Transcription

T. LOBSANG RAMPATHE THIRD EYE(Edition: 22/04/2021)The Third Eye — (Originally published in 1956)This is where it all started; an autobiography about ayoung man's journey into becoming a medical Lamaand undergoing an operation to open the third eye. Weare shown a glimpse into the Tibetan way of Lamaserylife and the deep understanding of spiritual knowledge.Until this point in time lamasery life was unknown,even to those few who had actually visited Tibet.Lobsang enters the Chakpori Lamasery and learns themost secret of Tibetan esoteric sciences and muchmore.1/347

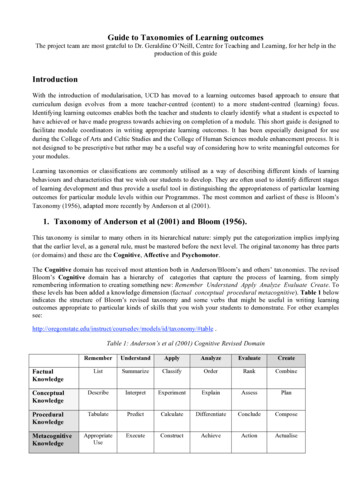

It is better to light a candle than to curse thedarkness.The Coat of Arms is surrounded by a Tibetan rosarymade up of one hundred and eight beads symbolisingthe one hundred and eight books of the Tibetan2/347

Kangyur. In personal blazon, we see two rampant sealpoint Siamese cats holding a lit candle. In the upperleft-hand of the shield we see the Potala; to the righthand of the shield, a Tibetan prayer wheel turning, asshown by the small weight which is over the object. Inthe bottom, left-hand of the shield are books tosymbolise the talents of writer and knowledge of theauthor, whereas to the right-hand side of the shield, acrystal ball to symbolise the esoteric sciences. Underthe shield, we can read the motto of T. Lobsang Rampa:‘I lit a candle’.3/347

Table of contentsTable of contents . 4Publishers' foreword . 5Author's preface . 7Chapter One Early days at home . 9Chapter Two End of my childhood . 44Chapter Three Last days at home . 64Chapter Four At the temple gates . 77Chapter Five Life as a chela . 99Chapter Six Life in the lamasery . 118Chapter Seven The opening of the Third Eye . 131Chapter Eight The Potala . 140Chapter Nine At the Wild Rose Fence . 163Chapter Ten Tibetan beliefs . 178Chapter Eleven Trappa . 207Chapter Twelve Herbs and kites . 219Chapter Thirteen First visit home. 255Chapter Fourteen Using the Third Eye . 269Chapter Fifteen The secret north—and yetis. 288Chapter Sixteen Lamahood . 305Chapter Seventeen Final initiation . 332Chapter Eighteen Tibet—Farewell! . 3424/347

Publishers' forewordThe autobiography of a Tibetan lama is a uniquerecord of experience and, as such, inevitably hard tocorroborate. In an attempt to obtain confirmation of theAuthor's statements the Publishers submitted the MS(i.e. manuscript) to nearly twenty readers, all persons ofintelligence and experience, some with special5/347

knowledge of the subject. Their opinions were socontradictory that no positive result emerged. Somequestioned the accuracy of one section, some ofanother; what was doubted by one expert was acceptedunquestioningly by another. Anyway, the Publishersasked themselves, was there any expert who hadundergone the training of a Tibetan lama in its mostdeveloped forms? Was there one who had been broughtup in a Tibetan family?Lobsang Rampa has provided documentary evidencethat he holds medical degrees of the University ofChungking and in those documents he is described as aLama of the Potala Monastery of Lhasa. The manypersonal conversations we have had with him haveproved him to be a man of unusual powers andattainments. Regarding many aspects of his personallife he has shown a reticence that was sometimesbaffling; but everyone has a right to privacy andLobsang Rampa maintains that some concealment isimposed on him for the safety of his family inCommunist occupied Tibet. Indeed, certain details,such as his father's real position in the Tibetanhierarchy, have been intentionally disguised for thispurpose.For these reasons the Author must bear and willinglybears a sole responsibility for the statements made inhis book. We may feel that here and there he exceeds6/347

