Transcription

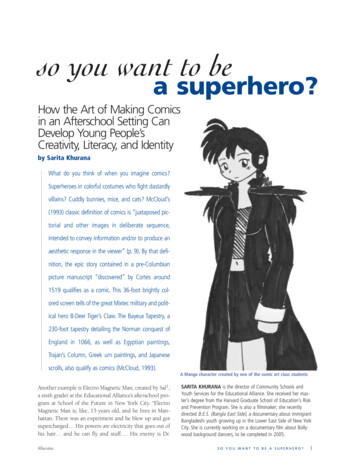

so you want to bea superhero?How the Art of Making Comicsin an Afterschool Setting CanDevelop Young People’sCreativity, Literacy, and Identityby Sarita KhuranaWhat do you think of when you imagine comics?Superheroes in colorful costumes who fight dastardlyvillains? Cuddly bunnies, mice, and cats? McCloud’s(1993) classic definition of comics is “juxtaposed pictorial and other images in deliberate sequence,intended to convey information and/or to produce anaesthetic response in the viewer” (p. 9). By that definition, the epic story contained in a pre-Columbianpicture manuscript “discovered” by Cortes around1519 qualifies as a comic. This 36-foot brightly colored screen tells of the great Mixtec military and political hero 8-Deer Tiger’s Claw. The Bayeux Tapestry, a230-foot tapestry detailing the Norman conquest ofEngland in 1066, as well as Egyptian paintings,Trajan’s Column, Greek urn paintings, and Japanesescrolls, also qualify as comics (McCloud, 1993).A Manga character created by one of the comic art class studentsAnother example is Electro Magnetic Man, created by Sal1,a sixth grader at the Educational Alliance’s afterschool program at School of the Future in New York City. “ElectroMagnetic Man is, like, 15 years old, and he lives in Manhattan. There was an experiment and he blew up and gotsupercharged His powers are electricity that goes out ofhis hair and he can fly and stuff . His enemy is Dr.KhuranaSARITA KHURANA is the director of Community Schools andYouth Services for the Educational Alliance. She received her master’s degree from the Harvard Graduate School of Education’s Riskand Prevention Program. She is also a filmmaker; she recentlydirected B.E.S. (Bangla East Side), a documentary about immigrantBangladeshi youth growing up in the Lower East Side of New YorkCity. She is currently working on a documentary film about Bollywood background dancers, to be completed in 2005.SO YOU WANT TO BE A SUPERHERO?1

Vergon Van Stratameyer who clones evilComics and theDevelopment ofmilitary geniuses like Hitler andMultiple LiteraciesNapoleon to take over the world His real name is John StrapperComic art is one of the mostand he’s like really responsiblepopular storytelling mediaand serious and but he doesn’taround the globe. From classicwant anyone to find out who heAmerican comic strips tois because it would be hard forJapanese Manga, comics coverhim” (interview, May 4, 2004).subjects ranging from humorA few months ago, in a visitous teen angst to social comto a bookstore, I went past anmentary. Youth are naturallyaisle of graphic novels, howexcited to have a chance to drawto-draw books, and comic collectheir own characters and develop theirtions. To my surprise, I saw aboutown stories in comics class. After all,ten teenagers sitting on the floor orthey’ve been reading comics for a longleaning against the bookshelves, withtime, often starting with newspapercomic strips, and they’ve been familiartheir backpacks in disarray aroundwith animated characters since theythem. Mind you, it was 3:30 in thewere introduced to Saturday morningafternoon on a beautiful spring weekday in New York City. What were allcartoons and video games. Comicsthese young people doing? They wereclass in an afterschool program is areading. This assertion may come asnatural draw for many young people.Older youth, in particular, vote witha shock to those who perpetuatetheir feet when it comes to regularthe myth that young people don’tparticipation in afterschool programs.like to read—certainly not outsideof required school reading, certainlyMany afterschool programs have natunot on a nice day when they could berally chosen to align themselves withplaying basketball or video games. Yetyouth culture, promoting activities tocomics constitute a whole genre ofwhich young people are drawn, such asreading material that fascinates manyhip-hop dance, photography, fashionyoung people.club, and soccer. To that list we can addI hear the skeptics say,I hear the skeptics say, “Well, comicscomics. As Shirley Brice Heath (2001)aren’t real reading material; those are just “Well, comics aren’t real has stated, “For some children and youthcartoons with words like ‘Pow!’ andreading material; those [afterschool programming] fosters a sense‘Wham!’ masquerading as dialogue.”of self-worth and a host of talents—parare just cartoons withSuch skeptics are missing an educationalticularly linguistic and creative—thatopportunity. At the Educational Alliance’sclassrooms neither have the time norwords like ‘Pow!’ andafterschool programs, Alex Simmons, alegal permission to foster” (p. 10).‘Wham!’ masqueradingteaching artist who specializes in comicI believe that teaching reading is bestproduction, teaches a group of fifteenlefttoschool-day teachers; however, anas dialogue.” Suchmiddle- and high-school students Theafterschool comics class can give youngskeptics are missing an people the opportunity to enhance,Art of Making Comics. In this class,comics are taken seriously both as readeducational opportunity. develop, and strengthen the skills theying material and as an art medium. Parlearn in school while engaging them inticipants learn not only the craft of comicvarious kinds of literacy work. Thoughproduction—including storyline development, charactermuch of the vast body of research on literacy instructionprofiles, sequential storytelling, and illustration—but alsohas concentrated on young children, Alvermann (2002)many of the skills that support literacy development andhas focused on effective literacy instruction for adolesidentity development in adolescents.cents. She points out that today’s society demands fluencynot only in reading, but in a multitude of areas including2Afterschool MattersSpring 2005

