Transcription

Modern art in your lifeBy Robert Goldwater, in collaboration with Renéd'HarnoncourtAuthorGoldwater, Robert, 1907-1973Date1949PublisherThe Museum of Modern ArtExhibition URLwww.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/2744The Museum of Modern Art's exhibition history—from our founding in 1929 to the present—isavailable online. It includes exhibition catalogues,primary documents, installation views, and anindex of participating artists.MoMA 2017 The Museum of Modern Art

The Museum of Modern ArtModern Art in Your Life

TK Museum of Modern Art

In celebration of its 20th anniversary in 1949, the Museum of Modern Art presented two exhibitions, one called Timeless Aspects ofModern Art, the other Modern Art in Your Life. The first of thesedealt with the relationship between modern art and the art of pastperiods, and was designed to show that modern art is not an isolated phenomenon in history, but an integral part of the art of allages. The ideas developed in this exhibition were incorporated in theportfolio Modern Art Old and New, published by the Museum in1950.The second exhibition, Modern Art in Your Life, on which thispublication is based, was designed to show that the appearance andshape of countless objects of our everyday environment are relatedto, or derived from, modern painting and sculpture, and that modern art is an intrinsic part of modern living.These exhibitions and publications were not prepared as justifications of the artistic merit of modern art. Works of art need nojustification beyond their own appeal. The aim of this special seriesis to demonstrate, persistent doubters to the contrary, that modernart, like the art of any period, is both rooted in tradition and trulypertinent to its own time.

AffcrtAHort*.11 -TRUSTEESOF THE MUSEUMOF MODERNARTDAVID ROCKEFELLER,WILLIAM S. PALEY,CHAIRMAN OF THEMRS.BLISSA. M. BURDEN, PRESIDENT;NER COWLES,BOARD;PARKINSON,HENRY ALLEN MOE,VICE-CHAIRMEN;VICE-PRESIDENTS;ALFREDH. BARR, JR.,*MRS.WOODS BLISS, *MRS. W. MURRAY CRANE, JOHN DE MENIL,NONCOURT, MRS. C. DOUGLAS DILLON, MRS. EDSEL B. FORD,GOODYEAR,*MRS.SIMON GUGGENHEIM,WALTER HOCHSCHILD,ALBERTD. LASKER,WILLIAMJAMES THRALL SOBY, RALPH F. COLIN, GARD*JAMESWALLACEW. HUSTED,JOHN L. LOEB,K.PHILIPC.ROBERTRENE d'hAR*A. CONGERHARRISON,MRS.JOHNSON,MRS.MRS. HENRY R. LUCE,PORTERA.MCCRAY, RANALD H. MACDONALD, MRS. SAMUEL A. MARX, MRS. G. MACCULLOCH MILLER,MRS.JOHN D. ROCKEFELLERCHARLES3RD,S. PAYSON,* DUNCAN PHILLIPS,NELSON A. ROCKEFELLER,MRS.*PAUL J. SACHS,MRS. DONALD B. STRAUS, G. DAVID THOMPSON, *EDWARD M. M. WARBURG,MONROE WHEELER, JOHN HAY WHITNEY.* Honorary Trustees for Life

Modern Art in Your LifeBy Robert Goldwater In Collaboration with Rene d HarnoncourtThe Museum of Modern Art, New YorkDistributed by Doubleday & Company, Inc., Garden City, New York

AcknowledgmentsWe are greatly indebted to the following institutions and firms fortheir help in making possible this publication and the exhibition onwhich it is based: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York;The Cloisters, New York; Bonwit Teller, Inc., New York; DelmanShoes, New York; The Herman Miller Furniture Company, Zeeland,Michigan; Knoll Associates, New York; Laverne Originals, NewYork; Lord & Taylor, New York; The Miller Company, Meriden,Connecticut; Saks Fifth Avenue, New York.We further want to thank the following persons for their valuableassistance and generous loans: Mr. Andre de Vilmorin, Paris; MmeLilly Dache, New York; Mr. and Mrs. Lyonel Feininger, New York;Mr. Leland Hayward, New York; Mr. Leo Manso, New York; Mr.Herbert Matter, New York; Mr. George Nelson, New York; Mr.Harry F. O'Brien, New York; Mr. Paul Rand, New York; Mr. CharlesRatton, Paris; Mr. Nelson A. Rockefeller, New York; and Mrs. Burton Tremaine, Meriden, Connecticut.R. d'H. and R. G.Cover design by Paul RandThird edition, revisedCopyright 1953. The Museum of Modern Art, 11 West 53 Street, New York19, N. Y.Printed in the United States of America

