Transcription

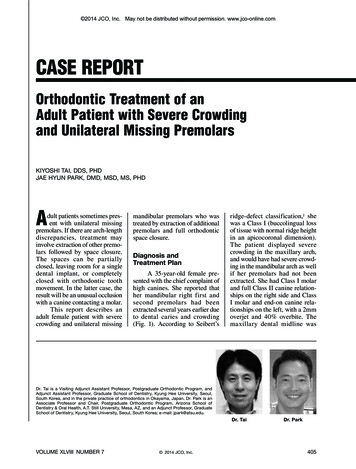

2014 JCO, Inc. May not be distributed without permission. www.jco-online.comCASE REPORTOrthodontic Treatment of anAdult Patient with Severe Crowdingand Unilateral Missing PremolarsKIYOSHI TAI, DDS, PHDJAE HYUN PARK, DMD, MSD, MS, PHDAdult patients sometimes present with unilateral missingpremolars. If there are arch-lengthdiscrepancies, treatment mayinvolve extraction of other premolars followed by space closure.The spaces can be partiallyclosed, leaving room for a singledental implant, or completelyclosed with orthodontic toothmovement. In the latter case, theresult will be an unusual occlusionwith a canine contacting a molar.This report describes anadult female patient with severecrowding and unilateral missingmandibular premolars who wastreated by extraction of additionalpremolars and full orthodonticspace closure.Diagnosis andTreatment PlanA 35-year-old female presented with the chief complaint ofhigh canines. She reported thather mandibular right first andsecond premolars had beenextracted several years earlier dueto dental caries and crowding(Fig. 1). According to Seibert’sridge-defect classification,1 shewas a Class I (buccolingual lossof tissue with normal ridge heightin an apicocoronal dimension).The patient displayed severecrowding in the maxillary arch,and would have had severe crowding in the mandibular arch as wellif her premolars had not beenextracted. She had Class I molarand full Class II canine relationships on the right side and ClassI molar and end-on canine relationships on the left, with a 2mmoverjet and 40% overbite. Themaxillary dental midline wasDr. Tai is a Visiting Adjunct Assistant Professor, Postgraduate Orthodontic Program, andAdjunct Assistant Professor, Graduate School of Dentistry, Kyung Hee University, Seoul,South Korea, and in the private practice of orthodontics in Okayama, Japan. Dr. Park is anAssociate Professor and Chair, Postgraduate Orthodontic Program, Arizona School ofDentistry & Oral Health, A.T. Still University, Mesa, AZ, and an Adjunct Professor, GraduateSchool of Dentistry, Kyung Hee University, Seoul, South Korea; e-mail: jpark@atsu.edu.Dr. TaiVOLUME XLVIII NUMBER 7 2014 JCO, Inc.Dr. Park405

Orthodontic Treatment of an Adult Patient with Severe CrowdingFig. 1 35-year-old female patient with severe crowding, deviated lowermidline, and previously extracted mandibular right first and secondpremolars.406JCO/JULY 2014

Tai and ParkTABLE 1CEPHALOMETRIC ANALYSISSNASNBANBWits appraisalSN-MPFH-MPLower facial heightU1-SNU1-NAIMPAL1-NBU1/L1Upper lipLower lipcoincident with the facial midline, but the mandibular dentalmidline was deviated by 2mm tothe right.A panoramic radiographrevealed that the patient was alsomissing her maxillary thirdmolars. Cephalometric analysis(Table 1) indicated a skeletalClass I (ANB .5 ) with a hyperdivergent growth pattern (SN-MP 37.2 ). The maxillary incisorswere slightly retroclined (U1-SN 101.9 ), but the mandibularincisors were normally inclined(IMPA 89.3 ).One treatment option was toextract the maxillary first premolars and mandibular left secondpremolar (due to its significantrestorations) and close the extraction spaces. The space of themissing mandibular right premolars would be restored with a dental implant after orthodonticVOLUME XLVIII NUMBER n82.0 80.0 2.0 1.1mm34.0 28.2 55.0%104.0 22.0 90.0 25.0 124.0 1.2mm2.0mm75.7 75.2 0.5 –4.5mm37.2 28.3 54.8%101.9 26.2 89.3 21.7 131.5 –1.1mm0.5mm75.4 74.7 0.7 –2.9mm35.4 26.5 54.6%103.0 29.6 89.5 19.7 130.0 –4.3mm–1.8mm75.1 74.7 0.4 –3.2mm36.1 27.0 54.4%102.5 28.9 87.7 18.5 132.2 –4.5mm–1.8mmtreatment. The patient declinedthis plan because she did not wantto have an implant.Another alternative was torestore the space of the mandibular right premolars by autotransplantation of the maxillary rightfirst premolar. Although the patient was willing to undergo thisprocedure, involving socket preparation 2 and a bone graft, theprognosis was not favorable dueto the atrophic extraction site andthe complete development of themaxillary first premolar.A final option was to closeall the extraction spaces, including the area of the missing mandibular right premolars, withorthodontic tooth movement.This would result in an unusualocclusion between the mandibular right canine and first molar,along with a risk of dehiscence onthe buccal side of the mandibularright first molar after mesialmovement of the tooth. Afterfully discussing the options withher general dentist, the patientagreed to this treatment plan.Treatment ProgressOnce the maxillary firstpremolars and mandibular leftsecond premolar were extracted,preadjusted .022" .028" appliances were bonded in both arches for leveling and alignment. Themaxillary arch was leveled with aseries of continuous archwires,from .014" nickel titanium to .019" .025" beta titanium (Fig. 2).After four months of leveling and alignment, two 1.6mm 9mm temporary anchorage devices* (TADs) were inserted in the*OSAS, registered trademark of DewimedMedizintechnik GmbH, Tuttlingen, Germany; www.dewimed.de.407