computer, visual, graphic,and scientific literacy.Effective literacy instruction for adolescents acknowledgesthat all uses of written language (e.g.,studying a biologytext, interpreting anonline weather map,and reading an Appalachian Trail guide)occur in specific places and times as partof broader societalpractices (e.g., formalschooling, searchingSal’s Electro Magnetic Manthe Internet, and hiking). [It] builds on elements of both formal andinformal literacies. It does so by taking into accountstudents’ interests and needs while at the same timeattending to the challenges of living in an information-based economy during a time when the bar hasbeen raised significantly for literacy achievement.(Alvermann, 2002, pp. 190–191)Alvermann specifies a number of areas that effectiveadolescent literacy instruction addresses: issues of selfefficacy; student engagement in diverse settings with a variety of texts, including textbooks, hypermedia texts, anddigital texts; the literacy demands of subject area classes,particularly for struggling readers; and participatory instructional approaches that actively engage adolescents in theirown learning (Alvermann, 2002). The art of making comicsis a viable medium for addressing several of these areas.Scott McCloud’s 1993 book Understanding Comics is afoundational text in comics theory. On the first page, hesummarizes the appeal of comics for adolescents in hisown story: “When I was a little kid I knew exactly whatcomics were. Comics were those bright, colorful magazines filled with bad art. Stupid stories and guys in tights.I read real books, naturally. I was much too old for comics.But when I was in eighth grade, a friend of mine (who wasa lot smarter than I was) convinced me to give comicsanother look and lent me his collection. Soon, I washooked!” (McCloud, 1993, p. 2).Being “hooked” is exactly how I would describe mostof the students in Alex’s comics class. In one of my first visits, I met Sal, the sixth-grade comic artist. Sal could not stoptalking about Electro Magnetic Man. “Who?” I asked, inKhuranadeep amusement andinterest. “Electro MagneticMan,” Sal repeated withserious firmness. “Oh,OK,” I said, trying to get itright, “Tell me about Electro Magnetic Man.” Andthat was the beginning ofmy immersion into theworld of youth comic production.The Background ofthe Comics ClassThe Educational Alliance,an old settlement house inthe Lower East Side of NewYork City, serves childrenand families in a number of capacities, including Head Start,afterschool, and mental health programs. My role there is tooversee the development of community schools and youthprograms. My research for this article took place at School ofthe Future, a public middle and high school in Manhattanwith which we’ve partnered for the past five years to providean afterschool program. Our partnership with School of theFuture is like several others we have with schools across NewYork City, where we support and expand the school day byproviding young people with enrichment opportunities theydo not usually get in school. I regularly work with theAlliance’s afterschool director at School of the Future tooversee the program, but during my research for this article,I participated simply as an observer of the class.Students at School of the Future are sixth to twelfthgraders from all over the city—a diverse mix of AfricanAmerican, Latino, Asian, and white students. Of the 550students enrolled in the school, approximately 300 arepart of the daily afterschool program. Most attend theprogram because they like what’s offered there: arts,technology, sports, academics, and recreation. Studentsselect their own classes each semester and receive elective school credit for regularly participating in and completing the classes. This credit helps build connectionswith the school day and provides recognition of thelearning students do after school. All our classes use project-based learning; culminating projects include performances and visual art displays.During the spring 2004 semester, the comics classhad 15 students, about two-thirds from the middleschool, and the rest from the high school. As many girlswere enrolled in the class as boys. About half of the stu-SO YOU WANT TO BE A SUPERHERO?3