IntroductionModern art plays an important part in shapingthe world we live in. Sensitive to the conditionsof the modern world, it has transformed and remade much of the outward appearance of familiar scenes. Whether we are aware of it ornot (and whether we like it or not), it helps toproduce the environment of our daily lives.As the artist's concepts are molded by thetrends and aspirations of his age, so in turn hemolds the appearance of objects around him.The role of a machine civilization in fatheringMondrian's love of the right angle and the clean,flat surface may be argued, but there is no doubtthat his work gives form to the passionate concernwith mathematical order that made mechanizationpossible and that the esthetic of his pictures hasentered into our way of seeing the world. Whenthe architect strips his walls of ornament, whenthe jacket designer makes up his page with a fewrigorous lines against large immaculate areas,when the package designer limits his appeal tosquare-cut letters and a minimum of balanced rectangles, they all share Mondrian's delight in abold and subtle simplicity. In like fashion, the advertising artist, silhouetting his product against adramatic deep and empty space, accepts the surrealist vision, while the furniture designer bendshis plywood into freely molded shapes that havetheir counterpart in the works of Arp and Miro.These similarities suggest that the artist hasgiven form to a vision which the designer thenmakes his own; and indeed the designer oftenfrankly follows after the artist, adapting to hisown uses the latter's invention and discovery.(This is especially true when the artist is on occasion also a designer.) But as often these resemblances connote a common point of view5Introductionadopted independently by artist, architect anddesigner alike — similar needs provoking similaresthetic discoveries —and it is incorrect to speakof source and derivation. But however they mayarise, the forms of modern art are part ofmodern living.This directly contradicts the point of viewthat the modern artist is isolated from the restof the world, and his work therefore withoutmeaning for his fellow men. Many people whoare critical of modern art accept its parallelsand offshoots in the field of design with familiar,even friendly, unconcern. They readily admirethe sensitive balance in a fine example of contemporary typography, or the magic mood of adisplay window, without realizing that in themthey pay tribute to the vision and achievementof the artist. They are still self-conscious whenthey approach modern art even though they areon easy terms with everyday modern designsand readily accept them as reflections of thetwentieth century.For the older periods of the world's art wetake this pervasive unity for granted. We assume a natural relation between the Greek vaseand the Greek temple. We enjoy the similaritiesamong the Gothic cathedral, sculpture, tapestryand chest. We admire the unity in the architecture, pewter ware and portraits of a New England house. Belonging to the same world, we expect them to have certain essential likenesses; thesame spirit infuses them all, creations of the artist, artisan, or designer, and as we recognizeit we call it the "style" of the time.Such similarities are aids to insight. By comparison and contrast we see with greater precision and enjoy with deeper understanding. But