Orthodontic Treatment of an Adult Patient with Severe CrowdingFig. 2 After four months of leveling and alignment.interradicular bone between themaxillary second premolar andfirst molar. The bone was of sufficient quality that the TADscould be loaded immediately. An.019" .025" stainless steel archwire was then used for en masseretraction and intrusion of themaxillary anterior teeth.When the patient declinedto have TADs inserted in themandibular arch, an .017" .025"stainless steel lower archwirewith closing loops was placed,and Class II elastics were used toprotract the mandibular molarsduring space closure (Fig. 3). Tohelp open the bite, chain elasticwas attached from the TADs tocrimpable archwire hooks between the maxillary central andlateral incisors. The patient alsowore midline elastics at night tocorrect the dental midline.After 22 months of treat-408ment, the crimpable hooks weremoved between the maxillarylateral incisors and canines, andelastics were engaged to theTADs for bodily retraction of theanterior teeth (Fig. 4).Final detailing was accomplished with .016" .022" stainless steel archwires in conjunctionwith posterior up-and-down elastics and midline elastics. Totaltreatment time was 32 months(Fig. 5A).Fixed retainers were bonded from maxillary lateral incisorto lateral incisor and from mandibular canine to canine, andwraparound removable retainerswere also delivered for both arches. To prevent reopening of theextraction spaces, the mandibularleft canine and first premolar, themandibular right canine and firstmolar, and the maxillary caninesand second premolars were tiedtogether with stainless steel ligatures for six months after debonding.During orthodontic therapy,the patient required endodontictreatment of her mandibular rightthird molar. Because the endodontically treated tooth had anextensive secondary cariouslesion, the patient was informedthat she would need a future autotransplantation of the mandibularleft third molar to the right thirdmolar site.3-7Treatment ResultsAll treatment objectiveswere achieved, including Class Icanine relationships, a Class IIImolar relationship on the rightside, and a Class I molar relationship on the left, with acceptableoverbite and overjet. Facial photographs showed an improvementJCO/JULY 2014

Tai and ParkFig. 3 After another six months of space closure and anterior intrusion, using skeletal anchorage in maxillary arch and closing loops for molar protraction in mandibular arch.Fig. 4 After 22 months of treatment, showing bodily retraction of maxillary arch. Closing loops werecinched and engaged with elastic separating rings at mandibular extraction sites to enhance activation andpatient comfort.VOLUME XLVIII NUMBER 7409

Orthodontic Treatment of an Adult Patient with Severe CrowdingAABFig. 5 A. Patient after 32 months of treatment. B. Superimposition of pre- and post-treatment cephalometric tracings.410JCO/JULY 2014

Tai and ParkABFig. 6 A. Post-treatment multiplanar reconstruction images indicate dehiscences of mandibular rightcanine and first molar. B. Volume rendering shows dehiscences are insignificant compared with those ofother teeth.VOLUME XLVIII NUMBER 7411

Orthodontic Treatment of an Adult Patient with Severe CrowdingFig. 7 Patient four years after end of treatment.412JCO/JULY 2014