Multiple Literacies in the Comics Processstripvilleretams’s HnahonWydents were new to class, while the rest were re-enrolledfor at least a second semester.The instructor, Alex Simmons, has been working inthe afterschool setting for the past four years. His background is in the comics industry; he spent many years producing and writing his own work, BlackJack, a comic aboutan African-American soldier of fortune set in Tokyo in themid-1930s. As an African-American man, he is a veteranof dealing with the difficult race and class dynamics of anindustry that has traditionally been managed by white mencatering to a white male audience. Of the many afterschooleducators/teaching artists that I know, Alex is one of thebest. He cares deeply about his students and is extremelyknowledgeable and passionate about his medium.My research took place in spring 2004. I attendedthe comics class every Wednesday afternoon for threehours during 12 weeks. I not only observed the studentsand teacher but also participated in several of the exercises during class time; in addition, I spoke with students—individually and in groups—informally as theywere working, pulling some of them aside for more formal interviews during class time. Alex and I met severaltimes outside class to speak about the class and variousstudents’ work.4Afterschool MattersA typical day in the comics class begins with a lot of chatter. Sometimes I arrive before 3 PM to find several students already in the classroom, pulling out theirsketchpads and notebooks, as the rest of the students filter in from snack downstairs in the auditorium. On oneparticular day, I notice Hillary and Wynonah, two middleschool girls, already seated next to each other, busilyupdating each other on what’s happened in their comicstories since last week’s class: Wynonah’s animal characters in “Hamsterville” have run away from home andarrived in New York City; Hillary is still working onher sketch of her main character, Gladiator Girl.Most of the students sit in twos and threes, working and talking even before Alex has officiallystarted the three-hour class. Others sit by themselves, usually wearing headphones, working intheir own musical space. Someone alwaysbrings in a new comic book to show or has astory to tell about his or her character’s latest adventure.Like any other written medium, comic book storytelling has its own conventions. Students begin by learning the basic elements of the page: panel, thought-bubble,speech balloon, caption box. Other basics are visualrather than word-based: drawing the human body, learning perspective. Ultimately, students learn how to useboth images and words to construct complex stories.Since not all students have fluid drawing skills, thefirst 15 minutes of class is usually an exercise in oneminute sketching. Two students volunteer to be models,while the rest tell them how to pose. For instance, whenWynonah and Hassan volunteered, the rest of the classcalled out action poses: “You guys have to act like Hassan is riding a horse, and Wynonah, you’re on thefloor in pain.” “OK, both of you pretend you’re doing aMatrix pose like jumping between buildings.” Then weswitched to two new volunteers: “OK, Jake, you’re dancing, and Mia, you’re sitting in a yoga pose near his feet.”“Jake, you lie down, and Mia, you stand up and pretendyou’re going to kick him in the stomach” (field notes,February 10, 2004). These exercises get students to seethe world from different angles and help them with theirdrawing styles. Students work on basic drawing techniques such as line, shape, color, and perspective. Theycan have their classmates pose in stances that occur intheir storyline, so they can practice drawing somethingthat is relevant to their work. Sometimes Alex asks thestudents to make a one-minute sketch into a comic strip,so that the drawing practice becomes an exercise insequential storytelling.Spring 2005

When sketching time is over, students get down toCharacter and Story Developmentwork on their projects. New students begin with threeComic book production begins with developing a profileor four-panel comic strips like those in newspapers.sheet for the main character: What is her motivation andEven a three-panel strip requires a storyline; it has tobackground? What are the main events in her life? Linta,have a beginning, middle, and end. Students need toanother sixth grader, shows me the profile sheet for herthink about elements of story structure: What is thecharacter, Muoliko, drawn in full Japanese Manga stylegenre—science fiction, adventure, fantasy? Who are theand personality. It reads: “Muoliko—she is turned into acharacters? What is the mood—humorous, serious, orhalf-cat for stealing and eating someone’s magic red beansuspenseful? What is the point of the story? What arecakes. She eats them and is kicked out of her house by herthe first and last shots the audience will see, and what’ssister because her younger brother is allergic to red beanin the middle? Sal’s first four-panel comic strip aboutcakes. She takes care of herself. Muoliko trys to find a wayElectro