no one would for an instant suppose that the pottery is needed to justify the picture, the furniture to excuse the architecture, nor that the inspiration of the artist exists merely to jog theinventive powers of the designer.Now, as in the past, the work of art is its ownreason for being. In the common phrase, it is agood in itself. As a distillation of vision andimagination, as a summation of experience, iteffectively changes our way of seeing things.And since the designer, being similarly concerned with the organization of visual forms andsymbols, is sensitive to this power within thework, it is only natural that he should be the firstto come under its influence and share in its inspiration.But, paradoxically, were the painter or sculptor to think beyond his art to this practical effecthe would forfeit the image-making power thatgives him his hold upon the minds of others.Only by striving for the greatest consistency andexpressiveness on his own terms as an artist canhe achieve the highly charged concentrate of thework of art. If he relaxes his vigilance, the intensity is gone; and if he considers application,use and fitness beyond his immediate estheticconcern he defeats his own purpose.Nor are these instances of parallels, influencesor affinities with the various useful arts intended as an apology — for modern art needs no utilitarian justification. They are simply a selecteddemonstration that, in fact, modern art has beena source and a catalyst for much of our everydayenvironment.One of the characteristics of modern art is itsdiversity. Not all styles of art, much less all individual artists, have directly affected the practice of the designer. Whole schools and manyimportant and representative masters have beenwithout such stylistic connections. Their work,nevertheless, has its effect on our view of theworld, as when a Picasso or a Beckmann createssymbols of content and meaning that compresswide sums of significant experience hut haveA Saint Writing. French. Late XIV or early XV century. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New Yorklittle bearing on the designer's purpose. In othercases the effect of an artist's works may permeateour world in ways too gradual and subtle forspecific illustration: a Matisse, successfully employing new hues and harmonies, has increasedour sensitivity to the range and nuance of color;a Chagall has made us willing to accept a newtype of fantasy; a de Chirico has given us anew sense of the mysterious beneath the commonplace. In the long run such changes, althoughthey are difficult to pin down, affect the designerjust as they enlarge the esthetic experience of usall.The styles of modern art are not reflectedequally in all kinds of applied design. There arenatural affinities of technique and mood thatmake a particular style more adaptable to onefield than another. The sudden shock of surrealism's dream world is wonderfully suited to theshow window, the stage set, and the more ephemeral sort of advertisement. The clear-cut, clearlyIntroduction6

left: Alexander the Great. Detail from one of the nine Heroes Tapestries. French,about 1385. The Cloisters, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, center:Oak chair. French, late XV or early XVI century. The Metropolitan Museum ofArt, New York, right: Detail, carved oak woodwork from Abbeville. French, earlyXVI century. The Cloisters, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New Yorkbounded, carefully balanced areas of geometricabstract art seem naturally related to architectureand furniture, book design and packaging. Wesee at once how Leger's bold simplifications andbright colors, LeCorbusier's smooth volumes, canbe extended to the large surfaces of the poster.But we should not assume that each field ofdesign closely parallels a specific school ofpainting. Technique and function are not thesole determinants of even the most directly useful objects. Their style is also subject to taste.Thus some kinds of furniture reflect a love of theright angle similar to Mondrian's, while othersemploy shapes closer to the free forms of Miroand Arp or a combination of both styles. Weshould also beware of looking for derivations ofa specific applied design from specific works ofart.7IntroductionThe relation between styles of art and typesof design is general rather than particular. Evenwhere direct influence exists — for instance, whena designer works at will in a variety of mannersso that we know he has studied them all —it stemsfrom a whole tendency and style rather than fromindividual works. In fact, very often the stylehas reached the designer only through a seriesof intermediaries and he is unacquainted withthe works of art which also embody the principles of form upon which he is organizing hismaterial. This is the more widespread and themore significant influence: the attraction exertedby whole schools and styles upon the appearanceof familiar, everyday things.This attraction does not guarantee quality.The designer working in the modern vein doesnot for that reason alone produce a result worthy