Tai and Parkin smile esthetics.A post-treatment panoramicradiograph confirmed the spaceclosure and acceptable root parallelism. There were no significantsigns of bone resorption, althoughthe anterior teeth did demonstratesome signs of apical root resorption. The mandibular left thirdmolar was banded during treatment, but it was not movedaggressively to reduce the chanceof root resorption, in case thetooth was needed for future autotransplantation to the contralateral third-molar position.Post-treatment cephalometric analysis and superimposition(Fig. 5B, Table 1) indicated nosignificant skeletal changes(ANB .7 ; SN-MP 35.4 ).The maxillary incisors were nownormally inclined (U1-SN 103 ), and the mandibular incisors were unchanged (IMPA 89.5 ). Cone-beam computedtomography (CBCT) showeddehiscences on the mandibularright canine and first molar, butthe amount was insignificantcompared to that of the otherregions (Fig. 6).8At the four-year follow-upexamination, the occlusion wasstable, and the treatment resultshad been maintained (Fig. 7).DiscussionA combination of severecrowding, bimaxillary dentoalveolar protrusion, and a significant midline discrepancy isdifficult to address with orthodontics alone. Premolar extractions must often be combinedwith orthognathic surgery to cor-VOLUME XLVIII NUMBER 7rect all dental and facial problems. If a patient declines thesurgical option, however, theextraction of two premolars orone premolar and a molar in thesame quadrant can create enoughspace to relieve severe crowding,retract the proclined and protrusive anterior teeth, and correctthe midline discrepancy.9 Such acase can now be treated by removing only one premolar ineach quadrant and using temporary skeletal anchorage for enmasse distalization.10,11Treatment options for a casewith unilateral missing mandibular premolars depend on the patient’s age, the developmentalstages of the adjacent teeth, andthe condition of the atrophic extraction site. Potential risks ofmolar protraction through anatrophic ridge include dehiscence,mobility, loss of attachment,ankylosis, root resorption, devitalization, and tooth morbidity.12Protraction of mandibular molarsalso causes rotation around thecenter of rotation of the entirearch, which can open the bite andproduce a posterior crossbite.12,13Since the mandibular first molaris much larger than the premolar,this movement can compromisethe integrity of the mandibularocclusion, increase the likelihoodof root dehiscence, and result insevere occlusal wear of the antagonistic maxillary premolar.14While successful molar protraction through atrophic ridges hasbeen reported,15,16 few studieshave documented orthodontic closure of two missing premolar sitesin the same quadrant. The caseshown here indicates that such anapproach may be a viable alternative to restoration with dentalimplants or bridges.In adult patients, atrophicchanges of the alveolar processesmust be carefully evaluated before moving teeth into unilateralmissing premolar spaces. Tallgrenfound that the mean reduction inmandibular anterior alveolarridge height after extractions wasabout four times the reduction inthe maxillary anterior alveolarridge.17 Carlsson and Persson alsoreported a decrease in mandibularanterior alveolar ridge heightafter the extraction of entire dentitions for denture replacement.18Tallgren and colleagues foundvertical resorption of the maxillary anterior ridge to be twice thatof the posterior region during thefirst year after extractions.19 According to these studies, 60-65%of the vertical resorption willoccur in the first year after toothextraction.Ostler and Kokich showedthat in cases with congenitallymissing mandibular second permanent molars, the alveolar ridgewidth declined by about 25% overthe three-year period followingextraction of the second deciduous molars.20 The ridge-resorption rate then diminished over thenext four years, with an additional 4% of alveolar ridge loss.The final ridge width was onlyslightly less than the width of thefirst premolar. These authors concluded that the reduction in alveolar ridge width was not correlated with the time after extraction, but that the age of the patientat the time of extraction had aweak association with the change413

Orthodontic Treatment of an Adult Patient with Severe Crowdingin alveolar ridge width.When moving a tooththrough an atrophic extractionsite, the potential for developingdehiscences and fenestrationsmust be carefully evaluated.Davies and colleagues defineddehiscence as a lack of corticalbone at the level of a dental root,at least 4mm apical to the interproximal bone margin; fenestration is a localized defect in thealveolar bone that exposes theroot surface, usually the apical ormiddle third, without involvingthe alveolar margin.21 Dehiscences are most commonly associated with the mandibularcanines and first premolars andthe maxillary canines and firstmolars, while fenestrations aremost often found on the maxillary first molars, second molars,and canines and the mandibularcanines and lateral incisors.21,22The risk of post-extraction resorption is significantly greateron the buccal than on the lingualside in both arches.23 Fenestrationsand dehiscences cannot be evaluated with conventional radiographs; in our patient, CBCT wasrequired to identify dehiscencesof the mandibular right canineand first molar, which were insignificant compared to those inother regions.Overall, our patient wasquite satisfied with her treatment.She did not require any restorations with dental implants, andher results we

Dr. Tai Dr. Park Dr. Tai is a Visiting Adjunct Assistant Professor, Postgraduate Orthodontic Program, and . her general dentist, the patient agreed to this treatment plan. Treatment Progress Once the maxillary first premolars and mandibular left second premolar were extracted, preadjusted .022" .028" appli-ances were bonded in both arch - es for leveling and alignment. The maxillary arch .