming either the flesh of animals or any foodproducts of animal origin. Additionally, raw vegans only eat either uncooked food orfood cooked at a low temperature so as to avoid the destruction of micronutrients and theproduction of harmful chemicals which may occur during cooking. Fruitarianism,juicearianism and sproutarianism are subcategories of raw veganism. Fruitarianismconsists of a diet of at least 75% fruit. Juicearianism is a diet consisting mainly ofdrinking fruit and/or vegetable juice. Sproutarianism is a diet consisting predominantlyof eating sprouts.Continuing with our examination of the different forms ofvegetarianism/veganism, lacto-ovo vegetarians avoid eating meat but do consume eggsand dairy products. Finally, pescetarians, while avoiding meat, do eat fish.We can see from the above variation from the strict definition of veganism thatthe consumption of an “animal” depends on its definition. If it is considered as a “real”animal, that is, an animal capable of feeling, vegans will not consume it. For the purposeof this study, we will assume that vegans and vegetarians exclude the consumption ofanimals belonging to any of the following four categories: amphibians, birds, mammals,and reptiles.4

A BRIEF HISTORY OF VEGETARIANISM/VEGANISMIt is difficult to trace the historical foundations of vegetarianism, since theconcept that eating animals is wrong has existed in many cultures for many thousands ofyears.As far back as the 6th Century BC, Pythagoras was vegetarian and madevegetarianism mandatory for his disciples (Iacobbo & Iacobbo 2004). However, prior tothe nineteenth century, most people were restricted to a local food diet. Only after theIndustrial Revolution did middle-class individuals have a wider choice of dietary intake,as well as the income to purchase a wider variety of foods. (Leneman 1999:219-20).The History of Vegetarianism in EuropeWith this wider choice of food, considerations about proper nutrition becameimportant at the end of the nineteenth century, and debates about eating meat becamemore common. The first vegetarian society, The Vegetarian Society located inManchester, Great Britain, was founded in 1847 (Leneman 1999:219). At that time, avegetarian diet was considered extreme by non-followers. This was true even thoughvegetarian restrictions concerned only the eating of meat, while the consumption of eggsand dairy products were not questioned. Nevertheless, once ethical reasons for not eatingmeat were raised, it became difficult not to extend ethical questions about theconsumption of other sources of animal products, such as the consumption of eggs anddairy products. Indeed, as early as 1909, debates occurred within the vegetarianmovement concerning eggs and dairy products. Debates arose rapidly about the abusecommitted against animals when consuming these products. The exploitation of cows for5

their milk and their being slaughtered when they no longer could produce milk, as wellas the killing of many bull calves, were questioned in particular. One bull can inseminatemultiple cows and also bulls do not produce milk. Additionally, some debates occurredabout the healthfulness of dairy products, with some people arguing that diseases weretransmitted from animals to humans through the consumption of milk (Leneman1999:223-4). Realizing the sanitary risks as well as abuse perpetrated to animals whileconsuming eggs and dairy products, an increasing number of vegetarians were slowlymoving towards a more vegan diet.In 1910, Rupert H. Wheldon wrote what could be considered the first vegancookbook (even though the term, “vegan,” had not yet been coined) entitled, No AnimalFood. In 1934, the editors of the Vegetarian Society of Manchester’s monthly journalremarked that "the question as to whether dairy products should be used by vegetariansbecomes more pressing year by year," (from the Vegetarian Society of Manchester’smonthly journal, in Leneman 1999:221). Members of the Vegetarian Society requestedthat a section of the journal be dedicated to the controversy over the consumption ofeggs and dairy products, but the request was denied. Consequently, Donald Watson,Secretary of the Leicester Vegetarian Society, began a newsletter in 1944 on the nonconsumption of eggs and dairy products. Following the publication of this newsletter,Watson decided to break from the Leicester Vegetarian Society and to found a societythat would be in accordance with the concept of neither eating eggs nor dairy products.He called the new association The Vegan Society, coining the word, “Vegan”, from theword VEGetariAN (Leneman 1999).6