WRENCHESANDACCESSOA!BreastDrillie' -« V . A"*», HST! "sst '**& ,i\:J 1 l! -

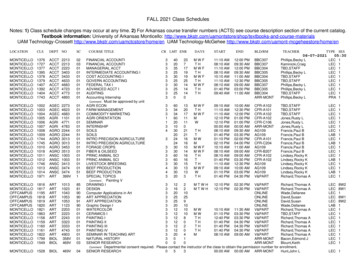

1920 vs. 1944:upper left: Linoleums. Page 601, Montgomery Ward Catalogue, 1920upper right:Armstronglinoleums.Page 545, Montgomery Ward catalogue, 1944lower left: Miscellaneous tools, Page735, MontgomeryWard Catalogue,1920lower right: Miscellaneous tools. Page699D. Montgomery Ward Catalogue,1944of his source. But the pervasive power of modern art is nowhere shown so well as in the way itsforms turn up in designs that are mediocre, ifnot worse.Nevertheless, we may believe that the moderndesigner stands a greater chance of success thanhis more conventional colleague because he ismore vital and contemporary. Even his failureis more interesting than a copy of the past, andhis best works are creative contributions to modern life.This survey does not attempt to be exhaustive;it must permit typical works to stand for all therelevant aspects of modern painting and sculpture. It can do no more than include characteristic examples of the countless objects of utilitariandesign conceived in a contemporary spirit, arranging them not by the time and place of theirmaking but according to their esthetic kinship.Through thus consciously associatingthe"pure" art and the "applied" without minimizing the independent existence of either, some ofthe strangeness of the former may wear off. Wemay more readily take for granted that the visionof the modern artist, wherever and in whateverform it is found, is an integral and consistentforce of our time.Tubes of Colgate's DentalCream, left: 1925; right:1949ISf-Lv i%ATtklRHMl, aK'sJ9Introduction

AbstractGeometricFormiPmondrian:Composition. 1925. Oil on canvas, 15J4 x12*34". Museum of Modern Art, gift of Philip C. Johnsonmondrian: Composition in White, Black and Red. 1936.Oil on canvas, 4034 x 41". Museum of Modern Art, giftof the Advisory CommitteeThe following pages illustrate a wide variety ofdesigns alike in their use of strict geometricform and asymmetrical balance. They are aliketoo in their severe limitation of elements usedto create a design.lurcat: House of Mme. Froriep de Salis. Boulogne-surSeine, France. 1927The objects shown together on pages 10 to 13impose the severest restraint. They take pleasurein the straight line and the right angle, and avoidthe curve. They all employ large smooth rectangles, each of which is of a uniform intensitywithout shading or modeling. These rectangularareas are at once divided and united by narrowerbands. At one extreme (the house by Lurgat andthe storage wall by Nelson), these bands approach simple contour lines; at the other (thefacade by Doering, cover for Technique Graphique ), the bands widen to become indistinguishable from the areas they divide. But theline is never merely a boundary, for it alwaysnelson: Storage wall unit for The HermanFurniture Company, Zeeland, Michigan. 1949BMW"AbstractGeometricFormMiller10

Cover design for La TechniqueGraphique. Paris. 1934olson: Cleansing tissue package for ring: House in Greenburgh, New York. 1938fixes a plane in depth and is located at a precisedistance in space from the other rectangles ofthe composition. The similarity with one or theother of Mondrian's two paintings at the top ofthe opposite page is apparent.Throughout these designs there is an even,over-all distribution of emphasis. As in the paintings, outlying edges count as much as the center.In the architecture centralized doorways givenimportance by increased richness of surface orornament are avoided, but doors, windows andopen entrances become integral parts of a composition of smooth, rectangularsurfaces. Incovers and packages, lettering, rather than beingAdvertisements for John Wanamaker, New York, andScott Radio Laboratories, Inc., Chicago. 194511AbstractGeometricFormbreuer:Desk. Bauhaus, Dessau. 1924prominently centered against a subdued background design, as it might have been formerly,is employed simply as one of the elements of thedesign, and its shape, coloring and position awayfrom the center change with the requirements ofcomposition. As the architect makes ornamentof his surface divisions, rather than applying ornament to them, so the designer uses block lettering in character with his ideal of severity.Technical considerations undoubtedly play animportant part in producing these results. Steeland glass and concrete impose certain requirements of handling; the technical possibilities ofmetal tubing, or the mechanical letter press, giverise to new shapes and arrangements. But these

breuer:Chair for Thonet Brothers, Inc. 1928breuer: Exhibition house. The Museum of Modern Art,New York. 1949results are not invariable: metal tubing need notbe bent in right angles; plots of land on a cityblock need not be assembled in narrow slabs,and zoning laws can be met in many ways;presses print dull colors as easily as bright, andvaried letters as well as uniform. One has only tocompare the banded divisions of the lobby designed by Haesler and the side of the IllinoisInstitute of Technology building; the diagonalbalance of the top of the Philadelphia SavingsFund Society skyscraper and the Kleenex container; the stripes of the end of the house byBreuer and the Nelson storage wall; the progressively recessed slabs of the Muschenheim interiorhaesler:1928Lobby of private residence.saarinenCelle, Germany.and eames: Desk. 1941AbstractGeometricForm12