Magnetic Man introducedto undo the spell. Tomboyish, Agethe character, who is shown being11, comes from the planet Copiko”This may not seem like thezapped by telephone wires. The last(profile sheet obtained in an interpanel shows him with electric yellowview, April 28, 2004).kind of writing students havezigzag hair and a bolt of lightingNext, students write pitch sheetssimilar to the ones professional comiccoming out of his left hand,to do in English class, butannouncing, “I’m Electro Magneticartists use to present their work. Inthey are learning to use suchMan!” This may not seem like thethis storyline summary, students arekind of writing students have to donot yet working on the exact details,basic literary elements asin English class, but they are learnbut they have a good idea of the storyplot, character, and theme.ing to use such basic literary elestructure as a whole. Next comescript layouts: thumbnails of eachments as plot, character, and theme.Once students feel comfortable developing a basicpage of the comic book. This is the step in which studentscomic strip, they can move on to more elaborate work.work out the details of their story. A script layout can take aOne option is to develop their initial strip into a series.student an entire semester to produce, because it includes aAlex asks students to think of themselves as comic artistsrough sketch not only of text but also of images.producing for a daily newspaper, so that they make aTogether these pieces—character profile sheet, pitchnew comic strip for every class and complete a wholesheet, and script layout—make up a presentation package.series within a semester. Malcolm, a sixth grader new toStudents could go to an industry representative with a prothe class, is working on a series called “Fowl Prey,” infessional portfolio of their work. Once the presentationwhich a group of birds conspire to conquer the world.package is complete, students move on to actually writing,The first strip shows a group of seven or eight birdsdrawing, inking, lettering, and coloring the entire comic.meeting in the basement of a house, establishing theirpurpose: to rid the city of other gangs. By the end of theLearning Professional Standardsspring semester, Malcolm has produced eight “FowlAlex likes to intertwine the conventions of the comic bookPrey” comic strips. The birds have come a long way inindustry, which he knows from the inside, into the class.carrying out their dastardly plot—and Malcolm hasHe helps students connect with the larger world and givescome an equally long way in his ability to use the elethem room to envision themselves as professional comicments of narrative.artists. Linta, creator of Muoliko, tells me that she has beenAnother project option for students is to developinterested in Japanese comics and animation since shetheir own comic book. Newer students usually work onwatched a Hayao Miyazaki film called My Neighbor Totoro,producing a four-page comic book, while more seasonedand then Sailor Moon, when she was six. She tells me thatstudents may produce a complete 22-page comic. Theshe wants to grow up to be a Manga artist and that theprocess is the same, and Alex has a way of breaking itclass has allowed her to pursue her vocation.down into manageable chunks. Like many good afterIn comics class, young people explore all sides of theschool educators, he starts where the students are—withcomic book industry. They learn the various roles, such astheir enthusiasm and ideas. This practice of engagingpenciler, writer, inker, editor, colorist, and letterer; someyoung people’s interests, taking their skill level intotimes they practice these roles on each other’s work, in theaccount, is central to good youth development.way production is typically broken down in the industry.KhuranaSO YOU WANT TO BE A SUPERHERO?5

Students also get a sense of what the world of comics islike with trips to the Museum of Comic Art or to comicbook publication houses such as DC Comics or Marvel.Multiple Points of Entry into LiteracyStudents develop what they learn in school in new ways,putting Greek mythology or their fifth-period scienceexperiment into their comics. Of course, they also draw onpopular culture references and their own experiences.Whether they’re working from television, the latest videogame, or someone they know, ultimately the class is abouttelling stories in visual and verbal form.Engaging young people in comic production is aclever way to help them work on language arts skills. Alook at the four New York State English language arts standards reveals how comics can enhance literacy instruction:Standard 1: Students will read, write, listen andspeak for information and understanding.Standard 2: Students will read, write, listen andspeak for literary response and expression.Standard 3: Students will read, write, listen andspeak for critical analysis and evaluation.Standard 4: Students will read, write, listen andspeak for social interaction. (New York State EnglishLanguage Learning Standards, 2004)Comic book reading