The History of Vegetarianism in AmericaThe vegetarian movement in the United States was greatly amplified by themigration of members of the Bible-Christian Church from England to the United Statesin 1817 (Shprintzen 2013). To be a member of this church, founded in 1809, individualshad to refrain from drinking alcohol and had to adopt a vegetarian diet. According toIacobbo & Iacobbo (2004), a particular verse in the Bible was responsible for theconversion to vegetarianism of this community, namely, Genesis 1:29-30, which statesthat humans should only consume plants and fruits.29 And God said, Behold, I have given you every herb bearing seed, which is upon theface of all the earth, and every tree, in the which is the fruit of a tree yielding seed; toyou it shall be for meat.30 And to every beast of the earth, and to every fowl of the air, and to every thing thatcreepeth upon the earth, wherein there is life, I have given every green herb for meat:and it was so.Genesis 1:29-30 King James VersionWhen two clerics of the Bible-Christian Church, along with 40 members, escapedthe persecution of the British and migrated to Philadelphia in 1817 to establish theirchurch in the United States, they helped to promote their principle of non-meat eating inthe United States, even though there were already small vegetarian communities existingin the US (Iacobbo & Iacobbo 2004).Sylvester Graham (1794–1851) greatly contributed to the diffusion ofvegetarianism in America. During the cholera epidemic of 1832, he had a dramaticallyopposite view on how to avoid contracting the disease than did most physicians of histime. While most doctors recommended the avoidance of fruits and vegetables as well as7

encouraging the heavy consumption of meat, Graham advocated the consumption ofwhole grain bread instead of white bread, as well as the total avoidance of meat, alcohol,and tobacco (Iacobbo & Iacobbo 2004). Graham, like the members of the BibleChristian Church, believed that the Bible was encouraging people to be vegetarian. Healso strongly believed that meat-eating was responsible for alcohol consumption and thatby stopping the consumption of meat, the craving for drinking alcohol would disappear.Since the term, vegetarian, was not widely used at the time, his movement was calledGrahamism and his followers, the Grahamites.William Alcott (1798-1859), although trained as a mainstream doctor, rather thanas a doctor using alternative medicine, strongly believed that a vegetarian diet was thekey to good health, rather than the use of medicines for this purpose. Alcott did notconsume any meat, nor any dairy products, and therefore his food consumption, mostlikely, would approximate what today we would call veganism. He promoted thevegetarian diet by means of publishing books and magazines (Iacobbo & Iacobbo 2004).Both Alcott and Graham became the most influential leaders of the vegetarianmovement in the United States at that time. Some Grahamites created organizationssuch as The American Physiological Society (APS), for which both Graham and Alcottlectured. Later on, some Grahamites detached themselves from the church anddisconnected the concept of vegetarianism from the religion. The APS became focusedon studying health and diet based on scientific facts rather than on religion and topromote the avoidance of meat based on medical science (Shprintzen 2013).8

In 1850, only a few years after the British Vegetarian Society was created, theAVS, the American Vegetarian Society, was created with the aim of reuniting thedifferent movements promoting a meatless diet (Shprintzen 2013). A year later, in 1851,the death of Sylvester Graham shook the vegetarian movement. Graham’s feeble health,and subsequently his early death, made some individuals question the healthiness of thevegetarian diet (Iacobbo & Iacobbo 2014). The Vegetarian Movement continued tospread nonetheless after Graham’s death, because numerous partisans, as did Grahamand Alcott previously, advocated for the vegetarian cause.Iacobbo and Iacobbo (2004:126) explained how innovations helped spreadvegetarianism at the beginning of the twentieth century. The discovery of vitaminsallowed nutritionists to see the benefits of a diet consisting of an abundance of fruits andvegetables. New studies about not needing as much protein as previously thought in adiet arose and contributed to opening individuals’ minds about the danger of eating toomuch meat. Technical innovations, such as refrigerated trucks, also helped the transportof non-local fruits and vegetables. Both scientists and doctors began to search for othersources of protein than meat. Dr. John Harvey Kellogg (1852-1943) in particular,revolutionized the American breakfast with his ready-to-eat cereals, causing many togive up their traditional breakfast which included sausage.Yet, the Great Depression and the Dust Bowl of the 1930s seriously impeded thegrowth of the Vegetarian Movement. Not only were people impoverished and willing toeat whatever they could afford, whether vegetable or meat, but also the meat industrybegan to massively advertise about the necessity of eating more meat (Iacobbo &9