yweese and Baldwin: Tea wagon. Lloyd1Manufacturing company. 1941irietveld:House. Skeleton construction.land. 1928Utrecht, Holand those of the Daily News and RCA buildings,and all of them with Mondrian's two canvases, torealize that here is the expression of a commonesthetic.As these examples show, its distribution iswide, in both time and place. Clearly the Dutcharchitect, Rietveld, was aware of specific detailsof paintings by artists with whom he was associated. But the same ideal is equally, if more generally, expressed in examples like the Saarinenand Eames desk, that have no such direct connection; while the detailed parallels reappearstrikingly (and perhaps consciously) in the recent storage wall.BauhausbocherWALTERQROPIU8L. nheim:1934ImmoGuldenapartment,New York.left: moholy-nagy: Title page. Neue Arbeiten der Banhaus JVerkstatten. Dessau. 1925. Museum of ModernArt, Graphic Design Collection13AbstractGeometricForm

howe and lescazes: Philadelphia Savings Fund SocietyBuilding. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. 1932left: papadaki: Coverdesign for ProgressiveArchitecture, July 1949,New Yorkhood and howells:1930Daily News Building, New York.chiitcfpr*imuscenter: cover design forDomus, May 1947. Milanright: Cover designfor Life, March 17, 1941.New YorkAbstractGeometricForm14

Like the Boogie Woogie, the related fagadeand textile are composed from the straight lineand right angle alone, as in the previous examples. But now the rectangular units they makeup are smaller and more numerous, and theirposition given by a more varied, though no lessprecise, sequence and system of coordinates. Theresult is a pulsating design, apparent freedomreally rigidly determined.aJJialingeri, delfino and terzaghi:house. Milan. 1944Detail from apartmentThe simplicity and clarity of this style, itsclear outlines and smooth surfaces, the self-contained repose of its balanced asymmetry, aboveall its conscious restraint and self-imposed severity, can earn for it the name of a modern classicism.The architectureof skyscrapers is generallythought of as determined entirely by use and construction. But both the examples opposite makeprominent use of asymmetrically arranged rectangles in receding planes.Three magazine covers show variations of thesame basic principles of severe angular andasymmetrical design.anni alrers:15AbstractSilk tapestry. Bauhaus, Dessau. 1927GeometricFormaaaaaaaaaaaalaaaa aft.0aa aa aaya amondrian: Broadway Boogie Woogie. 1942-43. Oil oncanvas, 50 x 50". Museum of Modern Art

breuer:1922Chair.Bauhaus,Dessau.Although these instances of the geometricalideal are still built of only the same few elements,the structural framework is relaxed, and morepresent by suggestion than actual statement. Verticals and horizontals are now limited to separated narrow rectangles and set with precisiongauged intervals and sizes against space. Thisspace is now free, not confined in discrete units,and its over-all unity is heightened rather thandiminished by the colored bands which punctuate but only momentarily interrupt its free flow.;gng JMfvan doesburg: Rhythm of a Russian Dance. 1918. Oilon canvas, 53} x 24 }/ ". Museum of Modern Art, acquired through the Lillie P. Bliss Bequestright: lissitzky: Title page. Erste Kestnermapp e, Prounseries. Hanover. 1923. Museum of Modern Art, GraphicDesign CollectionAbstractGeometricForm16