can serve as one of many possiblepoints of entry into literacy. When I asked Hassan howlong he’d been reading comics, he said that he’d been intocomics since he was five: “Yeah, I used to play lots of videogames and my dad wanted me to learn to read so he gaveme comic books to read like the original Batman andSuperman. That helped me be more interested in reading and give it a try” (interview, May 4, 2004).The varieties of comic books and graphic novels areas diverse as those of any literature, ranging from sciencefiction, fantasy, and adventure to teen romance and humor.One interesting phenomenon has been the introduction ofJapanese Manga. While, in the West, mainstream comicsare almost entirely for children and adolescents, in Japan,many different types of Manga are written for people of allages and both genders. It is not uncommon to see a midEach of these standards is addressed in producingdle-aged man reading Manga on the subway. Mangacomics. A comic artist must process information bycomics are taken as a serious form of literature; whilesequencing the plot of a comic before writing it, as demonAmerican comics are 22 pages long, the average Mangastrated in students’ development of a character profile sheetcomic has 350 pages and contains as many as 15 chapters.and script layouts. Comic art is an expressive, interpretiveThe introduction of Manga in the U.S. has opened up aart form with a long history of techwhole new audience for comics:niques and aesthetics; students needgirls. The comic industry in the U.S.Comic book reading can serveto work at interpreting how thehas always been geared for a whitemale audience; the vast majority of as one of many possible points images and text work together to tellthe story. In order to effectively tell acharacters are white males in someof entry into literacy.comic story, the artist must analyzesuperhero fantasy quest. However,there is a whole genre of Manga writand evaluate the underlying meaningten specifically for girls. Such Manga as Love Hina andof the story. The artist must also interact socially with otherPitaten, with their strong female leads, appeal to girls likereaders; students often discuss their work in small groups inLinta, who said she prefers “stories that have more buildthe comics class. The reading aspect of the standards is alsoup than American comics” (interview, April 28, 2004).addressed, as students further support their investment inPartly because of the popularity of Manga, at least half ofcomics by reading various publications, exploring differentthe comics class is usually female, and many of the femalegenres, and learning new vocabulary. Students often revisestudents’ characters reflect these Japanese comics.their work with the help of the instructor, going throughseveral drafts to produce the final version.Using Comic Art to SupportThe process by which Hassan, a seventh grader whoLearning Standardshas been in the comics class for two years, worked out hisComic storytelling is a rich medium with which afterstory demonstrates how comic production can promoteschool practitioners can build on the skills and knowledgeresearch and inquiry skills as well. Hassan’s comic featuresstudents learn during the school day. Alex makes regularHazara, an orphan who was raised in a monastery in 16threference to what is taught in language arts, English, socialcentury Japan. Of course the monks have trained him, sostudies, science, and history classes. He even has studentsthat now he is a super-powered Samurai warrior. Hassancame up with his character because he loves Samuraiwork up single-panel political cartoons, which give themovies. But when put to the challenge of actually figuringclass an opportunity to discuss current events and politics.6Afterschool MattersSpring 2005

out his character’s life, Hassanhad to do some research to fillin the gaps in his knowledge.Where did Samurais come from?How were they raised—in anoble family, as peasants? Howwere they trained?Other students might beattracted to a different genre, suchas sword and sorcery. Alex asksthem what they know about historyand mythology, so that they start bybuilding on their own knowledgebase. He shows them examples of howother comic artists have developedtheir settings. Then Alex helps studentsfind appropriate books and encouragesthem to use the web to look up the relevant historical period and read about theplaces they want to use as settings.On a recent visit, Sal showed me hislatest Electro Magnetic Man strip, and Iasked him to describe what was happening. “In the first panel, that’s a U.S. battleship patrolling the waters. In the secondPrey’s Fowlpanel, that’s Napoleon sailing in an old 48MalcolmmofrleA pangunner ship and it’s about to attack the U.S.ship.” “OK, wait,” I say, “How do you know so muchbecause it is their own creation. As McCloud (1993)about ships?” (I had no idea what a 48-gunner ship mightexplains, “entering the world of the cartoon, you see yourbe.) I found out that Sal is a big fan of ships, and notself through factors