the bounds of Western credulity, though Western viewson the subject here dealt with can hardly be decisive.None the less the Publishers believe that the Third Eyeis in its essence an authentic account of the upbringingand training of a Tibetan boy in his family and in alamasery. It is in this spirit that we are publishing thebook. Anyone who differs from us will, we believe, atleast agree that the author is endowed to an exceptionaldegree with narrative skill and the power to evokescenes and characters of absorbing and unique interest.Author's prefaceI am a Tibetan. One of the few who have reached thisstrange Western world. The construction and grammarof this book leave much to be desired, but I have neverhad a formal lesson in the English language. My‘School of English’ was a Japanese prison camp, whereI learned the language as best I could from English andAmerican women prisoner patients. Writing in Englishwas learned by ‘trial and error’. Now my belovedcountry is invaded—as predicted—by Communisthordes. For this reason only I have disguised my truename and that of my friends. Having done so muchagainst Communism, I know that my friends in7/347

Communist countries will suffer if my identity can betraced. As I have been in Communist, as well asJapanese hands, I know from personal experience whattorture can do, but it is not about torture that this bookis written, but about a peace-loving country which hasbeen so misunderstood and greatly misrepresented forso long.Some of my statements, so I am told, may not bebelieved. That is your privilege, but Tibet is a countryunknown to the rest of the world. The man who wrote,of another country, that ‘the people rode on turtles inthe sea’ was laughed to scorn. So were those who hadseen ‘living-fossil’ fish. Yet the latter have recentlybeen discovered and a specimen taken in a refrigeratedairplane to the U.S.A. for study. These men weredisbelieved. They were eventually proved to be truthfuland accurate. So will I be.T. LOBSANG RAMPAWritten in the Year of the Wood Sheep.8/347

Chapter OneEarly days at home“Oe. Oe. Four years old and can't stay on a horse!You'll never make a man! What will your noble fathersay?” With this, Old Tzu gave the pony—and lucklessrider—a hearty thwack across the hindquarters, andspat in the dust.The golden roofs and domes of the Potala gleamed inthe brilliant sunshine. Closer, the blue waters of theSerpent Temple lake rippled to mark the passing of thewater-fowl. From farther along the stony track came theshouts and cries of men urging on the slow-movingyaks just setting out from Lhasa. From near by came9/347

the chest-shaking ‘bmmn, bmmn, bmmn’ of the deepbass trumpets as monk musicians practiced in the fieldsaway from the crowds.But I had no time for such everyday, commonplacethings. Mine was the serious task of staying on my veryreluctant pony. Nakkim had other things in mind. Hewanted to be free of his rider, free to graze, and roll andkick his feet in the air.Old Tzu was a grim and forbidding taskmaster. Allhis life he had been stern and hard, and now as guardianand riding instructor to a small boy of four, his patienceoften gave way under the strain. One of the men ofKham, he, with others, had been picked for his size andstrength. Nearly seven feet tall he was, and broad withit. Heavily padded shoulders increased his apparentbreadth. In eastern Tibet there is a district where themen are unusually tall and strong. Many were overseven feet tall, and these men were picked to act aspolice monks in all the lamaseries. They padded theirshoulders to increase their apparent size, blackenedtheir faces to look more fierce, and carried long staveswhich they were prompt to use on any lucklessmalefactor.Tzu had been a police monk, but now he was drynurse to a princeling! He was too badly crippled to domuch walking, and so all his journeys were made onhorseback. In 1904 the British, under Colonel10/347

Younghusband, invaded Tibet and caused muchdamage. Apparently they thought the easiest method ofensuring our friendship was to shell our buildings andkill our people. Tzu had been one of the defenders, andin the action he had part of his left hip blown away.My father was one of the leading men in the TibetanGovernment. His family, and that of mother, camewithin the upper ten families, and so between them myparents had considerable influence in the affairs of thecountry. Later I will give more details of our form ofgovernment.Father was a large man, bulky, and nearly six feettall. His strength was something to boast about. In hisyouth he could lift a pony off the ground, and he wasone of the few who could wrestle with the men ofKham and come off best.Most Tibetans have black hair and dark brown eyes.Father was one of the exceptions, his hair was chestnutbrown, and his eyes were grey. Often he would giveway to sudden bursts of anger for no reason that wecould see.We did not see a great deal of father. Tibet had beenhaving troublesome times. The British had invaded usin 1904, and the Dalai Lama had fled to Mongolia,leaving my father and others of the Cabinet to rule inhis absence. In 1909 the Dalai Lama returned to Lhasaafter having been to Peking. In 1910 the Chinese,11/347