1TTTTTMIESvan der rohe : Floor plan of house. Berlin. 1931The result is a design less stern and forceful thanthe early Mondrian, but of an extreme eleganceand refinement. This sense of continuous spaceflowing around partitions which measure ratherthan enclose it, is one of the fundamental ideasto which the modern architect holds in designing his interiors. Note how this love of openspace is shown in Mies van der Rohe's floor plan,which also, simply in the arrangement of itsslender divisions, resembles Doesburg's Rhythmof a Russian Dance.l*OI.OI 14 V"***;"m V:' '''» ' ' ' marchi: Rug for G. Bronzini. Mestre, Italyleft: del renzio: Cover design for Polemic, May 1946.Rodney Phillips & Green Co., Ltd. London17AbstractGeometricForm

Nicholson: Relief. 1939. Synthetic material painted,32 J s x 45". Museum of Modern Art, gift of H. S. Edeand the artistStraight line and right angle are still prominent in the designs on this page, but two newelements are introduced. One is the circle, purestof all curved forms, which though it is now employed in contrast to the rigid line and rectangle,is yet of the same geometrically determined character. It does not disturb the calm of orderlybalance, since its movement is in upon itself. Theother new element is actual space. Where Mondrian and Doesburg convey position in space byshape of area, width of line, and intensity ofcolor, Nicholson employs actual bas-relief inwhich planes are stepped back and overlap, andshadows are cast. This translation into physicalactuality results in a certain matter-of-factness.In fabrics this recession is interpreted by anoverlapping of lines which establishes a seriesof planes in the same almost tangible way. InLoewy's radio cabinet, knobs and dials projectat varying depths against the asymmetrical balance of the rectangles. Note how these same features occur in the table set for two persons, withleft: loewy: Model S 40, communications receiver. TheHallicrafters Company, New York. 1946. Museum ofModern Art, Industrial Design Collectionball:Geometric arrangementof tableware. 1947left: morton: Jacquard woven fabric. England. 1946.right: Raymond: Printed textile. Cyrus Clark, distributor. 1941. Museum of Modern Art, Industrial DesignCollectionAbstractGeometricForm18

mats and stoneware moved away from any central axis.With this last group of geometrically abstractworks we move into a realm of much greaterfreedom. In all the preceding works the use ofthe right angle applied not only to divisionswithin the planes of the pictures but to the relation of planes to the observer: these were always placed at 90 to his line of sight; his position was as determined as the rest. With Gabo'sColumn he is now free to move, and as he does,the dominant right angle and circle of the planform and reform into any number of angles andellipses. Thus an entirely new sense of directionalfreedom within a three-dimensionalspace iscreated, an interpenetrationof lines of force,and a dynamic balance. These elements, employed somewhat more statically, are given animmediate application in the stage set by a member of the same milieu.gabo: Column. 1923. Glass, plastic, metal, wood, 41" high.Collection The Phillips Academy, Andover, Massachusettsprampolini: Model for MagneticItaly. Prior to 192519AbstractGeometricFormTheatre.

\pereira: White Lines, 1942. Oil, with variousfillers, on vellum, 25% x 21%". Museum ofModern Art, gift of Edgar Kaufmann, Jr.malevich: Suprematist Composition. 1914. (After pencildrawing of 1913.) Oil on canvas, 22% x 19". Museum ofModern Art, Purchase FundIRADIOo'brien: Cover design for DoesRadio Sell Goods?, ColumbiaBroadcasting System, New York.1931jones: Album cover for Columbia Records. 1948.Museum of Modern Art, Graphic Design CollectionAbstractGeometricForm20

In the Malevich and the Lissitzky, this freedom now permits the use of the diagonal in composition, and the abandoning of the right anglein the forms composed. It also makes for a suggestion of vector movement with an all enveloping, endless space. Since position no longer existsby virtue of rigid balance, by implication thatposition can change, and the surrounding openness implies that it will. Thus we move closer tothe border line of free form freely situated indeep space.Poster, book cover, and record album all possess these qualities in varying proportions, Hieirelements are still the sparse few we have notedthroughout this whole abstract tendency, butthey are placed with such apparent spontaneitythat the whole effect is light and open.lissitzky: Construction. Proun, 1919-23. Lithograph andcollage, 23 M x 17%". Museum of Modern Art, PurchaseFunddiaries191043say itfastoften.in colorKAFKAsubwaypostersleft: games: Poster for The Royal Society for the Prevention of Accidents. London. 1948, right: Nitsche: Poster for New York subway. 1917.Both, Museum of Modern Art, Graphic Design Collection21AbstractGeometricFormschockenand oldenburg:Jacketdesign.SchockenBooks, Inc. 1948. Museum ofModern Art, Graphic DesignCollection