Iacobbo 2004). Following the Dust Bowl, State and Federal governments started tosubsidize farmers to make meat affordable even to the poorest. The drop in the price ofmeat together with the convincing and powerful message from the Meat Industry, keptvegetarianism in America a dietary practice exercised by a minority even to this day.There has been, however, a resurgence in interest in the vegetarian movement during the1960s-1970s with the countercultural movement. Numerous “hippies”, who envisioned acruelty free world as well as a concern for the environment, became vegetarians.(Iacobbo & Iacobbo 2004). The book by Iacobbo & Iacobbo (2004) was heavily reliedupon in this section because it was the first complete history of vegetarianism in theUnited States and because it is fairly recent.Vegetarianism/Veganism TodayToday, approximately five percent of the American population considerthemselves as vegetarian (Gallup 2012), and two percent of Americans considerthemselves as vegan. As stated before, vegetarians and vegans in the US still remain aminority and suffer from stereotyping. Nonetheless, few people in America do not knowabout vegetarianism today, and even veganism is slowly becoming more popular. Wehave seen through the history of the vegetarian/vegan movement that the social andpolitical context of a given time influences the propagation or the limitation of amovement. Vegetarianism/veganism is part of a large and complex social system, and itsdiffusion or restriction not only depends on individual choice, but is greatly impacted bylarger social forces. For example, state and federal governments, by subsidizing the meatand dairy industry, allow meat and dairy products to be more affordable than vegetarian10

and vegan food, thus discouraging many people from even considering beingvegetarian/vegan. This support from the government to the meat and dairy industrythrough the subsidization of their food products is a reciprocal process (Simon 2013).Indeed, in return, the meat and dairy industry, through the help of their lobbies, play animportant role both in electing and re-electing members to government who advocate fortheir cause.The possibility that the U.S. government can create an unequal access to certainfood can be explained by the fact that the government, as a social and politicalinstitution, is itself embedded in a racist, sexist, and classist system. This system ensuresthat the vast majority of Congress members are elite white men whose interests are notprimarily directed toward the betterment of the poor. What started as governmental helpprograms to farmers to reduce the severe consequences of the Dust Bowl for Americanagriculture during the 1930s, today almost exclusively benefit the big factory farms, andnot small farmers. These factory farms are problematic for several reasons. First, theirextensive size requires the use of heavy fertilizers and pesticides for the production ofcrops, as well as the confinement of animals in small spaces, which sometimes requiresthe mutilation of some animal parts, such as the cutting off the beaks of chickens andturkeys as well as the cutting of the cows’ and pigs’ tails. Because of their confinement,animals are injected with antibiotics to prevent illnesses. They are also provided withhormones to grow more quickly. The excessive amount of waste produced by thenumerous confined animals is also a source of air and water pollution. As we can see, thedevelopment of large factory farms has severe consequences for the treatment of11

animals, for the health both of animals and humans, as well as for the environment. Eventhough vegetarianism and veganism have always existed, the recent spike of interest forthese diets can be explained at least partially, as a reaction to the environmental, health,and animal right issues that the creation of factory farms has demanded.12

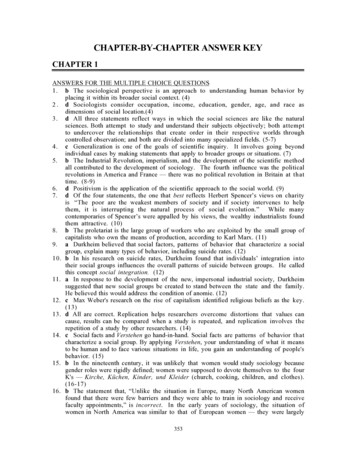

METHODSFor this research, I analyze the literature concerning vegetarianism/veganism interms of the important demographic factors of race, class, and gender. Little research hasbeen done about the movement and in particular about how and why people areconverted to vegetarianism/veganism. The literature collected on the subject is thencompared with accounts by twenty well-known vegetarians/vegans selected better tounderstand the vegetarian/vegan movement. Finally, I select five of the twentyvegetarians/vegans who have provided longer biographies, to obtain even more detailedinformation about their conversion to vegetarianism/veganism, as well as the variousfactors that either facilitated or obstructed their conversions.Below is a table of twenty contemporary well-known vegetarians/vegans selectedfor this study. The table provides the name, the profession, the race, the social class andthe gender of the vegetarians/vegans studied.13