such as universal identification, simonly from watching Master and Commander one too manyplicity, and childlike features of characters” (p. 57). Thetimes. He told me about a collectioncartoon ”is a vacuum into which ourof books about Horatio Hornbloweridentity and awareness are pulled Comic art is an expressive,and the British Royal Navy (interan empty shell that we inhabit whichinterpretive art form with aview, May 4, 2004). Although theseenables us to travel in another realm.books are too advanced for him toWe don’t just observe the cartoon, welong history of techniques andread, his love of ships has gottenbecome it ” (McCloud, 1993, p.him into listening to the books on57). Inventing characters and storyaesthetics; students need totape. Reading them himself is cerlines is a way for young people towork at interpreting how the express feelings, play out likes andtainly in his future.images and text work together dislikes, make choices, and test newAdolescent Identityideas.to tell the story.Development throughEva’s comic, Night Shade, illusComic Arttrates how young people can useProducing comics not only supports young people’s litercomic production to work out common adolescent identityacy development, but also promotes their identity develissues. Eva, a ninth grader, is in her third year in the comicsopment. As young people grapple with questions ofclass. She has developed a complete 22-page comic bookidentity during adolescence, comics production in the afterabout Night Shade, a 16-year-old girl whose father was murschool program offers them a unique way to enter into andered by a police officer. Because the family is poor, Nightimagined world that allows them to experiment in safetyShade’s father resorts to burglary in order to care for himselfKhuranaSO YOU WANT TO BE A SUPERHERO?7

and his daughter. On one such expedition, an alarm getstripped and a police officer is called. Somehow, too muchforce is used, and Night Shade arrives on the scene to seeher father beaten to death by the police officer. Night Shadeswears to avenge her father’s death by tracking down thispolice officer. As she has no means of survival, she does whatshe knows best—she steals. Inevitably, she is caught andsent to prison. There she meets a woman scientist whopromises to give her superpowers if Night Shade will, onher release, take revenge on the assistant who gave the scientist up to the authorities. With this pact, Night Shadegains powers Eva described inan interview as “speed, strength,agility, and aim. Her secretweapon is the ability to use nightshade, a poison that she candraw from her veins and injectinto others” (interview, April 28,2004). When Night Shade getsout of prison, she goes on aquest to find first the scientist’senemy and then her father’skiller. Eva’s first full-lengthcomic ends at the point at whichNight Shade has tracked downthe scientist’s assistant and is faceto face with him in a late-nightbrawl in his laboratory.that body killed his parents. After he leaves the monastery,he becomes friends with other people, but I guess he’s looking for his purpose. He’s kind of soul-searching and dealing with this demon” (interview, May 4, 2004).The fact that the characters are in the world on theirown parallels the adolescents’ own desire to explore theirworld. Through their characters, these young people try onnew identities, playing with different subject positions.When the characters build community with new charactersthey meet, they are transforming themselves to adopt andoccupy new spaces. In this moment, the young people arefiguring themselves out and makingmeaning of their world. In creatingtheir comic characters—from thekind of personality they have to theclothes they wear, the time periodsthey occupy, and the adventures theyseek—these young artists are defining a world of their own choosing.Shirley Brice Heath writes thatyoung people’s art “layers identitiesand confuses categories of societalassignment” (Heath, 2001, p. 13).She says that young people’s artresists their usual role assignments inthe “real” world. Students’ characterscan be independent in the comicworld, making choices that may notbe available to their authors in theirSeparation andreal lives, at least not until they areEva’s character, Night ShadeTransformationadults. For young people, who areLike Night Shade, all of theusually marginalized in adult society,Throughtheircharacters,thesemain characters in these students’expressing themselves in artistic posworks are somehow in the world onsibility, in imagined and futuristic sceyoung people try on newtheir own. Whether they are cute,narios, is an attempt to defy societalmagical, or villainous animals like identities, playing with different role assignmen

foundational text in comics theory. On the first page, he summarizes the appeal of comics for adolescents in his own story: “When I was a little kid I knew exactly what comics were. Comics were those bright, colorful maga-zines filled with bad art. Stupid stories and guys in tights. I read real books, n