encouraged by the success of the British invasion,stormed Lhasa. The Dalai Lama again retreated, thistime to India. The Chinese were driven from Lhasa in1911 during the time of the Chinese Revolution, but notbefore they had committed fearful crimes against ourpeople.In 1912 the Dalai Lama again returned to Lhasa.During the whole time he was absent, in those mostdifficult days, father and the others of the Cabinet hadthe full responsibility of ruling Tibet. Mother used tosay that father's temper was never the same after.Certainly he had no time for us children, and we at notime had fatherly affection from him. I, in particular,seemed to arouse his ire, and I was left to the scantmercies of Tzu ‘to make or break’, as father said.My poor performance on a pony was taken as apersonal insult by Tzu. In Tibet small boys of the upperclass are taught to ride almost before they can walk.Skill on a horse is essential in a country where there isno wheeled traffic, where all journeys have to be doneon foot or on horseback. Tibetan nobles practicehorsemanship hour after hour, day after day. They canstand on the narrow wooden saddle of a gallopinghorse, and shoot first with a rifle at a moving target,then change to bow and arrow. Sometimes skilledriders will gallop across the plains in formation, andchange horses by jumping from saddle to saddle. I, at12/347

four years of age, found it difficult to stay in onesaddle!My pony, Nakkim, was shaggy, and had a long tail.His narrow head was intelligent. He knew anastonishing number of ways in which to unseat anunsure rider. A favourite trick of his was to have a shortrun forward, then stop dead and lower his head. As Islid helplessly forward over his neck and on to his headhe would raise it with a jerk so that I turned a completesomersault before hitting the ground. Then he wouldstand and look at me with smug complacency.Tibetans never ride at a trot; the ponies are small andriders look ridiculous on a trotting pony. Most times agentle amble is fast enough, with the gallop kept forexercise.Tibet was a theocratic country. We had no desire forthe ‘progress’ of the outside world. We wanted only tobe able to meditate and to overcome the limitations ofthe flesh. Our Wise Men had long realised that theWest had coveted the riches of Tibet, and knew thatwhen the foreigners came in, peace went out. Now thearrival of the Communists in Tibet has proved that to becorrect.My home was in Lhasa, in the fashionable district ofLingkhor, at the side of the ring road which goes allround Lhasa, and in the shadow of the Peak. There arethree circles of roads, and the outer road, Lingkhor, is13/347

much used by pilgrims. Like all houses in Lhasa, at thetime I was born ours was two stories high at the sidefacing the road. No one must look down on the DalaiLama, so the limit is two stories. As the height banreally applies only to one procession a year, manyhouses have an easily dismantled wooden structure ontheir flat roofs for eleven months or so.Our house was of stone and had been built for manyyears. It was in the form of a hollow square, with alarge internal courtyard. Our animals used to live on theground floor, and we lived upstairs. We were fortunatein having a flight of stone steps leading from theground; most Tibetan houses have a ladder or, in thepeasants' cottages, a notched pole which one uses atdire risk to one's shins. These notched poles becamevery slippery indeed with use, hands covered with yakbutter transferred it to the pole and the peasant whoforgot, made a rapid descent to the floor below.In 1910, during the Chinese invasion, our house hadbeen partly wrecked and the inner wall of the buildingwas demolished. Father had it rebuilt four stories high.It did not overlook the Ring, and we could not lookover the head of the Dalai Lama when in procession, sothere were no complaints.The gate which gave entrance to our centralcourtyard was heavy and black with age. The Chineseinvaders has not been able to force its solid wooden14/347

beams, so they had broken down a wall instead. Justabove this entrance was the office of the steward. Hecould see all who entered or left. He engaged—anddismissed—staff and saw that the household was runefficiently. Here, at his window, as the sunset trumpetsblared from the monasteries, came the beggars of Lhasato receive a meal to sustain them through the darknessof the night. All the leading nobles made provision forthe poor of their district. Often chained convicts wouldcome, for there are few prisons in Tibet, and theconvicted wandered the streets and begged for theirfood.In Tibet convicts are not scorned or looked upon aspariahs. We realised that most of us would beconvicts—if we were found out—so those who wereunfortunate were treated reasonably.Two monks lived in rooms to the right of thesteward; these were the household priests who prayeddaily for divine approval of our activities. The lessernobles had one priest, but our position demanded two.Before any event of note, these priests were consultedand asked to offer prayers for the favour of the gods.Every three years the priests returned to the lamaseriesand were replaced by others.In each wing of our house there was a chapel.Always the butter-lamps were kept burning before thecarved wooden altar. The seven bowls of holy water15/347