Table 1. Twenty Contemporary Well-Known Vegetarians/VegansNamePaul McCartneyProfessionRaceContemporarySocial ClassLower upperclassLower upperclassGenderMusician, songwriter,singerMusician,photographer, animalrights activistSinger, songwriter, andmusicianWhiteWhiteLower upperclassMaleFounder of the largestraw, organic produceco-operative in the USLatinoUpper middleclassFemaleAmerican politician,environmentalistTalk show host,comedianActress, singer, fashionmodelFounder of theassociation“Régénère”, speakerAuthor of many bookson health and raw foodBiochemistWhiteLower upperclassLower upperclassLower upperclassUpper middleclassMaleMaleDistinguishedProfessor of Law,Animal rights advocateAmerican politician,President of the U.S.A.from1993 to 2001Buddhist teacher,authorWhiteUpper middleclassUpper middleclassUpper middleclassWhiteLower upperclassMaleAsianMaleWhitePamela AndersonPresident of People forthe Ethical Treatmentof Animals (PETA)Model, actressN/A. Belongs toa religiouscommunityUpper middleclassFemaleCarl LewisAthleteBlackKaryn CalabreseRaw foodistrestaurateur, holistichealth teacherBlackLower upperclassLower upperclassUpper middleclassLinda McCartneyRichard MelvilleHall, better known as“Moby”Kristina CarrilloBucaramAlbert Arnold Gore,Jr. (Al Gore)Ellen DeGeneresBrigitte BardotThierry CasasnovasDouglas GrahamT. Colin CampbellGary L. FrancioneBill ClintonThich Nhat HanhIngrid maleFemaleFemaleMaleMaleMaleFemaleMaleFemale

Table 1. ContinuedNameProfessionRaceRussell SimmonsBusinessman, authorBlackJared LetoActorWhiteRussell BrandComedianWhiteContemporarySocial ClassLower upperclassLower upperclassLower upperclassGenderMaleMaleMaleAmong these well-known vegetarians/vegans, the accounts of five of them will bestudied in more detail on selected topics about vegetarianism/veganism. These fiveindividuals are:1.2.3.4.5.Paul McCartneyKristina Carrillo-BucaramEllen DeGeneresThierry CasasnovasDr. T. Colin Campbell15

DEMOGRAPHIC FACTORS INFLUENCING THE CONVERSION TOVEGETARIANISM/VEGANISMIn the following sections, I identify patterns among vegetarians/vegans moregenerally, relative to their demographic characteristics. My intent is to show that thesystemic forces of race, class, and gender impact the vegetarian/vegan movement. Otherdemographic factors such as age and marital status will also be discussed in regards tovegetarianism/veganism. First, I look at the literature on race, class, gender as well as onage and marital status as related to vegetarianism/veganism. Next, I compare thisliterature with the demographic profiles of the twenty contemporary vegetarians/veganspreviously selected.Gender Differences Among Vegetarians/VegansMany studies have been done on the differences of consumption of meat bygender. The majority of these studies show a greater proportion of women beingvegetarian/vegan than men (Vinnari et al. 2009). Phillips et al. (2011) in particular,demonstrate the differences by gender in the attitude and consumption of meat in elevenEurasian countries. The authors noticed that women avoid eating meat more than men,and that there were three times as many female vegetarians as male vegetarians in theirstudy. The Economic Research Service of the US Department of Agriculture (USDA)has combin

vegetarianism/veganism included the importance of having a strong vegetarian/vegan social network, of having the support of close friends and family, and the important role that media plays in the diffusion of the movement. On the other hand, factors keeping people from becoming or from staying vegetari