GeometricallyRepresentationStylizedozenfant: The Vases. 1925. Oil on canvas, 51% x 38%.Museum of Modern Art, acquired through the Lillie P.Bliss BequestBoth the works of art and the applied designshere brought together under one title have thisin common: that they combine satisfaction ingeometric order with representation.Like geometrical abstraction they are attracted by theclean contour and the smooth surface. Stronghorizontals and verticals compose into over-allarrangements of a heavy, often massive stability.The desire for representation adds the new element of modeling; but the curved surfaces, likethe flat ones, remain smooth, and approximategeometric solids. Geometric order has its clearestphysical embodiment in machinery, and in thesedesigns even living things tend to be stylizedinto regular mechanical shapes.Thus representation takes on a symbolic quality. Elimination of individual accident and detail,emphasis on basic structure, make one objectstand for a whole class of objects: not "a" pitcherbut the essentials of "the" pitcher. Instead ofstraight line and plane surface, composition isbuilt of three-dimensionalundulating volumes,above all cylinder and sphere. Lighting is dramatic, with sharp contrast sometimes going asfar as silhouettes, sometimes producing exaggerated bulkiness; but like the objects it bringsinto sharp relief, it is a generalized lighting, inwhich specific source and naturalistic atmospheric effect are eliminated. There may be dramaticisolation of the object (Ozenfant painting) orthere may be an arbitrary grouping of detailsassembled according to the combined dictatesof composition and an idea spelled out (Legerpainting, Cassandre poster). Theoretically, anyrelative proportion of geometrical structure torealistic detail is possible, but the regular rhythmof geometric solid and measured interval isnever lost.Hindsight tells us that this is a style ideallysuited to the poster. Objects are recognizable,le corbusier: Still Life. 1920. Oil on canvas, 31% x39%". Museum of Modern Art, van Gogh Purchase FundGeometricallyStylizedRepresentation22

WAGON-BARcarlu: New York subway poster. 1947. MuseumModern Art, Graphic Design Collectionofbut elimination of detail makes them immediatelystriking. The parts suggest the whole and maybe brought together to tell a story since salientfeatures suggest much more than is shown. Thestructure of geometric stylization makes for aunified visual impression easily grasped, andstrong contrasts catch the attention. In posterssuch as those of Cassandre, Carlu, McKnightKauffer, these elements are employed in such aneconomical, meaningful way that they constitutea modern iconography built of visual symbolswhose full impact everyone can understand.vassos: Music room,World's Fair, 193923GeometricallyAmericaStylizedat Home.New YorkRepresentationcassandre: Poster for Compagnie Internationale des Wagons Fits. 1932. Museum ofModern Art, Graphic Design Collection

archipenko:WomanCombing Her Hair.1915. Bronze. 13%"high. Museum ofModern Art, acquiredthrough the Lillie P.Bliss Bequestmiwrru rRleger:Compass and Paint Tubes.10 4 x 14/4"- Museum of Modernward M. M. Warburgupper left: leger:The ThreeWomen(Le granddejeuner).1921. Oil on canvas, 72 % x 99".Museumof Modern Art, Mrs.Simon GuggenheimFundright:Mannequin.Paris.19291926. Gouache,Art, gift of EdAnderson:Poster for Shell OilCompany, England.1935. Museum of Modern Art, Graphic Design CollectionMOTC R!51GeometricallyREFER SHELL;StylizedRepresentation24

DUBONNETVIN TONIQUEAU QUINQUINAcassandre: Poster for Dubonnet SocieteAnonyme, Paris. 1932.

Modern Art, the other Modern Art in Your Life. The first of these dealt with the relationship between modern art and the art of past periods, and was designed to show that modern art is not an iso lated phenomenon in history, but