were cleaned and replenished several times a day. Theyhad to be clean, as the gods might want to come anddrink from them. The priests were well fed, eating thesame food as the family, so that they could pray betterand tell the gods that our food was good.To the left of the steward lived the legal expert,whose job it was to see that the household wasconducted in a proper and legal manner. Tibetans arevery law-abiding, and father had to be an outstandingexample in observing the law.We children, brother Paljör, sister Yasodhara, and I,lived in the new block, at the side of the square remotefrom the road. To our left we had a chapel, to the rightwas the schoolroom which the children of the servantsalso attended. Our lessons were long and varied. Paljördid not inhabit the body long. He was weakly and unfitfor the hard life to which we both were subjected.Before he was seven he left us and returned to the Landof Many Temples. Yaso was six when he passed over,and I was four. I still remember when they came forhim as he lay, an empty husk, and how the Men of theDeath carried him away to be broken up and fed to thescavenger birds according to custom.Now Heir to the Family, my training was intensified.I was four years of age and a very indifferent horseman.Father was indeed a strict man and as a Prince of theChurch he saw to it that his son had stern discipline,16/347

and was an example of how others should be broughtup.In my country, the higher the rank of a boy, the moresevere his training. Some of the nobles were beginningto think that boys should have an easier time, but notfather. His attitude was: a poor boy had no hope ofcomfort later, so give him kindness and considerationwhile he was young. The higher-class boy had all richesand comforts to expect in later years, so be quite brutalwith him during boyhood and youth, so that he shouldexperience hardship and show consideration for others.This also was the official attitude of the country. Underthis system weaklings did not survive, but those whodid could survive almost anything.17/347

18/347

Tzu occupied a room on the ground floor and verynear the main gate. For years he had, as a police monk,been able to see all manner of people and now he couldnot bear to be in seclusion, away from it all. He livednear the stables in which father kept his twenty horsesand all the ponies and work animals.The grooms hated the sight of Tzu, because he wasofficious and interfered with their work. When fatherwent riding he had to have six armed men escort him.These men wore uniform, and Tzu always bustledabout them, making sure that everything about theirequipment was in order.For some reason these six men used to back theirhorses against a wall, then, as soon as my fatherappeared on his horse, they would charge forward tomeet him. I found that if I leaned out of a storeroomwindow, I could touch one of the riders as he sat on hishorse. One day, being idle, I cautiously passed a ropethrough his stout leather belt as he was fiddling with hisequipment. The two ends I looped and passed over ahook inside the window. In the bustle and talk I was notnoticed. My father appeared, and the riders surgedforward. Five of them. The sixth was pulled backwardsoff his horse, yelling that demons were gripping him.His belt broke, and in the confusion I was able to pullaway the rope and steal away undetected. It gave me19/347

much pleasure, later, to say “So you too, Ne-tuk, can'tstay on a horse!”Our days were quite hard, we were awake foreighteen hours out of the twenty-four. Tibetans believethat it is not wise to sleep at all when it is light, or thedemons of the day may come and seize one. Even verysmall babies are kept awake so that they shall notbecome demon-infested. Those who are ill also have tobe kept awake, and a monk is called in for this. No oneis spared from it, even people who are dying have to bekept conscious for as long as possible, so that they shallknow the right road to take through the border lands tothe next world.At school we had to study languages, Tibetan andChinese. Tibetan is two distinct languages, the ordinaryand the honorific. We used the ordinary when speakingto servants and those of lesser rank, and the honorific tothose of equal or superior rank. The horse of a higherrank person had to be addressed in honorific style! Ourautocratic cat, stalking across the courtyard on somemysterious business, would be addressed by a servant:“Would honourable Puss Puss deign to come and drinkthis unworthy milk?” No matter how ‘honourable PussPuss’ was addressed, she would never come until shewas ready.Our schoolroom was quite large, at one time it hadbeen used as a refectory for visiting monks, but since20/347

the new buildings were finished, that particular roomhad been made into a school for the estate. Altogetherthere were about sixty children attending. We sat crosslegged on the floor, at a table, or long bench, which wasabout eighteen inches high. We sat with our backs tothe teacher, so that we did not know when he waslooking at us. It made us work hard all the time. Paperin Tibet is hand-made and expensive, far too expensiveto waste on children. We used slates, large thin slabsabout twelve inches by fourteen inches. Our ‘pencils’were a form of hard chalk which could be picked up inthe Tsu La Hills, some twelve thousand feet higher thanLhasa, which was already twelve thousand feet abovesea-level. I used to try to get the chalks with a reddishtint, but sister Yaso was very very fond of a soft purple.We could obtain quite a number of colours: reds,yellows, blues, and greens. Some of the colours, Ibelieve, were due to the presence of metallic ores in thesoft chalk base. Whatever the cause we were glad tohave them.Arithmetic really bothered me. If seven hundred andeighty-three monks each drank fifty-two cups of tsampaper day, and each cup held five-eighths of a pint, whatsize container would be needed for a week's supply?Sister Yaso could do these things and think nothing ofit. I, well, I was not so bright.21/347

I came into my own when we did carving. That was asubject which I liked and could do reasonably well. Allprinting in Tibet is done from carved wooden plates,and so carving was considered to be quite an asset. Wechildren could not have wood to waste. The wood wasexpensive as it had to be brought all the way fromIndia. Tibetan wood was too tough and had the wrongkind of grain. We used a soft kind of soapstonematerial, which could be cut easily with a sharp knife.Sometimes we used stale yak cheese!One thing that was never forgotten was a recitationof the Laws. These we had to say as soon as we enteredthe schoolroom, and again, just before we were allowedto leave. These Laws were:Return good for good.Do not fight with gentle people.Read the Scriptures and understand them.Help your neighbours.The Law is hard on the rich to teach themunderstanding and equity.The Law is gentle with the poor to show themcompassion.Pay your debts promptly.So that there was no possibility of forgetting, theseLaws were carved on banners and fixed to the fourwalls of our schoolroom.22/347

Life was not all study and gloom though; we playedas hard as we studied. All our games were designed totoughen us and enable us to survive in hard Tibet withits extremes of temperature. At noon, in summer, thetemperature may be as high as eighty-five degreesFahrenheit, but that same summer's night it may drop toforty degrees below freezing. In winter it was oftenvery much colder than this.Archery was good fun and it did develop muscles.We used bows made of yew, imported from India, andsometimes we made crossbows from Tibetan wood. AsBuddhists we never shot at living targets. Hiddenservants would pull a long string and cause a target tobob up and down—we never knew which to expect.Most of the others could hit the target when standing onthe saddle of a galloping pony. I could never stay onthat long! Long jumps were a different matter. Thenthere was no horse to bother about. We ran as fast aswe could, carrying a fifteen-foot pole, then when ourspeed was sufficient, jumped with the aid of the pole. Iuse to say that the others stuck on a horse so long thatthey had no strength in their legs, but I, who had to usemy legs, really could vault. It was quite a good systemfor crossing streams, and very satisfying to see thosewho were trying to follow me plunge in one after theother.23/347

Stilt walking was another of my pastimes. We usedto dress up and become giants, and often we wouldhave fights on stilts—the one who fell off was the loser.Our stilts were home-made, we could not just slipround to the nearest shop and buy such things. We usedall our powers of persuasion on the Keeper of theStores—usually the Steward—so that we could obtainsuitable pieces of wood. The grain had to be just right,and there had to be freedom from knotholes. Then wehad to obtain suitable wedge-shaped pieces of footrests.As wood was too scarce to waste, we had to wait ouropportunity and ask at the most appropriate moment.The girls and young women played a form ofshuttlecock. A small piece of wood had holes made inone upper edge, and feathers were wedged in. Theshuttlecock was kept in the air by using the feet. Thegirl would lift her skirt to a suitable height to permit afree kicking and from then on would use her feet only,to touch with the hand meant that she was disqualified.An active girl would keep the thing in the air for aslong as ten minutes at a time before missing a kick.The real interest in Tibet, or at least in the district ofU, which is the home county of Lhasa, was kite flying.This could be called a national sport. We could onlyindulge in it at certain times, at certain seasons. Yearsbefore it had been discovered that if kites were flown inthe mountains, rain fell in torrents, and in those days it24/347

was thought that the Rain Gods were angry, so kiteflying was permitted only in the autumn, which in Tibetis the dry season. At certain times of the year, men willnot shout in the mountains, as the reverberation of theirvoices causes the super-saturated rain-clouds fromIndia to shed their load too quickly and cause rainfall inthe wrong place. Now, on the first day of autumn, along kite would be sent up from the roof of the Potala.Within minutes, kites of all shapes, sizes, and huesmade their appearance over Lhasa, bobbing andtwisting in the strong breeze.I love kite flying and I saw to it that my kite was oneof the first to sour upwards. We all made our own kitesusually with a bamboo framework, and almost alwayscovered with fine silk. We had no difficulty inobtaining this good quality material, it was a point ofhonour for the household that the kite should be of thefinest class. Of box form, we frequently fitted themwith a ferocious dragon head and with wings and tail.We had battles in which we tried to bring down thekites of our rivals. We stuck shards of broken glass tothe kite string, and covered part of the cord with gluepowdered with broken glass in the hope of being able tocut the strings of others and so capture the falling kite.Sometimes we used to steal out at night and send ourkite aloft with little butter-lamps inside the head andbody. Perhaps the eyes would glow red, and the body25/347

would show different colours against the dark nightsky. We particularly liked it when the huge yakcaravans were expected from the Lho-dzong district. Inour childish innocence we thought that the ignorantnatives from far distant places would not know aboutsuch ‘modern’ inventions as our kites, so we used to setout to frighten some wits into them.One device of ours was to put three different shellsinto the kite in a certain way, so that when the windblew into them, they would produce a weird wailingsound. We likened it to fire-breathing dragons shriekingin the night, and we hoped that its effect on the traderswould be salutary. We had many a delicious tinglealong our spines as we thought of these men lyingfrightened in their bedrolls as our kites bobbed above.Although I did not know it at this time, my play withkites was to stand me in very good stead in later lifewhen I actually flew in them. Now it was but a game,although an exciting one. We had one game whichcould have been quite dangerous: we made largekites—big things about seven or eight feet square andwith wings projecting from two sides. We used to laythese on level ground near a ravine where there was aparticularly strong updraught of air. We would mountour ponies with one end of the cord looped round ourwaist, and then we would gallop off as fast as ourponies would move. Up into the air jumped the kite and26/347

souring higher and higher until it met this particularupdraught. There would be a jerk and the rider wouldbe lifted straight off his pony, perhaps ten feet in the airand sink swaying slowly to earth. Some poor wretcheswere almost torn in two if they forgot to take their feetfrom the stirrups, but I, never very good on a horse,could always fall off, and to be lifted was a pleasure. Ifound, being foolishly adventurous, that if I yanked at acord at the moment of rising I would go higher, andfurther judicious yanks would enable me to prolong myflights by seconds.On one occasion I yanked most enthusiastically, thewind cooperated, and I was carried on to the flat roof ofa peasant's house upon which was stored the winterfuel.Tibetan peasants live in houses with flat roofs with asmall parapet, which retains the yak dung, which isdried and used as fuel. This particular house was ofdried mud brick instead of the more usual stone, norwas there a chimney: an aperture in the roof served todischarge smoke from the fire below. My suddenarrival at the end of a rope disturbed the fuel and as Iwas dragged across the roof, I scooped most of itthrough the hole on to the unfortunate inhabitantsbelow.I was not popular. My appearance, also through thathole, was greeted with yelps of rage and, after having27/347

one dusting from the furious householder, I wasdragged off to father for another dose of correctivemedicine. That night I lay on my face!The next day I had the unsavoury job of goingthrough the stables and collecting yak dung, which Ihad to take to the peasant's house and replace on theroof, which was quite hard work, as I was not yet sixyears of age. But everyone was satisfied except me; theother boys had a good laugh, the peasant now had twiceas much fuel, and father had demonstrated that he was astrict and just man. And I? I spent the next night on myface as well, and I was not sore with horse riding!It may be thought that all this was very hardtreatment, but Tibet has no place for weaklings. Lhasais twelve thousand feet above sea-level, and withextremes of temperature. Other districts are higher, andthe conditions even more arduous, and weaklings couldvery easily imperil others. For this reason, and notbecause of cruel intent, training was strict.At the higher altitudes people dip new-born babies inicy streams t

the bottom, left-hand of the shield are books to symbolise the talents of writer and knowledge of the author, whereas to the right-hand side of the shield, a crystal ball to symbolise the esoteric sciences. Under the shield, we can read the motto of T. Lobsang Rampa